One of the most memorable scenes in Alan Bleasdale’s Monocled Mutineer is when the immaculately dressed Captain Percy Toplis, DCM humiliates his old pit boss and nemesis, John Thomas Todd by drilling him over and among the slag heaps of Blackwell Colliery, on the morning after a hero’s welcome and champagne reception at the Miners Club. The event, staged by the Local Defence Volunteer Force at Blackwell Cricket Ground is regaled at comic length by Percy’s friend, Ralph Ward in Bill Allison and John Fairley’s book of the same name 1. Ward then explains how the next morning Toplis awoke, and still in his fake Captain’s uniform with his fake ‘DCM’, paid a visit to Mansfield’s only professional photographer. What happens next is the stuff of legend. The photographer puts the picture on an easel in his window with a ‘carefully hand-printed notice’ bearing the name, ‘Captain Percy Toplis DCM, of Mansfield’. It’s next alleged that the photographer sent a copy of the Nottingham Evening Post, who duly published a report on the distinguished hero’s return (The Monocled Mutineer, John Fairley/Bill Allison, 2015, p.26-27).

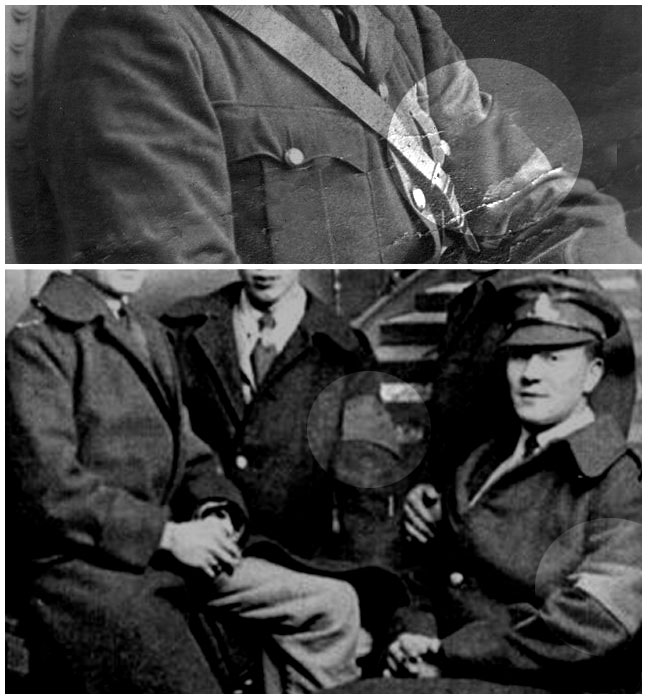

Sadly though, it’s unlikely that any of the above events actually took place. And the clues are all in the picture itself; it’s not a Captain’s uniform that Toplis is wearing and there is absolutely no sign of the DCM ribbon being worn. Percy is also wearing a mourning band.

Worth looking at in closer detail? I think so.

The DCM Ribbon and Medal is Missing

The DCM (Distinguished Conduct Medal), awarded for conspicuous bravery and second only to the Victoria Cross in terms of merit, is missing in this picture. If Toplis had gone to such audacious lengths to organize such a portrait with a local photographer’s studio, it seems a bit remiss of him not to wear the much-feted DCM whilst sitting for the picture. There’s also no sign of the Officer’s swagger stick. Fairs fair, Percy’s left side is partially obscured, but if this picture really had been staged to provide the basis of a story about ‘returning DCM hero’, I think Percy (or the photographer) would have had the presence of mind to ensure the DCM was visible, or, at the very least, angling his seat to the right.

