The most deadly deep fake in history. Despite being exposed as a fake in 1921, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion which tells of a secret Jewish plot to destroy and take over the world went on to play its part in the suffering and brutal murder of over six million men, women and children as part of Hitler’s ‘Final Solution’. This is the story of the part played by a British post-war pressure group, angling for war with Lenin’s Bolsheviks, in its revival and distribution in print.

According to Robert Hobart Cust it was Temporary Major Edward G.G. Burdon who assisted former Royal Navy pilot, George Shanks with his post-war translation of The Jewish Peril — the first-ever British imprint of the bizarre and malicious forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, originally published in Russia in 1905. An account of the fake’s revival can be read in Professor Colin Holmes’ ground-breaking book, Anti-Semitism in British Society 1876-1839, which not only provides a detailed exploration of anti-Semitic thought and its expression during the late Victorian and early Edwardian period, but also dismantles some of the stereotypes and misconceptions that many of us still have about the fascists of post-war Britain. In his book, Holmes explains how Burdon had personally showed an early draft of the notorious pamphlet to H.A. Gywnne, Editor of The Morning Post, in November 1919. This claim was made in a letter that Cust had written to Gywnne in which the respected art historian was keen to correct him on a number of minor issues relating to a review of the pamphlet his newspaper had published in February 1920.

In subsequent attempts to unravel the mystery, Burdon has been either dismissed as figment of Cust’s imagination or quickly glossed over, but in doing so historians have neglected a critical part of the narrative, as Burdon had played a key role in helping manage Britain’s often confusing abundance of Anglo-Russian (and anti-Bolshevik) pressure groups in the immediate aftermath of the February Revolution in Russia.

Browsing again through Holmes’s book some twenty years after I had read it originally, I am struck by just how little attention has been paid to Burdon over the years. Holmes is not at fault in this. In another account of the story, Gisela C. Lebzelter similarly refuses to be side-tracked by the biographies of minor characters in the evolution of British Fascism — a reasonable enough decision in the context of building a tight chronological narrative about the history of a movement, but an approach that becomes ever more inadequate when dealing with personal motivations of individual threads in a web of broader intrigues. What both writers agree on, however, is that the information that Robert Hobart Cust had on Shanks had come to him via Burdon, a “most accomplished linguist”. Burdon is said to have shown him a draft copy of their work in November 1919, and requested his friend’s assistance in finding a publisher, for which Cust duly obliged. Beyond that there’s been nothing at all. In the hundred and one years that have now elapsed since the work was first published, no one has attempted to dig any deeper. A few words of explanation have occasionally been expressed about Shanks, in which he is invariably presented as a vexatious refugee without a penny to his name and only the weariest of old axes to grind, but not a single attempt has been made to understand why Major Burdon used his considerable language skills to assist Shanks in this intensely malicious project. However, in revisiting the life of Burdon it now possible to shed some light on some of the dark and invisible forces that may well have been at work behind the scenes when the pair set about preparing the first-ever English translation of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. In fact, Edward G.G. Burdon may eventually prove every bit as important Shanks himself, perhaps more so, as the Association that had been paying Burdon as Paid Secretary since 1917 featured some of the most influential men in Anglo-Russian Relations, as well as some of Britain’s most pernicious racists and anti-Bolsheviks during the post-revolutionary period.

Contrary to the narrative currently favoured by modern British historians, discoveries I have made recently suggest that Edward G.G. Burdon and George Shanks may not have been acting as part of some acrimonious fringe-fascist group, letting off steam about Britain’s Jews for their own simple sadistic pleasure, but advancing the fiercely reactionary policies of a powerful government lobby that inhabited a tight political circle in Edwardian Britain. You can read more about Shanks here, but for now I would like to focus our attention on Burdon.

