The screening of Bleasdale’s 4-part Monocled Mutineer serial at the end of August 1986, might not have been the only thing to have brought down Alasdair Milne as Director General of the BBC, but it sure as hell contributed to just how fast he was shown the door.

The legend that has grown up around the show over the years is that Milne had been sacked over his decision to reveal the secrets of a mutiny that had managed to stay classified for the best part of 70 years. It isn’t entirely true, of course, but nothing is entirely anything when you begin to examine the details. It’s very often the case that during prolonged heated exchanges, fact and fiction become fused.

The 1980s was the ‘bang’ era, a period defined by a twin insurgency of short-fused quasi-socialists and boisterous entrepreneurs: history itself was in some kind of meltdown.

When the Hurly Burly’s Done

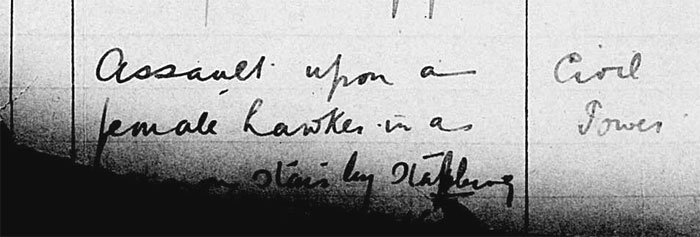

As regards the purported riots on which the series was based, there’s little doubt there had been something of a cover-up. When Sylvia Pankhurst’s Worker’s Dreadnought first published news of the mutiny in November 1917, its office was duly raided by Police (Birmingham Daily Gazette, 12 November 1917, p.3). A letter had arrived on their desks from a soldier who had witnessed ‘a big racket’ featuring 10,000 men that had broken out across Etaples during the first two weeks of September. Even the paper was quick to acknowledge its surprise that the letter had made it past the Base Censors. Feminist author and Etaples nurse, Vera Brittain supported the claim. In her 1933 autobiography, Testament of Youth, Brittain describes not being allowed to mention the episode in letters home and how it appeared “not unnaturally, to have been omitted from the standard histories by their patriotic authors”. The ‘Battle of Etapps’, as she calls it, had carried on into mid-October, and was said to have been followed by the resignation of “numerous highly placed officials” and the suicide of a young officer in the camp’s notorious Bull Ring (Testament of Youth, Vera Brittain, Victor Gollancz, 1933, p.386).

The next sneaky peek at the disturbances at Etaples leaked from the pen of C.E Montague writing in the Manchester Guardian. ‘Hotspur and the Brass Hat’ offered a slew of caustic quips. “One almost expects to find something in Henry the V about the Mutiny in Etaples”, writes Montague 1. It was just four words in total. The Mutiny in Etaples. Not ‘a mutiny’, not ‘some mutiny’ but THE Mutiny. It hinted at a secret shared.

A full ten years elapsed before the first full account appeared in the British press. In February 1930, The Manchester Guardian ran the headline, The Mutiny At Etaples: An Incident of 1917, Fighting Soldiers and Red Caps. The 2,000 word exclusive had been submitted by an S. J. C. R. For a few weeks there was an excitable flurry of letters from witnesses, but within months it had been forgotten. Boisterous Socialists like J.J Davidson, Labour MP for Glasgow, would make veiled yet provocative allusions to it in parliament, but by and large, the combined forces of civility, respect and embarrassment kept most lips firmly shut. The tale may have teased the lips occasionally. The tongue may occasionally have shot forth. But it never really did any serious damage. Not even a glimpse of Lady Forbes’ knickers could have broken the silence any.

But all that changed in the nineteen-eighties when BBC producer, John Purdie invited gritty English screenwriter Alan Bleasdale and Scottish director Jim O’Brien to take the nuts and bolts of John Fairley and William Allison’s 1978 book, The Monocled Mutineer and transform it into a scorching 4-part drama serial.

The culmination of this period was that occurrence, chiefly disgraceful to writers about the war who appear to be in a conspiracy to conceal it, the Mutiny at Etaples. All countries engaged in the war had periods of widespread mutiny, a fact which should be noticed and recorded, not hushed up. . . . With the British it occurred . . . over some rumoured disagreement with the police. I never knew the truth and perhaps no one knows it.

The 1930 Manchester Guardian report on the Etaples Mutiny featured the above passage from R.H Mottram’s Three Personal Records of the War.

The response to the first two episodes of Bleasdale’s explosive drama had been broadly favourable. Even The Daily Mail had been impressed. Paul McGann’s performance was ‘brilliant’, the show’s depiction of the war-time horrors, ‘graphic’ but the general consensus was that the scenes of the boys in the trenches reflected the true spirit of British fighting men at the front. It brought the world of Wilfred Owen to life some thirty-years before Peter Jackson’s digital trickery would pump reservoirs of re-oxygenated blood into those jerky, lifeless limbs we saw in those crude old movie-reels.

