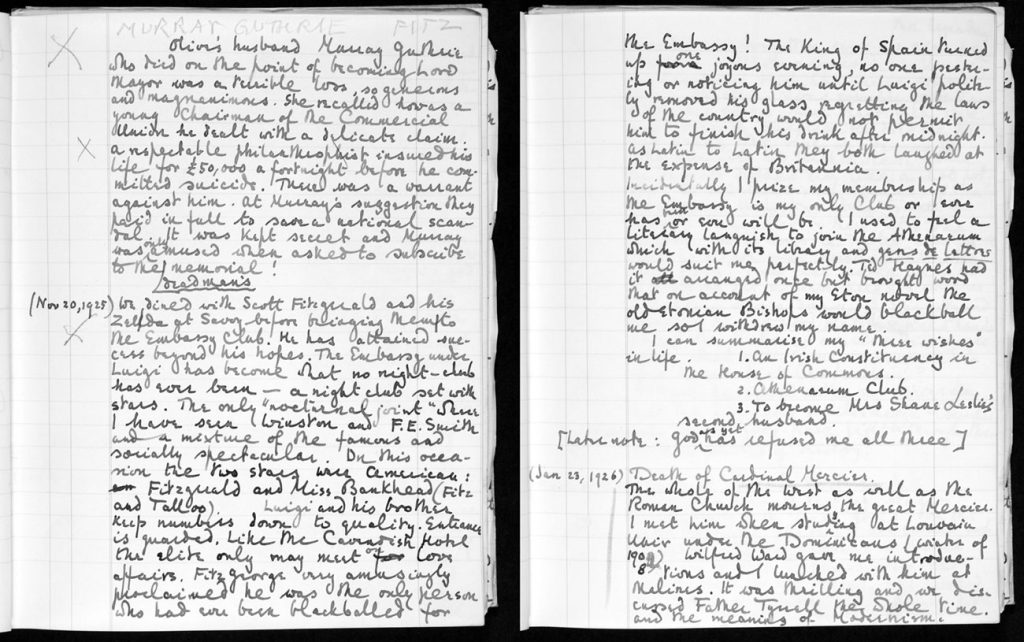

In an entry in his ledger dated November 1925 Scott mentions his second trip to London. Like previous entries it is difficult to piece together any kind of meaningful narrative from the handful of names and places he lists and much of our understanding of this trip has been gleaned from supporting diary entries made by Shane Leslie and anecdotes from Frank Swinnerton — the novelist and editor of Chatto & Windus who was hoping to secure the publishing rights of The Great Gatsby in Britain. Whilst Leslie’s diary sheds light on their riotous trip to the Embassy Club with Tallulah Bankhead, the Mountbattens and carefree minor Royals, the Milford Havens, Swinnerton tells of an amusing encounter in which Scott had grabbed his hat and fled from the publisher’s building after mistaking him for “some base hirling” and brushing off his polite queries in a brusque fashion. It appears that Scott had been anxious to meet the partners of the firm and hadn’t recognised the novelist. After twenty minutes in the waiting room, Swinnerton had the duty to inform him that neither partner was available and Scott became impatient “to the point of truculence”. It was only after Frank expressed his fondness for Gatsby, and introduced himself by name, that the penny dropped. Overwhelmed with embarrassment, Scott grabbed his hat and dashed out of the premises. [1]

On his return to Paris that month, Scott would write to his editor Max Perkins telling him all about the episode, reserving even more embarrassment for his behaviour in the nightclub: “Went on some very high-tone parties with Mountbattens and all that sort of thing. Very impressed, but not very, as I furnished most of the amusement myself.” As usual it was he booze that had triggered the offences. The group had been celebrating the success of Bankhead’s role in The Green Hat when the writer and editor, Robert McAlmon, an acolyte of Joyce, started a brawl with other members and Scott had been forced to intervene. In a letter to Ernest Hemingway, Scott confessed that he wished he hadn’t, as the beating that McAlmon got was probably well deserved, as he was such an notorious gossiper. [2]

