Civilization’s going to pieces,’ broke out Tom violently. ‘I’ve gotten to be a terrible pessimist about things. Have you read The Rise of the Coloured Empires by this man Goddard? Well, it’s a fine book and everyone ought to read it … This idea is that we’re Nordics. I am, and you are, and you are.. and we’ve produced all the things that go to make civilization — oh, science and art, and all that. Do you see?

The Great Gatsby, p.18

It’s not immediately obvious where Eugenics is hiding in Gatsby. And if you have only seen Baz Luhrmann’s bewilderingly lavish movie adaptation without reading the novel, it may be more elusive still. F. Scott Fitzgerald was nothing if not ambiguous about the issue, furtive even. This elusiveness also extends to Scott’s own views about ‘Eugenics’ — the idea that planned breeding and the eradication of inferior traits of non-Nordic races could produce biologically (and intellectually) perfect human beings. Scholars of literature have often choked on a surly, drunken monologue that Scott had embarked on in a letter to his friend Edmund Wilson in July 1921. Make no mistake about it, the words he uses make any attempt to defend F. Scott Fitzgerald against accusations of bigotry, a bit of a futile affair: “God damn the continent of Europe … The negroid streak creeps northward to defile the Nordic race … Raise the bars of immigration and permit only Scandinavians, Teutons, Anglo Saxons and Celts to enter … I believe at last in the White Man’s burden.” The letter had been written from the Hotel Cecil in England. Scott had arrived at the hotel after a deeply unnerving trip to Italy. It was here that he had witnessed the appalling acts of violence carried out by the fascist Blackshirt militias as they kicked-back against the results and the narrow defeat of the National Bloc. The last straw came when an American woman was physically and verbally abused on a train the couple were travelling on. Mussolini was on the rise and Scott was becoming convinced that the violent rivalries breaking out in the country would eventually see Rome suffer the same disastrous fate as Babylon. Social order was falling apart. Civilization was going to pieces. Scott did, however, qualify his rant with a few words of self-censure: “My reactions were all philistine, anti-socialistic, provincial and racially snobbish.” Had his drunken, boorish rant, perhaps punctuated by invisible ‘smilies’, been a tongue-in cheek affair, or were we beginning to see the first amorphous shapes of a disturbing inner conflict manifest themselves in his writings? To get a better grasp of the subject we have to look a little more closely at the opening sequence of the Gatsby novel.

It’s a Fine Book and Everyone Ought to Read it

To speed up the reader’s sense of discovery Gatsby uses short, punchy scenes with a high degree of entailment. It’s an approach that is a little more typical of the screenwriter and the dramatist. The fairly limited perspective offered by Nick Carraway’s first person narrative means we can’t get reliable explanations on issues that drive the novel on any regular or meaningful basis. We discover things at that the same rate as Nick discovers things, so the dialogue has to count. It is left to the reader to spot a relationship between one seemingly random statement and the one that follows — there’s a whisper and then a reveal. Scott is asking his readers to draw the dots and make the connections.

Shortly after Gatsby’s name is mentioned for the first time by Daisy (“Gatsby? What Gatsby?”) , her ‘hulk’ of a husband Tom embarks on his monologue about a book he has become quite absorbed by: The Rise of the Colored Empires. Civilization was going to pieces, Tom snarls, and the book has the science to prove it. According to its author, the whole white race was soon going to be “submerged”. It is a “fine book and everyone ought to read it,” he encourages. The mention of Gatsby’s name in the moments that follow is a shock continuation of this exchange. As we soon come to learn, the mysterious millionaire Jay Gatsby and all that he represents, subtly extends the scope and framework of Tom’s narrative, even if we don’t grasp its full significance until nearer the climax of the novel: Jay Gatsby as ‘the other’ — the demonized outsider who with his dissolute West Egg crowd is making a devastating strike against civilisation.

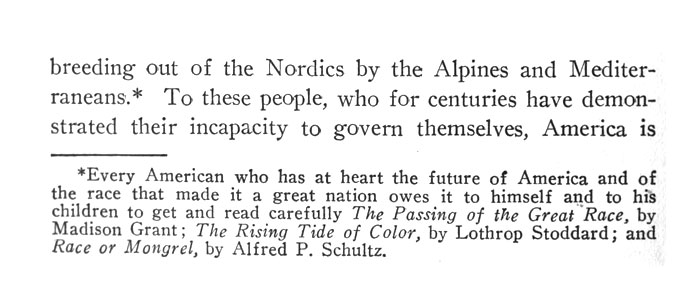

Tom’s suggestion that “everyone ought to read it” appears to have been lifted from the 1922 publication, Why Europe Leaves Home. In the book, the author had added a footnote:

“Every American who has at heart the future of America and of the race that made it a great nation owes it to himself and to his children to get and read carefully The Passing of the Great Race, by Madison Grant; The Rising Tide of Color, by Lothrop Stoddard.”

The author of the piece, Kenneth L. Roberts, was no semi-illiterate hack but a serious and respected journalist working as a foreign news correspondent for a number of leading American titles. At the time that he produced the offending article, Roberts, a former Captain with the Intelligence Section of the US Military during the Russian Civil War, had been busy producing a series of dispatches from Munich. The Saturday Evening Post had wanted a handful of snappy reports providing an eyes on the ground account of the dramatic ascent of Ludendorf and Hitler’s ‘Battle League’, then sweeping like a mania through southeast Germany. It isn’t without some irony that this casual bigot and antisemite, feted by the war office and Presidents alike, was the very first US journalist to cover the disastrous ‘Beer Hall Putsch’ led by Hitler and his party in November 1923. In his characteristically dry-witted style Roberts glimpsed both the absurdity and seriousness of the threat posed by Adolf Hitler and the Bavarian Fascisti. As ridiculous as it may have sounded to many people at that time, Roberts had seen that Germany could be united by its love of beer, and its booze-goggled romanticism. If the average German could have their Löwenbräu at low, affordable prices, a revolution could be averted. [1]