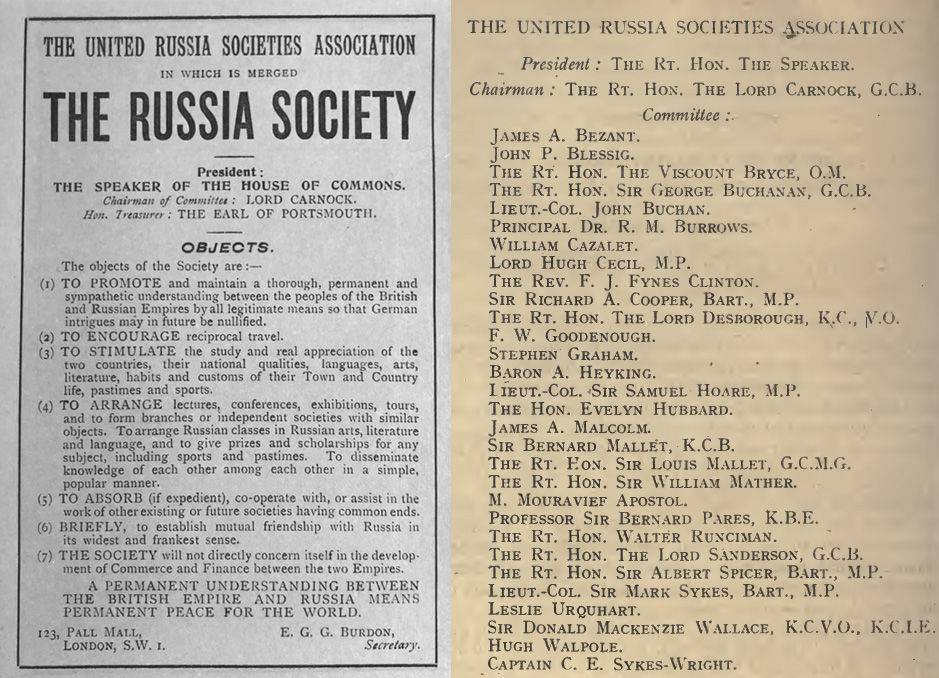

United Russia Societies Association

The group that Burdon was appointed to represent as ‘Paid Secretary’ just two years before the pair commenced work on the The Jewish Peril was the United Russia Societies Association. Launched with little or no public fanfare in February 1918, U.R.S.A as it became known, had been set the almost impossible task of uniting the various Anglo-Russian interest groups that had evolved since Tsarist Russia had joined the allies in the war with Germany. The association was, in actual fact, a more all-embracing version of The Russia Society, set-up to support the entry of Imperial Russia on the side of Britain and her allies in the first few years of the war. This was an awkward moment for Britain whose default position, rather like that of America, had been to publically condemn the draconian abuses meted out as a matter of course by Tsar Nicholas on his people. Perceived rather negatively as the land of “slaves and tyranny” it was thought that the average Brit viewed our first-time alliance with Russia — “our gallant new friend” — as a difficult pill to swallow. Britain at this time had a very distinct yet outdated image of Russia; it was the land of serfs and conscripted peasants, either toiling in the fields or marching to certain death in the battlefields of Turkey and the Crimea. The general perception among most Brits was that the country was tyrannical, ultra-orthodox, un-modernized and stubbornly un-modernizable. The Tsar was seen as ruling absolutely, and his entourage of ministers and advisers were not unreasonably perceived as being absolutely corrupt.

Drawing from an enviable pool of respected academics, former diplomats, War Cabinet advisors and religious leaders, U.R.S.A did its best to change those old perceptions and re-draft this Colossus of the North as a kindred cultural spirit which was nothing at all like the “mischievous and distorted” image its neighbour Germany had been promoting for all those years. We just needed to adjust our reading of Russia, that’s all. It was all too easy to compare the mighty Empire of Snow to Britain or America, we needed to understand it on its own terms — not in comparison to our own Constitutional history, which had been steadily maturing for the best part of three hundred years, but to the more Liberal path that our Russian friends had been taking since establishing its first democratically elected assembly in 1905, the State Duma. As undesirable as it was, Russian autocracy, it was now being reasoned, was “the only possible alternative to anarchy” and that the Russian people “did not want and would not understand, any other form of government”. The people really to blame were the country’s rivals. Russia had been our friend all along. All previous attempts to reconcile the two nations in the past had failed, it was now being said, as a result of “German intrigues.” [i]. Every attempt was now being made to mobilise public opinion in favour of Imperial Russia, something that had never been done before. The British public were being asked to appreciate that only thing that had ever come between the two empires in the last few hundred years had been the ‘Bosche’. And if the Brits should need any further proof, they had only to look at the Kings themselves, George V and Nicholas II, who bore an extraordinary likeness to each other (and would often dress similarly in front of the press just to ram the point home).

In a rather peculiar twist, it appears that the man who had appointed Burdon to the position of ‘Paid Secretary’ to the new association was none other than, James Aratoon Malcolm [ii] — the founder of its predecessor The Russia Society and a long time confidante of the Sassoon dynasty. According to statements made by Malcolm in the 1940s, he was also one of Britain’s earliest and most passionate champions of a Jewish National Home in Palestine, whose suggestions were taken up at the very highest levels of the British War Cabinet. [iii] Whilst we will explore the various details of Burdon’s Association and Malcolm’s grandiose claims in a separate article, here is a summary of what we do know about the early life of Burdon and the United Russia Societies Association he joined in 1917.

The Upper Ten Thousand

Burdon wasn’t just your average Brit. He was part of England’s highly regarded ‘Squirearchy’, taking practically all his income from those who lived on his land and the various farming activities performed thereon. The best insight we have into Burdon’s relatively advantaged status within the distinguished upper strata of English civil society is revealed in Edward Walford’s Royal Manual of the Titled and Untitled Aristocracy of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, an ambitious tome of some 1100 pages that identifies all the “highest families of the three kingdoms”, or, in common parlance, a ‘Dictionary of the Upper Ten Thousand’, republished, not unsurprisingly, by Spottiswoode & Company in 1909. Skip to page 156 of the manual and you will find an entry that reads: “Edward Griffiths George Burdon, Capt. and Hon. Major 3rd Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers; b.1872, New Court, Lugwardine, Herefordshire”. His father was George Burdon and his mother, Frances Jane Griffiths of Heddon House, Northumberland. After the death of George, his brother, the Reverend Richard Burdon, the eldest son of Edward’s grandfather George Burdon Esq, was declared the new Lord of the Manor. Here he would spend the remaining years of his life dolling out fines, and settling local disputes as Justice of the Peace and Deputy Lieutenant of Northumberland. [v]

This ancient Northumbrian family could boast several baronets including John Burdon Sanderson (the respected physiologist) and the First Viscount Haldane, Richard Burdon Haldane, the British Secretary of State for War from 1905 to 1912.[vi] Despite his birthrights in Northumberland and Herefordshire, Edward Griffiths George Burdon was baptised in Torquay before the family took up residence at Batheaston Villa in the village of Bathampton in Bath. The surroundings may have been rather more provincial compared with Heddon House, but Edward’s father, who describes himself as an “living on own means” in a census entry of this period, could nonetheless count the Duke and Duchess of Beauford and former Ambassador to Russia, the Marquess of Clanricarde among his peers during his regular visits to London.[vii] An additional source of income for the family were the dividends (interest) returned on Government ‘consols’ — loans made to the government in support of the state-owned infrastructure propping-up the British Empire.

