I have an entry in my ‘Dairy Diary’ for 1984: Wednesday, July 18, 1984:

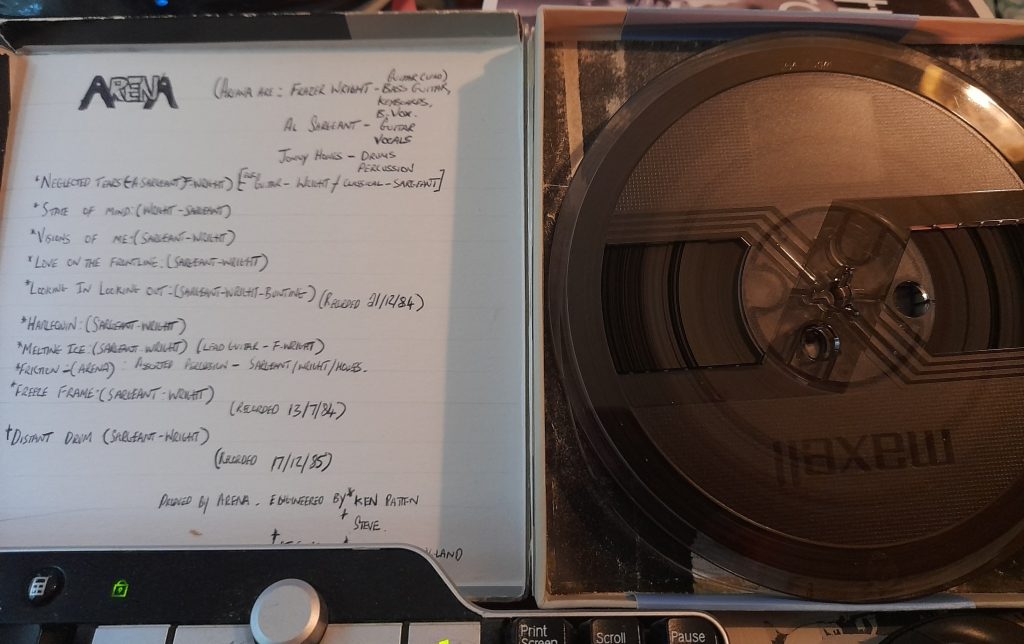

“Demo Day. Got up at 8.00am and had a drink, then took sarnies and guitar up to Frazer’s. We left for Sheffield about 9.00am. We got there about 9.40 and got properly started about 10.05. We did Freezeframe first, then Friction (1 take), then Melting Ice (2 takes) and then Harlequin (1 take). Then I did the vocals. Then we did percussion. We finished around 6.30pm. Got home and watched Monster Club with Vincent Price.”

Wednesday the 18th wasn’t just any old Wednesday in July. This was the day that our seven-month old band, Zero Option, headed to Ken Patten’s Studio Eletrophonique – an eight track recording studio in the unlikeliest of places, a semi-detached house on a council estate in Ballifield. We didn’t know it was called Studio Eletrophonique at that time, and it’s probably just as well we didn’t. It was just plain old ‘Ken’s studio’ to us, and that’s how it has stayed in my memory for the forty years that followed, filed somewhere between Ghostbusters, Smarties Mugs, picket lines and the Commodore 64. I was just 16 at the time and from my point of view we were standing at the threshold of fame. One day soon we were going to be as big as The Bluebells or even The Pinkees. We had arrived at Ken’s uPVC door with a spring in our step, some clingfilm-wrapped sarnies in our hands and stars in our eyes.

