The Fitzgeralds’ stay in Europe didn’t make any significant impact in the columns of the world’s press, the few exceptions being a 500 word review of This Side of Paradise in the Manchester Guardian on May 27th and a gossip item in Paris edition of the New York Herald the week before. According to the report in the Herald, the author and his wife had arrived in Paris on May 18th and were staying at the Saint James d’Albany Hotel on the Rue de Rivoli. Following the Fitzgeralds to the Saint James d’Albany at the end of May was Crown Prince Hirohito of Japan and his diplomatic and military entourage. Just days before, the Duke of York had hosted a special dinner in his honour at the Hotel Cecil. [1] By the end of the month, the Prince had completed his tour of London and planned, like Scott, to continue south to Italy in July where he met with Pope Benedict. Also like Scott, it was London that had made the deepest impression on the young prince who was astonished by the freedom that the British Royal family enjoyed and the warm, informal way that they engaged with the public.

The Saint James d’Albany Hotel was every bit as large and as lavish as the Cecil. As the former home of Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette it had an interesting link to America too, the energetic French Aristocrat having played a key role in the victory at Yorktown, the battle that secured George Washington’s win over the English in the War of Independence. With its view over the Tuileries Garden the hotel’s gorgeously ornate dining room had its fair share of devotees, among them Gilded Age eccentrics like the ‘unsinkable Molly Brown’, the larger than life survivor of the RMS Titanic. The couple couldn’t have picked a better base for sightseeing, located as it was between the Louvre and the Place de la Concorde, just a stroll of the British Embassy.

It was whilst staying at this hotel that Zelda, pregnant with Scottie at that time, would infuriate staff and other guests with her determined efforts to keep the cage doors of the elevator door open. If the doors didn’t close, they didn’t move. And if they didn’t move then the guests in the penthouse suites above and below them wouldn’t be able to use them. Either she wasn’t aware of the etiquette or had decided to ignore it. Scott’s friend Edmund Wilson would relate the story to John Peale Bishop: “The story is that they were put out of a hotel because Zelda insisted upon tying the elevator—one of those little half-ass affairs that you run yourself—to the floor where she was living so that she would be sure to have it on hand when she had finished dressing for dinner.” It was the first of many occasions in which the standard of conveniences didn’t match those of modern America. [2] Also arriving in France that week was American author Sherwood Anderson, whose self-probing series of stories for Joyce and Lawrence publisher, B.W. Huebsch, had won high praise from Scott and his friends. Stepping off the SS Rochambeau when it docked at Le Havre was Sherwood’s wife Tennessee, American newspaper publisher, Carter Harrison Jr and journalist Ernestine Evans, a close associate of Scott’s friend, Edmund Wilson who was on her way to Soviet Russia to observe the state of its famine crisis for the magazine, Asia. The New York Herald reported that she had arrived at the Grand Hotel Corneille on Paris’s Left Bank on or shortly before May 25th.

After checking in at the Hotel Jacob, Anderson and his wife had wasted no time at all in paying a visit to Ulysses booklegger and underwriter, Sylvia Beach and the Shakespeare & Co bookshop. The shop, which was newly opened, was located just a few minutes’ walk from their hotel on the bohemian Left Bank of the city. Whilst there, the Princeton-raised Beach would arrange for the pair to meet the book’s author, James Joyce (‘a handsome man with beautiful hands who lights up the room when he opens his mouth’) and Gertrude Stein. Joyce had arrived in Paris the summer before and had immediately set about finishing the book that had caused such a controversy back in New York. Responding to the efforts of John Sumner and the New York Suppression of Vice to have it banned in America, Joyce had struck up a deal with Beach to have it published in Paris by Shakespeare & Co. A letter written by Beach to her sister Holly at this time gives some idea of the excitement that it was generating “Holly I am about to publish Ulysses of James Joyce. It will appear in October—a thousand copies—subscriptions only … What do you think of that Holly!? … Ulysses is going to make my place famous. Already the publicity is beginning and swarms of people visit the shop on hearing the news.” On May 31 Joyce was writing to his professional associates asking to them send all future mail to Beach’s bookshop at Rue Dupuytren. A week later he was expecting the first of the proofs.

When Anderson and his wife met up with Joyce on May 30 he was just moving out of his lodgings at the Boulevard Raspail to a quieter and more comfortable apartment at 71 Rue du Cardinal Lemoine, just minutes from new arrival Ernestine Evans at the Grand Hotel Corneille. Joyce had stayed at the very same hotel when he had first arrived in Paris in 1902. During the passage to France, Anderson discovered the feeling one experienced when leaving America for the first time. It was like Christopher Columbus in reverse: “We go on and on steadily, leaving America behind, approaching the strange place. One begins to realize a new adjustment. America becomes for the time at least less important. It is vast but the sea is more vast. The whole continent, towns cities, states can sink out of sight over the edge of the world.”

On May 28th, a few days after Scott and Anderson’s arrival, the Paris edition of the Chicago Tribune ran a feature on Beach’s bookshop which was currently in the process of moving to its permanent new premises, 12 rue de l’Odéon: ‘Literary Adventurer: American Girl Conducts Novel Bookstore’. Described by the paper as one of the most interesting and successful literary ventures in Paris, the opening of the shop the previous year had been the courageous undertaking of Sylvia Beach, a swashbuckling 34 year old who had just returned from Serbia. Beach had been active in the Balkans since 1918 where she had been serving the American Red Cross. The unit to which Beach had been attached, the Balkan Commission, had been in Belgrade as one of ninety voluntary units from around the world trying hard to avert a terrifying humanitarian disaster. In the first few years of the war a temporary HQ had been set-up at the Hotel Regina in Paris and it was here that Beach’s love of Europe had been strengthened, a trip to Spain and Italy at the outset of war having whetted her appetite for travel.

The exact circumstances of Beach’s first trip to Europe are sketchy at best. Although a news item in her local New Jersey paper, the Trenton Evening Times says she was heading to Spain on health reasons, her passport application reveals that Beach was heading out to scout for material for a number of magazine articles. As passionate as she was about America, Beach was eager to expand her horizons, and the war in Europe presented just the right opportunity. It wasn’t Sylvia’s first encounter with writing, she and her sister had already provided invaluable support to Charles G. Osgood Jr, Preceptor of English at Princeton University, when he was working on his book on the poems of Edmund Spenser. According to Beach’s biographer Noel Riley Fitch, Sylvia had met with German-American publisher (and Henry Ford peace activist) Ben W. Huebsch in 1914 or 1915 to discuss a possible career in journalism. Huebsch, who would be among the first to publish works by Joyce and Sherwood Anderson, had been in Germany when war was declared and had remained there for several weeks as Assistant Consul in Leipzig. It was here that he found himself issuing emergency passports to thousands of British and American citizens looking for an urgent escape route out of the war. That Beach’s pastor father back in Princeton was a personal friend of President Wilson would have made her an attractive tap for inside information on America’s changing position on the war and her sharp, well balanced judgement would make her a very capable correspondent. She remained in Spain and Italy for two years before relocating to France.

Skip forward to Paris ,1919 and Huebsch and Beach are collaborating on another project. This time the plan is to put French authors in touch with American authors in the city’s rich and varied Latin Quarter. Central to the idea would be a bookshop that would also operate as a lending library. Within months of its launch the shop would see shoal after shoal of meandering, shabby-shoed writers dropping by to browse its wonderfully illicit and overcrowded reefs. A sign outside, designed by Charles Winzer, showed the bald old Bard himself and on one of the corner shelves inside the shop was a tiny porcelain model of Shakespeare’s home in Startford. The rugs and hangings in soft vivid colours that covered the floor and some of the walls had been brought back with Beach from Serbia. In the Tribune article, Beach is described as the daughter of the minister of the first Presbyterian Church at Princeton — Woodrow Wilson’s old church. Her younger sister, Eleanor, was working in movies in Paris, whilst her elder sister, Mary, was working as General Manager of the Red Cross mission in Florence. Letters written by Sylvia’s father from Princeton reveal that her mother, Eleanor, had arrived in Paris to visit her daughters at the end of March that year. [3]

Follies à deux

Scott never recorded the details of his arrival in Paris. His ledger records that the couple arrived in France on Tuesday May 17th and stayed until about May 25th when they made their way to Venice. Because the sequence of entries in the ledger are slightly jumbled in terms of chronology, all we know for sure is that he and Zelda paid a number of visits to the Café de la Paix soon after landing and a short time later had lunch with the tragic and ‘wistful’ Follies star Kay Laurell in the tea gardens of the Hotel Majestic with the actress Pearl White. Here they had eaten raspberries and cream, Laurell decked-out like a Christmas Tree in her ornate brooches, bracelets and bangles and long ropes of pearls. Sitting on top of her head like a star was a Rhinestone tiara. Any fight briefly put up by style had been roundly defeated by excess. In later years Zelda would recall the serenity of the occasion. Beside them a fountain had whirred and a cool ribbon of air offered some momentary relief from the heat. On one occasion Laurell had taken shade under a tree on the Champs-Élysées. Sitting there she had looked and smelled like a daffodil, a compelling combination of ‘lemony perfume and Bacardi cocktails’. Scott’s friend, H.L Mencken remembered her as the girl who came on during the grand finale of the show waving the American Flag. As a regular visitor to the offices of The Smart Set, Kay could usually be relied on for her encyclopaedic knowledge of town scandal. She had once told Mencken that it was easy for a woman to get money out of men by sleeping with them, but thought that it took real skill to get the money and avoid the sex altogether. Mencken recalled that one of her victims had been Otto H. Kahn, the flamboyant millionaire who had sailed with Scott and Zelda to England and then followed them across to Paris. Much of what he learned from Kay, Mencken confessed, would go into his 1922 revised edition of In Defense of Women.