As small as it was, Burdon’s home in Bathampton wasn’t without its charm. The 18th Century novelist, Horace Walpole writing to George Montague Esquire in 1766, described Batheaston Villas as a “small new-built house with a bow window, directly opposite to which the Avon falls in a wide cascade, a church behind it in a vale, into which two mountains descend, leaving an opening into the distant country. The garden is little but pretty, and watered down with several small rivulets among the bushes. Meadows fall down to the road; and above, the garden is terminated by another view of the river, the city and the mountains.” [viii] Lying two miles from Bath, this “diminutive principality, with large pretensions” was the former home of Lady Anna Riggs Miller whose poetry and literature salons in its lavishly Italianate grounds provided Walpole with some of the inspiration for Britain’s very first Gothic novel ‘The Castle of Otranto’. Surrounded on virtually all sides by high walls and lofty, ancient woodland and cut-off from the main part of the village to the south by an almost infinite, winding driveway, the Villa would have been very well protected from prying eyes.

The Villa itself was a sophisticated fantasy, reflecting the deep admiration that Lady Miller had for her spiritual home of Italy, whose lush, exotic lands she had spent years of her life exploring. On her return to England in the 1760s, the “Arcadian patroness” had built Batheaston — part-fairy-tale, part-folly, part-Palazzo. The Temple of the Apollo, the God of Truth and Prophecy that stood in its gardens at the time Miller built the property, can be seen in its garden still, proving that its follies were nothing if not permanent. If Rupert Brooke had attended one of the many poetry salons that Lady Miller hosted in its gardens, he might very well have revised the most famous of his verses: The rich earth and rich dust concealed some corner of a field in Bath that was forever Italy. Some two hundred years later during the counter-culture revolution of the late 1960s these same eccentricities would transform Batheaston Villa into a free-spirited hippy commune with its own dedicated Maharishi. [ix]

During the Burdon family’s time at Batheaston, Edward’s father George was, in all likelihood, surviving on a relatively generous allowance, making any attempt to explore his employment or business dealings a difficult if not futile undertaking. It’s likely that that whatever his family wanted for in life, he was given. One thing we do know, however, is that the family was Catholic and may well have possessed some personal or business links to France and Germany. We know this because, in a copy of the Catholic journal The Tablet in October 1889, Edward’s mother Frances Burdon had placed a small ad. She was looking for a French Governess, well-recommended, of ‘Brevet’ stock with good German.[x] Given that these languages were fairly dominant in the civil service and military professions, another plausible explanation is that the family were already busy planning the children’s futures. In 1892, the Batheaston Villa was put up for sale where it was picked up by the Reverend Clement Reginald Tollemache and his wife Frances. Their daughters Grace and Aethel would subsequently become explosive branch secretaries of Pankhurst’s Suffragettes, both sisters eventually being arrested in 1914 on charges relating to the Defence of the Realm Act after protesting at Buckingham Palace.[xi]

After serving with distinction in the Second Boer War (1899-1902) Edward Burdon was awarded the rank of Major and given leadership of Northumberland’s Special reserve at the outbreak of the war with Germany in 1914. [xii] However, an injury the following year saw him placed on other duties and he was duly downgraded to Temporary Major. I have yet to view his full military service record but it does seem to be available at the War Office. [xiii] How Burdon made the transition from decorated field veteran to Secretary of the United Russia Societies Association isn’t yet clear, but if the letter from Robert Hobart Cust to H.A. Gwynne is anything to go by, it may well have been on account of his competence as a Russian linguist, although where he picked up such skills is something I have yet to fathom. Relevant or not, it’s probably worth noting that Burdon’s appointment as Secretary at the United Russia Societies Association (U.R.S.A) coincided with another important merger, when the War Propaganda Bureau and the Neutral Press Committee combined to form the Department of Information in February 1917 — an indication perhaps of changes in the direction the war was taking, and Britain’s increasingly cosy relationship with a rapidly evolving Russia.