Several weeks later, Roberts would find himself under scrutiny at the Restriction of Immigrations Hearings. A new bill requesting the application of urgent emergency quotas to reduce the volume of immigrants from Asia and Eastern Europe had been tabled for discussion. Among those called to provide statements was Lothrop Stoddard who on January 7th 1924 repeated with customary zeal, the same terrifying predictions he had made in The Rising Tide of Color just two years before: unless Europe and America could get back to the state they were prior to the war, the democracy that we enjoyed in the West was going to deteriorate at an alarming rate. [2] A few weeks earlier on December 21, Congress had convened to hear the more sobering view of Gedalla Bublick, the Russian-born editor of the Jewish Daily News. The hearing’s chairman duly invited Bublick to explain to Congress how the Restriction bill they had before them was a bill of discrimination based on race prejudice. As evidence, Bublick cited the recent report of the Commissioner General of Immigration that had highlighted concerns about the continuing ‘deterioration’ of American “racial stocks”. Expanding on this, he quoted from what had become “the Bible of the Restrictionists”. The passage was taken was Kenneth L. Robert’s 1922 book, Why Europe Leaves Home. According to Bublick, Roberts had instinctively resorted to the kind of ‘Blond Supremacism’ that was popular among Eugenicists. His premise was offered in the starkest terms: ‘America’ was chiefly composed of people of the Nordic race — the tall, blond adventurous people from northern countries of Europe. Roberts was also of the opinion that the so-called Nordic race possessed certain superior physical characteristics — they had long skulls and blond hair. Not only this, they had a more sophisticated ability to govern themselves and govern others. The more recent type of immigrant — the ‘Alpines’ and ‘Mediterraneans’ — were having a having a totally negative impact on the Nordic race. The Alpines were “slow, stocky and dark” and the Mediterraneans were “small, swarthy and black haired”. In addition to these were the Hebrew race, who were not European at all, but ‘Oriental’. None of these groups, Roberts added, had ever shown success in being able to govern themselves or anybody else for that matter. [3] The book sent shockwaves across America, receiving reviews in everything from the Washington Post to the New York Times, the New York Tribune, The New York Sun and the New York Herald. As the shockwaves continued to spread, Scott Fitzgerald sat down to write Gatsby.

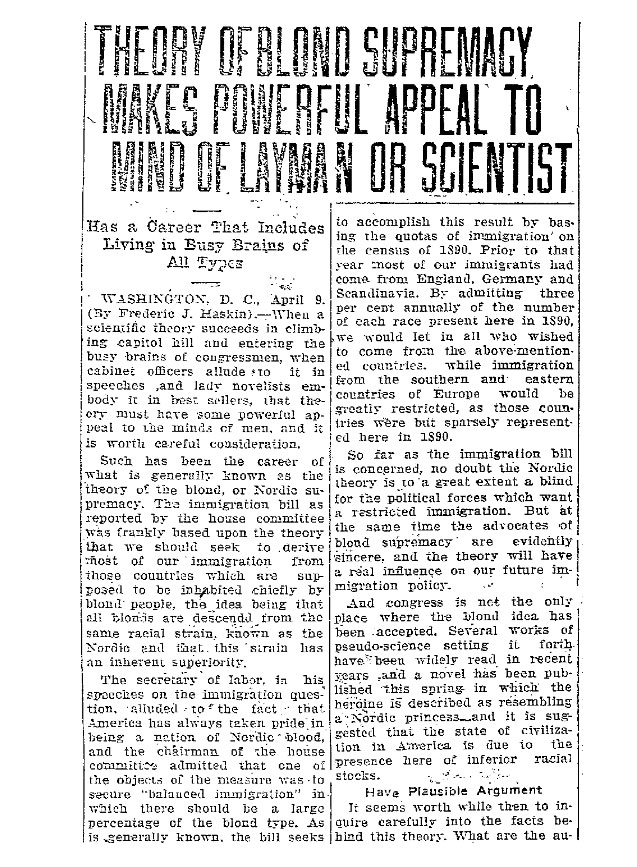

Roberts was backed-up in his findings by the US Secretary of Labour, who had seized upon the opportunity to make them central to a case for restricting foreign labour. One man who was quick to pick up on this was newspaper man and author, Frederic J. Haskin who contended that theories of ‘Blond Supremacy’ were now more appealing than ever to the men of Capitol Hill. The rowdy screams and hollerin’ of the Restriction of Immigration Bill that were now shaking the windows and the doors of congress were based upon the theory that Americans should seek to derive most of its immigration from countries chiefly inhabited by blond people — known among Eugenicists at this time as ‘Nordics’. Writing from his desk in Washington D.C, Haskin went on to describe how the Welsh-born Secretary of Labour, James J. Davis had been alluding to the fact that America had always taken pride in being a nation of Nordic blood. The chairman of the House Committee sitting in Congress in December 1923 had even admitted that one of the objects of the bill had been to secure ‘balanced immigration’, in which there should be a greater percentage of ‘blond types’. [4] The wave of mass strikes breaking out in America and Great Britain in the immediate aftermath of the war had been fuelled, at least in part, by perceptions about immigration. For men like Davis, the way to deal with the striking workers, was to deal with the ‘rising tide’ of immigrants. Haskin’s fear was that the pseudo-science of ‘Blond Supremacy’ being seized upon by Congress to settle a broad spectrum of domestic problems was going to have a far-reaching influence on the nation as a whole. The doctrine was even beginning to enter the mainstream.

Blond Supremacy

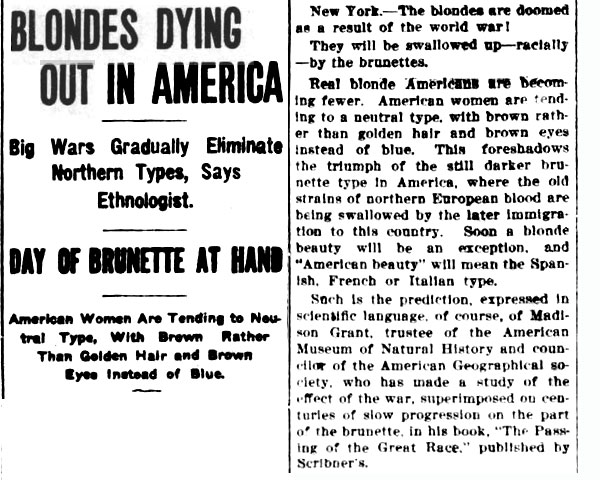

The year that Congress convened for Immigration Restriction hearings, a bestselling novel had been published in which the heroine is described as a ‘Nordic Princess’ by one of its characters. The novel was Black Oxen by Californian novelist, anti-communist and white supremacist, Gertrude Atherton. The book told the story of a tired old woman whose youth is miraculously restored after undergoing hormone treatment. It was to prove a powerful and attractive metaphor for national restoration. [5] The novel may in actual fact have been partly inspired by Fitzgerald’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, published the previous year, the story of a man who ages backwards. Described as subtle science fiction, the novel featured several Fitzgerald staples, including the swarthy-skinned anti-hero and the decadent, exuberant flapper. Atherton was of the opinion that novelists like Scott’s friend, John Dos Passos, were rapidly diluting the strong, Nordic stock of American literature. Her views of the flapper were just as uncompromising: “First let us correct physical slackness and restore thereby some measure of self-respect and mental health. The flapper in the modern corset would cease to be a flapper. She would be compelled to walk and sit with a straight spine.” [6] The moral rejuvenation of America could be accomplished, Atherton went on, by “a return to the simplicity and power” of its Nordic ancestors. Atherton’s views were dutifully buoyed-up by a regular flow of articles mourning the loss of the traditionally blond American beauty: blondes were dying out fast in America. Madison Grant, whose findings would be recycled by Roberts in his own book, Why Europe Leaves Home, believed that a large part of the breeding stock of the blond races had been destroyed by the war in Europe and increasing immigration from the Mediterranean basin and the Balkans — a region that was thought to be producing a disproportionate number of anarchists. According to Frederick Adams Wood, a Professor of Biology in Massachusetts, there had been little or no anarchistic leanings in the Nordic race. The Aryan temperament was “by nature averse to Bolshevism”.[7]