Like Scott, Laurell had arrived in Paris from London in May and had spent the next eight weeks learning the language after being given the lead in a new play in one of its boulevard theatres. Also like the couple she left ahead of schedule in August. An offer that had just come in from New York had been just too good to turn down. The press of the time showed picture of the actress posing on the decks of the RMS Aquitania, making it reasonable to assume that she had made the journey to England on the same boat as Scott and Kahn.

Scott’s ledger mentions a trip to Versailles where the Peace Treaty was signed, but no further details of the visit remain. If the manuscript version of his short story A Penny Spent recalls episodes from his own life in the same way that some of his other stories did, then Scott may have paid an excessive sum of money for the pleasure of taking supper in the gallery of the Hall of Mirrors where the terms of the treaty were agreed by Wilson and the allies in June 1919: “I’ve had good times beyond the wildest flights of your very provincial middle-western imagination,” boasts one of the characters, “when you were still playing whose got the button back in Ohio I gave a midnight supper in the gallery of Mirrors at Versailles that cost fifteen thousand dollars in bribes alone.” Even if the story had not been inspired from life it may yet give us an insight into Scott’s feelings about the treaty. For many Americans, President Wilson’s pursuit of the League of Nations had been nothing short of foolish. He was an idealist to a fault, overtaken by, or so it was thought, by a combustible mixture of pugnaciousness and religion. In his book The Rising Tide of Color, Lothrop Stoddard would go so far as saying that the treaty he had signed in Versailles would lead to a future Armageddon. On a smaller, less hysterical scale, the promise that he had broken to remain neutral during the war had alienated him from many, including his own friends. In the last few years of his Presidency Wilson had suffered a series of debilitating strokes that saw him withdraw further and further from public life. Freud would later write that there may have been an intimate connection between the President’s alienation from the world of reality and his religious convictions. The excessive quality of his hopes were viewed by many Americans not only as extravagant but completely delusional. What better way of highlighting the cost of Wilson’s folly than by hosting a fifteen-thousand dollar supper in the room where it all took place?

Whilst Scott was careful not discuss the politics of the war openly with his readers, there are some clues in letters he would write to his friends. In one, which he wrote to his old pal at Princeton, John Peale Bishop, Scott joked that he was working on “a historical play about the life of Woodrow Wilson.” Written as he awaited the publication of Gatsby in Capri, Scott continued his drunken letter with a sketch of the first four acts of the play. The acts featured a surreal and dreamlike run of events and characters, from Princeton trustees Wilson and Moses Tyler Pyne quarrelling about the university’s elitist Eating Clubs to the arrival of Broadway stars Al Jolson, Marilyn Miller, sports guru, Grantland Rice and the French Prime Minister, Georges Clemenceau. The so-called Eating Clubs of Princeton had been a long running bone of contention at Princeton. When President of the University Wilson had tried to have them banned, regarding them as elitist, snobbish, and a constant distraction to studies. It was Wilson’s opinion that the various social barriers that Princeton had worked so hard to remove where being amplified by the clubs. No one was more aware of this than Scott, who made the “detached and breathlessly aristocrat” Ivy Club the primary setting for his debut novel.

The fourth of the acts in his fantasy play is set at the Peace Congress and the second at the Gubernatorial Mansion at Paterson, New Jersey, a suburb of New York close to his old prep school in Hackensack. In this act, Wilson is signing papers in his office when he is approached by Tasker Bliss, the former Chief of Staff in the US Army who co-signed the Treaty with the President in Versailles. Bliss approaches Wilson with a proposition to let the crime bosses get control of Paterson’s silk industry and the strikes. Wilson responds tartly, “I have important letters to sign — and none of them legalize corruption.” It’s a comically elliptical and insane little episode, but one that hints at the author’s instinctive (if irreverent) grasp of politics.

Scott’s preoccupation with the Palace of Versailles and the Hall of Mirrors would continue in his third novel, The Great Gatsby. So obvious are the references that the author Robert Stone would begin work on his first novel, Hall of Mirrors after rereading it, and director Jack Clayton would use Hermann Oelrich’s Gilded Age mansion, Rosecliff as the backdrop for the Sun King’s West Egg mansion in his 1974 film adaptation of Gatsby. What many people won’t know is that Oelrich’s house had been built originally as a ‘factual imitation’ of the Petit Trianon at the palace. Although it’s unlikely it possessed anything as grand as a Hall of Mirrors it certainly had the same Marie Antionette music room as Mr Gatsby’s gothic gaff on Long Island. Curiously, for someone who Shane Leslie once referred to as the Apollo of the Jazz Age, the adjacent Apollo Room bore an oval stucco bas-relief depicting Louis XIV on horseback trampling down his enemies. On the ceiling was the Sun King, the god of art, truth and peace. Fact or fiction, there was a symbolic truth and a sense of aspiration in the episode either way.

The single reference to the ‘Folie’ in his ledger entry for Paris is almost certainly the Folies Bergere, one of the most dazzling and most decadent cabaret halls in the world at that time, and whilst punters may have kidded themselves that they were there for the music, the wall to wall nudity, erotic dancing and wild costumes were often a strong incentive. The show they took in was the C’est de la Folie Revue which had been running all summer. Translating quite literally as ‘This is Madness’ this spectacular two act review by Louis Lemarchand consisted of a tableaux of thirty-six sumptuous scenes featuring an exotic array of dancers, singers and motionless nudes. One of them would later write that the girls on the stage were making astonishing amounts of money just standing around the stage in yards of green tulle doing nothing more than looking important. Their hair, they said, was such an airy shade of blond that it was not really a colour at all, but a “reflector of light”. They stood on the stage “vaporous” almost. This particular show climaxed in a blaze of oriental glory with a harem orgy in the palace of Semiramis. It was a psychedelic vision, the coloured lights pouring onto the stage and through the diaphanous fabrics of the performers creating an overwhelming sense of excitement and chaos. Scott and Zelda would have sat there completely immersed in the spectacle before them, part-fascinated, part-disoriented and part-stewed on an inevitable heady cocktail of Bollinger bubbly and cocaine. The director of the show, Paul Derval had thrown in every titillating device possible to thrill an audience almost entirely made up of tourists. The star of the show on this occasion was actress, singer and dancer Inga Agni — young, beautiful and, as custom probably demanded, completely and fabulously high on whatever fuel was available.

In later years Zelda would speak of the “roseate glow of early street lights” and the dyed roses laid at the foot of the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine in Place de la Concorde. Her memories of the time are like the details of an impressionist painting. The whole thing is slightly defused and things are susceptible to change. In Scott’s letters of the period he would focus on the most superficial of realities and inconveniences of the trip, but in later recollections, only the lyrical and spectral qualities of the experience would be recalled, like how one could melt into the “green and cream Paris twilight” and have the feeling that you were standing “at one of the predestined centres of the world”. It was like taking away the heat and ferocity of the fire and being left only with its cosy orange glow. The best of its energy was residual. On occasions like these, hotels were no longer the source of constant irritation and disappointment but places “full of new people freed from the weary sequences of life somewhere else.” The stifling heat of the rooms had been forgotten and thoughts turned instead to the violets at the Café Weber and the sparrows of the café Dauphine.

In her own short story, The Original Follies Girl, Zelda would write of a Paris that was an intricate and fragile imitation of itself. She seemed to extend the analogy to the couple’s own lives and their own memories. The story’s heroine, Gay — a fictional approximation of their travel companion, Kay Laurell — is seen struggling to hold onto something that had never completely taken form in her life. She wanted to get her hands on something tangible, something real. She could no longer square up the things that had happened in the past with her memories of the past. The past wasn’t quite real, somehow. Like herself it had all been some kind of masquerade. And this is how it was for the couple. Their failure to engage with all that was happening at this time, to fully give birth to the moment, would give their first trip to Europe the thin, elusive quality of a dream. In all fairness, they were too much like Paris themselves. They were just too self-conscious. A little too aware of the buzz they had created around themselves, and a little too dependent on it to be anything close to ‘real’. Any judgements they had of the place could never be objective.