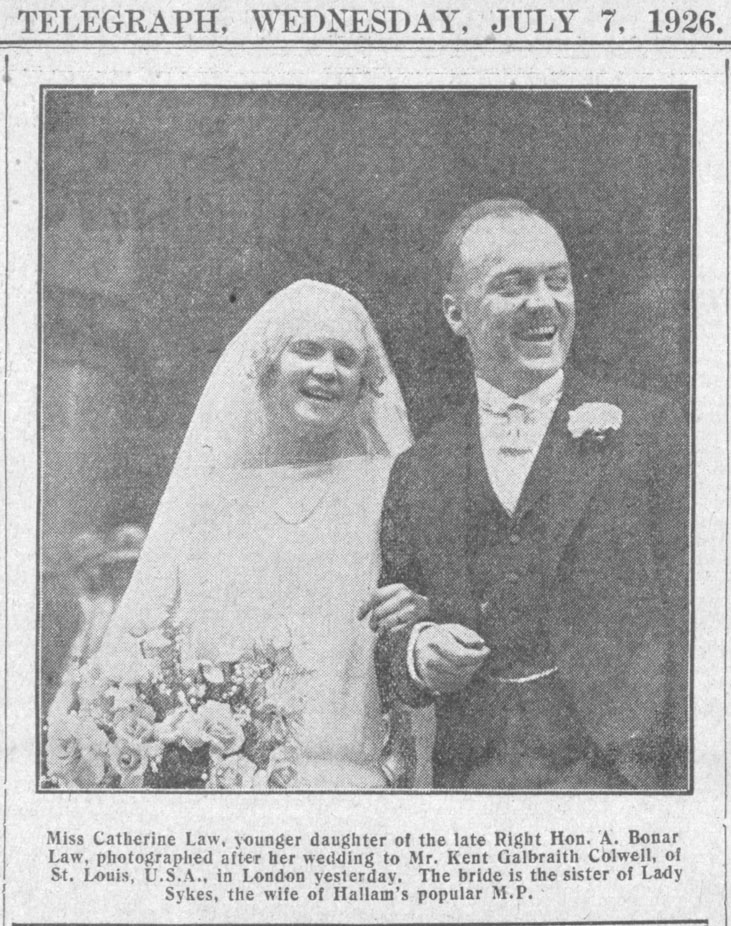

Two other names on that trip to London in November 1925 were “Colwell” and “Young”, who until now have remained anonymous to scholars. I can now reveal that the two men in question were two former classmates of Scott: Kent Galbraith Colwell and Henry Wheeler Young, known to his friends as ‘Hank’. Scott had got to know both men at Princeton, where they had been collectively enrolled in the Class of ’17. Colwell, born at the American Embassy in Paris in 1896 to the then serving US Ambassador, J. C. Colwell, former Ambassador To Britain, had been assigned to Military Intelligence in Washington as a Second Lieutenant during the war. In 1919 Kent was redeployed to Paris where he served with the American Commission to negotiate peace. After the war he had been recruited to join Scott’s brother-in-law, Newman Smith at New York investment firm, the Guaranty Trust where he worked for the next few years. After a brief spell in Belgium he had been appointed manager of the Kingsway Office in London, where he had been performing lesser duties since October 1920, occasionally shuttling back and forth to Brussels. [3] On an ocean cruise in 1925, Colwell met Catherine Law, daughter of Andrew Bonar Law who had served as British Prime Minister from October 1922 to May 1923. After Law’s sudden death in October 1923, Catherine had been made a ward of newspaper magnate, Max Aitken, 1st Baron (Lord) Beaverbrook. The couple married in September 1926, whereupon they moved back to the United States. [4]

The more freewheeling’ Henry Wheeler Young, an amateur musician, was the son of Lawrence A. Young, one of Chicago’s best known lawyers. His grandfather was General Bennett H. Young, Confederate raider and man of many legendary adventures. At the time that Scott met up with the pair in London, the young science graduate was working with a London-based advertising company. Henry (known as Hank) makes his first appearance in a letter from Zelda to Scott in March 1918: “Hank Young arrived yesterday, to see me parade around in fine feathers. He was just telling me how proud of me you’d be.” [5] News of Scott, Young and Colwell’s London reunion was duly reported in the Princeton Alumni: “Kent Colwell, 1917 correspondent for Great Britain, the continent and points south and east, writes briefly of himself and forwards letters from Scott Fitzgerald and Hank Young”. [6] Colwell proceeded to inform his readers that he had just been in Glasgow and Liverpool for a few days on business. There were many American plays in theatres and among those he was keen to recommend were Is Zat So and several other Shubert productions. News from Scott was that he was going to spend spring in the Pyrenes near Pau before heading down to Nice on the Riviera. Owen Davis dramatization of The Great Gatsby had just opened in New York and looked set to be a hit. He also had a new book of short stories coming out: All the Sad Young Men. Hank Young had spent the immediate post-war period with the American Charge D’Affairs in Santiago, Chile before finding employment with Stilwell & Co Ltd in London’s Charing Cross. Like Colwell, Young married after a whirlwind romance on a transatlantic liner. News of his wedding at the Hotel Ritz in Paris in August 1925 made it to page three in the European edition of the New York Herald. [7]