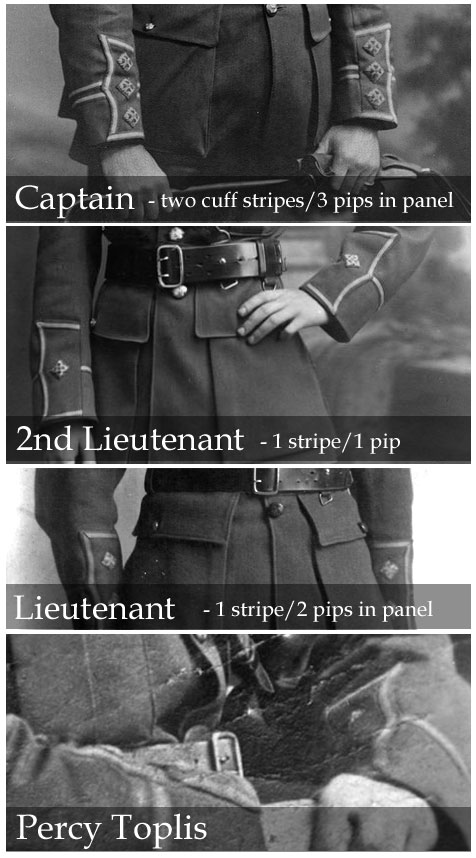

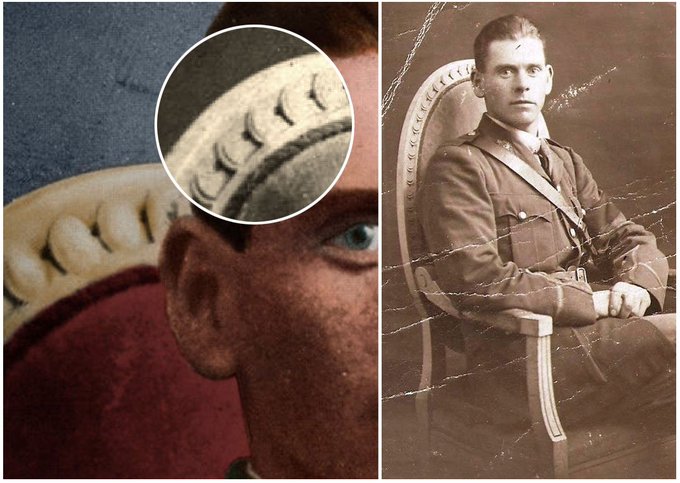

It’s Not A Captain’s Uniform

It’s terrifically unlikely that either the photographer, the Nottingham Evening Post or even Percy himself, would try to pass this off as a portrait of ‘Captain’ anybody. Why? Well, for one, it’s not a Captain’s uniform. And anybody within the local Volunteer Force, and a good proportion of the newspaper’s readers, would have recognized this fact. The picture actually shows Toplis posing as a 1st/2nd Lieutenant of the Army Service Corps. And it’s the number of pips and stripes on his cuff and sleeve that give it away.

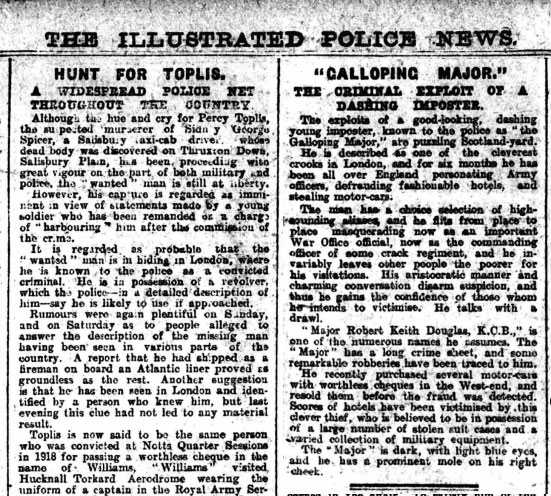

The bottom-line? It’s hard to imagine someone with two years experience in the army like Toplis making such a piss-poor effort at passing himself off as a Captain without any of the signature gear. So why come up with such a story? Well, what if encouraged by some temporary experience as an Officer (NCO or otherwise) in the immediate aftermath of Suvla, Toplis had later embellished those credentials? Or what if the entire story about Toplis impersonating an officer was a rather straightforward way of transforming a hero into a villain? Interestingly, when the Illustrated Police News originally published a report of the murder of taxi-driver Sidney Spicer, there was a story in the next column about a completely separate case that was ‘puzzling’ Scotland Yard; the so-called ‘Galloping Major’. It appears that the ‘Galloping Major’ was one of the cleverest crooks in London and had been up and down the country impersonating officers, defrauding fashionable hotels and stealing motor-cars. It sounds so like Toplis that you can’t help but wonder if some overzelaous detective had attempted to conflate the two stories, and two suspects in some way.