Nourishing Falsehoods for Popular Consumption

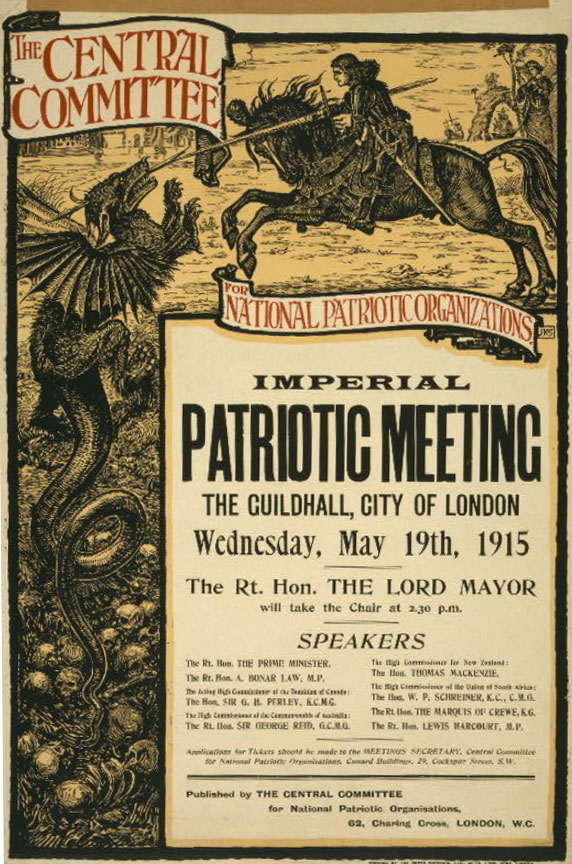

According to the minutes of the first meeting of the group, the United Russia Societies Association that had recruited Burdon in February 1917 had been formed under Malcolm just one month before at the invitation of Harry Cust, the first cousin of Burdon’s close friend, Robert Hobart Cust whose letters to H.A. Gwynne would be the first to divulge the secret of his collaboration with George Shanks on The Protocols forgery (The Jewish Peril). [iv]. As Chairman of the Central Committee for the National Propaganda Organisation, Harry Cust had been among the first to recognize the considerable part being played by specially prepared propaganda in the war efforts of enemy Germany. Responding to this, Cust launched the C.N.P.O in August 1914 with British Prime Minister H.H. Asquith dutifully sworn-in as Honorary Secretary. A statement published on page five of the Pall Mall Gazette on October 9 1914 in support of the group’s launch reads: “The German Government it may be noted has recognized the importance of the same function by preparing a first-rate service of nourishing falsehoods for popular consumption, and making truth contraband of war”. If it was ‘falsehoods’ Britain needed most in its hour of need, Cust and his friends were about to provide them in droves.

Cust’s Central Committee for the National Propaganda Organisation and the Neutral Press Committee, set-up by the Home Office the following month to concentrate efforts in countries outside the British Empire, had arisen as a result of a lack of coordination among the various groups attempting to support the war effort on British soil. It was inevitable that similar calls for the centralisation of activities in support of Imperial Russia would be made some three years later when the cracks in the Tsar’s autocracy would see the resolve of the Triple Alliance begin to fall apart; the upshot of which was the formation of U.R.S.A.

James A. Malcolm

As skilled and influential propagandists during the war the men that made up U.R.S.A’s executive committee also had firm ties to British Military Intelligence, making the scope for possible intrigue especially broad and complex. But in order to understand both the need for the Association, and the need for appointing Burdon, we need to take a step back and take a look at the man whose last act as Honorary Secretary of The Russia Society was to appoint Burdon as ‘Paid Secretary’ of the new amalgamated alliance — James Aratoon Malcolm. [xx]

A statement made to the British Press by Malcolm in February 1917 tells us that he will shortly retire as Honorary Secretary to The Russia Society, a group he had founded some two years previously, and take up a new position on the committee of the new parent association. His first task at the new association would be to appoint a paid secretary at the group’s temporary offices at 123 Pall Mall. A public notice published in The Times of London on February 21st 1917 reads:

It has been felt for some time that it would be an advantage if the several organizations in London having for their object the promotion of friendly relations with Russia were consolidated. Owing to the formation in Petrograd of the Anglo-Russian Society under the Chairmanship of the President of the Russian Duma and the auspices of the British Ambassador, steps have been taken to bring this about, and it largely due to the good offices of Sir George Buchanan and the Speaker of the House of Commons (President of the Russia Society) that an agreement has been reached to amalgamate that society, the Anglo-Russian Friendship Society and the Anglo-Russian Committee, with the cooperation of the Russia Company. The speaker has suggested the new title “The United Russia Societies Association”, and a meeting will be held at the Speaker’s House on March 2 at 4.00pm, to pass the necessary resolutions for bringing about this fusion.

Mr James A. Malcolm, the founder of the Russia Society and its honorary secretary, will retire from his office. He has, however, consented to join the Committee of the new association, which will appoint a paid secretary and have temporary offices at 123 Pal Mall, London, S.W .[xiv]

The “President of the Russian Duma” who was overseeing the amalgamation of these societies back in his home country of Russia was the deeply religious Liberal and conviction politician, Mikhail Rodzianko, the fifth Chairman of Ruusia’s State Duma. It’s not always easy to find a modern-day equivalent, but in view of his noble birth and his ruthless, razor-sharp political timing, Rodzianko might well be regarded today as a cross between Britain’s Jacob Rees-Mogg (a meddlesome minor aristocrat) and a born-again Jonathan Aitken (a resourceful Archangel).[xv] Little more than three weeks after this notice was published, Rodzianko would become a leading figure in the history-changing events that would culminate in the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II on March 15.[xvi]

There are a number of things I’d like to draw your attention to before moving on. The first is the revival and cooperation of the practically defunct Anglo-Russia trading body, The Russia Company, whose senior members, certainly in previous years, included the grandfather of Burdon’s co-author, George Shanks. Founded in the 1500s as a means of exploiting and expanding the Caspian trading routes between Persia and Southern Russia, The Russia Company had maintained an impressive monopoly on English-Russian trade until the early 1700s when it finally lost many of its remaining privileges under Peter the Great. Until recently the Society’s fortunes had dwindled to such an extent that it could no longer boast any real influence, its activities confined to strictly charitable endeavours, providing outreach, maintaining churches in the English Colonies. By 1915, however, things were looking up. The Russia Company had been founded for the purpose of exploiting trade between Persia and Russia, now it was being revived on that same principle. As news began to emerge of allied control of the Caspian, traders in Moscow announced plans for a new Anglo-Russian shipping bank. As Malcolm had built his reputation as the world’s foremost Caspian trader, his sudden ubiquity in Near East war efforts was interesting to say the least.

