The role played by scholar, academic and adventurer Bernard Pares in Britain’s relationship with Imperial Russia and the signing of the Anglo-Russian Convention continues to be overlooked in popular history. This article explores the complex relationship between Pares’ groundwork for the Russo-British Chamber of Commerce in 1907, the British Russia Bureau during the First World War and his subsequent work for the United Russia Societies Association, the Committee on Russian Affairs … and the very first English translation of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

A highly motivated swashbuckling academic and old school adventurer, Sir Bernard Pares (March 1867 – April 1949) earned himself the distinction of being the most respected authority on Russia and the Slavic States from the early 1900s until the 1940s and the weight this “wandering student” of Baltic history carried in the anti-Bolshevik campaigns of the 1918 to 1922 period may be crucial to understanding both the context for the production of the first English translation of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and the sheer weight of scholarly opinion favouring a Liberal rather than Bolshevik Russia during this critical period of Anglo-Russia relations. Pares may also represent the point at which the scholarly enthusiasm of Russophiles like Harold Williams and himself collided with the forces of commercial enterprise, and the economic realities of international relations that formed the bedrock of bi-lateral treaties with politically divisive and often unpopular regimes. When governments were not able to draw on the in-roads made by their various diplomats and ambassadors, self-funded individuals like Pares and Williams would provide the only available access to foreign governments and world leaders, their contacts and expertise very often producing more effective policies and their timing and serendipity providing greater opportunities to act. However, to what extent Pares was acting of his own volition, and just how immune he was the influence from trade magnates like Sir Alfred Jones and Thomas Henry Barker, in agreement with the British Foreign Office, during the first phase of his career, is rather more difficult to ascertain.

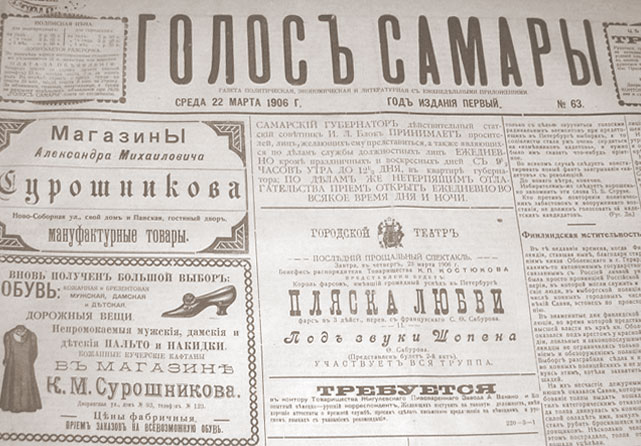

Just like his father and grandfather before him, the small but spirited Pares had been educated first at Harrow and then at Trinity College, Cambridge [1]. During his travels abroad in the mid to late 1800s, this restless young man would plunge himself into the work, arts and culture of his host country, before making any attempt to unravel and predict its deeply unfathomable politics. His experience of Russia, much like his experience of Italy, France and Germany, was rooted in an obsessive immersion in its mysteries, which he would then strip down to the bone after tearing away at the flesh of its many falsehoods to reveal the raw elements of its character and its soul. As far as Pares was concerned, Britain’s understanding of Russia had been totally mismanaged by Germany, believing that from Bismarck onward, it was the “settled policy of Germany to keep England and Russia in permanent misunderstanding”. [2] After extended fact-finding stays in Paris, Metz, Stuttgart , Berlin and Florence, Pares finally arrived in Russia in 1898, desperate to learn the language but without any formal reason for being there. After becoming acquainted with a young and liberal newspaper correspondent called ‘Basil’, a recent graduate, Pares would eventually find work at the Volga newspaper, Golos Samary (The Voice of Samara), with ‘Basil’ as its editor. [3] Writing in Mobilizing the Russian Nation in 2016, historian Melissa K. Stockdale describes the newspaper as one of many covertly funded and privately owned periodical used by the Imperial Government to influence public opinion. The scale of these secret subsidies, which were only revealed after the February Revolution, showed the extent to which the regional monarchic press had gone to maintain conservative and loyalist narratives. In 1912 alone it was estimated that over 600, 000 roubles had been secreted to the right-wing press, with at least one of them, Mir Islama, directed at Muslims.[4] After an introduction from Bishop Mandell Creighton of London to Professor Paul Vinogradoff of Moscow University, Pares was given the privilege of hearing lectures on a free and fairly casual basis.

https://kraeham.livejournal.com/45221.html

After returning to England, the thirty-year old Pares found himself enrolled into the University Extension Movement, a scheme developed in England to provide tertiary teaching for those unable to attend University, an early attempt to grease the wheels of social mobility and improve essential knowledge on complex issues that were likely to have some bearing on the policies of the day among the rising middle and working-class masses. Between 1898 and 1904 Pares would lump his suitcase and his papers across the length and breadth of England holding talks on everything from ‘The Rise of Napoleon’ to ‘Austro-Hungarian Dualism’.[5] His switch across to the Extension Movement under Liverpool University in 1902 allowed him to “go deep” in a more concentrated area, an approach that would help foster the growth of supplementary reading groups. It was here that Pares encountered shipping magnate, Sir Alfred Jones, the President of the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce who had only that year launched a Russian Trade Section of the Chamber under Jones’ long-term partner, Thomas Henry Barker after a visit from another Cambridge graduate, Henry Arthur Cooke, the British Commercial agent in Moscow. Cooke had arrived from Russia in February that year and was determined to make good on the promises made by Lord Salisbury and Balfour in a scheme that had been conceived in the final years of the 19th Century to adjust the relations between Russia and Britain, specifically in relation to China.[6] According to a report of the meeting published by the Liverpool Journal of Commerce, Cooke had arrived in Britain to address the prospects of developing trade. There was, Cooke believed, a great desire in Russia to open up more markets for their agricultural products. Germany was about to raise the duties on such merchandise, and should the anticipated Tariff Bill be allowed to pass, its trade with its neighbour would be considerably downgraded. As a result, Russia now wanted to increase its exports to Britain, and stimulate greater engagement from British traders at the various exhibitions it held annually in St Petersburg. Cooke hoped it would be possible to create something along the lines of an Anglo-Russian Chamber of Commerce, but a lack of understanding of Russia’s culture, and an almost insurmountable language barrier was constantly retarding interest among traders and their agents.[7] Cooke had encountered another problem. As far as the Moscow region was concerned, the larger proportion of companies were still conducted their trading operations via the British colony in Moscow [8] — the remnants of the old Russia Company whose leading agent was James Shanks, grandfather of Protocols translator George who was at this time conducting much of his finances through his nephew, Léon Lvovitch Catoire, board member of the Moscow State Bank and later adviser to the Moscow State Duma. As Cooke explains in correspondence to the British Foreign Office, the naturalised English colony resented any government interference in their business. All attempts at developing trade were likely to need their cooperation. By 1919, The Russia Company’s last President, Evelyn Hubbard was sitting alongside fellow Company members, James Aaron Bezant, John P. Blessig and Professor Bernard Pares on the executive board of U.R.S.A.[9]