Did Toplis Actually Serve as 1st/2nd Lieutenant?

It’s unlikely but not impossible. The earliest reports in The Daily Mail show pictures of Toplis as a young recruit alongside those of the ‘Officer’ photo and a picture of Toplis in civilian clothes. In the first picture it describes Toplis as an Non-Commissioned Officer of the R.A.M.C. Serving as a Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) covers everything from the rank of Lance corporals and corporals to Sergeants and Staff Sergeants. Given that Toplis volunteered for the army as early as August 1914 when there were still significant vacancies to fill in the ranks, and given the enormous losses suffered in the Suvla landings (during Churchill’s utterly tragic and disastrous Dardanelles campaign) it’s just about conceivable that Toplis could have won a promotion to 2nd Lieutenant (temporarily, at least). The rank of corporal, by contrast, would have been well within his grasp. During the manhunt of 1920, his comrades in the R.A.S.C said that Toplis had told them he had once served an Officer, but had been ‘cashiered’. They said they had no reason to doubt him and the statement around Bulford was generally ‘accepted as true’. The Army’s response at that time was not to refute the claims outright. The statement that they made to the press was that there ‘was still some doubt as to whether he had actually held a commission’ (Nottingham Evening Post, 29 April 1920). The phrase ‘some doubt’ makes it sound like the exact details of Percy’s service history is not a simple matter.

The other explanation is that Toplis had fraudulently served as a Commissioned Officer? Such a successful masquerade would have been more embarrassing still.

Was the DCM Decoration So Impossible?

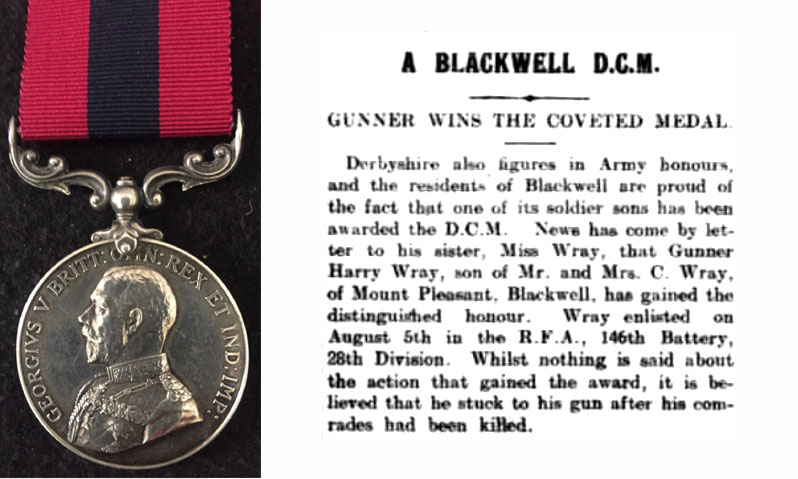

If Toplis really had won the DCM for conspicuous bravery during the Dardanelles campaign, as he is reported to have told his comrades at Bulford, then he wouldn’t have been the first working-class chap from Mansfield to have done this. The Nottingham Evening Post had already featured several such men. Harry Wray of the Royal Field Artillery was one of them. Like Percy, Wray was born in 1896 and lived a few doors away from the Toplis family in Blackwell. Also like Percy, Wray had worked at the same pit as a pony driver. Wray left for France on January 19th 1915 and served with 366th Battery, 146th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. He was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal “for conspicuous gallantry in volunteering to go out to an observation station in a very exposed position under a heavy shell fire. On arrival he found an officer and the telephonist there killed.” (Distinguished Conduct Medal (George V)(78550 Driver. H. Wray, R. F. A.). News of his decoration featured in the local Mansfield Reporter alongside another local DCM winner: Walter Mason, a stallman at Hucknall Colliery. Again the medal was awarded or distinguished conduct in the Dardanelles campaign. Local men Corporal Boot and Corporal Webster of the 22nd Field Ambulances were among others (see: Nottingham Evening Post, 30 October 1915).