In his 2014 book, F. Scott Fitzgerald at Work, Professor Horst Kruse comments on a passage from This Side of Paradise which features a conversation between the novel’s hero Amory Blaine and his charismatic and confident friend, Burne Holiday. The pair are discussing the relevance of hair colouring to personality types. Amory has been looking over the Princeton year books of the past ten years and notices that a sizeable number of students who sat on its Senior Council were blond. Burne replies that “it’s true … the light-haired man is a higher type, generally speaking”. He adds that he has worked-out that over half of the men who had served as American President had likewise been light-haired. [8] Burne’s views had echoed by Lothrop Stoddard, whose fantastically popular, The Rising Tide of Color had provided a more robust and ‘scientific’ defence of the “big blond Nordics” — the “higher-type of man”. [9] That blonds could be found around Syria, Western Asia, and even among some Eskimos, was very casually breezed-over.

In her review of Scott’s time at Princeton, Ann Margaret Daniel attributes Scott’s familiarity with the Blond Supremacy narrative to lectures that Scott may have attended during his years at University. [10] One prominent member of its staff was Professor of Zoology, Edwin Conklin, a leading Eugenicist. The greater likelihood, however, is that the whole issue about Blond Supremacy had entered the author’s airspace from discussions about the ‘Prussian Junker’ that had been popular during wartime. These discussions about the Junker, routinely referred to as the ‘Blond Beast’ by members of the press, elegantly extended the narrative of the German race toward global supremacy. The phrase had actually taken root in the popular consciousness some years before in a less pejorative sense, as various white supremacists first looked to the writings of the philosopher Frederic Nietzsche to shore-up an Aryan narrative. In a report entitled, A Negro View of the Presidential Candidates, Colorado’s Quincy Daily Journal explained how Woodrow Wilson seemed poised to monopolise the black vote and was unlikely to push ‘blond’ interests of the State. The newspaper’s outlook was bleak: there were some several hundred millions of Chinese, Jews and Negroes “to be reckoned with”, indefinitely postponing “the date at which the blond beast will inherit the earth”. [11] By the time that Scott sat down to write This Side of Paradise, he was already familiar with Nietzsche. Philip McGowan at Queens University Belfast has already looked at this, noting both the subheading, The Superman Grows Careless in the chapter, The Egotist Considers, as well as several casual references to Nietzsche that the author makes in relation to George Bernard Shaw in the novel. [12]

The Blond Beast — from Great White Hope to Great White Villain

Nietzsche’s phrase ‘the Blond Beast’, was the continuation of an idea that had first appeared in his 1883 work, Thus Spake Zarathustra. The phrase had featured in what is now a fairly lionized passage of On the Genealogy of Morality, published some four years later. The ‘Blond Beast’ was a warrior of a ‘higher type’. According to Nietzsche, the Superman was a ‘super-beast’ who would come to destroy the current idiotic order of things in a cruel, pitiless fashion. The notion of ‘the beast’ had its roots in the races of Northern Europe, an Aryan race of Celts, who Nietzsche believed to be of superior birth both physically and intellectually. The Blond Beast, “prowling around for spoil and victory”, was a natural predator and, more crucially for Blond America, a natural winner. He would show no mercy. The sheer brutal power is why the Prussian militarists came to like it, and why the British and the Americans did everything in their power to present the Prussians as dangerous. [13]

Prior to the war, the powerful characteristics of the ‘Blond Beast’ had played to the benefit of the White Supremacists, but during the war the notion would be rather cleverly redrawn to provide a natural and persuasive bogeyman figure. Almost overnight Nietzsche’s symbol of raw, human potential became the cruel and pitiless predator that was the Prussian Junker. In just a matter of two short years ‘the Blond Beast’ was transformed from our great white hope into a great white supervillain. It was something that everybody was talking about without really ever knowing for certain what any of it actually meant or where it came from. That was the thing about Eugenics, it was a flexible, amorphous creature that could pretty well adapt to whatever fear or resentment you happened to be feeling at any time.

The socialist union of collective egoists known as the Wobblies (the Industrial Workers of the World) had been quick to notice this paradox at the very start of the war in Europe. In a report published in its vanguard newspaper, The Voice of the People in October 1914, this land-loving worker’s union had narrowed-in on an emerging paradox. On the one hand, America’s eminent Darwinian scientists were providing a forceful case for doctrine of Nietzsche’s ‘might is right’ philosophy (as well as offering proof that the perseverance of the “blond beast” was critical to man’s survival). They were doing this, they said, at the same time the world’s ‘blond beasts’ were destroying each other in Europe. [14] The irony, for the anarchists, couldn’t have been any sweeter or more desirable: the so-called Blond Beasts were doing a better job than anyone in removing their kind from the gene pool. Thankfully for the Wobblies, the war wasn’t Eugenic, it was Dysgenic. The noble Nordic bloodlines of Europe and Eurasia were to all intents and purposes committing ethnic suicide.