On the 28th October, 1902, steps were taken the Liverpool Chamber’s Secretary, Thomas H. Barker, to form a Russian Trade Section of the Chamber and the very first meeting was held in November. By December, Hermann Decker had been elected Chairman and Mr H. Clements, Vice-Chairman. Decker conceded that whilst the Russian Government was difficult to access, if reasonable proposals could be put through the Russian Trade Section they were guaranteed to receive the most careful attention. In August the following year, Thomas H. Barker met with Russian diplomat, Paul Lessar, who gave him a letter of recommendation to the Russian Authorities in Siberia. By February 1903 it was being reported that a new Russian General Customs tariff had been approved and sanctioned by the Tsar now favouring trade with Britain and discouraging trade with Germany.[10] Whilst Pares omits any suggestion that his move across to the University Extension program at Liverpool from Cambridge in 1902 was not in any way related to the formation of the Russian Trade Section under Barker and Sir Alfred Jones, its curious timing to say the least. In his 1948 memoirs, A Wandering Student Pares suggests that only once did Sir Alfred ever put to him a question which could have had interest to him in his own business. He is said to have enquired if there was a shipping line in St Petersburg that would take emigrants directly to America.[11] In the context of what we have learned above, it seems doubtful that Jones or Barker had no personal interest at all in feathering their own nests or those of their members. It also seems doubtful that Pares had no interest in politics. A letter published in the Manchester Guardian in September 1904 shows Pares expressing his own frustrated response to British opinion of Russia on the Russo-Japanese War and Russia’s rejection and misreading of British neutrality. Writing from Smolensk Pares explained, “Russia as a country did not want war with Japan. The Emperor too, did not want it. The Russians therefore look at the war as an inconvenience. They believe that Japan would not have dared to attack except for the moral support of England. Of what nature was this support?” [12]A similar protest published in The Times of London the month before thanked the “effective assistance” and “hospitality” that he had received from both the Russian Government and “private individuals”. Contrary to what many people may have been reading in England, the support of the Revolutionary movements in the towns was “quite unlikely”, and in the country “quite out of the question”. Most troubles were described in social rather than political terms, and there was almost a universal feeling that the war came first. [13] The considerable progress he’d been making was at risk of being blocked by the knee-jerk reactions of one Colonial power to the protective reactions of its rival, with the whole misguided drama, to Pares mind at least, being none too subtly staged-managed by the envious Germans. Any advances the two countries had made in its commercial program would have to endure a further two years of retardation.

Sir Alfred Jones & the School of Russian Studies

One thing we can be certain of, is that by the time that Pares had initiated plans to launch the School of Russian Studies at Liverpool University in 1907, he was delivering highly charged lectures organized by the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce on British trade solutions with Russia. In an event chaired by Sir Alfred Jones and Thomas H. Barker in the first week of November that year, it was explained how there was considerable scope for development between Russia and Britain, but that it would dependent on a “keener and wider knowledge” of the Russian language among British traders. Just several weeks earlier, the British Liberal Prime Minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman had signed the Anglo-Russian Entente pact, which would dramatically redraft their respective colonial influences in the Persia Gulf, and ultimately setting the agenda for the war ahead.