Lance-Corporal W.D Fuller of the Grenadier Guards was another who had worked alongside Toplis as pony driver at Blackwell. Percy’s brother Vincent would join the Grenadiers in 1919.

No Nottingham Evening Post Article. No Picture.

Despite the legend, neither the Toplis DCM picture or the story of the champagne reception ever really appeared in the Nottingham Evening Post. In fact news of Percy’s decoration didn’t appear in ANY local newspaper during this period, despite the Mansfield Reporter listing other returning heroes among the men of Blackwell Colliery.

This leads us to the question: so where did Toplis have the photo taken?

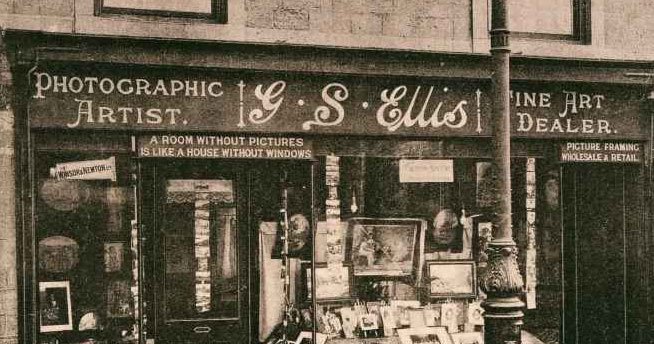

John Fairley and Bill Allison’s book says that Toplis awoke on the morning after the champagne reception and went straight to Mansfield’s only professional photographer. The only man with a photo studio in Mansfield at this time was G.S Ellis. He was also staff photographer for the Mansfield Reporter whose coverage of ‘decorated’ local pit men Corporal Fuller DCM and Gunner Wray was considerable. If Ellis would have sent the picture to any local newspaper, it stands to reason that he would have sent it to The Mansfield Reporter and not the paper’s rival, the Nottingham Evening Post.

The story is further muddled by the fact that the ‘DCM in Mansfield’ legend is said to have taken place in 1915 just as Haig was being made Commander-in-Chief British Expeditionary Forces. But Haig wasn’t made Commander-in-Chief until mid-December 1915 (Nottingham Evening Post, 16 December 1915, p.1). Prior to this it was Field Marshal John French. There’s another serious challenge to the Captain Toplis, DCM of Mansfield story. The incident is said to have taken place during a period of leave in 1915 (The Monocled Mutineer, 2015, p.24-25). Toplis had just arrived on the beaches of Gallipoli during the Summer of 1915 and is unlikely to have made it home (unless injured) until 1916.

So Who Owns the Famous Picture?

Hoping to get to the bottom of just who owns the legendary picture of the seated ‘Captain Toplis DCM’, I contacted Mike Sassi, the current editor of the Nottingham Evening Post. Mike’s response was that he was skeptical about whether the Nottingham Evening Post ever possessed the original photograph.

The photograph that you see on Wikipedia is the full wrinkled and un-cropped version. In this you can quite clearly see Percy’s jodhpurs and the base of the seat. It also possesses that distinctive sepia-tone. In every other version published through the years the image has been either been cropped or is missing his very distinctive tall-backed chair.

The first to publish the photo were The Daily Mail and the Nottingham Evening Post on Friday April 30th 1920. Both of the pictures are cropped and in both of the pictures the tall-backed chair that Toplis is sitting in has been carefully edited out. Given the relative crudity of technology at the time, it’s likely that the negative would have been required, and assuming that The Daily Mail would have gone to press the previous evening, and the Evening Post the morning or afternoon of the 30th, it’s likely that Lord Northcliffe’s fiercely anti-Socialist Daily Mail was the first to have printed the photo in the last remaining hours of April 29th or in the small hours of the morning on April 30th, and not the Nottingham Evening Post. As an evening paper, the Nottingham Evening Post would have been the second of the titles to print it.