On November 14 1925 Scott was among thirty Princeton graduates who gathered for a reunion dinner at the Restaurant Laurent in Paris. [8] The Princeton Club dinner had been organised by Major Edward Royal Stoever, the new club’s secretary. Stoever, had, like Scott’s brother-in-law, Newman Smith, played a key role in Herbert Hoover’s American Relief Administration during its operations in Paris during the war. After a stint at the American Embassy in Constantinople and Crimea, 1919 had seen him reassigned to America’s Peace Commission in Paris where he worked alongside Scott’s friend, Kent Colwell. In light of the pair’s proximity to Scott in London, one might well wonder if Young and Colwell had joined Scott and Stoever at the club’s reunion dinner that week. [9] Stoever, who famously wed White Russian princess, Olga (Demidoff) Troubetzkoy in France in 1915 was subsequently appointed US Trade Commissioner in London. A bizarre story in 1923 had told how having fallen on hard-times, the princess had been forced to seek “other means of making a livelihood” at Chez Madame Hélène, who ran a high-class brothel at 28 rue Brey that was popular with diplomats at the various embassies on the city’s Right Bank. According to reporter, Basil Woon, the princess had stolen jewels, valued at 125,000 francs, from Ned G. Hillsburgh, an American sports promoter. The court heard that Olga had agreed to be Hillsburgh’s ‘companion’ for the sum of $1000 a day with half of the money going to Madame Helene. The princess further alleged that the jewels had been given to her in lieu of several payments. The 21 year old Olga was later cleared of all charges. [10] Stoever’s adopted son, Sergei, the child that Olga had with her first husband, Prince Sergei Petrovich Troubetzkoy (1881-1965), would go on to serve in the 7th Regiment and Army Intelligence during WWII. [11] The Princeton Alumni reported Stoever’s death in 1930. [12] During the late 1920s, Zelda Fitzgerald would enrol at the ballet school of Lyubov Egorova-Trubetszkoy, the wife of the prince’s cousin, Nikita Sergeevich Trubetzskoy, an influential member of the White Russian exiles who had fled to Paris in the aftermath of 1917 Revolution. In a letter to Zelda written in the summer of 1930, Scott laments that he was obliged to ruin a story that he was writing to take the Trubetzskoys to dinner. [13] Lyubov Egorova-Trubetszkoy would later provide an assessment of Zelda’s dancing proficiency in a report requested by her psychiatrist, Dr Oscar Forel. [14]

[1] Figures in the Foreground, Frank Swinnerton, Doubleday, 1964, p.158

[2] ‘To Ernest Hemingway, November 30, 1925’, Life In Letters, p.130.

[3] ‘Promotion for Kent G. Colwell’, Trust Companies 1924-11: Vol 39 No. 5, p.654; Catalogue, Princeton University, One Hundred and Seventy First Year, 1917-18, The University of Princeton, NJ, 1917, p.454 (Colwell), p.456 (Young), p.486 (Fitzgerald). The trust was located next door to the new premises of the Air Ministry (formerly at the Hotel Cecil).

[4] ‘St Louisan to wed Miss Catherine Law’, St Louis Dispatch, April 14, 1926, p.23; Weddings, Vogue September 1, 1926, Vol 68 Iss 5, p.102; Ocean Voyage Ends in Marriage, New Castle News, August 29, 1925, p.7

[5] Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda, Bloomsbury, 2002, p.19

[6] Class of ’17, Princeton Alumni Weekly, Volume 26, No.26, p.718; https://princetonarchives.tumblr.com/post/646638488026054656/throwback-thursday-front-and-center-in-this ; Young’s father Lawrence, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/187623869/lawrence_andrew_young ; Princeton Alumni Weekly. United States, Princeton University Press, 1921, p.130

[7] ‘Four Day Courtship at Sea Culminates in Paris Wedding’, New York Herald Paris, August 30, 1925, p.3

[8] ‘Princeton Club Dinner’, New York Herald Paris Edition, November 8, 1925, p.4

[9] US Relief Delegate to Tell About Europe, Edward R Stoever to talk about Europe Mission, The Philadelphia Inquirer, 22 June 1920, p.12; ‘Paris Club Offers Prize’, The Daily Princetonian, December 10, 1925, p.3

[10] ‘Accusation against ex-Princess not just, Court Says’, Chicago Tribune, Paris Edition, March 15, 1923, p.1

[11] https://www.geni.com/people/Prince-Sergey-Trubetskoy/6000000174810314834

[12] Edward Royal Stoever, Class of 1908, Princeton Alumni, November 14, 1930, Vol. XXXI, No.8, pp.214-215. Olga was the daughter of the former Governor of Kiev, Paul Demidoff.

[13] ‘To Zelda, Summer, 1930’, Dearest Scott, Dearest Zelda, p.65

[14] Some Sort of Epic Grandeur, Matthew J. Bruccoli, pp.357-358