The second point worthy of mention is that Malcolm was stepping down as Honorary Secretary of The Russia Society, which was little more than an administrative role (taking minutes, dealing with correspondence, hiring venues) and taking a more hands-on position on the Executive Committee of the new association, meaning less paperwork and more influence on decision-making and strategic planning. It was an unusual move in the circumstances. Unlike other members of the committee, Burdon’s chief, James A. Malcolm couldn’t really boast any formally recognised status. He wasn’t a Lord, he wasn’t a leading academic, he wasn’t an elected Member of Parliament and he didn’t have a commission with either the Ministry of War or the Ministry of Information. There was another thing too. With the possible exception of Russian Consul, Baron Alfons Heyking and Chamberlain to the Tsar, Vladimir Mouravieff-Apostol, Malcolm was also the only member of the U.R.S.A committee not to have been born in Britain. So if you are wondering why he is there at all, you’re not alone.

In a follow-up advert placed by the associations’ chairman, Lord Carnock in The Spectator and The Times in March 1917, it becomes clear that the man given the role of ‘Paid Secretary’ at the new parent association was Protocols translator, Edward George Griffiths Burdon:

To the Editor of the Times

Sir, —I should be obliged if you would permit me to bring to the notice of the public, through your columns, that the United Russia Societies Association, of which the Speaker of the House of Commons is President, would welcome applications for membership. The subscription for members is 10s. per annum, but further information would be given, if desired, by the secretary of the association—Major Burdon, 123 Pall Mall, S.W 1. —who will receive contributions.[xvii]

The impact that Burdon’s appointment would have on The Protocols narrative shouldn’t be underestimated. What knowledge the other members had of Burdon’s involvement in the translation and dissemination of The Jewish Peril pamphlet may not be known, but it’s almost certain that his work as coordinator for U.R.S.A had played no small part in his encounter with George Shanks, his introduction to the Russian forgery, and the essential part it would come to play in Britain’s propaganda campaign against the Bolsheviks, at this time regarded as the ‘Jewish Menace’. Incidentally, the man who had been tasked with drawing up a syllabus for an elementary and advanced language school for both The Russia Society and its successor, U.R.S.A at 37 Norfolk Street, The Strand was Shanks’ uncle, Aylmer Maude. [xviii] The Norfolk Street address is interesting as Britain’s Ministry of Information, first under Charles Masterman and later under U.R.S.A’s John Buchan, had requisitioned several properties on this street for the duration of the war.

Many of the individuals appointed to the executive board of U.R.S.A had formed the backbone of the Anglo-Russian Bureau, the propaganda and political intelligence-led unit that had worked so closely and so diligently with Military Intelligence in Petrograd during the war. Many more of them, including Sir George Buchanan (British Ambassador to Russia), Aylmer Maude, Archibald Sinclair, Samuel Hoare, John Buchan and Hugh Walpole [xix] would also go on to play vital roles in the aggressive pro-Intervention campaign launched by Britain in the immediate aftermath of the Second Revolution of October 1917, a revolution that was being blamed, somewhat predictably, on the relatively small number of Jewish Maximalists and Internationalists seizing control of Russia under the banner of the Bolsheviks.

Within a year of U.R.S.A’s formation, the British War Cabinet requested that a White Paper be drawn up that would give a blow by blow account of the abuses being carried out by the new ruling power in Russia. If Britain was to go ‘all out’ with Lenin’s Bolsheviks after the Armistice had been declared, then its Coalition Government would need a firm moral basis to convince both its public and its Prime Minister to enter another war.

The report, which would eventually become known as the Russia No.1 White Paper (April 1919) — and more informally as the ‘Bolshevik Atrocity Blue Book’ — drew up a catalogue of abuses that portrayed Lenin’s upstart Bolsheviks as power-hungry Jewish radicals out to unleash their venom and frustration on the capitalist world at large. The war with Germany had officially ended and decisions would need to be made about continuing British efforts on the North Western front. For the White Russian generals leading the counter-revolution against the Bolsheviks, time was running out, and allied support was fading. The pressure to mobilise British opinion moved across to Britain’s press.

The Daily Chronicle, whose commentaries on the latest developments in Russia were being peddled by Intelligence and propaganda man, Harold Williams at this time, was the first to draw attention to the fact (inaccurately, it has to be said) that practically all of the main Bolshevik officials were Jewish (and just quite possibly Lenin too). The magazine Reality: Searchlight on Germany, the official organ of the National War Aims Committee chaired by Churchill’s cousin (and Shanks’ employer at the Chief Whips Office) Freddie Guest, repeated the claims just one week later on November 17th (Issue 97, p.4). By the time that the Russia No.1 report was published, Sir Mansfeldt Findlay chief of the Legation in Christiana was able to provide all the clarity and sense of moral purpose that was needed to move things forward. In a telegraphic to the British Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour dated September 17th 1918, Findlay had written:

“I consider that the immediate suppression of Bolshevism is the greatest issue now before the world, not even excluding the war which is still raging, and unless, as above stated, Bolshevism is nipped in the bud immediately, it is bound to spread in one form or another over Europe and the whole world, as it is organised and worked by Jews who have no nationality, and whose one object is to destroy for their own ends the existing order of things. The only manner in which this danger could be averted would be collective action on the part of all Powers.”