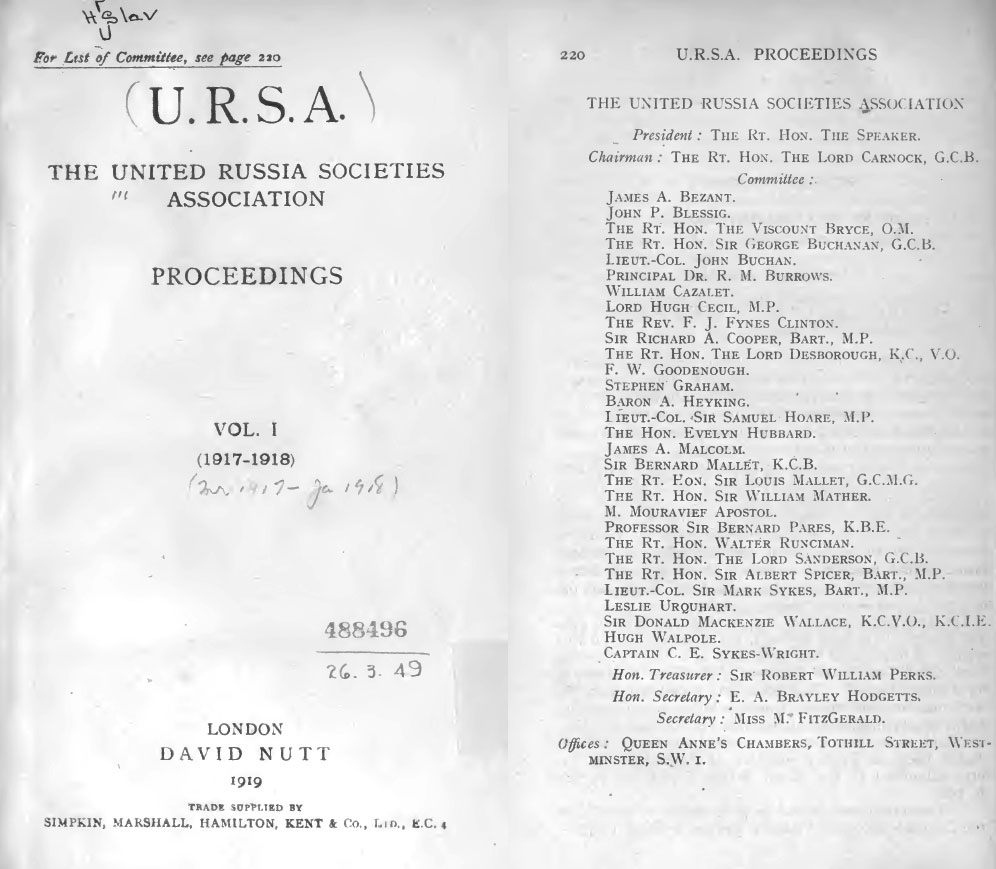

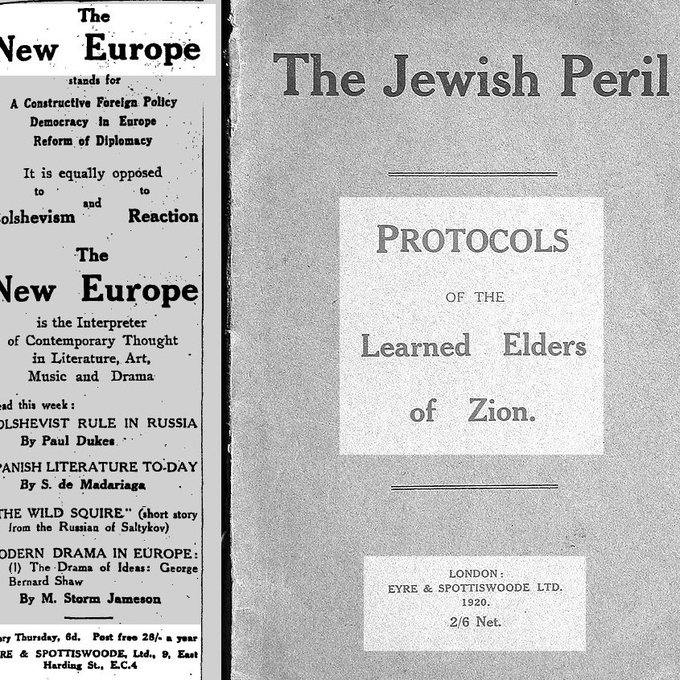

Pares followed this up this introduction by assuring his audience that Russia was “big enough in every aspect of trade and in natural resources” to justify the special efforts needed. The country’s ignorance of Russia had put them “at the mercy of Germany”, having based much of their understanding of the nation on German knowledge and German politics. Our antipathy had been influenced by German antipathy. Practically all the Englishmen who had lived in Russia liked the Russians. The Russians also liked them in turn. Pares reserved the greater part of the blame, however, on Britain’s failure to grasp the language and an almost “absolute disregard of the conditions of the country”. [14] What they needed was a school dedicated to Russian Studies and by 1908 they had just that. Joining him as faculty members at the school would be Shanks’ uncle Aylmer Maude and Pare’s old friend, Harold Williams. The project would be followed by the School of Slavonic and East European Studies with Robert Seton-Watson in 1915. In 1916 the two men founded the New Europe journal. The journal was published by Protocols printing company, Eyre and Spottiswoode, as was their subsequent publication, The Slavonic Review, which would eventually include contributions from Protocols expert witness, Vladimir Burtsev. [15]

The efforts that Pares’ sponsors had put in to stimulating trade between Russia and the United Kingdom was duly acknowledged at the end of June 1909 when delegates of the Russian Duma visited the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce. The extremely unpopular constitutional challenges that Russia had met and overcome by granting legislative and executive to its people now meant that the sympathy of Britain and America could be extended to the lands of the Tsar. The reservations that British Capitalists had had were now removed and hopes were being focuses on its generous mineral reserves. [16] After landing arriving on June 21st in London, the delegates were provided with opportunities to talk informally with the Secretary of State for War, Richard Haldane and the then serving President of the Board of Trade, Winston Churchill.[17]

The visit to Liverpool on June 28th in the Senato Room of the University would include the Duma’s finance Secretary, Herman Lerche, liberal historian Pavel Milyukov in addition to M. V. Chelnokov and Aleksandr Guchkov. [18] As a measure of faith in the relationship and the demonstrated the firmness of their resolution to strengthen their relations, plans were drawn up to form a Anglo-Russian Committee with Pares elected as its Secretary at its London branch. Senior members of the Committee in Russia included Nikolay Khomyakov, Guchkov and Boris Suvorin, editor of his father’s deeply Conservative newspaper, the Novoye Vremya and brother of Alexis Suvorin whose more Liberal Rus newspaper had at one time employed the future Zionist and British ‘Mule Corps’ leader, Ze’ev Jabotinsky.