It wasn’t the first time the BBC had a chance to screen a drama about the mutiny. Former actor Leslie Glazer had his play about the events rejected in the early 1970s. The BBC ’s explanation was quite ironic; the board was a little “unhappy about the mix between fact and fiction” (New Dispute Erupts Over Monocled Mutineer, The Times, September 26, 1986, p.2)

The problems for Milne and the Beeb really arrived with the mutiny scenes. During a period in which Britain was facing a barrage of nationwide strikes and riots, the scenes of rampaging soldiers flooding the town of Etaples in an all-raping, all-pillaging fashion was too much for Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government to bear. The drama had touched a nerve with an already nervous Tory government. The fact that the handsome and witty young Paul McGann was making revolution look rakishly attractive can’t have eased those fears much either.

By the time that the third installment of the drama was due to go out on Sunday 14th September, the BBC was near to collapse. The sudden death of top BBC Governor, Stuart Young, three days before the drama’s first episode was due to be screened, allowed the Conservative Government to install dedicated Tory oddball, Marmaduke Hussey in his place. Thatcher said that Young, originally installed at the BBC as safe pair of hands, “had gone native”. His days had been numbered anyway, by all accounts.

Bleasdale’s ‘Marxist propaganda’ couldn’t have arrived at a better time for the Tories. And it wasn’t much of a secret either. According to Conservative Party Chairman, Norman Tebbit, Hussey had been specifically appointed “to get in there and sort the place out … and in days not months”. And if anyone would know it was Tebbit, who was already in the process of compiling his own 21-page dossier on left-wing bias at the BBC over its handling of US bombing raid on Libya that April, and a Panorama episode about right-wing extremism within the Tory party (Panorama Accused of Left Bias, The Guardian, Nov 19, 1986, p.2).

The man they had in their cross-hairs was BBC Director General Alasdair Milne whose repeated acts of insubordination over the years at the BBC (dubbed the Bolshevik Broadcasting Corporation by Britain’s right-wing press) had elicited the wrath of Thatcher and her right-hand man, Willie Whitelaw (Right man, right time, for all the right reasons, The Guardian, 23 Sep 2001).

The news of Hussey’s formal appointment on October 1st was greeted with amazement and trepidation at the BBC. The former director of Times Newspapers had absolutely no experience in broadcasting, and reportedly, even less interest. Milne himself only learned of his appointment at a European Film and News Conference. He said he was both ‘surprised’ and ‘intrigued’ by the arrival of Hussey. And there was no one less bewildered than Hussey. On receiving word of his appointment from the Home Secretary, Douglas Hurd, his awkwardly mustered response was, “This is most astonishing” (An Astonished Duke Chosen to Head BBC, The Guardian, 02 Oct 1986, p.1).

Milne’s decision to screen The Monocled Mutineer was the latest in a long list of transgressions. A controversial interview with Martin McGuiness for Real Lives and the short-lived go-ahead on Duncan Campbell’s Conspiracy-led ‘Secret Society’ (about about secret Cabinet committees and Mi5) had done much to sour relations between the corporation and Conservative Top Brass.

Whitelaw’s friendship with BBC Chairman Ian Trethowan (believed by many to have played a key role in the shelving of the Campbell documentary) had gone some way towards restoring some kind of balance at the station, but the insufficient patriotism displayed by the BBC during its coverage of the Falklands conflict, meant Trethowan was on his way 2.

The fact that The Daily Mail led the front-line attack was clearly no accident either. Hussey had launched his career at the Mail and was a personal friend of its owner Lord Rothermere.

Thatcher and the Conservatives were faced with another problem too; former Home Secretary and Deputy Leader of the Conservative Party, Willie Whitelaw 4 was an old associate of Norman de Courcy Parry, the man generally regarded by locals as having fired the shot that killed Percy Toplis. That Norman was a civilian at the time, and present only at the ambush on the expressed wishes of his father, the Chief Constable of Penrith, Charles de Courcy Parry, introduced another toxic variable into the mix. Whitelaw had served as MP for Penrith for the best part of thirty years and knew Parry intimately through hunting circles. The Penrith Observer of 1954 shows Parry and Whitelaw together at an event to mark the John Peel centenary celebrations in Caldbeck some 12 months prior to being elected. The BBC was also there (Penrith Observer, October 19 1954, p.12) 3. Just as curiously, the man brought in to force the resignation of Alasdair Milne at the BBC, Marmaduke Hussey, was another of Parry’s wider hunting circle. As was Hussey’s predecessor, George Howard. Hussey’s wife was Lady Susan Hussey, Lady in waiting to the Queen since 1960. This was really as posh, and as Conservative as it got.

In 1986, full-on class-war had never seemed so imminent. Whether or not the threat had any plausible basis in reality really didn’t matter. It was images that mattered. Just as it was images that mattered when building the war on terror. If you grew up in the eighties you’ll know that whilst it was the Rah Rah Skirt and Mr Rubik that captured the imagination of shows like I Love the 1980s, it was the riot-shield that really stuck with those who were living through it. The riot-shield was a constant visual reminder of just how frighteningly thin British defences were against all-out bedlam. Barely before the fifth dong had rung out on News At Ten, you’d have had the latest on the riots at Hansdworth or the Broadwater Farm estate, or a montage of battlefield tactics being ruthlessly enforced by Police on some slow-witted flying-picket at a plant or pit in Rotherham. And despite its best efforts, not even the foam at Spitting Image was enough to absorb the blows.