Just as Scott’s Newman School mentor, Father Sigourney Fay was putting the finishing touches to his own fierce diatribe on the threat of the Prussian Junker (The Genesis of the Super-Man, Dublin Review, April 1918) the publishing world provided the allies with reinforcements from the worlds of both fiction and non-fiction. First there was the little book of German Atrocities by Congregational Minister and President of the Race Betterment Foundation, Newell Dwight Hillis — an investigation and analysis of the ‘Blond Beast’, as well as a chronicle of its heinous deeds — and secondly, the book’ more romantic, novelised counterpart, The Blond Beast. The novel, written by Robert Ames Bennett, told the thrilling, boys-own story of a plucky American youth taking on Prussia’s “ruthless, ferocious and lustful” Superman equipped with little more in his kitbag than his own ‘outstanding Americanism’. [15] Did it dawn on people to ask how a man like Hillis could be extorting the virtues of the superior Nordic Race whilst at the same time taking aim at Nietzsche’s flaxen-haired Prussian Superman? Unsurprisingly, it didn’t. In fact, such was the scale of the author’s hypocrisy that when the war with Germany finished, Hillis was among the tiny fraction of Americans demanding the sterilisation of all ten million German soldiers and their women for the atrocities committed during the war. The only exception he was willing to accept to this rule was Goethe, who was not only dead already, but whose warnings about the Prussians had been completely and utterly justified. In the end, American pro-War Eugenicists like Hillis had a very simple way of handling the paradox of the war the Aryan ‘super race’: he started ditching his earlier references to the “genius of the German people” and the “excellent quality of German economic and political institutions” he had celebrated previously and replaced them with the more nebulous, evasive term ‘Nordic’. [16]

Blond Ambition in the Gatsby Novel

None of this would warrant much in the way of scrutiny if it wasn’t for the fact that the author of The Great Gatsby draws so much attention to the more conventional Aryan traits in the descriptions of several of its leading characters. First there’s Tom Buchanan, the muscular, mouthy bigot who in the very first pages of the novel tries to push The Rise of the Coloured Empires on the newly arrived Nick. Nick describes him as a sturdy “straw-haired” man whose two shining arrogant eyes only added to his dominance. Beneath his riding clothes there was a “great pack of muscle” rippling beneath them. It was“ a body capable of enormous leverage — a cruel body”. His first words to Nick, spoken as they are in jest, reveal the extent of that superiority: “Don’t think my opinion on these matters is final … just because I’m stronger and more of a man than you are”. Tom is being presented as the paternal master race, whilst Nick, and everyone else in the novel who occupies the same middle-ranking status as Nick, are being presented as the slave race. This powerful “national figure”, enormously wealthy and enormously successful, certainly has more in common with contemporary allusions to the ‘Blond Beast’ of the Prussian Junker than Gatsby, whose physical attributes, unlike practically everyone else in the novel, are mysteriously left out by the author. The only things we know for sure about Gatsby are that he has a certain elegance, a certain roughness, is aged a little over thirty, isn’t particularly tall, isn’t particularly small and has a slightly Mediterranean ‘tanned’ appearance. Physically at least, there’s little reason to suspect that Gatsby is anything like the boorish, strutting beast that is the masterful, Tom Buchanan. Whilst Fitzgerald is deliberately vague about Gatsby’s actual heritage (not least to preserve that ‘man of mystery’ appeal) he does leave a clue. Meeting Gatsby for the first time at the party, Nick remarks that based upon information he has learned from Jordan and other guests — and perhaps on account of his ‘tanned skin’ — he would have “accepted without question that Jay Gatsby had sprung from the “swamps of Louisiana or from the Lower East Side of New York” — the implication being, of course, that Gatsby could very well have passed for an immigrant.

To the Eugenicists, the greatest threat posed to Blond America was from Latin Mediterranean and Negro blood: effectively anyone of swarthy appearance whose commitment to assimilation was less than total. The issue for patriotic ‘white America’ wasn’t just about the colour of your skin, or the quality of your genes but just how prepared an immigrant was to leave their home religions, languages and histories behind and embrace the whole idea of being American. At the time that Fitzgerald was writing the novel, the Lower East Side of New York was dominated by Eastern Europeans, primarily the Jews of Poland, Belarus, Russia, Latvia and Ukraine. The ‘swamps of Louisiana’, on the other hand, were dominated by the Cajun/Acadian French, the Africans and the Spaniards — a distinctive creole race proudly resistant to Americanisation. A news report from April 1923 highlights the impervious nature of the Cajun culture. Written just as the Secretary of Labor, James J. Davis prepared his exclusion bill for Congress and Frederic J. Haskin, explained how the “vanishing Cajun clan” had recently staged a comeback rarely equalled by any of the “older American stocks”. Within the last thirty years the Cajun” had come out of the forest almost primeval of Southern Louisiana”, proving himself to be “an economic marvel who could give his Nordic brother cards and spades and beat him nine times out of ten”. Such was the scale of surprise among some American ethnologists that some were beginning to ask if the Cajun was really Nordic. [17]

Fitzgerald biographer, Andre Le Vot has made much of the incidence of colour in the novel, specifically yellow and blue, instantly recognisable as the colours of the Aryan Race — blond (yellow) hair and blue eyes. In the novel, the colour yellow, with the probable exception of a few random images, appears to represent everything that is powerful and fertile. Tom’s hair is yellow (‘straw haired’), Gatsby’s car is yellow, his tie is yellow, his Station Wagon is yellow, the frames on Dr. T.J Eckleburg’s spectacles are yellow (his eyes are blue), Jordan’s hair is yellow, Daisy’s hair is ‘yellowy’ [18], the hair colour of Daisy and Tom’s child’s Pamela is yellow, the building in which garage owner George Wilson and his wife Myrtle live is yellow, Wilson’s hair is blond (his eyes are light blue), and the eager-to-please lodger who plays piano for Gatsby, Mr Klipspringer, well even he too is described as blond. It’s as if the author of Gatsby had set about first establishing and then destroying the absurd racial premise upon which Eugenics was based: the all-powerful Tom Buchanan is graced with Aryan characteristics, but then so too is the “spiritless and anaemic” George Wilson, who may or may not represent the perceived deterioration or dysgenics of the Aryan American stock.

In 1916 Katherine M. H. Blackford, a self-styled authority on physiognomy and character analysis, had published Blondes and Brunets. In the book she noted that until very recently, “most dolls had blue eyes and yellow hair, even in countries where their mothers were as brown as berries”. Blackford went on to provide an exhaustive and heavily mythologised account of the development (and disappearance) of the Aryan race, a story which drew substantially on The Origin of the Aryans (1890), a less opinionated ‘yellow hair’ guide by toponymist and radical priest, Isaac Taylor. None of what Blackford was saying was new. As America looked to introducing the first of its more comprehensive immigrant restriction laws in 1891, some sections of the country’s press were sharing their concerns that the ‘yellow haired’ Aryan race who once ruled Europe were a dying breed. All the best people had yellow hair, they gloated, even the Greek Gods. Now, the greatness was fading and the Gods were no longer what they were in the past. [19] But not everyone looked upon the blond-haired race so favourably. G.K. Chesterton’s The Appetite of Tyranny, published in 1915, takes an entertaining and often amusing swipe at the pompous personality traits that to war-time imaginations epitomized the Prussian Race: “I see nothing outside, except a sort of smiling, straw-haired commercial traveller with a notebook open, who says, “Excuse me, I am a faultless being … What place is there on earth where the name of Prussia is not the signal for hopeful prayers and joyful dances?” [20]

The novel’s narrator, Nick Carraway fails to add much in the way of commentary on these issues, and as a result it is really very difficult to say with any certainty which, if any, viewpoint the narrator or author is taking — whether Scott, like Stoddard and Grant, laments the loss of yellow hair or like Chesterton finds it all dryly amusing. Either way, it is probably fair to say that in Scott’s eyes at least, Tom Buchanan may have represented the ‘Gold Standard’ of the Nordic Race, and poor old George Wilson, the pitiful, degraded ruin that some thought it risked becoming — or in Lothrop Stoddard and Madison Grant’s eyes, the ruin it had become already.