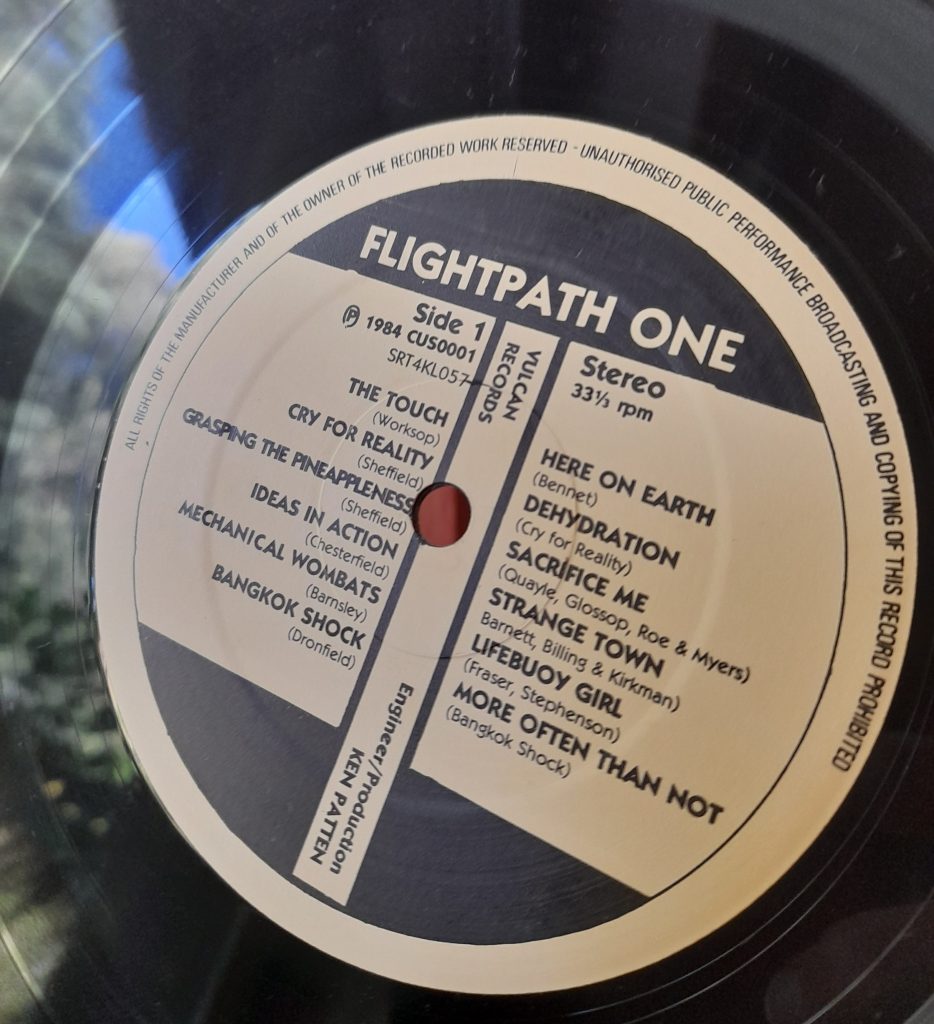

Fantastically, as a result of a surreal kink in the bodywork of pop-history, Ken’s studio is now the subject of a documentary film by Screen Yorkshire. We clearly weren’t the only scruffy youngsters turning up at Ken’s door dreaming of celebrity and armed with snacks, there had been others — many others — as this film proves beyond all doubt. The film, produced, directed and hosted by Sheffield musicians and filmmakers, James Leesley and James Taylor, features Jarvis Cocker and members of ABC and Human League recalling their own ‘demo days’ at Ken’s studio. The film is narrated by local hero, Sean Bean — yes, that’s Boromir from Lord of the Rings — and a book based on the film comes out next year.

My own memories of the place are still fairly vivid, if a little bit scrappy in parts. I remember walking through the front-door and being met by tiny yapping dogs under the less than precise management of Mrs Patten. I remember having to take our shoes off before we entered the living room, seeing a tin of Quality Street on the sideboard, and then the four of us being herded into a small extension built onto the side of the house with an expressionless Ken sat at his desk pressing some fresh tobacco into his pipe. “Alright lads,” he said without looking up. “We’ll get started in a minute. Just need to get this thing going and then I’ll take my tablets.” Without looking up Ken took a few routine puffs to fire up his pipe and reached for his cup of tea. “The tablets are for my heart. I’ll have to have some other tablets around 2.00 and we’ll need to stop for that.” Although I was probably not the only one questioning the wisdom of puffing on a pipe every two minutes if he had a bad ticker, I assumed that Ken had his doctor’s consent and I made no objection — stank though it did.

None of what we saw or heard here that day was conventional, but Ken didn’t care for much convention. The sight of the Quality Street tin on the sideboard had told us that. This was something you only saw at Christmas. In my neck of the woods it was tantamount to anarchy to a see a tin on the sideboard in summer. This made Ken a rebel. Behind that inpenetrable white uPVC door was a man sticking two fingers up at the usual protocols of surburban life. He was Che Guevara in slippers. Spartacus with a pipe and a Rowntree’s Toffee Penny.

One thing I do remember with clarity is that Ken was a man of few words, which was just as well as our drummer’s Dad was coming back at 7.00pm and was paying Ken £75.00 for 10 hours work. Time was money. Even if it wasn’t our money. The currency converter on the National Archives website tells me that £75 was about £200 in 1984. Probably what the Pitsmoor and Stannington miners were earning a year — when they weren’t striking, which was rather a lot in the 1980s. Whether it’s useful or not, the currency converter tells me that the buying power of £75 in the 1980s meant the drummer’s Dad could have got 180lbs of wool or four quarters of wheat for what he’d spent on the studio. If it was me I’d have probably traded in the time in the studio for the tin of Quality Street that Ken had on the side if Mrs Patten had tendered it, which she didn’t of course. It didn’t stop us trying to scab one though, but as protected as it was by the yapping Cerebus dogs, no one was able to get within five feet of it.