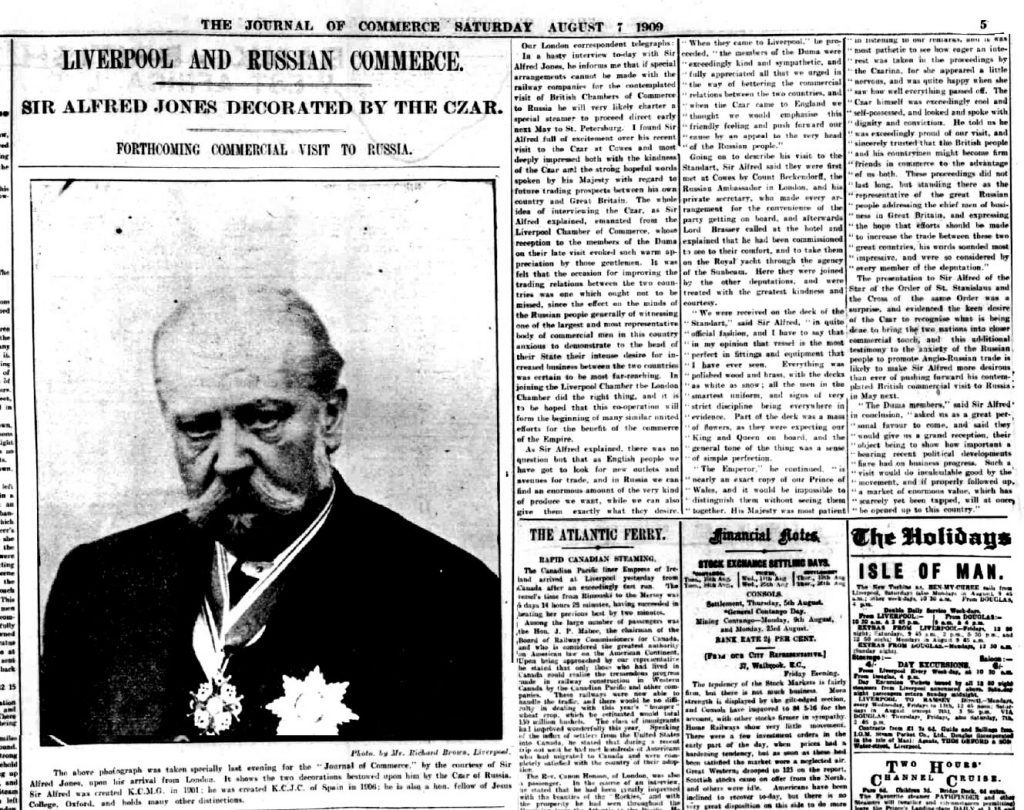

The engagement in Liverpool was immediately followed up by an address in London in which Sir Alfred and the men of the Chamber enjoyed a personal meet with the Tsar to discuss the launch of a Russo-British Chamber of Commerce in St Petersburg. [19] As a measure of his appreciation, the Tsar presented Sir Alfred with the highest honour that the House of Romanov could give: the Star of the Order of Saint Stanislaus. Full of excitement after his meet with the Russian Ambassador, Count Beckendorff and the Tsar on board the Royal yacht, the Standart, during his visit to Cowes on the Isle of Wight, Sir Alfred explained that if special arrangements could not be made by railway companies, then the British Chamber of Commerce would charter a special steamer to St Petersburg next May. The English people had to look for new outlets and avenues of trade, and Russia provided the kind of produce they needed. He also made a point of mentioning the astonishing likeness between His Majesty and the Prince of Wales. It was practically impossible he went on, to distinguish them “without seeing them together”. [20] As Jones was in the habit of concluding, the “best peacemaker and peacekeeper was trade” bringing as it did “a mutual interest” that provided “an almost unbreakable tie”. [21] Sadly, the celebrations weren’t to last. In December that same year, just weeks after announcing his scheduled trip to Russia, Sir Alfred died of heart failure at his home in Liverpool. According to Liverpool’s local press, the 63 -year old shipbuilder and imperialist had begun to cancel his engagements after contracting a cold shortly a meeting with Colonial Administrator, Sir Hesketh Bell in London that November. A favourite with the Colonial office and a close personal friend of the former Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, the pair had been reviewing the success of a series of meetings that Jones had chaired with the German Colonial Secretary, Bernhardt Dernburg in the first few days of the month, in which they discussed cooperation between the two countries in their efforts to develop civilisation and commerce in West Africa, in the hope that it might, among other things, alleviate the long-time British dependence on American cotton. In attendance that day was the Imperial Russian Consul, Antoine Wolff (a descendant of a Baron Wolff of Germany) and Julius Pisko, the Consul General for Austria-Hungary. [22] How the governments of Russia or Germany reacted to the news that Jones was romancing both countries at the same time is open to speculation, but in the context of the intense rivalries between Russia and Germany during this critical pre-war period, one might assume it would have been lukewarm to say the least. The man who a rather perplexed David Lloyd-George was to describe posthumously as “not a man but a syndicate” was certainly walking a thin. In a macabre twist, the picture used to lead the tributes in Britain’s national and regional press was the one that had been taken in August on his receipt of his Tsarist ‘Star’. [23] Without the funds and resources that Jones was able to bring to the initiative saw the plans the group had made for a reciprocal visit to Russia in spring collapsed, a failure that historian Michael Hughes would more tactfully attribute to “a welter of administrative minutiae”.[24]

On the day that his death was announced, Bernard Pares received a telegram from both the President of the Russian Duma, Nikolay A. Khomyakov and Bernhardt Dernburg, the German Colonial Minister that Jones had entertained in Liverpool just one month previously. Both men conveyed their deepest sorrow to Pares and Sir Alfred’s family, with Khomyakov extending his thanks for Jones’ personal contribution to Anglo-Russian rapprochement. [25]

Sir Alfred’s death came just days after it was announced that the very first Russian editions of the ‘Commercial Intelligence’ bulletin from the Board of Trade and Commerce were due to be published in Britain. Plans were also being made to print all future publications in Russia. Intended to serve as an organ of the British export trade with Russia, it was believed that the bulletin would launch with a guaranteed circulation of 7, 000 copies. [26]