To get a better idea of what Paris was like at this time, and Scott’s possible state of mind on his arrival, we have to turn to Sherwood Anderson. Writing in his notebook on May 28, Anderson described how shortly after landing in Paris he and his wife had stood and absorbed the full, impossible history of the place: “The streets here are haunted by memories. To stand for an hour in the great open space facing the building of the Louvre is worth the trip across the Atlantic. We walk thro all these streets haunted by the ghosts of great artists of the past.” The city was like another world entirely, the French skies having a “special kind of pearly clearness”. In a way that showed Anderson’s instinctive, Emerson-like grasp of the transcendental the author described how the clouds had erupted in the sky like beacons. Their vaporous, elongated shapes had the effect of luring you somewhere. Reflecting in his diary on May 30th Anderson shared an almost out of body experience: even amidst the roar of the city, staring out across the uninterrupted skies of Paris made it seem like you were always on the point of floating away with them. By contrast, New York was a city cramped by shadows. No matter how bright the sun or how blue the sky, you could walk for twenty blocks without your eyes once being able to rise beyond the two-hundred feet buildings on every side. A cloud in New York was an isolated thing that led you nowhere. The skies of Europe, on the other hand, mapped out a route to better things.

As the days wore on Sherwood would also observe that many of the Americans who stayed here were like badly behaved children. There was a total lack of synchrony between these delinquents and their hosts. Time moved at a different pace here too. The author couldn’t get over how every day at noon the shops in Paris would close for a couple of hours and everyone would make to a cafe to tip down one of those new Espresso coffees or a glass of wine. [4] Scott and Zelda were not quite so lyrical about it. The wine and the coffee was one thing, but they often boiled “with ancient indignation” towards the city’s fusty, old-fashioned natives. One afternoon they drove to the Bois de Boulogne, a sprawling idyllic woodland two and half times the size of Central Park. Here they would reimagine France as a “spoiled and vengeful child” selfishly obstructing the progress of the world with its dense and oppressive antiquity. [5] The country was like a clock that had stopped ticking. It sat on the shelf offering only the dullest of sounds, its stiff little hands squeezing the life out of time, mechanically conserving history. Modernism for Scott was taking root in a mausoleum. The weak little oars pushed forward, and the current pulled you back.

At some point during the week, Scott had Zelda would drop their sightseeing chores and head through the Tuileries Gardens and across the Seine to the Latin Quarter of Paris. Here they would meet for lunch with Edna St Vincent Millay, a friend of both Edmund Wilson and Sylvia Beach, who had found temporary digs at the Hôtel de l’Intendance on the Rue de l’Université. Just nights before she had seen a “Negro orchestra and quartette” and it had made her homesick for the furious jazz of life in Greenwich Village. The sound of the band had been “rich and deep” and had struck exactly “the right bass note”. Sadly the lunch date with the couple would leave the most polarised of impressions on the Left Bank poet. In an anonymous article for The Bookman the following year, Edmund Wilson would describe Millay’s feelings about her encounter with the couple. According to Edna, meeting Scott had been like meeting a “stupid old woman” who had been left the most magnificent and beautiful diamond. Everyone who met the woman would be surprised to find that such an ignorant old woman should “possess such a valuable thing.” It was during this meeting that Millay learned of Zelda’s juvenile pranks with the elevator doors that had got them thrown out of their hotel, and which she later relayed to Wilson. The prank had clearly informed her judgment.

In translation it wasn’t quite so bad: Millay thought that Scott had an enormous talent that he wasted on all the wrong things. It was an opinion shared by Scott, who conceded in later years that whilst many Americans had lost much of their wealth in the crash of ‘29, he had lost everything he had wanted “in the boom” at the start of the decade. [6] For all his extravagance and seeming wealth, his diamond “as big as the Ritz” enjoyed a lousy exchange rate with the satisfaction he sought creatively. The picture painted by Millay was of a vulgar, bewildered genius, so overwhelmed by the suddenness and ferocity of his success that he couldn’t even guess at its value. This precocious and inelegant pretender had in his possession one of the largest and roughest of diamonds that he couldn’t cut and couldn’t polish.

Wilson conceded that Millay wasn’t getting the full picture of Scott by any means. Maybe she’d got him on a bad day. Nevertheless he believed there had been a “symbolic truth” in what Millay was saying: Scott had been given a stunning imagination but didn’t quite know what to do with it. He wasn’t stupid, far from it. He was both amusing and clever. Nevertheless, Wilson was of the opinion that the extraordinary gift for expression Scott had, had been robbed of its intrinsic value by having no actual ideas to express. Wilson hadn’t been particularly impressed with his debut novel. In his opinion it had almost “every fault and deficiency that a novel can possibly have”. It was also “not only highly imitative” but had been imitated “from a bad model”. A few weeks later Scott, still smarting from what Wilson had written, mailed his old friend a letter, updating him on the progress he was making with his play, The Vegetable. On the letterhead above it, in bold print were the words F. SCOTT FITZGERALD — HACK WRITER AND PLAGIARIST.

In their dismissive and fairly unreasonable account of the encounter, Millay and Wilson had articulated something that Scott had always known about himself: the charm and the razzle-dazzle masked a deeply insecure man. He was a parvenu, a fraud. Like his most famous creation Jay Gatsby, Wilson had described Scott as a “rather child-like fellow, very much wrapped up in his dream of himself and his projection of it on paper.” [7] There was something “gorgeous” about him Millay conceded, a raw and unbridled energy, but any promise that he showed was built more from the exceptional hope and optimism the young man possessed rather than from any clear, purposeful talent. The “sort of magic” that he had in abundance was an expensive and unsustainable trick. Nobody knew better than Scott how “terribly lucky” he had been. [8] The whole issue of him being an impostor had been explored in his debut novel when his fictional alter-ego, Amory Blaine tells his headmaster, Monsignor Darcy that he has lost “half his personality in a year”. He had begun to lose his standing among the other boys at the school. The children had begun to rumble that he was not as gifted as he often boasted. Darcy responds by telling him that all he had lost was his “vanity”. As far as his mentor was concerned, the “glittering possessions’ that the boy now grieved over were no more than the hefty chains of the ego, the things that kept him down.

For Amory, and one might assume for Scott also, the loss of those ‘glittering possessions’ — the diamond that he showed off to everyone — now threatened to reveal him as the impostor he thought he was. It seems obvious that the excessive boastfulness that characterized Scott as a boy masked some intense insecurities. Father Fay (Darcy in the book) appears to have identified this character flaw pretty quickly. The elaborate labyrinth of lies and half-truths upon which Scott had been sculpting his ‘personality’ was not encouraging growth but stunting it. Fay was keen to have the boy enjoy a ‘clean start’, but for Scott, letting go of those possessions — the successful projection of high-charm and high-achievement, all the things he thought he lacked — risked exposing him as a fraud. The mask would slip and the truth would come out. It was your classic ‘impostor syndrome’. As a response to his insecurities, the young Scott had embarked on a system of over-compensating. His precious ‘personality’ was no longer a screen but a wall. The mask that he had worn had become his castle keep; his boasts were his only defences.

This persistent fear of being exposed as a fraud would continue until his death in 1940. Scott seemed to see himself as a social plagiarism, a human Xerox machine, turning out copy after copy after copy. Scott reveals as much in an entry he makes in his Notebooks: when he liked someone he wanted to be like them. He wanted to lose his existing shell and take the shape of whomever it was that impressed him at that time. He was quite literally the glass of fashion, the mould of form. In a process not unlike that of permineralization, he wished to “absorb all the qualities” that made them attractive, instantly replacing his lesser organic matter with their own superior minerals, until nothing of his host remained. Like Gatsby in Nick’s cottage waiting for Daisy to arrive, Scott swung nervously between believing in himself totally and having no self-belief at all. Was Scott’s decision to kill off Gatsby at the end of the book an attempt to kill-off his inner-fake or might it be seen as an indication that he no longer needed it to function creatively? Gatsby the man turned out to be most magical and successful of shams, the God of verisimilitude.

The novel had originally come with a prologue that offered a glimpse of Gatsby’s Catholic upbringing in Minnesota. It showed a boy with talent for lying and playing roles. A boy who even in confession thought he had the skills to outwit God. “Solomon said that all men are liars,” Scott would tell his daughter, “Therefore what Solomon said was not true.” It was a paradox that he loved and kept repeating almost habitually to Scottie. In making sense of the riddle, he was making sense of himself. He’d been an impostor all through Newman, all through Princeton, and as America’s youngest and greatest author, he was an even greater impostor now. Despite the habitual, desperate boasts, the depth of Scott’s self-loathing would drive him to one drink and then another, and in his anxious, drunken state he probably thought that it was only ever a matter of time before his publishers saw through him too. In the words of Shane Leslie (or even Milton or Shelley) he was probably just another study in sublime failure.