Professor Kruse suggests that the playful reference to Goddard in the novel may not be play on the name Stoddard at all, but a much less ambiguous reference to psychologist, Henry H. Goddard, whose 1911 book, the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness had made a considerable splash at the Eugenics Record Office of New York. In all fairness I think it probably an even more playful and irreverent conflation of both. Like most men and women his age, Scott would have derived much of his knowledge from the more sensational headlines and non-fiction of the 1922-1924 period when Secretary of Labor, James J. Davis had been aggressively campaigning on the Restriction of Immigrants issue, a bill on ‘selective immigration’ that had been introduced by Eugenicist, Albert Johnson of the House Immigration Committee and Senator David Reed in April 1923. As the Harding administration grappled with concerns about labour shortages, Ku Klux Klan favourites like Johnson — closely aligned with the Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor — frantically fought off efforts to relax the current immigration laws.

In all fairness, Scott’s contact with the ideology of White Supremacy was more likely to have come from reading the news columns and attending parties where discussion about these things was full of woozy, half-grasped notions and compellingly fashionable half-truths. Perhaps, as a result of either of Scott’s ignorance or dark humour, the soundalike names of Henry H. Goddard and Lothrop Stoddard had become confused (or even juxtaposed) in some way. If true, then Tom Buchanan’s ‘Goddard’ is not any one person, but a convenient composite archetype, inherited from the kinds of heated discussions taking place at that time — arriving on the fly from part of a brutal collective consciousness and the common confabulations of a dying old class under threat. Because Tom Buchanan’s Rise of the Colored Empires more closely resembles Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color (published to global acclaim just the year before by Scott’s own publisher, Scribner’s) and in light of the fact that Kenneth L. Roberts was recommending that every American should read it at the time that Scott was writing Gatsby, I am more inclined to think that the author’s reference to a man called ‘Goddard’ has a more generous measure of Lothrop Stoddard than Henry H. Goddard about it, despite the actual repetition of the name. You only have to looking at the language that Tom is using. Expressions like ‘civilisation’ and ‘dominant race’ are far more characteristic of the later (and infinitely more ideological) master race narratives of men like Grant and Stoddard than they are of the more blandly academic, Henry H. Goddard. Goddard doesn’t talk of anything quite so lofty as ‘civilisation’ in his work. Neither does he discuss the sanctity of marriage or the preservation of a ‘dominant race’. Extremist ideas like these are far more characteristic of Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race (1916), Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color (1921) and his follow-up book, The Revolt Against Civilisation (1922). In the latter two books, the belligerent pseudo-scientist very skilfully combines the issue of Dysgenics with the ‘Rebellion of the Under-Man’ — the threat posed by the Russian Bolsheviks to the very foundations of the modern civilised world. All three books were, incidentally, edited by Scott’s own editor, Maxwell Perkins and published by Scribner’s.

The Last Barrier of Civilization

As the novel reaches its climax, Scott reveals the full extent of Tom Buchanan’s vitriol: “Flushed with his impassioned gibberish, [Tom] saw himself standing alone on the last barrier of civilization.” [21] As he angrily narrows in on the threat being posed by Jay Gatsby, the objections that Tom raises are not confined to race issues but to ideological ones. Tom feels that Jay Gatsby is sneering at ‘family life and family institutions’. He’s a troublemaker. A Bolshevik. Nick observes that Tom sees himself as standing alone “on the last barrier of civilisation”. The phrase the author uses had its roots in a statement made by US Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker in January 1920 about America’s support for Poland after the Second Revolution in Russia. Baker had been responding to criticism of the Palmer Raids, in which New York Police and Federal officials had made a series of sweeping arrests on the city’s Lower East Side, as part of the nation’s hysterical response to the domestic Bolshevik threat. The raids had been seen as proof that it was now the duty of America to defend democracy abroad. Poland they said, would be the “last barrier of civilization” in Western Europe. [22] The country would be the bulwark of Christianity, a buttress against the barbarism of the East, the military threat of Germany and the spread of Lenin’s Bolshevism. [23] The military supplies and food relief for Poland being organised by Herbert Hoover and the ARA wasn’t just a humanitarian imperative, it was an ideological one.

From the narrator’s point of view in Gatsby, Tom was standing at the Gates of Vienna, pushing back the heathen hordes. Everything that White America had taken for granted was under threat: marriage, industry, the church, blond hair follicles — even the Thanksgiving turkey. This wasn’t just a fight to save Western Civilization but all civilisation. Scott had first addressed the issue in his May Day story for the Smart Set in July 1920 but if The Great Gatsby is anything to go by, he clearly had more to say. In all fairness it could well be a sad coincidence that Jay Gatsby is killed within 48 hours of America’s Labour Day weekend. However, there may be something a little more subliminal at work here too. The Restriction of Immigration Bill backed by US Secretary of Labour, James J. Davis had been rooted in attempts by his department to placate the white workers of America. Davis was determined to given them the security and assurances they felt they lacked. Despite the sad, overwhelming impact that the passing of the Bill would have on immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, it is abundantly clear that the bill had been conceived to stave off future strikes — a federal policy to protect American-born workers from cheap foreign labour. Look at it another way; Gatsby is killed by a low-paid blue-collar worker who has been bamboozled into thinking that Gatsby is to blame for the loss of his dream. It is Tom Buchanan who talks Wilson into thinking that it was Gatsby who was driving the car that killed his wife Myrtle, and taking with her any hopes that the poor young garage mechanic may have had of one day escaping the Valley of Ashes. At a figurative level at least, Jay Gatsby became the scapegoat of America’s increasingly ‘dysgenic’ workers being goaded into action by its panic-stricken over-class.