Did Lord Northcliffe have a stake in both papers? I don’t know, but it’s interesting that both papers use the same typeface for their respective newspaper titles. Why did The Daily Mail go to the trouble of air-brushing the chair out of the published shot? Was it just more visually striking to present it this way? Or would the chair have provided a more definitive location and date-stamp for when and where the picture was taken? Was there something they were trying to hide, or was this simply a crude way of side-stepping copyright issues?

How easy was it to remove things from photos in a pre-Photo Shop world? Not easy. The earliest and most famous attempt was made in Russia.The ‘Commissar Vanishes‘ is one of the earliest and most famous examples of removing objects from a photo. As you might expect, the process was crude, laborious and almost certainly required the negative. In the Toplis shot, someone has removed the chair. In the Stalin photo it’s traitor Nikolai Yezhov that gets the chop.

The next best reproduction of the Officer photo belongs to the Mirrorpix archive (The Nottingham Evening Post and the Daily Mirror both come under Reach Plc). But in the Mirrorpix version, the jodhpurs are faded out and the image is cropped. As a result we may conclude that this is not the source for the Wikipedia photo.

So who scanned-in the image for the Wikipedia entry on Toplis? Well the entry’s history pane tells us it was Wiki-editor, Skjoldbro on May 3rd 1918. Hoping for some resolution I contacted Skjoldbro , who told me that the image had been grabbed from elsewhere online. So far, I have not even been able to find the original image-source using the redoubtable Google Image Search tool. So no answers there.

There is no other online or offline publication in the world that has used the un-cropped version of the photo available at Wikipedia, whose quality and resolution remains unmatched (despite its very distinctive speckles and creases). Despite repeated claims in several books, the photo is not at the Imperial War Museum. It’s not in the records of the Toplis inquest held by the Cumbria Constabulary and Cumbria Archives and its certainly not in the British Library. All have cropped and inferior copies of the photo available in their records, but none has anything close to the standard being offered at Wikipedia.

How did the Daily Mail obtain the original photo at the time it was went to press? A family member perhaps? The Ministry of Defence? The Police? We just don’t know.

Does the Chair Tell us Anything?

Chairs don’t speak as a rule, but I’m sure you know what I’m driving at. In an ideal world there would be have been dozens of people coming forward over the years so reveal other photos of the same said-chair in the same-said-studio. And on those chairs would be soldiers whose history and location was a little bit easier to track. And those pictures (in an ideal world) would give us the location of the studio and maybe even a time-stamp on the back.

But this isn’t an ideal world and any clues remain inconclusive.

At a glance, the chair looks fairly colonial looking. Others have mentioned that has the look of a French Louis Country chair, on account of its curved arms, oval upholstered back-rest and is solid oak frame. It also has similar French Louis upholstered arm rests too. Sadly, over the years there have been many variations on this. It’s those broad-top upholstery pins around the rim that really grab me. They certainly don’t look British so I’d venture a guess that if the photo wasn’t taken in London’s rather theatrical West End district, then maybe in France or Eastern Europe. Despite considerable efforts I’ve not been able to find anything quite so grand or decorative in pictures of serving men and women during the Great War. One thing is for sure, it is certainly grander than anything you’ll see in a typical studio in the North of England.

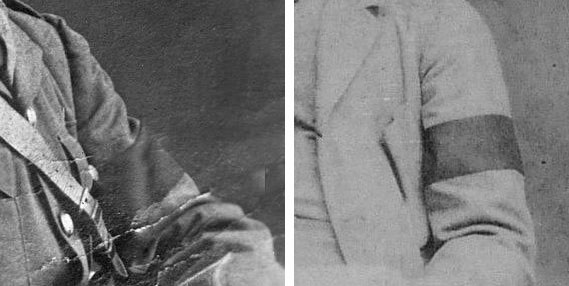

Toplis is Wearing a Black Armband?