By the summer of 1921 it was clear that Scott was reaching out for recognition, not as an author but as an artist. It wouldn’t come straight away. Not with his second novel, and certainly not with his play, but as this process of self-exfoliation continued the diamond that Scott had inherited slowly began to realise its true worth. Upon the completion of his first draft of The Great Gatsby in October 1924, Scott wrote to editor, Max Perkins: “I think at last I’ve done something really my own.” The ‘stupid old woman’ within him suddenly realised he had something of value.

The American Diaspora

Scott, Wilson and Sherwood weren’t the only Americans making the pilgrimage to Paris that year. Hemingway, Djuana Barnes, Stephen Benét, John Wyeth, Gerald and Sara Murphy and Ezra Pound had all been pasty-faced newbies there too. The Irish novelist, James Joyce had arrived in July the previous year and his publishers, Beach’s Shakespeare & Company, had just begun mailing out copies of a subscription form for Ulysses. Perhaps sensing a sudden wave of anarchy and subversion breaking out among the advancing army of ex-pats, the Paris Police Prefecture had just introduced a dedicated team of detectives to monitor all foreigners, 6, 000 of whom were American. Previously scattered among several different departments, this new centralised bureau, housed at 9 Boulevard du Palais, would comprise one hundred officers whose task it was to focus on identifying and deporting any political agitators and subversives — and, one might well imagine, apprehending any seditious prose or verse falling from the shelves from Sylvia Beach’s bookshop. Civlisation was going to pieces, or so it was thought. Shane Leslie’s summary of Joyce’s novel as ‘literary Bolshevism” was clearly being taken very seriously indeed.

In May 1921, America had imposed its dramatic and uncompromising Emergency Restriction Bill to tackle the problem of a Bolshevik ‘fifth column’. France on the other hand had gone about their work with their customary grace and elegance; instead of throwing the devils out they simply boosted surveillance. Instead of restricting immigrants they would make staying in France as complicated and as painful as possible. When tourists arrived at hotels they would now be obliged to fill out lengthy identification forms, whilst those intending to stay in the country would need to purchase identification cards. [9] The American diaspora would be formally crowned in July with the arrival of the new American ambassador, Myron T. Herrick, a well-adjusted capitalist who had occupied the post during the first few weeks of the war and earned something of a legendary status. At a special ceremony in his honour at the Hotel de Ville the previous year, Herrick had upscaled America’s commitment to post-war France. He didn’t just understand the needs of France, he understood its heart. [10]

Supporting Herrick that summer was Otto H. Khan, the unfathomably rich German-American banker who had accompanied Scott and Zelda to England on the R.M.S Aquitania just two weeks before. Their fellow passengers that week had been split fairly fractiously between those who were anxious to preserve Anglo-French-US relations and those were doing their darndest to cool them. In the former camp was Colonel Edward M. House who had worked with Shane Leslie in Washington during the war and Henry White, who, like Colonel House, had served as one of five special White House commissioners dispatched by President Wilson to the talks in Paris in 1919. In the latter camp was Harding’s brand new Ambassador to Britain, the tough-talking ‘Green Mountain boy’, George Harvey. In the first week of May, the Reparation Commission in London had met to agree the full multi-million figure expected to be paid by Germany for the chaos they had wreaked across Europe. The bill that Germany would eventually be served with was an astronomical $33 billion. Kahn, whose contribution to bringing America into the war had been significant, and whose efforts had been recognised and honoured by several allied nations, had steamed across to France to share his fears about the bill. In his estimation, the scale of the debt and the lack flexibility being offered to the Germans could never lead anywhere good. It his belief that the entire natural economic balance of the world was likely to suffer. Kahn predicted nothing less than complete economic collapse, chaos and civil war if the allies were to pursue their ‘iron hand’ policy. To make matters worse, “the arms of the Soviet” were reaching ominously out towards it. With collapse would come hardship, with hardship would come desperation, and with desperation would come Bolshevism. Not that Kahn was ever in any doubt about his loyalty to the allies. Ever since the inauguration of President Harding in March, and the appointment of George Harvey to Britain, Kahn had been waging war on US isolationism. After checking in with his family at Hôtel Plaza Athénée in the last week of May, Kahn had given a series of interviews to the French Press in which he renewed his commitment to Anglo-French-US relations even if he still had his doubts about the high idealism shown by Wilson for the League of Nations. On Independence Day he made good on that commitment by making a $50,000 donation to the French Navy.

Flying to Paris with Kahn that week was William Wiseman, the former Head of the British Secret Service in New York. During the war Wiseman had provided able support to Scott’s friend Shane Leslie in his dealings with Wilson’s adviser, Colonel House and then gained a global recognition as a ‘mystery man of peace’ at the talks in Paris in 1919. Shortly after the war, Wiseman had been taken on in a semi-formal capacity as adviser at Kuhn, Loeb & Co, where Kahn was serving as a senior partner. A news item in the Daily Mirror in August 1921 reports that Wiseman travelled to New York from England in June on the White Star liner the Celtic where he was believed to be carrying out ‘special work’ for the company. Joining him on the trip was movie star, Douglas Fairbanks Jr and two-hundred hopeful Irish girls, all eager and willing to flesh out the chorus lines of Broadway. For the duration of his stay in Paris, Wiseman had taken a room at the Hotel Meurice on the Rue de Rivioli, just a hundred or so yards from where Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald were enjoying the Gallic excesses of the Saint James d’Albany. By contrast, Colonel House, Wiseman’s US colleague at the peace talks, was enjoying the more opulent glamour of the Paris Ritz. Shortly after his arrival at the hotel on May 10th, House told a reporter of the New York Herald that he was delighted with Harding’s decision to allow American representatives to resume their place on the Council of Ambassadors after being withdrawn temporarily by the new US President in January. He then remarked that he had met with the new US Ambassador Harvey on the trip across on the Aquitania, and that he was “looking and feeling fit to take up his duties in London”. The Colonel and his wife would shuttle between Paris and London for the duration of the summer, arriving back in the United States in the last week of August. Harold Loeb, the son of Kahn’s co-director, Arnold Loeb, would get to know Scott through his literary salon and bookstore, The Sunwise Turn in Manhattan. The two Princeton graduates would also feature prominently in the career of Ernest Hemingway during his early years in Paris. According to The Princeton Alumni Weekly, Loeb was editing, Broom at this time. As Scott was discovering: the world wasn’t so big after all.

If Scott did manage to meet up with his old friend Father Hemmick, as Shane Leslie had suggested in his letter the previous autumn, it is not recorded. Hemmick, who Scott had known at prep school, was at this time busy in Paris helping to organise a supper dance on behalf of the Cercle de l’Union Interalliée. The club, located adjacent to the British and Japanese Embassies, had been founded in 1917 to mark America’s entry into the war. In the mid-1920s it would be used to host a Princeton alumni dinner given by its president John G. Hibben. Among those attending Father Hemmick’s supper dance in June 1921 were Marshall Foch and US Ambassador Wallace. In the immediate aftermath of the war, a whole new spirit of collaboration was taking shape. Clubs were being founded, trade was being brokered and deals were being made. The colossal losses of the war was now the glue that was bonding the old western nations together. A shared past was laying the foundations of a shared future. Just a few weeks earlier on Monday May 30th Hemmick had pronounced the Benediction at the lavish military ceremony at Suresnes on Memorial Day. That same day 19 year-old African American shoeshine worker Dick Rowland had what was probably quite an innocent encounter with an attractive white girl. Despite her protests the boy was arrested and charged with assault. The public reaction to the affair would become known as the Tulsa Race Riots, a devastating two-day wave of violence that resulted in the deaths of 36 people, black and white. [11]

For a man still smarting from the shame of not serving abroad, France was absolutely the wrong place to be. A country that was fit for heroes had little room for those who had never experienced battle. This was one party that Scott was probably quite happy to miss.