— Russia No.1 White Paper (April 1919) A Collection of Reports on Bolshevism in Russia, p.6

By the time that Burdon and Shanks had published The Jewish Peril in January 1920, the most passionate anti-Communist of them all, Sir Winston Churchill was talking of ‘possible new military commitments’ to stave-off the ‘Bolshevik Peril’ in the Near East. Britain had made the decision to withdraw from North Russia in October 1919. America had followed suit. But Britain’s new bulldog War Secretary was not prepared to give up so easily.

Churchill had first made use of the word ‘peril’ in a cautionary address in Sunderland in the first week of January 1920. Explaining the plans of the Bolsheviks — the “enemies of civilisation” to the crowd in the Spen Valley, Churchill roared that they were “out to destroy capital” and “sought to control monopolies” of the world: “they seek to exterminate every form of religious belief that had given comfort and inspiration to the soul of man. They believe in the International Soviet of the Russian and Polish Jew”, he went on.

As if matters weren’t fragile enough, Churchill followed up his battle-cries in Sunderland with plans to channel Britain’s vast reserves of casual anti-Semitism into the path of the brand new Bolshevik threat. The plan would achieve critical mass with an article that Winston would prepare for the Illustrated Sunday Herald: ‘Zionism versus Bolshevism’. In a generous two page spread published on February 8th 1920 Britain’s Secretary of State for War, drew-up a rambling, ham-fisted case for a establishing a Jewish National Home in Palestine, the only possible solution that he could see to the spreading Bolshevik menace whom he summarised rather grotesquely as “the International Jews”. If there is one single piece of evidence to suggest that George Shanks and Major Edward G.G. Burdon had been actively colluding with the pro-Interventionist lobby gaining mass at that time under U.R.S.A, it is probably this one article. Firstly, the article’s timing with The Protocols translation is nothing short of miraculous. Shanks and Burdon’s Jewish Peril received its first review on page eight of the Westminster Gazette on February 9th 1920. The sabre-rattling article by Winston Churchill was published in the Illustrated Sunday Herald just 24-hours before.

Anyone who has managed to preserve an otherwise high regard for the cantankerous wartime Prime Minister may be disturbed to learn that this worryingly inflammatory article draws substantially on the preposterous claims being made in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion; namely that the Jewish Internationalists under their leader, Vladimir Lenin were engaged in a diabolical plot to dominate the world and destroy the established order of things. Any attempt to square this off neatly with Winston’s stunning and very sincere triumph over Nazi Germany in World War II is an almost impossible task. In fact for most Brits, if not for most of our allies, past and present, the article won’t make a fat lot of sense. More often than not the problem will be dismissed fairly involuntarily as the ambiguous actions of a very complex man and a very inconvenient truth. In actual fact, it was neither that inconvenient nor that complex. Churchill had embraced Zionism as a colonial and economic necessity. The real problem, if there is one, is not that he was anti-Semitic. Like most in his class, he was. The problem was that he was embracing Zionism at the same time he was expressing sympathy for conspiracy theory of Jewish Bolshevism. There was no subsequent epiphany that put a redeeming wedge of virtue between this and his later actions. The image we have of Winston wrestling Adolf to the floor and plunging the sword of righteousness into the heart of his evil empire, whilst not a myth entirely, has been rather crude and one dimensional. Winston was more like Cerberus, the multi-headed dog guarding the gates of the Empire from his twin Cerberus rival opening the gates of his. Whilst their perception of the “International Soviet of the Russian and Polish Jew” may have been similar, their politics and their loyalties couldn’t have been further apart.

Perhaps the fairest way viewing the article was that it was a knee-jerk reaction, conceived in the midst of totally unparalleled events rattling along at a furious pace. It was weak, opportunist effort from a complex and unpredictable character attempting to solve two problems with one instrument as fast as politically possible. No matter how much we may judge him by modern standards, Churchill could never be described as closet-fascist.

It’s not a pretty read on any level. Even by the standards of the day, this was a deeply offensive appeal, worded to draw as much venom as possible to the fangs of an anxious, exhausted public, reluctant to do battle with a big new threat from the continent. In his rush to make his point, Churchill literally lumps together “malevolent” Jews like Karl Marx, Leon Trotsky, Bela Kun, Rosa Luxembourg and Emma Goldman for preaching the “gospel of the antichrist”. He also heaps no small amount of praise on fascist conspiracy theorist, Nesta Webster who had “so ably shown” that Jews had been the mainspring of “every subversive movement during the Nineteenth Century”. His worst fear was coming true: Jews were rising to prominence in these movements and seizing control. The exception to all this was Zionism which, as far as Churchill was concerned, presented a “more commanding” option for building Jewish national identity. Zionism was moreover, already becoming a factor “in the political convulsions in Russia, as a powerful competing influence to Bolshevism”. The struggle between the Zionist and Bolshevik Jews, Churchill enthused, was “little less than a struggle for the soul of the Jewish people”. Establishing a Jewish home in Palestine would “vindicate the honour of the Jewish name”. It was a simple proposition the War Secretary was putting forward to the Jews of Britain: you were either with us or against us.