Ken didn’t ask how we got our name but we told him all the same, or at least a version of the story we could all vaguely agree on. It had been dreamt up by our former singer, Chris. He’d come to school back in January saying he had the name for the group. It was Zero Option. Being in the top stream at our local comp meant he’d been watching News at Ten the night before and someone — probably Alastair Burnet — had been talking about nuclear disarmament. President Reagan, on his way to some peace conference or other, had just made a speech in which he recommitted himself to getting rid of all of America’s nuclear weapons if Russia and everyone else in the world would do the same. Reagan didn’t just want to get rid of a few nuclear weapons — a baker’s dozen or whatever — he wanted to eliminate the whole bally lot. The newspapers were now telling us that Chernenko and Russia were refusing. Captain Sensible had warned the world of nuclear escalation a few years before. Not on Happy Talk, I hasten to add, but on The Russians Are Coming. I didn’t have the record but Chris and his older brother, Dave, probably did: “Lets arm ourselves tup to the teeth so I kill you and you kill me, let’s kill and rape, destroy it all, let’s kill ourselves and have a ball, let’s see there’s nothing left alive, make sure no-one can survive.” Within days, Chris’s brother Dave had written us a song expressing his regret that US-Russian relations were ruining negotiations on intermediate-range nuclear forces. Despite attempts by our bass player to brighten it up with some Mark King-style slap bass we passed it over in favour of a cover of Duran Duran’s Hungry Like The Wolf. Dave’s Crossfire, full of boisterous CND wisdom though it was, would never attract the girls.

When we told Ken about our name he was about as interested and cognisant as I was when Chris burst into the classroom back in January. “Nuclear weapons will be the end of us,” Ken philosophised and picked up another biscuit. He couldn’t have said a truer word, as the Barry Hines film Threads would prove at the end of the year. If Threads was right, and one of those bleedin’ things exploded over Fargate, we would have a brand new hole in the road in Sheffield by Christmas, and a whole new Band Aid record to go with it. Do they know its Christmas? More to the point, did Barry Hines know it was Christmas? And did the Russians love their children too? Sting wasn’t convinced, that was for sure, and he’d been a teacher once, so his grasp of the issue was likely to be immense.

At ten o’ clock we were ushered upstairs to one of the bedrooms to get down to business. It was another of Ken’s conversions. In one corner of the room was a CCTV camera, and Ken, still puffing on his pipe downstairs, was able to guide us through the recording process by way of our head gear. I remember our drummer being freaked by the electronic Simmons drum kit which made you play everything twice the speed and I remember everybody being a bit put out by playing the stuff without amps. Ken’s method of recording was a strictly ‘plug in and play affair’ — direct injection, or so so we were told. Our two guitars and keyboard were plugged directly into the mixing desk. The unhealthy trail of wires around our feet carried everything we played down to Ken’s recording kingdom downstairs. It wasn’t technology that made this happen, it was magic. Is this what it was like to be famous? asked one of us, does being famous mean no amps? In all likelihood, someone replied. But at least we’d have our own tin of Quality Street, I added.

We ran through our numbers pretty swiftly and then Ken did his best to stretch it out till seven o’ clock by telling us all about his weird and wacky inventions that he’d done for less than a pound and his stories about ABC having only one string on their bass when they came to his house a few years earlier. At 7.00pm our drummer’s Dad came as planned and paid Ken his £75.00. The rest they say is history, even if there isn’t a nice blue plaque on his house to prove it. Before the year was out, Zero Option had disbanded, not as a result of artistic differences, as is usually the case, but because the yougest member of the band had his O Levels coming up and the member with the synth was now desperate to join a ska band. As if to prove how incestuous life is in Sheffield, I eventually ‘understudied’ in a band whose drummer, Rod, once banged his sticks for Sheffield’s Clock DVA, whose leader, Adi Newton, features in the film on Patten.

“Studio Electrophonique survived on the outer ring road of art,” growls an appreciative Sean Bean at the end of the film, and it describes the whole Ken experience just beautifully. Ken survived on the outer ring road of art and Zero Option stalled at the pedestrian crossing of celebrity. In spite of that, we learned quite a lot from Ken. He didn’t just provide a room to record audio and the space to dream, you turned up at his door with your Korg or your Casio, your Vox guitar or your Westone bass and Ken provided all the clearance you needed to do things a little bit differently.

Pour me a tea and pass me another biscuit, I feel a toast coming on: ‘This is to Ken, who let us tweak the dials in our favour at life’s great mixing desk.’