There was probably no one more devastated by Jones’ death than Pares himself who had made one of most passionate appeals for further funds just a week prior to the arrival of the German Colonial delegation. At noon on November 1st 1909 with Sir Alfred presiding, Professor Pares rose before a panel of Liverpool’s most influential men of commerce and engineering in the boardroom of the city’s Cotton Exchange Buildings, and put forward his strongest case to date for the development of trade with Russia. Both men were of the opinion that the visit of the Russian Duma to Liverpool and Sir Alfred’s private conversations with the Tsar at Cowes was one of the most satisfying things the Chamber had experienced. A formal invitation had now been extended to the Chamber to visit Russia the following spring and it was their strongest intention to go. Sir William Mather, Christopher Furness and W.H. Lever MP were also expressing their desire to go. Negotiations were now taking place and Pares was very much at the centre of them. At present “considerable development was taking place in agriculture”, especially in terms of cooperative farming in the Baltic. One third of grain imports were also now from Russia. This was, moreover, “abundant proof” that Russia, for good or bad, had entered into the “capitalist period” of its history. The masses were looking at having more, and wanting more in terms of property. Trumping German in trade with Russia depended on one thing and one thing only: the language skills and knowledge bases necessary to compete. Whilst Pares was cautious enough to see that Russia was likely to preserve its protectionist position for some years to come, the financial reconstruction taking place in that country under the current Liberal Duma offered some room for hope. This was “not a Duma of Revolutionaries but consisted largely of men that had passed through high administrative positions”. What was needed now was “serious and solid journal that would give information to public bodies”, a steady stream of credible commercial intelligence; a levelling up of knowledge with that of Germany. At this moment Pares tabled the establishment of a further school of research at the University, as no other University in England had taken such an interest in Russia as this one. Sir Alfred set the ball rolling by pledging £100 a year for three years to Pares’ project. [27]

In the days that followed a generous three column piece in The Times fleshed out some statistical details. The paper’s special correspondent in St Petersburg, Maurice Baring was like Pares, a graduate of Trinity College Cambridge and shared his obsession with Russia. The report started by pointing out that in just sixteen years Russian imports had practically doubled in size but during that same period had remained “practically stationary”. Meanwhile German exports to Russia had more than trebled, increasing from £10, 624, 000 in 1893 to £33, 779,521 in 1908, the proportion of manufactured goods rising by 46%. Russia’s desire to improve trade relations with Britain was coming from a political rather than economic imperative, realising that its reliance on Germany made it vulnerable to pressure. Berlin had poured time and expense developing its consular relationship with Russia and Britain had done practically nothing. It also did nothing to promote its manufacturers. The formation of the Russo-British and London Chamber of Commerce looked set to change all that. Representatives from both countries were in the process of organizing an exhibition in London in 1911 for the display of Russian products, and a further exhibition in St Petersburg for the promotion of British products. The paper was at pains to point out that these “noteworthy opportunities”. [28]

In his memoirs, Pares describes how he had been in communication with Sir Alfred in the days leading up to his death, receiving the last of his letters, which he would write at least twice a day, on the very day that he died. [29] Jones had been keen for Pares to address the London Chamber of Commerce and then go to the Foreign Office “to say so and so”. His secretary had mailed Pares another letter that had to make the post, written within hours of their last scheduled meet. It read, “Why didn’t you give that little fellow Pares a better chance of seeing me? He was looking dreadfully ill; we must give him a voyage to Madeira.” [30]

On Intelligence Matters

At the onset of World War I, his involvement at the Russian School in Liverpool was put on hold as Pares was dutifully enlisted as Official Correspondent of the British Government on the Russian Front after being introduced to the Intelligence Department of the Russian Third Army as an “Expert of the Foreign Office in East European Matters.” [31] Much of his work, syndicated to the press of Britain, in a typically ‘Boys Own’ adventure fashion, appears to have been calculated as a means managing and perhaps even sanitising the information flow from the various campaigns being carried out by the Russians in Poland. In an interview with The Daily Chronicle upon his return to London in August 1915, Pares summed up his impressions of the Eastern offensive:

“The War in Poland has revealed Russia at her best. When I left the Third Army in Galicia at the end of June the Germans were fifty miles from the south of Lublin. They took a month to get there and that’s not bad work for the Russians …

… I say deliberately and emphatically than on the whole of the Russian front, and I could go where I liked and talked to whom I liked, I have not seen or heard anything brutal or beastly done by the Russian troops. They have fought most humanely in this war, almost too humanely, sometimes think.” [32]

The interview had come in response to news that during the withdrawal of Russian forces from Galicia and Poland the units had embarked on a ‘scorched earth policy’ of looting and destroying anything of practical use to the advancing enemy. This would involve seizing assets and evicting, deporting and neutralizing all locals suspected of collaboration with Germany. [33] The number of those suspected would include over 500, 000 Jews. Inevitably, reports of Pogroms began to emerge, committed for the most part by Russians but also by Polish Separatists. Tales of Russian atrocities against the Jews had been swelling since January when the Jewish Press of America very cautiously printed stories by eyewitnesses like Arthur Levy from Lodz who gave an account of the abuses being carried out by the Cossacks in the village of Chozew near Widawa. [34] Another story, providing much greater detail, emerged in August, when the New York Sun, The Day and the Jewish Sentinel ran ‘The Kuzshi Story’. The story, printed in Nash Viestnik, the official news bulletin of the Imperial Russian Army, had circulated an entirely fictitious account of a major betrayal by Jewish villagers who, the Russians had claimed, had hidden bands of German soldiers in the cellars of their houses. As news spread, a paralysing terror is said to have spread among Jews of the Poland who now feared instant reprisals from Polish peasants completely ignorant of the truth. In actual fact there were only three Jewish homes in Kuzshi and none of them had cellars. According to the author of the report, “the millions of ignorant peasants in the villages, the Black Hundreds in the cities —in fact almost the entire land — believe to this day that the Kuzshi story is true.” [35] Lublin was finally captured by the Austrians on August 1st. Warsaw soon followed.