As Nick and Daisy’s friend, Jordan Baker, contends with Tom’s continuing attacks on Gatsby and ‘coloured empires’, she shares some interesting observations. The first is when she says with a heavy dose of sarcasm that Tom should “live in California” (a reference to either its long standing sterilization laws or the status the State was acquiring as the capital of Eugenics) and the second when she mutters beneath her breath that “we’re all white here” during his crisis-point rant in Chapter Seven of the novel. Tom has just accused Gatsby of sneering at family life and undermining its authority as a civil institution. Civilization was falling apart. Tom adds that before we know it, the people responsible for its fall would also be advocating inter marriage “between the blacks and whites”. Is Tom suggesting that Gatsby is not white, as some modern critics have suggested? It’s hard to tell. Tom could certainly be insinuating that he has his doubts about the full, true nature of Jay’s ethnicity, but it’s more likely that Tom is simply lumping him in with the ‘disturbing’ progressive views of some left-wing American ‘Moderns’. In the early 1920s, the Moderns were perceived to be seeking full social equality for African Americans. Behind the Moderns were Harlem’s resurgent, New Negro Movement. The subject of interracial marriage had suddenly become a ‘terrifying’ spectre. To make matters worse, Dr Manuel de Oliveira Lima, a respected diplomat and historian, had made a controversial address at the Institute of Politics in Williamstown, Massachusetts. During the course of the address, Lima argued that marriage between White and African Americans could be the most natural solution to the country’s race problems. If America followed the example of Brazil, where race was not an issue, the negro bloodline would eventually be absorbed into the white race. This, the Doctor argued, presented a far more humane solution that separation or segregation. [24] The whole thing would reach critical mass in April 1924, when New York’s Boni & Liveright would publish a novel by Jessie Redmon Fausset of the Harlem Renaissance, in which the talented young black author, writes in support of inter-marriage and the liberated week-long parties of the wealthy and ‘educated negro’. [25] Whatever Fitzgerald was driving at, it is clear that Jordan’s interjection (“we’re all white here”) as Tom finally confronts Gatsby in the hot parlour suite of the Plaza Hotel, not only underlines the absurd logic that Tom is using, it also serves to remind us that Gatsby is not, whatever he is, an African American. I think it is one of the few things that Scott doesn’t want us to misconstrue. Even if we don’t know what he is, Gatsby is not black.

As the group convene in their room at the Plaza, the band in the lounge below strike up the first bars of Mendelssohn’s Wedding March from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In the cool romantic calm of Gatsby’s house it is the “unreality of reality” that dominates. In the sizzling parlour suite of the Plaza Hotel is the reality of unreality that controls the mood. The stifling heat of the afternoon sees heart-rates rise and all manner of crazy things being said. The swirl of rumours surrounding Gatsby’s business activities condense into a seething red mist and the accusations flow. “There was no escape from the madness of four o’clock writes,” writes Scott in Absolution, the novel’s intended prologue. It is four o’clock again. Someone opens the window and the stifling hot reality of the world outside invades the fairytale room. As it does, Tom’s quips become increasingly erratic and illogical. An analogy is being drawn between the irrational fears of the post-war period and the ‘summer madness’ that stokes Tom’s fury. America’s 25th President William McKinley had been shot a little after four o’clock by anarchist Leon Czolgosz during a similarly stifling day in September 1901. Perhaps some vague memories of the event had stayed with Scott from childhood. Like the climactic scene in Gatsby all the action had taken place around the time of Labour Day in the last few days of summer. As if to compound national grief, McKinley had been gunned down by his wild-eyed assassin in the enchanted theatre of dreams that was the World’s Fair in Buffalo — the pinnacle of American Genius and innovation at that time. A five-year old Scott Fitzgerald had visited the Exposition with his family just a few weeks earlier. On that hot summer day in September it must have seemed like the dream itself was being destroyed. This too would have seemed liked madness.

If the whole episode at the Plaza Hotel seems garbled then it is because the attitudes of men like Tom Buchanan were garbled. In his soapbox address about marriage and civilisation, Tom is confusing the Bolsheviks with the Anarchists. This was a common misconception during the Red Scare of the 1920s. The Bolsheviks didn’t outlaw marriage, they secularised it. From 1918 all Soviet marriages would be civil marriages. Unlike Anarchism, Communism didn’t specifically object to marriage, or promote the cult of ‘Free Love’. The misattribution was used to scare people. It was propaganda. ‘Civilisation is going to pieces’, says Tom. ‘Mr Nobody from Nowhere’ (says Tom, looking at Jay Gatsby) is the newly subversive ‘under-man’ causing revolutionary unrest in his family home. Encouraged by “this man Goddard”, Tom Buchanan has become utterly convinced that members of the social underclass were “now busily fanning the smouldering fires of chaos” in America, spreading cynicism and scandals, “creating disbelief in everything and an eagerness for something better”. [26] This was the kind of ‘impassioned gibberish’ that Lothrop Stoddard was publishing too. Tom is presented as “standing alone as the last barrier of civilisation”. The abusive, angry bombast that characterises Tom Buchanan is completely absent in the works of Henry H. Goddard. Henry H. Goddard was, by contrast, too concerned with the specifics of intelligence testing and data-mining to be trotting out the kind of headline-grabbing soundbite recycled by Tom.

Three Modish Negroes

There are several dreamlike sequences in the novel but there are few more disorientating than the one in which Gatsby and Nick pass over Queensboro Bridge on their way to meet Meyer Wolfshiem for lunch. Again its packed with symbolism. The book’s narrator describes a passing hearse. It’s a funeral procession. Behind it trail the carriages of family and friends. As Gatsby’s flashy yellow car roars by, it catches the attention of the mourners and they peer out of the car’s windows. Nick notices that the people have the “tragic eyes and short upper lips of South Eastern Europe” — the area of Europe that was currently being addressed in the Restriction of Immigrants Bill. These would be the people of countries like Bosnia, Croatia, Romania and Ukraine. Nick has just reminded us that passing over Queensboro Bridge reveals the city as it might have looked to those who arrived here for the first time: full of beauty and “wild promise”. The city’s skyscape is described like something from a children’s fantasy: the skyscrapers that he sees rising up from the Hudson Rover are like ‘white heaps’ and ‘sugar lumps’. New York has been built from a mesmerizing fusion of honest, well-earned money and the most precious and ephemeral of “wishes”. It’s a fairy tale world where anything can happen: a city of dreams. Scott isn’t saying anything complicated here. As obstruse as it is, the point he is making is a simple one: the city was a dream for Gatsby, just as it once was a dream for those people too. The next car they see is occupied by “three modish Negros” — two boys and a girl — and they are being driven by a ‘white chauffeur’. These are the newly wealthy Black Americans we mentioned earlier, the ones that were being celebrated by Jessie Redmon Fauset in her 1924 novel, There is Confusion, the story of the Harlem Renaissance. The early to mid 1920s were the so-called golden age of black business when an increasing number of African Americans were quietly achieving millionaire status — even racketeer Harlem ‘madams’ like Stephanie St. Clair. Curiously enough, the whole car-racing episode takes place as Gatsby, Nick and the “three modish negroes” pass over Blackwell’s Island. The island — a thin strip of land between Queens and Manhattan — had long been associated with newly arrived immigrants judged to be insane and whose blighted physiognomies would be logged and scrutinized by the Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbour.