Memorial Day

Memorial Day in France that year was being organised as something special. The two day mini-event starting Sunday the 29th May would culminate in a ceremony at the Arc de Triomphe, a symbol of fraternity amongst the allies. A full itinerary of military and religious services had been arranged, the high-point being a slow, winding procession led by Ambassador Wallace and Major Henry T. Allen to lay a wreath at the tomb of the Unknown Soldier. On that day, The Garde Republican Band had opened with The Star Spangled Banner and British, American, Belgian and French troops all stood neatly at attention. Wallace had stepped forward and addressed the crowd: “I place this wreath upon the grave of the unknown soldier who rests here as the very type and symbol of heroic France. His body lies in the earth which bore him, but his spirit lingers near … this is not death, it is life supernal.” In one particularly reflective account, the New York Herald would describe how their countrymen would come to the tomb as they would to an altar where they may “imbibe the patriotism from a never failing source.” [12] Scott would draw on this reservoir of ‘supernal’ patriotism for both Gatsby (1925) and Tender is the Night (1934). In the earlier novel, Nick Carraway has arrived back from war wanting the world to be in uniform and “at a sort of moral attention forever.” [13] The romance of the war had provided young Americans with something they had been missing. But it wasn’t anything that was rooted in reality. Two years on from the war and Scott was beginning to see that much of what they had felt during that time had been rooted in fairy-tales, in dreams. When Dick and Rosemary visit the war cemetery in Tender is the Night, Dick believes that it been the mindless pursuit of romance — “a century of Middle Class love” — that had led to the outrageous scale of butchery on the Somme. It was an addictive, heady cocktail of religion and class dynamics that had invented this kind of battle, wrote Scott. It was the product of “Lewis Carroll and Jules Verne and whoever wrote Undine, and country deacons bowling and marraines in Marseilles.” [14] Towards the end of his life, Scott would write that his generation had been born into a period of “intense nationalism” where “Jingo was the lingo”. In words that shone a brilliant (green) light upon his famous ‘boats against the current’ metaphor, Scott would describe them as a generation that had inherited two worlds: “the one of hope to which he had been bred, and the one of disillusion which we had discovered early for ourselves.” It was that world that was now growing as remote as either France or Britain, “however close in time.” [15] In his study back at home was a rusted old German helmet and a bayonet. Those who saw the helmet remember that it had a small grim hole in the crown around which had dried a clump of caked gore that Scott let everyone think was human matter. [16] He later joked to his editor Max that he would present the manuscript for his new novel, Tender is the Night by visiting him in his office wearing the helmet. [17] If glory had eluded him through action, at least it could be his crown through words.

The fairytale of war was one that would come back to haunt Scott throughout his life. The “juvenile regrets” that Scott would refer to in The Crack Up would eventually rack-up into a recurring war dream in which the gallant Captain Fitzgerald, his regiment cut to rags, saves what is left of his command from the victorious Japanese. When he wakes he realises that he is only “one of the dark millions riding forward in black buses toward the unknown.” The greater “waste and horror” though was that which had amassed from “what he might have been and done.” The fate that had been due had eluded him back, and with it, his sureties of glory. His failure to serve overseas “had resolved into childish waking dreams of imaginary heroism.” All those hopes had been “lost, spent, gone, dissipated, unrecaptured”. [18] Scott had spent his youth dreaming of chivalrous battles waged on the spur of romance. But instead of courage and honour, he had found only greed, selfishness and corruption. For every great dream there was even greater disappointment. Not even the fantasy was enough to sustain him now.

A White, Unbroken Glory

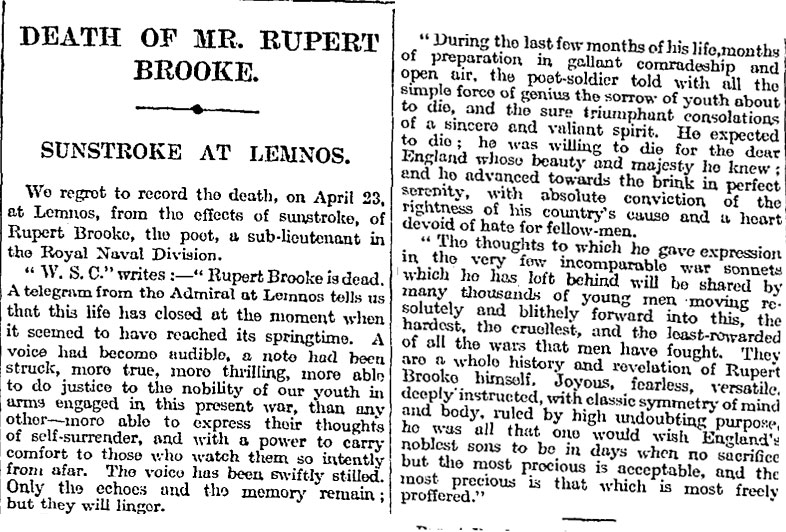

The irony of an ambitious young writer once feted as the ‘American Rupert Brooke’ arriving in Paris in time for the annual War Memorial wouldn’t have been lost on Scott. His fame and commercial value had hinged originally on being dead. Scott had drawn energy from Leslie’s pessimism. What had been his opening pitch to Scribners? “Though Scott Fitzgerald is still alive it has a literary value. Of course when he is killed it will also have a commercial value.” The death of Rupert Brooke had energized the recruitment drive in Britain. Few would have known that he died from sepsis from an infected mosquito bite. To Brits and many Americans, the idealistic young dreamer would become an emblem of tragic service — or, as Ambassador Wallace might have seen it, of ‘life supernal’. A breezy entry in Shane Leslie’s diary in September 1918 reads: “Stayed with Monsignor Fay and Scott Fitzgerald who is about to leave for France. Scott has become a romantic idealist. Thinks of taking the priesthood or meeting Rupert Brookes fate in the war.” Years later Scott would trace the onset of his debilitating insomnia to a mosquito bite. He never did explain whether the bite was his bite or the one that had elevated Brooke to his lasting, celestial status. Either way, he’d been infected. Scott knew this much: the grave of the Unknown Soldier possessed more mystery and more legend than any self-serving shrine put together by a famous living author. His arrival in France was being cruelly upstaged by someone who didn’t even have a name.

The man who had written the young Brooke’s obituary in The Times of London, was, ironically enough, Leslie’s cousin, Winston Churchill, the British Colonial Secretary that Scott and Zelda would meet during the first of their two week stays in London. Winston, then serving as First Lord of the Admiralty, had been keen to atone for an utterly disastrous landing in the Dardanelles. The obituary that Churchill provided was shaped by a genuine sense of grief for the loss of a genuine talent and the more cynical demands of politics. Brooke, who had been recruited into Churchill’s own Royal Naval Division, had written his most famous poem, The Soldier the Christmas before. The poem crystallised the sentiment of plucky British sacrifice so perfectly that it had been read on Easter Sunday at Saint Pauls just weeks before his death in Greece. Rather than repeat all that had been said on that occasion, Winston quoted some lines taken from another of Brooke’s poems, The Dead:

There are waters blown by changing winds to laughter

And lit by the rich skies, all day. And after,

Frost, with a gesture, stays the waves that dance

And wandering loveliness. He leaves a white

Unbroken glory, a gathered radiance,

A width, a shining peace, under the night.

This wasn’t a life wasted, Churchill fondly susurrated, but a life given. Winston, safe in London, philosophized that there was nothing of waste in what had been so “joyfully been laid down.” Brooke had given his voice to youth. That voice may have been “swiftly stilled”, he went on, but the echoes and the memory of that voice would remain and linger forever. [19] The death of Rupert Brooke on Saint George’s Day from a violent gastric episode was poetically reimagined as the fulfilment of a heavenly plan for the allies. Brooke had not only become a symbol of national political importance but a justification of every careless failure and every reckless loss suffered by the Churchill and the British Admiralty. He hadn’t died, he had martyred himself. For everyone between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five, the death of Brooke had quite become quite literally a death to die for. Greatness was still greatness, even if it was granted posthumously.

At the beginning of America’s war, Scott had, probably with Leslie’s backing, ploughed all his creative energies into a book of verse, but by December 1917 the idea had been abandoned. Writing from Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, Scott had told Leslie that he had completed some twenty poems but felt unable to continue in the prevailing “atmosphere” at the camp. These attempts — and Leslie’s offer of putting it before his publisher — were mentioned in the very first lines of the book’s original manuscript. The book’s hero, Amory Blaine, tells us he to write a “volume of poetry” and that “Theron Cary would take it to Scribners.” [20] According to a letter written to ‘Bunny’ Wilson some months earlier, the poetry that Scott had produced during this period had been written mostly under the “Masefield-Brooke influence”.