Shortly after Pares arrived back in Britain, a stream of appeals requesting donations to the Russian Jews Relief Fund organised that summer by Sir Leon Levison began to appear in the British Press. In a move that had been clearly designed to spare the embarrassment of the British Government, the appeals, where they were explained at all, were phrased rather tactfully: “The German advance in Poland had driven vast numbers of Jews out of the country. They are homeless and starving”.[36] It wasn’t a lie exactly, but neither was it the truth exactly. The US millionaire Jacob H. Schiff wasn’t quite so tactful. Writing in the American Jewish World in September 1915, Schiff first acknowledged his German sympathies before explaining how it was only the ruthless withdrawal of the Russian Army that summer that had heaped such suffering on the Jews. If anything, Schiff continued, it was the arrival of the Germans who had offered them the safety they needed. Schiff also voiced his fears that England had been contaminated with by alliance with Russia: “England doesn’t want to do anything that is displeasing to her ally, more through fear to offend than for her respect for her.” [37]

After his post as ‘eyewitness’ (or rather, censor) with the Russian armies had been abolished without explanation on his return, and his ‘Day by Day accounts with the Russian Army’ disappeared from the columns of the press, Pares had found himself drafted into organising British Propaganda and Intelligence efforts in Russia as part of the British Russia Bureau at the personal request of George Buchanan, the British Ambassador and the Director of Military Intelligence, General Macdonogh. [38] Interestingly, Pares hints at ‘a partial explanation’ in his memoirs of the 1930s and 1940s. “It was just about this very time that the Empress was starting her great and successful fight against the Duma, and it was at the Dumas requests that I had been brought to England.” [39] It wasn’t his failure as a war correspondent that had brought him home, but concerns among the ranks of the Empress’s “illicit relations with Rasputin” and her perceived “pro-German views”. [40]

The British-Russia Bureau

In either 1931 or 1948 memoirs, his account of his dismissal from his post as ‘observer’ includes no reference at all to the brutal withdrawal of the Russian forces from Poland. Instead, Pares recounts a conversation he alleges to have had with British Munitions Minister, David Lloyd George in which he made a series of four requests put to him by his friends in the Russian Supply Committee to help keep Russia in the war with Germany. Pares claims he had warned the future Prime Minister that without Britain arming the Russians themselves, things were only likely to go from bad to worse, leading almost certainly to revolution. A few weeks later, Pares claims that Sir Arthur Nicolson had called him to the Foreign Office and told him, of his dismissal. There was also to be no successor.[41]

The reasons behind Pares’ removal from the post are hazy, at best. His memoirs suggest that Buchanan had been anxious to keep him in the loop, and had supported the request of the Russian Third Army Commander to return Pares to the front. However, a series of communications unearthed in the 1980s by historian, Keith Neilson suggest Buchanan too had his reservations. In minutes recorded by Nicolson in mid-July 1915, Buchanan is alleged to have fretted that the ‘Day By Day’ accounts that Pares was feeding to the press suffered from the “besetting sin of diffuseness”.[42] It would be a mistake to draw the wrong conclusion from this. The feeling at both The Press Bureau and the War Propaganda Bureau, whose members included Robert Donald, editor of the Daily Chronicle, was that British propaganda lacked the teeth and ability to connect that characterised the output of its German rivals. What they needed were journalists whose knowledge and passion for Russia matched that of Pares but whose skills at developing narratives for public consumption and motivation were more sharply defined and capable. The direct hits that Russia and her ally Britain had suffered as a result of the Cossack outrages and the Russian’s earth scorching withdrawal from Poland had been nothing short of immense. The propaganda war was being lost, and with it the moral high ground. Allied efforts to bring America into the war has been dealt the heftiest of blows. It was generally perceived that the stranglehold that Germany had been able to place on America had been due in the main to its support from American-Jews whose diverse transcultural duties and commitments somehow binded them to their former homeland. Whilst the reality was far more complex, this was certainly the view being taken in Britain at this time.

As Britain finally awoke to the fact that the war was being fought at a narrative as much as ground level, Mi6’s liaison chief, Samuel Hoare paid a visit to Russia, reviewing the situation from the ground up and making a series of recommendations not only to improve the flow of Intelligence between its London and Petrograd offices, but to transform the way that information was being distributed to the Allied Press and to counter the overwhelming volume of successful propaganda being unleashed by Germany. To date, the only man they had in Russia fulfilling this role was Pares, whose skills and contacts could be better served elsewhere. It was probably preferable to have him monitoring the direction that support for the war was taking within the Tsarist Court and Duma that it was on the Eastern Front. If Britain was to maintain the support and the military strength of Russia in its war with Germany they would need to be ahead of the game. What was happening domestically in Russia, was now every bit as important as the progress it was making outside its borders. Pares was a trusted man with the Romanovs. If the Tsar was prepared to pull Russia out of the war it needed to know before it happened. As the signing of the Strait Agreement in June 1915 had proved, the possibilities for future trade in the Near East that would arise as a result of Allied success were simply too great to let slip. Hoare may have arrived to review the Intelligence situation in Russia in March 1916, but by July he had returned to take control, considerably ramping up of the work of propaganda specialists Hugh Walpole, Arthur Ransome, Paul Dukes and Harold Williams. [43] It was after their arrival that the informal and quasi-official body of British ex-pats working from a tiny flat at Morskaia Prospekt —eventually becoming known as the British-Russia Bureau (aka. Anglo-Russian Bureau) — was born, with Pares shuttling busily between Petrograd and England in some vague but no less critical auxiliary capacity. Explaining the advantages of the British to the Russians and the Russians to the Brits had never been more urgent. A whole new era in relations was all set to be born.