The lexicon of the late 19th century and early 20th century had a phrase for people like Gatsby. The three white Fusionist officials seized by White Supremacists shortly after the Wilmington Massacres in 1898 were insultingly branded ‘white niggers’ by the baying crowd. [27] The phrase was also applied to everyone from Italian and Irish immigrants to Roman Catholics. Let’s not beat around the bush here: Scott is leaving us in absolutely no doubt that Gatsby is viewed by Tom, and probably most of Tom’s friends, as another ‘White Nigger’ — a representative of the undesirable underclass rising like a “tide” across America. Gatsby’s conspicuous looking car is part of this alternative current flowing around New York. As gaudy and ill-gotten as it is, the car fits in neatly with the funeral cortege of Southern Eastern Europe immigrants and the limousine that is occupied by three fabulously wealthy African Americans.

Of course, what we all want to know is where F. Scott Fitzgerald stood on any of this? Did Scott share the view that America was under threat from a ‘rising tide’ of immigrants? First we need to clear about one thing: if it had been trusted observer Nick expressing the bigoted views of characters in the novel, things may been a little different, but the views are being expressed by Tom, the burly and uneducated ‘cyclops’ figure that Scott encourages his reader to loathe with every insult that he hurls and every boastful remark that he makes. That the book’s narrator dismisses Tom’s boorish rants as ‘impassioned gibberish’ may suggest the author had recognised the absurdity of the sentiments — if not in himself, then certainly in other people. Scott possessed voracious reading habits. There was unlikely to be a topic in modern America he didn’t want to be thought unschooled about: Eugenics was probably one of them. And like most men and women of his age, its likely he would have been excited by the science even if a little sceptical about its application. The evidence, such as there is in the novel, would appear to suggest that Fitzgerald is not sympathizing with these views, but acknowledging the role they play in the social mechanics of New York City at that time. These were the invisible barriers that kept poor boys like Jay Gatsby (and Scott Fitzgerald) from rising above the flood gates.

Jewish Stereotypes

The vague allusions made about Gatsby’s heritage are even more explicit in the early drafts of the novel. In one of these ‘lost’ episodes, Tom Buchanan launches into an ugly prejudiced rant about Jewish theatre-types when someone mentions that ‘this man Gatsby’ lives in West Egg. Elsewhere the bully speculates that Gatsby might very well have sprung from the Lower East Side of Manhattan, a district which was this time dominated by Jews who had escaped the Tsarist pogroms in Russia — a line that eventually found its way into the mouth of Nick. And then there are those scenes in the novel featuring Gatsby’s mentor, Meyer Wolfshiem — scenes which are, quite understandably, likely to offend most modern readers. Scott makes little bones about the fact that Wolfshiem is Jewish. Worse than this, he’s presented as a Jewish stereotype, with all the various stock mannerisms of your typical gangster flick: “a small flat-nosed Jew raised his large head and regarded me with two fine growths of hair which luxuriated in either nostril. After a while I discovered his tiny eyes in the half-darkness.” [28] The man that Nick encounters is an oily, Mephistophelean figure. The man has a soft and sentimental charm but the very hair in his nostrils betrays any attempt at elegance. His movements are furtive and his speech unpolished. There is a unsophisticated and vaguely turbulent gentlemanliness about him, as if the shell might crack at any moment and some swollen, monstrous chick will tumble out.

The meal that Wolfshiem is eating with “ferocious delicacy” is a simple Hash, a meal that had first been introduced to American by immigrant Jews. It is your classic leftover meal: cheap chopped meats mashed up with potato and whatever else you could find to toss in. Meyer Wolfshiem (like the Lower East Side of New York) is Hash personified. He’s neither one thing nor the other. He’s not well educated but he’s not stupid, he’s tough and feisty but sentimental. He’s a kingpin bootlegger drinking Highballs, the poor man’s cocktail, and usually the lightest alcoholic drink on the menu. It would be like Al Capone enjoying a Spritzer. He has the money to dine at the finest restaurants but chooses the smaller one across the street where he eats the most innocuous food on the menu with joyful and simple abandon. He is a man living unpretentiously in a deeply pretentious world whose power and influence he accepts, but refuses to engage with fully. For all his villainy, Wolfshiem has a warmth that is totally absent in the Buchanan household where dinner is consumed with a “bantering inconsequence” that is as cool as their outfits and their “impersonal eyes”. [29]

After finishing the meal, Wolfshiem makes his excuses to leave. Gatsby makes a courteous but less than enthusiastic appeal for him to stay, but Wolfshiem waves the suggestion away, raising his hand “in a sort of benediction”. [30] It is a throwaway line from Scott who is clearly enjoying the gently religious nuances of the scene. A benediction is traditionally a blessing given by a priest as they wave their hand, usually at the end of communion or confession. Scott recycles the word again in Chapter VIII when Gatsby describes the sinking sun of the evening as “spreading itself in benediction” over the spot where he had last seen Daisy before she married Tom. The mashing up of secular, pagan, Jewish and Catholic imagery is perhaps Scott’s way of uncovering commonalities among all these groups; the rituals and traditions that most people observe without even knowing it: the things people say and do to form bonds or show their respect. Offensive to Catholics or not, it is still an anti-Semitic scene. There is little doubt about that Scott is drawing on prevailing Jewish stereotypes but to my mind at least, Fitzgerald is not expressing anti-Semitic sentiments in Gatsby, he’s exploring them. Whilst this in no way excuses his abject failure to challenge these views head-on, its entirely consistent with the non-judgemental nature of the book’s narrator.

The world that Nick inhabits is ruled by appearances and misconceptions. Although predominantly concerned with the imaginary threat posed to the American gene pool by non-Nordic races at this time, Lothrop Stoddard did, as we have seen already, offer some fairly bleak predictions about the triumph of the Russian Bolsheviks in the Revolution of October 1917, an event that he believed would spell the ruin of the whole of the civilised world. Like most Conservatives of the period, Stoddard mistakenly believed the Bolsheviks to be Jewish (“Bolshevism with Semitic leadership”). The Bolsheviks’ “furious hatred of constructive ability and its fanatical determination to enforce levelling”, Stoddard explained, “had vowed the proletarianization of the world, beginning with the white peoples”. Their actions not only fomented social revolution within the white world itself, the Bolsheviks also sought to enlist the support of the world’s black communities in its ‘grand assault’ on civilization: “In every quarter of the globe, in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the United States, Bolshevik agitators whisper in the ears of discontented colored men their gospel of hatred and revenge.” [31] As far as Stoddard was concerned, the Blacks with the support of the International Jews had hatched a conspiratorial plot to rule the world.