Several weeks later the author had changed his mind. Scott had neither the time or the patience to write more poems. He was now going to put down the experiences of what might be his very short life in prose, a mixture of “fiction and autobiography.” What was real and what was art was becoming fabulously blurred. It was a study in autobiography with a peculiarly avant-garde, self-reflexive twist. Scott had found himself writing his first novel about a precocious undergraduate writing his first novel. What could be possibly be more modern than that? The young writer stood self-consciously at the threshold of a two-way infinity mirror that he would spend his early adult life trying to escape. A division at a quantum level had taken place. From now until his third novel, Scott would find himself reflecting back at the world what the world sought from his own super-polished self-idea. This had been nowhere more apparent than in the self-penned interview he had prepared for publicising his first novel: “The author of This Side of Paradise is sturdy, broad shouldered and just above medium height. He has blond hair with the suggestion of a wave and alert green eyes — the melange somewhat Nordic— and good-looking too, which was disconcerting as I had somehow expected a thin nose and spectacles.” Written in the third person, Scott was probably hoping that the lazy or overworked editors of national newspapers would skip the custom of having some staff journalist rework in the house style and publish it largely intact. As an exercise in controlling brand narrative it was way ahead of its time. Scott had concocted a concise, and overwhelmingly positive messaging framework that he could communicate through his own rose-tinted lens some wonderfully idealised version of himself. His idea of himself as celebrity author was taking shape. In one side of his pen was Scott, privately fretful and ferociously insecure, and on the other there was ‘F. Scott Fitzgerald’, spokesman for a generation. Scott was floating his talent as public shares. Any stock he had wasn’t private now but for everyone. The brash ‘Romantic Egotist’ was slowly reinventing himself as the glass of fashion, the mould of form. One journalist who would see right through this was Heywood Broun, who would share his response to Scott’s sheet in the New York Tribune within weeks of the book being published. The review, which included substantial quotes from the author’s self-penned press sheet, concluded with an assessment that wasn’t too wide of the truth: “Having heard Mr. Fitzgerald, we are not entirely minded to abandon our notion that he is a rather complacent, somewhat pretentious and altogether self-conscious young man.” [21]

The eventual title of his debut novel, This Side of Paradise, would, in actual fact, be lifted from Brooke’s poem, Tiare Tahiti, written during his travels in the South Pacific, immediately before the onset of war. Brooke’s gently satirical poem told the story of the idle pursuit of glory in the afterlife of heaven. As America entered the war, Scott had become utterly convinced that he would suffer the same fate as Brooke and his classmates at Princeton like Jack Newlin. Scott would later write that in those days it was thought that all the men training as infantry officers had only three months to live. In his own words, he had left no discernible on the mark on the world. Because of this, he anxious to finish his novel as soon as possible, the heroic romances of Sir Walter Scott adding an encouraging symmetry to the blithe downpayment of his dreams: “Fight on, brave knights! Man dies, but glory lives!” [22] Every evening he would conceal his notepad beneath Captain Alfred Bjornstad’s Small Problems for Infantry and write paragraph after paragraph on “somewhat edited history” of himself and his “imagination”. Waiting for his orders overseas Scott had started work on his passport to immortality.

The maudlin, morbid energy shown by Scott and other talented youngsters was clearly something that Leslie and his associates at the Department of War in Washington could work with. That August, Leslie told Scribner that Scott’s novel would give expression “to that real American youth that the sentimentalists and super patriots” had been so anxious “to drape behind the canvas of the Y.M.C.A.” He said much the same thing to Scott, but had whetted Scribner’s appetite with a more exciting dimension — with any luck, it might get banned: “you may depart in peace and possibly find yourself part of the Autumn reading banned by the Y.M.C.A. for use among troops!” Leslie had probably sensed that Scott was still too much of realist to subscribe to the romance of dying for one’s country, or the “hero stuff” as he told his mother. Scott had told Mollie Fitzgerald that he had gone into all this quite, “cold-bloodedly.” All his reasons had been socially driven. Nevertheless, he feared the worst and if the worst was going to come then at least there would be a lasting echo in life left in print for the world to sigh over. In fact, the closer his passing got, the more eager he seemed to have it, as if it was the one route guaranteed to restore his flagging fortunes at Princeton and with girls: “If you want to pray, pray for my soul, and not that I won’t get killed—the last doesn’t seem to matter, and if you are a Catholic, the first ought to. To a profound pessimist in life, being in danger is not depressing. I have never been more cheerful.” [23]

To put it in the glibbest of terms, Scribner had taken Leslie at his word and signed a dead poet to their roster of Conservative talent. Luckily for them, Scott had made them money without being cut to ribbons leaping heroically from one trench to another in northern France, or dying of dysentery as he waited for battle. Being a famous novelist who still responsive to the full gamut of experiences in life had suddenly more attractive, more lucrative and almost certainly more enduring than a glorious death. Somehow, he and Zelda had captured the spirit of the period and the period still had some life left in it. Ever since the publication of Scott’s book a nervous kind of energy had been rippling through the air. Sparks were being made. Scott had become the poster boy of “the wildest of all generations”. Liquor spilled from the copper stills of Chicago to the battlefields of the speakeasies on Fifth Avenue. The age of loss had given way to the age of excess. America, under Harding, started ramping up mass production and new borrowing opportunities and hire schemes were allowing more and more people to benefit from these goods. After a temporary dip in fortunes, balances were being restored.

The ravages of the war had stimulated America into overproduction and now there was an overabundance of energy and meaning, not just for Scott but for everyone under the age of thirty. Usually, the only real way of countering loss is by ramping-up the value and the accumulation of ever more meaningless things. This was the same after any war. There was more dancing, more sex, more carnival, more pleasure. For that moment on, it really was “an age of miracles.” [24] Scott may have spent the rest of his life feeling robbed of his romantic early death and all the fail-safe glory that came with it, but if Scott had had his way he would have crawled into the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and got ‘beautifully stewed’ that day. Instead, he left for Venice, leaving before the mass outpouring of grief that was Memorial Day on May 30th. For the moment, heaven could wait. He still had a few good nights left in Babylon.

Remaining in France for the next eight weeks or so were the couple’s travel companions, Kay Laurell and Pearl White. White, the more famous of the two, spent much of her time fending off enquiries about her marriage to actor and director, Wallace McCutcheon Jr. There was talk of a separation, a divorce even. One of the very few French newspapers who did land an interview with White were the Les Modes de la femme de France, who caught her at the Hotel Majestic. The reporter made their way to the Old Embassy district and visited White in her first-floor penthouse suite. The doorman, the reporter recalled, was clearly a war veteran. Ten decorations including the Legion of Honor were stapled handsomely to his chest. He opened the door and waved her in, his gallantry not compromised in any way by having nothing at all to gain.

According to the journal this was one of the most luxurious, if not the most luxurious hotel in Paris. When the reporter entered the suite, White was stretched out on a low divan, covered with gold cloth and adorned with a delicious electric blue tea gown. Kay sat smoking and drinking highballs in another corner of the room saying nothing. White knew exactly why the reporter was here and what exactly they wanted to talk about. The only reason she’d granted the interview was because it was a reputable and really quite swanky fashion and beauty magazine. Prepared for the inevitable grilling, and fending them off with carefully prepared statement, White told them she didn’t yet het know if her husband had been unfaithful, and consequently, had no firm plans to divorce. [1] Laurell kept a watchful eye on her charge. Her husband, Winfield Sheehan was White’s employer at Fox and was keen to avoid anything that might be considered sleazy. Just one careless word could have seen the whole thing fall apart. All their stars, including Laurell, were being presented an ‘Ideal American Girls’. The illusion that they created on the screen had to be preserved at all costs. Investors and sponsors were at risk. Whilst nobody was quite sure where the lines that divided the character from the actor were located exactly, it was generally thought that the secret life of the studios was getting dangerously out of hand. The public was getting concerned. A veil was being pulled back to reveal the inner machinations of the dream industry and the loose morality on set was beginning to spill over to the screen. The stories were getting darker, the sex a little more extreme. Things would come to a head in September that year when actress Bambina Maude Delmont accused film star Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle of a violent sexual assault on bit-player Virgina Rappe at a Labor Day party at a hotel in San Francisco. During the trial the court heard how Arbuckle had plied the young woman with gin and whisky before dragging her into his room and raping her. Delmont described gaining entry to the room to find Arbuckle on top of the injured girl, his pyjamas wet with perspiration and wearing Rappe’s hat. The 30 year old actress died a short time later from her injuries, injuries which had been exacerbated by a body already ravaged by years of drug and alcohol abuse and weakened by venereal disease. The press went crazy with speculation, with everything from ice packs to coke bottles being cited as things that Roscoe had used during the attack. Despite Delmont’s testimony, Arbuckle was acquitted of murder. In April the following year a ban was placed on all his films at the behest of his own investors at the Lasky Studios. President Harding responded to the scandal by moving forward with plans for a Motion Picture Association, a self-regulating body intended to protect the investors on Wall Street. The temperance groups and reformers had their own ideas about the influence that film should come to bear on our lives: providing an education that we “might otherwise not gain”. For many ordinary God-fearing Americans, the motion picture industry was the most recent yet most powerful “educational force of modern society” but with that came a duty. Nothing in recent memory had there come something so potent “to model the manners and morals of the people”. The ideals being projected on-screen were best served to “modify conduct” and push the clearest, cleanest message about sex and marriage. In all fairness, the noise the movies were making was anything but silent and the beast needed bringing to heel.