In all fairness, compared to the more mechanical and finely coordinated approach of the Germans, the British handling of propaganda was a more ad hoc and altogether more improvisational affair with amateur propagandists in abundance. For the most part it was based on voluntary organisations and individuals with often ambiguous remits. During the early phases of the war the British Foreign Office had gradually lost control of propaganda to the ‘Press Gangs’ of journalists working under the direct of Lord Beaverbrook, Lord Rothermere and Lord Northcliffe, much of it coming as a result of the enormously damaging reports produced by Pares, Robert Donald and Arthur Sturgeon of Lloyd-George’s Advisory Committee. As far as the Advisory Committee was concerned, the fairly starchy and academic pamphleteering activities at Wellington House under Masterman meant that whilst it was an impressive printing organisation it was far from being an effective propaganda agency and an even poorer distributor. The largely ‘serious works, academic in tone’ would eventually give way to a more accessible, more direct and more populistic approach. After a further review of Britain’s propaganda arrangements in January 1917, a more positive and less defensive line of attack was drawn-up. [44] The one thing that would remain consistent in Britain’s approaches throughout, however, was that recipients of official propaganda were to receive it through unofficial sources.[45] Unlike in Germany it was thought that propaganda that was both produced, consumed and distributed at a ‘grassroots’ level, and reflected the views of neutral parties, carried far more weight with the public. And it’s a climate that clearly played a part in the production and distribution of George Shanks and Major Burdon’s Jewish Peril. A huge effort had been made by the War Propaganda Bureau to recruit men from literary and journalistic backgrounds. John Buchan was an absolute specialist in pulp fiction thrillers, as was Walpole. Compelling narratives were now very much a part of the fabric. In no time at all newsworthy sensationalism replaced the need for intelligent political diatribes. Views were to be changed at an emotional rather than cerebral level. Pares may have been totally inadequate in the production of such material, but he certainly recognised their value.

Between September 1915 and January 1917, we find Pares shuttling back and forth between England and Russia. Despite his dismissal from his post as official observer reports of his experiences of frontline activities with Russian troops continue to find their way to the press, usually via the columns of the Daily Telegraph and Daily Chronicle but occasionally in Russia’s Novoe Vremya. A cursory read of his reports during this period suggests the brief he had been given had been fairly narrow in focus: keep reassuring the English that the contribution and support of the English was being warmly received by the troops in spite of their impoverished resources and Lloyd George’s continuing failure to procure them the arms necessary to restore control of the Eastern Front. There is a slight change of pace in December 1915 when Pares visits Odessa, which he describes rather bizarrely as ‘like Brighton … only four times bigger’. Published by the Liverpool Daily Post, Pares does his best to remind the city investors of the trading opportunities the Ukraine represents, jogging our memories that Odessa’s connections to England date back to the 1830s when big names in English shipping dominated its ports. Whilst a large number of the 700,000 inhabitants were Jews, the city had a healthy English colony and a local branch of the Russo-British Chamber of Commerce. [46] Sir Alfred Jones may have been dead, but the memory and his plans had certainly not been forgotten.

Back from ten days in May 1916, Pares announced plans to hold a lecture on ‘The Russian Front’ at Kings College Cambridge. A further string of lectures were carried out in the West Midlands when Pares joined his old friend R.W. Seton-Watson, Peter Struve and Harold Williams for a series of talks on the ‘National Life of the Allied Countries’ that was to be held in connection with the August Shakespeare Festival in Stratford upon Avon from July 31st until August 5th. [47] By autumn 1916 he was back in Russia. As we’ve touched upon already, by 1918 Pares had been recruited into the pro-Interventionist Committee on Russian Affairs and the Russian Liberation Committee. These cross-party pressure groups demanded full military engagement against the Bolsheviks alongside Russian ‘Whites’. We’ll come back to this in entries elsewhere in this guide.

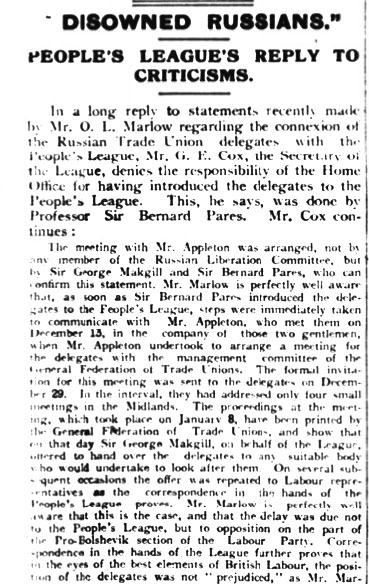

There are a couple of curiosities I’d like to toss out there, perhaps for the sake of future exploration The first is that it’s entirely possible that Pares was among the tutors of a young George Shanks at the University College London. Shanks had attended the college between 1914 and 1915 and we already know that Shanks’ uncle, Aylmer Maude had been on the staff at Pares’ School of Russian Studies in Liverpool. The other curiosity is a little more concerning; challenging as it does the common assumption that Pares was a bona fide Liberal. In March 1920 Pares is reported to have addressed a meeting of the newly founded People’s League with Section-D (Industrial Intelligence) founder George Makgill.[48] Subsequently re-named the People’s Party, the People’s League consisted of an unruly hotchpotch of disaffected Liberals and Conservatives and launched by John Bull editor, Horatio Bottomley. Oswald Mosley also once claimed to have been a member.

Endnotes

[1] Members of the ‘untitled aristocracy’ who were associated with the radical Unitarian movement, the Pares family had built a fortune around hosiery and banking businesses (Pares, Heygate & Co) in Deryshire and Leicester. Bernard’s Grandfather Thomas Pares (MP for Leicester) of Hopwell Hall in Derbyshire, served as Sherriff & Deputy Lieutenant of Derbyshire. His father John also stood as Liberal MP for Portsmouth.

[2] A Wandering Student: the Story of a Purpose, Sir Bernard Pares, Syracuse University Press, 1948, Preface Xiii

[3] A Wandering Student: the Story of a Purpose, Sir Bernard Pares, Syracuse University Press, 1948, pp.72-75. The ‘Golos Samary’ was published by moderate, right-wing Zemstvo leader, Aleksandr Nikolaevich Naumov.

[4] Mobilizing the Russian Nation: Patriotism and Citizenship in the First World War, Melissa K. Stockdale, Cambridge University Press, 2016, pp.58-59

[5] ‘The University Extension Lectures’, Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette January 17 1898, p.3; ‘University Extension Meeting’, The Times, August 7 1902, p.6. Cooke, the former British Vice Consul in Archangel, had been appointed to the post by Prime Minister Lord Salisbury (Robert Gascoyne-Cecil) in November 1899 (‘Court Circulars’, The Times, November 23 1899, p.6)

[6] The Board of Trade Journal of Tariff and Trade Notices and Miscellaneous Commercial Information 1902-12-24, Vol. 39 Issue 317, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, p.611;

[7] ‘Anglo-Russian Trade’, The Liverpool Journal of Commerce, February 13 1902, p.5

[8] The National Archives, FO 65/1647, f. 157, Cooke to Scott, May 12, 1902

[9] U.R.S.A Proceedings, vol.1, 1917-1918, London, ed. David Nutt, p.220.