It was a relative of Percy that pointed this out, and a what a very interesting find it is.

On his left arm Toplis appears to be wearing an armband. I’ll stop short of saying a black armband, as the sepia tone of the photo makes the colour of the band inconclusive. But there are only two real options here: it is either a black mourning band, or a ‘hospital blues’ convalescing band. When comparing the tones of another mourning band in a similar sepia picture from the period, it provides a convincing match.

Why should it matter? Well for one, the narrative that has been built around this photo is that it shows a serial and feckless fraudster masquerading as a Captain with a DCM. The addition of a respectful mourning band kind of bucks that narrative.

As you might expect, the wearing of a mourning band by a serving soldier was reasonably controversial in itself, as there were considerable issues relating to morale and patriotism. In the early stages of the war the rule of thumb was that it was permissible for soldiers on active duty abroad to wear bands for fallen comrades, but were discouraged from wearing them on leave for reasons relating to public morale. When the debate reached critical mass, the Duchess of Devonshire proposed that a white armband would ‘express the pride we feel in knowing’ that men had given their lives in their country’s cause and that we should ‘not show our sorrow’ in the usual way (The changing culture of mourning dress in the First World War, Lucie Whitmore, p.579-594).

Whilst the suggestion of a white arm band never really took off, soldiers generally resisted the temptation to wear them (depending on class). And the exceptions to the rule were really very few. In June 1916 an order was issued by R.H Brade of the War Office for all officers to wear the black crepe band on their left arm, ‘for a period of one week commencing 7th June’ to honour the death of Lord Kitchener (see H.D Davray’s Lord Kitchener, His Work And His Prestige) and The Chester Chronicle reports in April 1915 that officers wore black armbands at the funeral of Lieutenant W.G.C Gladstone of the RWF.

So there is a very small chance that the picture may have been taken during this mourning period for Kitchener, either as genuine tribute (Percy was one of Kitchener’s original volunteers) or to add a touch of authenticity to his masquerade.

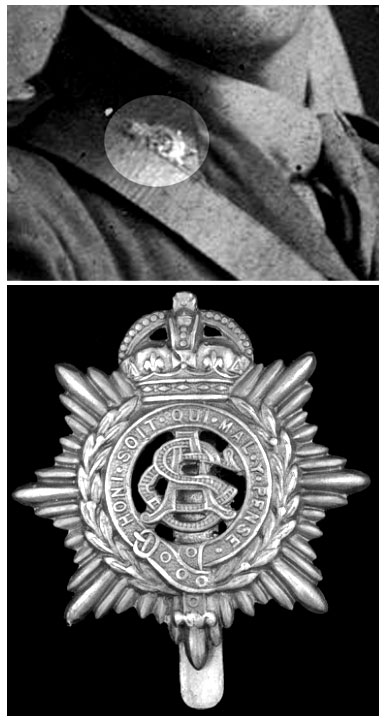

What Uniform is Percy Wearing

That’s one question we can answer; it’s the uniform of the Royal Army Service Corps. This is indicated by the collar medal he is wearing.

There has been some suggestion that Toplis may have been seconded to the RASC prior to August 1919 when he re-enlisted at Whitehall in London. Police witness (and one time suspect) Harry Fallows wrote in his formal Police Statement that Toplis could tell what was wrong with a car just by listening to its engine. If Toplis spent little more than a few months in the RASC then it seems more plausible that he picked such skills over a several year period during wartime. If Toplis was originally attached to the Field Ambulances, then drivers would be needed and Toplis may have served (on issues of protocol alone) on attachment to the ASC.

1 According to the Mansfield Press, Percy’s father Herbert Topliss served as a Captain in the Blackwell’s Local Defence Volunteer Force until his death in August 1918 (Nottingham Journal, 29 April 1920, p.1)

Tweets by repeat_the_past