By 1921, Scott had enjoyed his own roaring success in the movies: The Husband Hunter with White’s employer’s Fox, and two films with Metro and its leading lady, Viola Dana — A Chorus Girl’s Romance and The Offshore Pirate. That didn’t make him any less starstruck by the celebrities he met. His first encounter with Laurell had been lunch in the Japanese Tea Gardens of the Ritz Hotel in New York with their mutual friend the drama critic and Smart Set editor, George Jean Nathan, whose favour he had needed to curry ahead of the publication of his second novel, The Beautiful and the Damned. Scott’s idea had always been to play people at their game. Networking was something he had a natural, instinctive grasp of. He would spend hours in the company of those who could advance him in some way, mostly drunk, and quietly absorb all their magical traits and connections. The hosts would lose all track of time and any sense that anything was being stolen, Scott’s antics, perfectly choreographed for shocks, putting them completely off balance. For Scott, life had begun taken on all the characteristics of a German cotillion dance. You accustomed yourself to the rhythm, waited for a gap amongst the dancers and snuck in.

Between October and February 1921, Laurell and Nathan (a blatant Don Juan according to Mencken) had been a constant drain on energy, their appetites for fun being equal to, if not greater than Scott and Zelda’s. It was under their influence that Scott had spent too much time partying, too much on Plaza apartments and too little time writing. An entry in Scott’s ledger dated January 1921 read, “George Nathan and Sunshine Girl. Break with them.” The previous December Nathan and Mencken had published the jointly authored book, The American Credo a Contribution Toward the Interpretation of the National Mind. The book talked with authority on what it meant to be British or French, “whilst no American is ever so securely lodged.” The way these two young men of America’s literary elite saw it, there was “always something just ahead of him, beckoning him and tantalizing him,” just as there was “always something just behind him, menacing him and causing him to sweat.” The possibility of rising was accompanied by the constant fear of failing. Idealism was not a passion in America but a trade. In the absence of anything real, it was possible to conjure up something that at least passed for being real. Nobody knew that better than Scott. In his memoirs Mencken said that Laurell, like many in her trade, was possessed of “superior ornaments”. Her apartment was full of bookcases but the books in them were “mainly trash”. The need to be absolutely real had taken root in particular talent she had for being absolutely fake. According to Mencken she had an arrangement with Tiffany. Admirers would gift her with rubies and diamonds and Tiffany would buy them off her at a discount, replacing them with such convincing fakes that they fooled even the original donors.

During Scott and Zelda’s visit White and Laurell had paid a visit to the Aladdin’s Lamp club in Neuilly. The club at 21 Boulevard de la Seine had been opened by several members of the White Lyres Jazz band and 25 year old aviator, Clarence Merritt Glover just two days before the Armistice was signed at Neuilly town hall in 1919. [1] Captain Glover, a Yale graduate, had enlisted with the Norton-Harjes Ambulance Service during the war before joining Lafayette Flying Corps, a team of American volunteer pilots supporting France’s Service Aeronautique. According to travel writer Basil Woon, The White Lyres had been formed by Bill Henley, Kelvin Keech and Bob Dole out of what remained of the soldier’s orchestra. The jazz they played at journalist Jed Kiley’s clandestine meeting places was the first ever jazz played in Paris. During the war, restaurants and clubs were closed by 9.30 and the club operated in cheerful violation of the curfew. The result was a furtive, blossoming trade in secret clubs. Jed, who would become one of Hemingway’s closest friends in Paris, was at the forefront of the bloom. The dances at Aladdin’s, which held nightly soirees beginning at midnight, took place on the ground floor of a dignified mansion at 21 Boulevard de la Seine. [2] Who owned the house isn’t clear. All we know for sure is that it sat at the far end of a park surrounded by high walls and provided a discreet meeting ground for members of the armed forces and those in the ‘artistic’ and ‘sporting’ industries. Here the champagne corks kept popping like the Battle of Manila Bay. In December 1920 it was raided by Police for selling champagne at 50 francs a bottle outside hours without a license. Laurell and White would have blended in just perfectly. It was the pinnacle of Jazz Age decadence, sumptuously decorated like an Oriental Opium Den with jazz bands and an orchestra that knocked out the latest ‘rags’ and swing tunes. For those who didn’t come here to dance, there was enough ‘snow’ to produce a minor Arctic. A martini glass would be filled with champagne and a line of cocaine would be dabbed snortishiously around the rim. In a small ad run by the New York Herald, Laurell appealed for help in recovering a diamond and emerald bar pin that had been lost at the club. She would later tell reporters that the item had been gifted to her by the head of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, William A. Pinkerton. A reward of 10,000 francs was being offered for its return.

Just a few months before they arrived in France, one of Laurell’s Follies colleagues (and much loathed rivals) Olive Thomas had died suddenly in Paris. The rumours were as cheap as they were thrilling, with no end of ‘close associates’ spilling the beans on champagne and cocaine orgies. The reality was that she had died after ingesting, either deliberately or by accident, mercury dichloride, a prescription drug provided as treatment for her husband’s syphilis. It was your classic Hollywood Babylon story. A short time later Olive’s husband Jack Pickford was accused of dealing the drug. It was alleged that he’d been working with a dope dealer to the stars, Captain Spaulding, a regular visitor to the studios of the Famous Players-Lasky where Pickford plied his trade. According to some reports, the US Army veteran and his network were now being investigated by Police. It was, however, a world in which the silky smooth sauces of lies mixed easily with the thinner pretensions of truth and little evidence of the claims remain. Whilst the stories about Pickford and Thomas were likely to have been grossly exaggerated, there’s little denying that Laurell, Thomas and White had been hooked on these little perky little champagne supernovas for quite some time.

By 1921 the health and wellbeing of all three stars was in serious trouble. White died at just 26 and Laurell at 37. After her scandal-probe tour of Paris in the summer of 1921, the 30 year old White lasting just three more years in the business. The playwright Arthur Miller would recall that White’s movies had always ended a on a frustrating cliff-hanger: “her head an inch from a buzz saw or the train roaring down the tracks toward her trussed body or her canoe poised on the edge of a waterfall.” [3] It was little different in real life, only the effect was not quite so thrilling. By the thirties White was a blank and bloated caricature of herself, dying of cirrhosis of the liver after checking herself into the American Hospital in Neuilly. A glance over the press columns of the Paris newspapers in the early twenties reveals a series of major drug busts with heroin and cocaine among the biggest hauls. The buyers of the drugs were predominantly wealthy American ex-pats — the heroin sometimes compacted neatly into nutshells and passed discreetly from palm to palm by fast-talking couriers wearing two-tone oxfords. Occasionally sex was also up for grabs, with the so-called ‘buffet-flats’ putting on sex shows that offered punters direct engagement. There was nothing you couldn’t buy. Given the sheer volume of temptations on offer, it was nothing short of a miracle that Scott had managed to keep hold of his cash for so long.

Bastille Day

A month after the New York Herald had broadcast the arrival of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, the same newspaper would announce the arrival of Scott’s Princeton buddy, Edmund Wilson. Fellow New Yorker Wilson would repeat the same tortuous trip to France and Italy in July that year. Despite the pair’s best efforts to meet up, Wilson would miss seeing the Fitzgeralds by days. By the time that he had landed in France, Scott was already enroute to Rome. It was left to their old friend, John Wyeth — the “pure aesthete” they had known at Princeton — to share the news with Wilson, having dined with Millay and Scott just a few days before Wilson’s boat, the La Lorraine docked in Le Havre. A week or so earlier, Wilson had received a “bawdy French postcard” from Scott, signed Anatole France, but there had been other letters too, not all of them so light in tone. In a letter dated July 5th Wilson had responded to a violent tirade against Europe that Scott had embarked on from the Hotel Cecil. Edmund had arrived in Paris on June 20, several days after Scott and Zelda had left for Italy. At this time Wilson was still at the Mont Tabor Hotel and their various communications were out of sync. A short time later he relocated to a little guesthouse at 16 Rue du Four in the Latin Quarter of the city.