[10] ‘Liverpool Chamber of Commerce: Russian Trade’, Liverpool Daily Post, February 3 1903, p.6

[11] A Wandering Student: the Story of a Purpose, Sir Bernard Pares, Syracuse University Press, 1948, p.101.

[12] ‘Russia and England, Letter to the Editor’, The Manchester Guardian, September 14, 1904, p.5

[13] ‘State of Opinion in Russia, Letter to the Editor of The Times,’ The Times, August 10 1904, p.6

[14] ‘Trade Relations with Russia’, Liverpool Journal of Commerce, November 5 1907,

[15] Eyre & Spottiswoode would also publish Pares’ English translation of Alexander Griboyedov’s The Mischief of Being Clever (Gore of Uma) in 1925.

[16] ‘Commercial Men and Russia’, Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 14 July 1909 p.4

[17] Bernard Pares, Russian Studies and the Promotion of Anglo-Russian Friendship, 1907-14, Michael Hughes, The Slavonic and East European Review , Jul., 2000, Vol. 78, No. 3, School of Slavonic and East European Studies, p.527

[18] Bernard Pares, Russian Studies and the Promotion of Anglo-Russian Friendship, 1907-14, Michael Hughes, The Slavonic and East European Review , Jul., 2000, Vol. 78, No. 3, School of Slavonic and East European Studies, p.527; ‘Duma Members in London’, Daily Mirror, June 25 1909, p.4

[19] ‘Tsar and Commercial England: The Liverpool Address’, Liverpool Journal of Commerce 06 August 1909 p.5

[20] ‘Liverpool and Russian Commerce: Sir Alfred Jones Decorated by the Tsar’, Liverpool Journal of Commerce, August 7 1909, p.5

[21] ‘Russia and England’, Liverpool Journal of Commerce, August 9 1909, p.4

[22] ‘German Colonial Minister’s Visit to Liverpool: Important Speech on German Colonising’, Liverpool Journal of Commerce, November 9 1909, p.5

[23] ‘The Late Sir Alfred Jones’, Liverpool Journal of Commerce, December 15 1909, p.5

[24] Bernard Pares, Russian Studies and the Promotion of Anglo-Russian Friendship, 1907-14, Michael Hughes, The Slavonic and East European Review , Jul., 2000, Vol. 78, No. 3, School of Slavonic and East European Studies, p.531

[25] ‘Russian Duma’s Tribute’, Liverpool Daily Post, December 15 1909, p.10

[26] ‘Russian Commerce’, Dundee Courier, December 2 1909, p.2

[27] ‘Great Britain and Russia: Closer Commercial and Political Relations’, Liverpool Daily Post, November 2 1909, p.10

[28] ‘Possibilities in Russia’, The Times, November 5 1909, p.13.

[29] A Wandering Student: the Story of a Purpose, Sir Bernard Pares, Syracuse University Press, 1948, p.101

[30] A Wandering Student: the Story of a Purpose, Sir Bernard Pares, Syracuse University Press, 1948, p.102

[31] A Wandering Student: the Story of a Purpose, Sir Bernard Pares, Syracuse University Press, 1948, p.175.

[32] ‘British official Eyewitness with the Russians’, New York Times, August 8 1915, p.2

[33] ‘The Jewish Question in Russia’, Israel N. Prenovich, The Hebrew Standard, 24 September 1915, p.12; ‘Some Recent Russian Atrocities’, The Sentinel, August 6 1915, pp.6-7 (possibly based on accounts for the New York Sun and The Day newspaper by Hermann Bernstein)

[34] ‘Russian Atrocities in Poland’, The Reform Advocate, 6 March 1915, p.119

[35] ‘Some Recent Russian Atrocities’, The Sentinel, August 6 1915, pp.6-7

[36] ‘The Russian Jews Relief Fund’, Dundee Courier, August 28 1915, p.4

[37] ‘The Jewish Problem Today’, The American Jewish World, September 10 1915, Vol. II, No.2, pp.7-8

[38] A Wandering Student: the Story of a Purpose, Sir Bernard Pares, Syracuse University Press, 1948, p.215

[39] A Wandering Student: the Story of a Purpose, Sir Bernard Pares, Syracuse University Press, 1948, p.214

[40] My Russian Memoirs, Bernard Pares, J. Cape/AM Press, 1931/1969, p.336

[41] A Wandering Student: the Story of a Purpose, Sir Bernard Pares, Syracuse University Press, 1948, pp.212-13

[42] Joy Rides?: British Intelligence and Propaganda in Russia, 1914-1917, Keith Neilson, The Historical Journal , Dec., 1981, Vol. 24, No. 4, Cambridge University Press p. 891 (citing Nicolson papers, Buchanan to A. Nicolson, 10 July 1915, PRO, F.O. 800/378)

[43] Joy Rides?: British Intelligence and Propaganda in Russia, 1914-1917, Keith Neilson, The Historical Journal , Dec., 1981, Vol. 24, No. 4, Cambridge University Press pp.888-899

[44] Wellington House and British Propaganda during the First World War, M. L. Sanders, The Historical Journal , Mar., 1975, Vol. 18, No. 1, Cambridge University Press, p.123

[45] Wellington House and British Propaganda during the First World War, M. L. Sanders, The Historical Journal , Mar., 1975, Vol. 18, No. 1, Cambridge University Press, pp.119-121

[46] Russia’s Future: Foster Trade with England’, Liverpool Daily Post, February 7 1916, p.5

[47] ‘Conference on the National Life of the Allied Countries’, Cheltenham Looker, June 24 1916, p.13

[48] ‘Disowned Russians: People’s League Respond to Criticisms’, Westminster Gazette 27, April 1920, p.12

Tweets by repeat_the_past