All the Kings’s horses and all the King’s men couldn’t put Britain together again. Things hadn’t been as volatile as this, since Percy was around the last time. The last thing that anybody really needed at this point was a poster-boy for revolution. Certainly not one that had crawled-up from the pit.

Whitelaw may have sensed trouble brewing. Had his old friend Parry’s less than discreet confessions and boasts handed the bristling working classes some much desired fuselage against their betters? Was it only a matter of time before press and public scrutiny turned to the less than transparent circumstances surrounding the death of the nation’s posthumous hero? As it was, the Defence Secretary, George Younger was already coming under increasing pressure to release all official records of the mutiny including the fabled reports compiled by the hastily convened Haig Board of Enquiry on September 10th 1917 (Etaples Base Camp Diaries, WO 95-4027 5, National Archives).

A Dead Man On Leave

Almost overnight, a tapestry of uncomfortable facts had become a tissue of fiction. “There was no rape, only one death and Toplis wasn’t even at the Mutiny”, snarled the headlines of The Daily Mail. The show’s historical adviser, Julian Putkowski 5, had been drafted in by the Mail to provide the fatal bullets. He claimed the finished drama bore no relation to the facts that he had uncovered during the course of filming. It was Putkowski‘s belief that the script was “riddled with errors of fact and interpretation” (Tissue of Lies on the BBC, Daily Mail, September 13th 1986). The BBC’s Managing Director, Bill Cotton defended the series as a “play about the greater truth of the First World War” (MoD Asked to Release War Mutiny Records, The Guardian, 16 Sep 1986, p.2). The rape scene whilst broadly regarded as ‘gratuitous’ at least emphasised the explosive mix of sexual frustration and the mens’ rabid efforts to restore some self-determination. Brutality breeds brutality was clearly Bleasdale’s message 6.

It was interesting timing certainly. Just a few days previously, David Crump, staff photographer for The Daily Mail had been sent up north to prepare a feature on Percy’s illegitimate son with Dorothy (played in the show by Cherie Lunghi). Percy Cupit had been born in January 1921, the year following the Toplis ambush. Although the young family had lived in Shirland with Percy’s mother for a short period of time, Percy Jnr knew little about his father. In Crump’s photo, Cupit can be seen affectionately holding up a picture of a stout young soldier. It might be Toplis, it might not be. The man in Cupit’s picture, mysteriously enough, is wearing the distinctive Tam O’ Shanter of a regular Scottish soldier as well as a cosy, sheepskin jerkin. Both details raise more questions than they answer.

But there are clues here about something else. The photo of Percy Cupit fondly holding the photograph of the soldier may give us some indication where the story was heading prior to Thatcher and Whitelaw’s plans to appoint Hussey at the BBC. Cupit is smiling rather proudly in the photo. This might suggest that the paper’s editor, David English, was still intending to promote Toplis as ‘good guy’ or ‘peoples hero’ — some chap you could be proud of.

To the best of my knowledge the report that The Daily Mail was preparing about Percy Cupit was never published. Instead, they went with a report on the ‘historical inaccuracies’ of the drama. What changed the Mail’s direction so suddenly? Perhaps we’ll never know, but a change in editorial direction is likely to have been synchronous with a renewed confidence among Conservatives that normal service — and control — would soon be restored with Hussey.

Within weeks of the series finale being aired on the BBC (September 1986) the BBC’s 55-year old Director General, Alasdair Milne was press-ganged out of the job by Thatcher’s hatchet-man, Marmaduke Hussey. Interestingly enough Alasdair Milne had served in the same Scottish regiment that had been at the centre of the Etaples Mutiny: the Gordon Highlanders. It had also been Milne that had brought us the explosive, wall-to-wall coverage of the UK miners’ strike. Pioneering work on the 26-part 1960s documentary, The Great War, was also to his credit.

To date, the BBC has never repeated the series on any of its channels despite the renewed interest and opportunities presented by the centenary celebrations marking the end of the Great War and the Russian Revolution.

In April 2017, Under-Secretary of State for Defence Mark Lancaster killed any remaining hopes of the Haig Board of Enquiry records relating to the Etaples Mutiny ever being released. Chris Evans Labour and Co-operative MP for Islwyn was told that no records pertaining had been retained by the MOD.

поддельные новости: The Monocled Mutineer and the Red Under the Bed documentaryTweets by repeat_the_past

Links

Part II – поддельные новости: John Fairley and the Red Under the Bed documentary

The conception and publication of Fairley and Allison’s Book, The Monocled Mutineer plus Fairley’s role in the controversial Red Under the Bed documentary

Inadmissible Memories of a Suppressed Mutiny, Bill Allison, Guardian, September 22nd 1986

Further Reading

Heartbeat and Beyond: 50 Years of Yorkshire Television, John Fairley, Graham Ironside, 2017

Splashed!: A Life from Print to Panorama, Tom Mangold