On June 22nd Wilson wrote to Scott bemoaning the fact that they had been unable to hook-up. At this point he knew nothing of the couple’s contemptuous view of Europe and Scott’s blistering Aryan wrath. That would become clear in a letter he would receive from Scott in early July. In his own letter, Wilson had been blithely updating Scott with news back home: the first instalment of Dan Stewart’s History had arrived, he had just left his post at the New Republic in “an aurora borealis of glory” and he’d also bumped into his and Kay Laurell’s friend, George Nathan who still seemed a little crestfallen after the quarrel that he and Scott had had before they left. The letter from Scott, expressing his particular fury with Italy, would be written on Hotel Cecil stationery and mailed to Wilson in Paris in the first few days of July. [26] We’ll be looking at the contents of the letter in a little more detail a separate chapter, but for now, all we really need to know is that the letter that Wilson sat down to write on June 22nd was a reply to an earlier postcard that Fitz had sent with instructions to leave a message at the Bureau American Express at 11 Rue de Scribe. Sadly, no such message ever materialised. Scott’s first letter reveals that he was as anxious to see Wilson as Wilson was to see him: “Edna has no doubt told you how we scoured Paris for you. Idiot! … We came back to Paris especially to see you.” In the event they weren’t able to meet, Wilson explained that he expected to be back in France that August should they fail to cross paths before then.

Someone else making the trip to Paris that month was US lawyer John Quinn, a friend of Scott’s London host Shane Leslie. He had arrived in the city fresh from representing Jean Heap and Margaret Anderson in the infamous Ulysses obscenity case. Wilson and Anderson had been virtually neighbours during this period: Wilson at 114 West 12th Street and Anderson’s Little Review offices at 27 West 8th Street. [27] Quinn continued to do everything in his power to get the book published. At the end of April, he had received disappointing news from B. W Huebsch and Boni & Liveright: there was just no way that either of them could publish an uncensored version of the novel without incurring significant fines or even a stretch in prison. His trip to Paris would lead him to explore other options.

America’s literary revolutionaries couldn’t have arrived in Paris a better time; on July 14th it was Bastille Day, the national anniversary of the gloriously iconic ‘Storming of the Bastille’ during the French Revolution of 1879. Acknowledging the friends’ Francophile sentiments Fitz had signed several of his letters ‘Anatole France’ whose book, Revolt of the Angels, was still rattling around his brain. [28] First published in 1914, the book had been an ambitious revolutionary allegory in the mould of Paradise Lost but with a Socialist-Catholic bent. Scott had fallen in love with the story and had derived inspiration from it several times already, most famously in The Offshore Pirate when the heroine of the story sits reclined in a wicker chair reading chapters of the novel. According to his Three Cities essay, Scott and Zelda had sat outside Anatole’s house in Paris for over an hour “in the hope of seeing the old gentleman come out.” Later that year France would be awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.

Quinn, a millionaire of Irish extraction who possessed the same vast energies and the same propensity for notoriety as the gold-hatted and high-bouncing millionaire, Jay Gatsby, had been in Paris to meet Romanian artist, Constantin Brancusi, a passionate Bohemian pleasure-seeker who he had been supporting and exchanging letters with since 1913. It was around this same time that Quinn had befriended Shane Leslie. According to Leslie’s biographer, Otto Rauchbauer, the pair’s union had been forged during Shane’s campaign for the Gaelic League in America in 1911, in which Quinn, the noble buyer and patron saint of the avant-garde, had been its most generous donor. Quinn had also stepped in to defend the managers of the Abbey Theatre after a spate of riots had broken out among Irish Nationalists unhappy with its depiction of an immoral Ireland in Synge’s 1907 play, Playboy of the Western World. Although critical of Leslie’s decision to focus more upon the broad events of Irish history than on the pressing needs of the League in his speeches, Quinn agreed with others that Leslie would help balance the more extremist (and anti-Modernist) side of the nationalist organization that had taken part in the Playboy riots. [29]

On the very day that the Manchester Guardian had published their review of Fitz’s debut novel, Quinn had written to Brancusi: “one can’t have too much of a beautiful thing.” [30] Quinn went on to explain that there was great beauty to be found in everything: in shapes, in colours and in words — even if those words weren’t what everyone wanted to hear. After arriving in Paris in the first week of July, Quinn had arranged a short meet with James Joyce in which the Ulysses author had grilled him about US Copyright protection and the Little Review affair. The court’s position on Ulysses in the United States hadn’t changed. In terms of US censorship laws, the book was still a hot potato. Publishing it there was out of the question. Quinn dryly explained to Joyce and his publisher, Sylvia Beach, the reality of what they were facing. Not that they needed telling. Only that April, the husband of the woman they had tasked with typing up a copy of the Ulysses manuscript had come across on his wife’s table, read a few pages and had been so incensed by what he’d read that he’d torn it up and burned it. [31] At the end of May, Beach had been telling her family and friends that in view of the huge success of her shop, she was planning to publish Ulysses herself: “the greatest book and author of the age.” The uproar that the trial had stirred back home was clearly something she was prepared to work with. Despite his support, her friend Ben W. Huebsch found himself unable to publish the book without the revisions required to pass the US censors. Beach’s frustration was balanced with a sense of heroic determination. In letters to friends back home she even mentioned the anecdote about the man at the British Embassy burning the copy of Joyce’s book, and at least one chapter of the original manuscript, that his wife was typing up. The man may have been Reverend Arthur Rocke Harrison who had served as assistant chaplain at the British Embassy in Paris and as chaplain in Pau before his move to the Embassy in Riga in the following year. After catching up with another of his curious assets — the surrealist poet, Henri-Pierre Roché in Fontainebleau and Sylvia Beach at the new premises of her bookstore in La rue de l’Odéon — Quinn followed Wilson to Italy and from there he sailed to England. [32] A year later, Quinn and Leslie would exchange a series of letters about the book, which just like Synge’s Playboy, would end up stoking Irish Nationalist tensions at one of the most politically sensitive times in the country’s history.

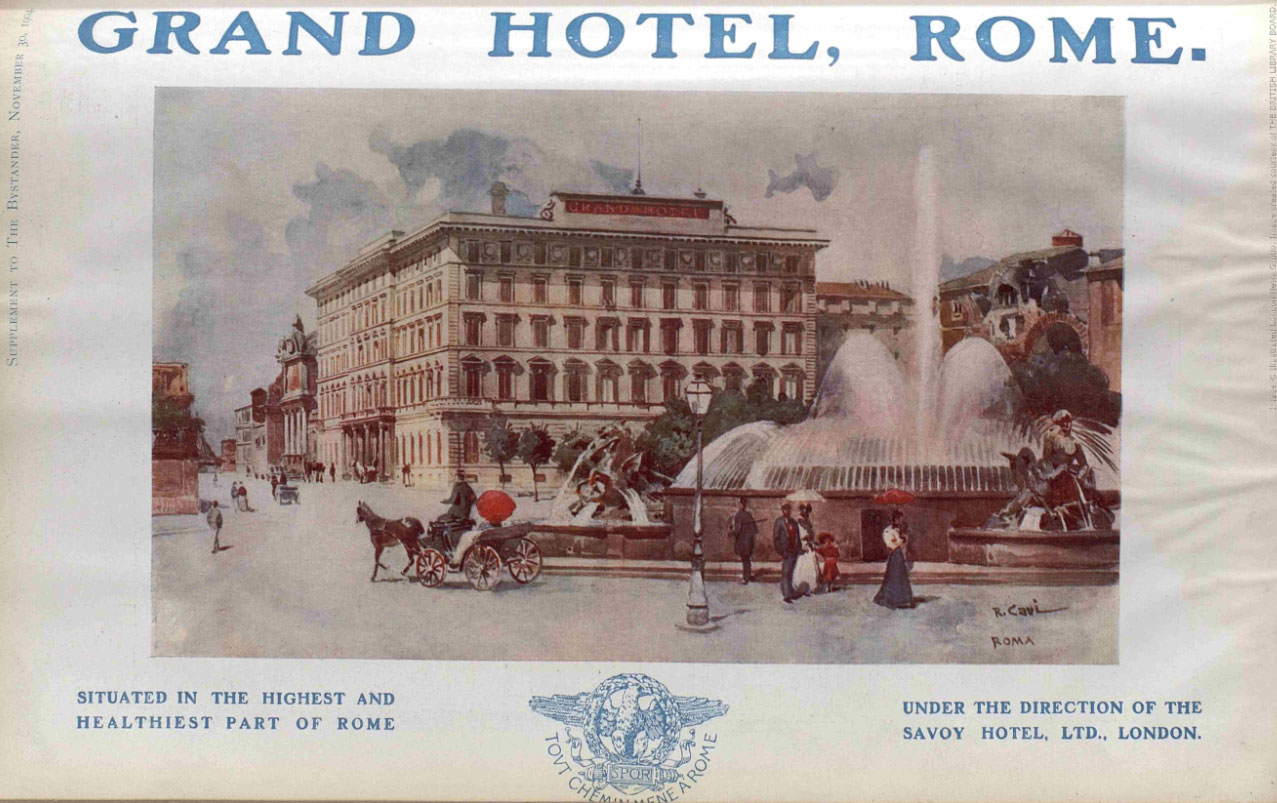

Trouble in Rome