The brutality of Stoddard’s vision had already been laid bare in May Day, a short-story by Scott that had appeared in The Smart Set a few years earlier. The story presented a particularly unsettling picture of a baying mob clustering around “a gesticulating little Jew” who is questioning the wisdom of the war. As the poor man continues his speech, a fist lands upon his chin. “God damn, Bolsheviki!” cries one of the men to a “rumble of approval”. [32] The issue of scapegoating in which the internal contradictions and anxieties of the dominant class are taken out first verbally and then physically on a man of doubtful class and uncertain ethnic origin would be picked up again in The Great Gatsby, albeit in a more subtle fashion.

continue reading: Eugenically Speaking: Love or Eugenics?

Some of the views on religion and politics being expressed in this article are an attempt to articulate the various themes and narratives being explored in the novels and essays cited. They do not necessarily reflect my own views. The above article is taken from Becoming Gatsby: How the High Priest of the Jazz Age Wrote the Gospel of the American Dream (Alan Sargeant)

[1] Why Europe leaves Home: A True Account of the Reasons which Cause Central Europeans to Overrun America, Kenneth Lewis Roberts, Bobbs-Merrill, 1922, p.48; ‘Suds’, Kenneth L. Roberts, The Saturday Evening Post, October 27, 1923 Vol. 196 Iss. 17, p.10

[2] Restriction Of Immigration Hearings, The Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, House of Representatives, Sixty-Eight Congress, First Session, Dec 1923-Jan 1924, pp. 608-620

[3] Restriction of Immigration, Hearings before the Committee on Immigration and Naturalisation, House of Representatives, 68th Congress, First Session, December 1923 – January 1924, pp. 388-389; Why Europe Leaves Home, Kenneth L. Roberts, 1922, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1922, p.47

[4] ‘Theory of Blond Supremacy Makes Powerful Appeal to Mind of Layman or Scientist’, Frederic J. Haskin, Iowa City Press Citizen, April 9, 1923, p.7

[5] ‘Black Oxen’, Gertrude Atherton, Boni & Liveright, January 1923, p.90

[6] ‘Choose Vital interest in Life and Stick to it’, Gertrude Atherton, Brazil Times, Indiana, June 16, 1923, p.4

[7] ‘Blondes Dying Out in America’, Elbert County Tribune, August 16, 1919, p.3; ‘The Shape of Your Head Reveals Your Radical Tendencies’, New York Tribune, June 29, 1919, p.9

[8] This Side of Paradise, F. Scott Fitzgerald, p.140

[9] Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy, Lothrop Stoddard, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1921, p. 164, p. 259. The book that The Rise of the Coloured Empires takes it inspiration from.

[10] ‘Fitzgerald’s Princeton Through the Prince’, Ann Margaret Daniel, F. Scott Fitzgerald in the Twenty-First Century, University of Alabama Press, 2003, p.16

[11] ‘A Negro View of the Presidential Candidates’, Quincy Daily Journal, August 16, 1912, p.4

[12] This Side of Paradise, F. Scott Fitzgerald, edited with an Introduction and Notes by Philip McGowan, Oxford Words Classics, 2020, p.83, p.90, p.113, p.254

[13] On the Genealogy of Morality, Friedrich Nietzsche, Cambridge texts in the History of Political Thought, eds. R. Geuss, Q. Skinner, Cambridge University Press, 2006, p.58

[14] ‘Dr Chapman’s Lecture on the New Evolution’, The Voice of the People, October 8, 1914, p.3

[15] ‘German Atrocities: The Estimates of Goethe and Heine Justified’, New York Tribune, March 9, 1918, p.9; The Blond Beast, Fiction, Publishers Weekly, May 25, 1918, Vol. 93, no.21.

[16] Preaching Eugenics: Religious Leaders and the American Eugenics Movement, Christine Rosen, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp.95-96

[17] ‘August Jeansonne’, Yuma Sun, Arizona, April 15, 1923, p.2

[18] Scott tells us that the colour of Pamela’s hair is yellow (“did mother get powder on your yellowy hair?”, TGG, p.111). On the following page Daisy says that the child has got her hair and shape of face (TGG, p.112). On page 143, in which Nick describes Daisy and Gatsby’s parting in 1917, he writes of Gatsby kissing her ‘dark shining hair’. Had Daisy dyed her hair blond sometime between October 1917 and June 1922? Or is a continuity error?

[19] Blonds and Brunets, Katherine M. H. Blackford MD, Review of reviews Company, 1916, p.10; ‘The Fair Haired Men of the Aryan Race Giving Place to the Sons of the South’, Wood County Reporter, November 15, 1888, p.5

[20] The Appetite of Tyranny, G.K. Chesterton, Dodd Mead and Company, 1915, p. 120

[21] The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald, p.124

[22] The Palmer Raids, Robert W. Dunn, International Publishers New York, 1948 p.69. baker’s address was made in January 1920 at the House Ways and Means Committee. The so-called ‘Red Scare’ had entered a critical phase.

[23] ‘Bolshevik Danger is Cited’, Fairfield Daily Journal, August 16, 1920, p.1; ‘Poland as Barrier’, Henry Noel Brailsford, New Republic, May 3, 1919, Vol 19, no. 235, p.10. President Wilson had used the phrase ‘barrier of civilization’ in his Veteran’s Day address in November 1919.

[24] ‘Inter-marriage is the solution of the Race problem’, Saint Paul Appeal, August 26, 1922, p.2

[25] ‘There is Confusion’, Jessie Redmon Fauset, The Monitor April 18, 1924, p.2

[26] The Revolt Against Civilization The Menace Of The Under Man, Lothrop Stoddard, Charles Scribners Sons, p. 179

[27] ‘White Niggers’, Deseret Evening News, November 15, 1898, p.3. Somewhere between 50 and 300 people were murdered when White Supremacists overthrew a democratically elected government as part of a racist insurrection. There were those who believed the word ‘nigger’ was not a corruption but an older term whose slanderous intent was much broader.

[28] The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald, p.68

[29] The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald, p.17

[30] The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald, p.71

[31] The Rising Tide Of Color Against White World Supremacy, Lothrop Stoddard, Charles Scribner & Sons, 1920, pp.220-221. The book that The Rise of the Coloured Empires takes it inspiration from.

[32] Tales of the Jazz Age, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1922, ‘May Day’, p. 77