A Mysterious Box of Letters … to be Sent ‘Unopened’

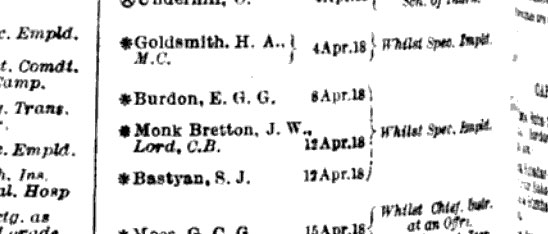

What became of Edward Burdon after his appointment to Malcolm’s U.R.S.A is a little vague, as his next appearance in the press comes in the Supplement to the London Gazette on August 21st 1919, when it is announced that Temporary Major Edward Griffiths George Burdon (Army Special List) had been awarded an O.B.E. As the ‘Special List’ is a reference to officers who may have had ordnance, linguistic or intelligence skills, it may be reasonable to suppose that the award was given for his contributions to translation, either as part of communications from the White Russian command in Omsk, or part of signals or intelligence duties. According to the British Army lists, published monthly during the war, Burdon was promoted to the Special Lists on April 8th 1918 alongside British Liberal Politician and former attaché in Constantinople, Lord John W. Monk Bretton, whose reports on the Armenian Massacres of the late 1890s are likely to have found favour with James Aratoon Malcolm and Britain’s war efforts in Asia and the Near East. Given that Malcolm, now serving as London representative to the National Delegation for Armenia was responsible for recruiting Burdon, it’s entirely possible that there is some as yet unknown connection between the appointment of Burdon to the desk at U.R.S.A and the pair’s joint appearance on the ‘Special Lists’.[xxi] According to file at the British Admiralty, Monk Bretton had spent the previous years of the war attached to Naval Intelligence, using his code breaking skills in the legendary Room 40 under Rear-Admiral Sir W. Reginald Hall.[xxii]

After the war Burdon was to inherit and then quickly resell the family’s Heddon House Estate in Northumberland. After this, he appears to have lived mostly in Pau in South Western France, a region close to the Spanish borders. The French Press records his various residencies at hotels in and around Biarritz. Interestingly his final home at Villa Belle Rive in Trescoey was also the registered address of Radio Luxembourg pioneer and journalist, Louis Merlin, appointed head of propaganda at the Havas news and broadcasting agency during the Liberation of France from the Nazis. This may suggest a link between Merlin and his old friend George Shanks, both of whom were associated with the founding of Radio Normandy and Radio Luxembourg in the mid-to-late 1930s.[xxiii]

His next appearance is a little more bizarre. In March 1937, it emerged that Burdon had died and left an estate of over £100,000 in his will, £5,000 of which was to go to his old friend, George Shanks. The details were duly reported in Sussex newspaper, The Kington Times. So peculiar are the conditions that Burdon attaches, that they are rather worth quoting in full:

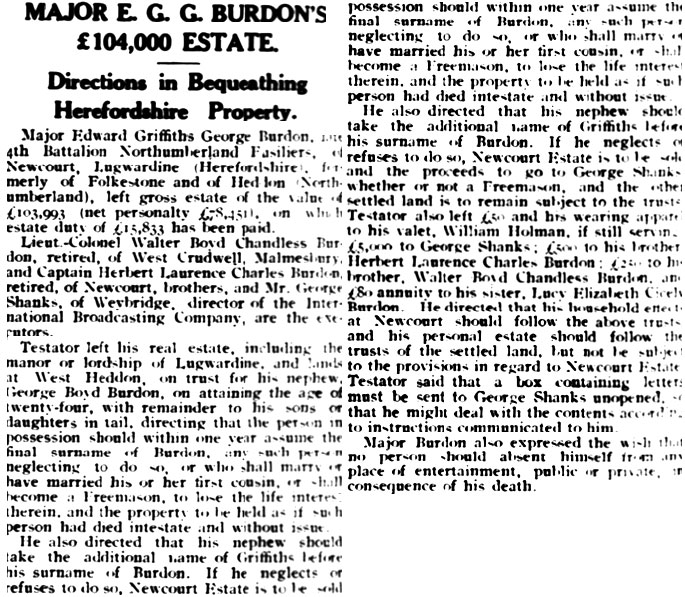

Major Edward Griffiths George Burdon, late 4th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers, of Lugwardine (Herefordshire), formerly of Folestone and of Heddon (Northumberland), left gross estate of the value of £103,993, on which estate duty of £15,833 has been paid.

Lieutenant-Colonel Walter Boyd Chadless Burdon, retired, of West Crudwell, Malmesbury and Captain Herbert Laurence Charles Burdon, retired, of Newcourt, brothers, and Mr George Shanks of Weybridge, director of the International [xxiv]Broadcasting Company, are the executors.

Testator left his real estate, including the manor or lordship of Lugwardine, and lands at West Heddon, on trust for his nephew George Boyd Burdon, on attaining the age of twenty-four, with remainder to his sons or daughters in tail, directing that the person in possession should within one year assume the final name of Burdon, any such person neglecting to do so, or who shall marry or have married his first cousin, or shall become a Freemason, to lose the life interest therein, and the property to be held as if such person had died intestate and without issue.

He also directed that his nephew should take the additional name Griffiths before the surname of Burdon. If he neglects or refuses to do so, Newcourt Estate is to be sold and the proceeds to go to George Shanks, whether or not a Freemason, and the other settled land is to remain subject to the trusts.

Testator said that a box containing letters must be sent to George Shanks unopened, so that he might deal with the contents according to instructions communicated to him.[xxv]

A mysterious box of letters must be sent “unopened” to his old pal, George Shanks? It was a move worthy of the best Agatha Christie novel. What on earth could have been inside the box and what was so top secret that they had to remain unopened? It’s a career that starts with a mystery, and ends with a mystery. What could be more fitting?

Article contributed by Alan Sargeant

Notes

[i] The New Russia Society, Dundee Courier, Dundee Courier May 15 1915, p.4; The Russia Society, The Scotsman January 25 1915, p.11

[ii] The Russian Revolution and Who’s Who in Russia, Zinovy N. Preev, TJ. Bale & Danielsson, May 1917, Anglo-Russian Friendship, The Times of London, February 21 1917, p.9

[iii] Vice-Presidents of the Russia Society included Winston Churchill and Lord Ullswater. In His book, The Origins of the Balfour Declaration, James A. Malcolm alleges that other prominent members included Chief British Rabbi, Joseph Herman Hertz and Zionist Propagandist, L. J. Greenberg of the Jewish Chronicle. He says both men felt that a greater understanding of Russia could help Britain better appreciate the plight of its Jews.

[iv] The influence brought to bear on the launch of U.R.S.A by Harry Cust can be found on page 4 of U.R.S.A Proceedings, Committee Members, vol.1, 1917 -1918, London, David Nutt. See separate entries, United Russia Societies Association and Robert Hobart Cust in this guide.

[v] Royal Manual of the Titled and Untitled Aristocracy of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, Edward Walford, Spottiswoode & Co, 49th Edition, 1909, p.156

[vi] Edward George Griffiths Burdon was related to Viscount Haldane on his Haldane’s mother’s side, Elizabeth Burdon-Sanderson (her father was Richard Burdon, born 1821). Another distant cousin, Rowland Burdon MP owned the mighty Castle Eden. It’s possible there was a relationship between the Burdon Sanderson Haldanes and the family of Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to Russia at the time of the 1917 Revolution.

[vii] Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury 04 September 1847, p.4, p.23, see also: 1881, 1891 Census, George & Frances Burdon.

[viii] The Letters of Horace Walpole, Fourth Earl of Orford. R. Bentley, 1891, p.19. The Walpoles were a family of clergymen, politicians, antiquarians and art historians, each descended from British Prime Minister Robert Walpole. Hugh Walpole, who Burdon joined at the United Russia Societies Association belonged to the same line. The Walpoles and Batheaston’s previous owners, the Millers inhabited the same social circles as Rowland Burdon, owner of Castle Eden and Conservative MP.

[ix] Another mock-Gothic mansion, Strawberry Hill House has also been credited as providing inspiration for the novel.

[x] The Tablet, Vol. 74, July-December, Tablet Publishing Company, October 19 1889, p.623. I believe the Brevet was a Higher Diploma awarded in France.

[xi] Mrs Tollemache at Bath, Votes for Women 14 March 1913, p.13

[xii] E.G.G. Burdon, 1914-1922, TNA, WO 339/72239

[xiii] War Office, WO 339/72239, Major E.G.G. Burdon

[xiv] Anglo Russian Friendship, The Times, February 21 1917, p.9

[xv] The State Duma was Imperial Russia’s version of the British Parliament or the US Congress.

[xvi] During the allied-war against the Bolsheviks, Rodzianko would come out in support of White Russian Generals Deniken and Wrangel. He had also been a leading voice in protests regarding the relationship between Empress Alexandra Feodorovna and Grigory Rasputin. By the time of the February Revolution a coup d’etat is alleged to have been already under discussion.

[xvii] Anglo Russian Friendship, The Tomes, March 28 1917, p.13. A similar advertisement placed in Russian journalist Zinovy N. Preev’s The Russian Revolution and Who’s Who in Russia in 1917 includes his full initials: ‘Major E.G.G. Burdon’.

[xviii] Tests for Proficiency in Russian, Derby Daily Telegraph February 9 1917, p.2. The address was also use for Maude’s Leicestershire Colliery and Pipe Company Ltd.

[xix] U.R.S.A Proceedings, Committee Members, vol.1, 1917 -1918, London, David Nutt, p.220

[xx] Anglo-Russian Friendship, The United Russia Societies Association, The Times, February 21 1917, p.9

[xxi] The Monthly Army List, Great Britain, Army, July 1918, War Office, H.M. Stationery Office, 355.0942 G786a. I

[xxii] The Navy List, United Kingdom, H.M. Stationery Office, 1917, p.548

[xxiii] Burdon’s Villa Belle Rive address can be found in Wills & Probate Records, Findmypast, Edward Griffiths George Burdon, 1937. The same address for Merlin can be found in Radio Amateur Callbook Magazine, Spring 1935, p.264

[xxv] Major E.G.G. Burdon’s £104,000 Estate, Kington Times 14 August 1937, p.4. Burdon’s Gothic New Court mansion is now a luxury hotel.

Suggested Reading

Anti-Semitism in British Society, 1876-1939, Colin Holmes, Routledge, 2016