In Part One of this look at Scott Fitzgerald’s trip to Europe in the summer of 1921 we discovered that when the author left for England on the R.M.S Aquitania on May 3rd he was joined by some of the most prominent men in New York and Washington including the new American Ambassador, George Harvey, Colonel Edward M. House, Henry White and Otto H. Kahn. The American press had described the trip as a ‘spring exodus’. Scott would arrive in London in what would prove to be a make or break time in British and American relations. Here’s what happened.

The kind of bigotry shown by Scott in his letter to Edmund Wilson was pretty appalling by any standards, but it was still only a faint echo of the shrieks and objections coming from the ‘glitter and gold’ folks he was meeting in London. In these people, the prejudice was more persistent and ingrained. During the couple’s second stay in the city, phrases like ‘the white man’s burden’ are likely to have been bouncing off the walls of the hotel’s restaurant, bar and lounge, morning, noon and night. The 1,000 room Hotel Cecil was a grand and imposing brick and stone building on The Strand. It had just been reopened after being requisitioned for the war effort in 1917. For the next three years this ten-story landmark hotel with 800 rooms would serve as the headquarters of Lord Rothermere’s newly formed Air Ministry. It was here that Scott had furiously scribbled off his rather ’violent’ letter to Wilson dismissing the entire continent of Europe as a fleet of “tottering old wrecks”. It was also in London that Scott had been introduced to an illustrious parade of British dignitaries that included Lady Randolph (Jennie) Churchill — the New York-born mother of Britain’s Secretary of State for the Colonies, Winston Churchill — and the Marchioness of Milford Haven, the daughter of Grand Duke of Hesse and granddaughter of Queen Victoria [1]. It is often speculated that it was Zelda’s friend, Tallulah Bankhead, Britain’s favourite American stage-star, who had made the introductions, but if a diary entry made by Shane Leslie during Scott’s next trip to London in 1925 is anything to go by, the more likely explanation is that Scott had been introduced to Churchill and the Milford Havens by Leslie, the former British diplomat who was now acting as Scott’s literary mentor at Scribner.

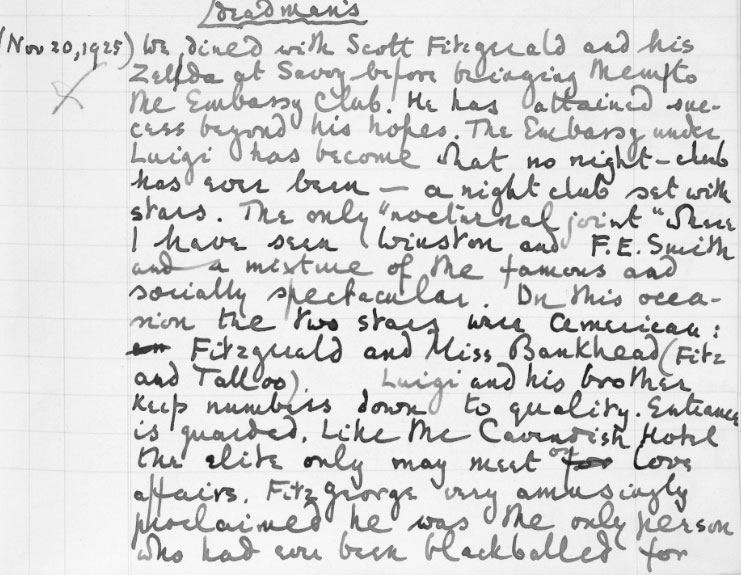

On November 20th 1925 Leslie had recorded in his diary that he had entertained Scott and Zelda at the Cavendish Hotel before taking them on to the Embassy Club on Old Bond Street. In the carbon typescript of his 1938 memoirs, Leslie claims that it had been the Embassy Club where Scott had been introduced to Winston during his first trip to London in May 1921. [2] An entry from Scott’s ledger dated June 1921, likewise mentions a trip to the Cavendish Hotel. A later one dated November 1925 confirms a trip to the Embassy Club, although it makes no specific mention of Winston, nor anybody else for that matter. The entry in Scott’s ledger for May, June and July 1921 has led some biographers to conclude that Scott had been lodging at the Cavendish Hotel, but this is almost certainly not the case. If Zelda’s memories of meeting Bob Handley in the “gloom of the Cecil” are correct and the chronology of Scott’s ledger is accurate (‘June 30, London … Bob Handley’) then the couple resumed their place at the Hotel Cecil and not the Cavendish Hotel after returning from France and Rome at the end of June. Zelda mentions the stay in a letter to Scott written in September 1930 in which the trip with Leslie to Wapping and the Randolph Churchill are also recalled. [3] Zelda’s memories of the trip are supported by Scott’s letter to Edmund Wilson written after his return from France and Italy which, according to Matthew J. Bruccoli, had been scrawled on Hotel Cecil stationery. [4]

Run by the celebrated ‘Queen of Cooks’, Rosa Lewis, the Cavendish Hotel was more popular for its food than for its rooms. Winston’s mother Jenny had employed Rosa in her service and the cook had retained a close relationship with the Churchill and Windsor families well into the 1920s. The Embassy Club was likewise frequented by Leslie, Winston and the Milford Havens. In his diary entry in 1925, Leslie recalls that it was during this second trip to the Embassy Club that he had shared with Scott and Zelda his main aims in life. Among his hopes were an Irish constituency in the House of Commons, membership of the less glamourous but infinitely more prestigious, Athenaeum Club and “becoming Mrs Shane Leslie’s second husband”, a caustic aside on the fragile state of his marriage to Marjorie at that time.

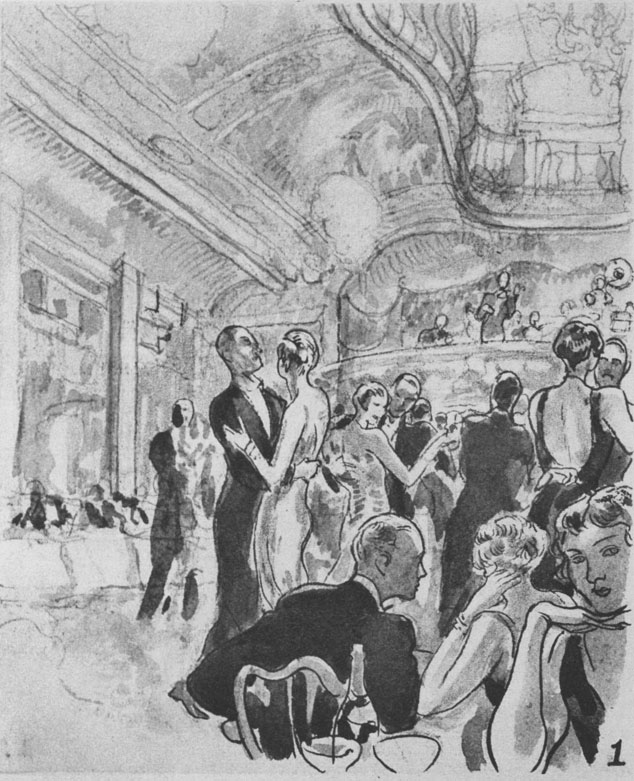

The Embassy Club, run by Italian restaurateur, Luigi Naintre, was known for its wild parties. Shane remarks in his letter that under Luigi, The Embassy had become what no London nightclub had ever been in the past: “a night club set with stars”. Edward VIII would famously describe it as the “Buckingham Palace of night clubs.” Slipping into the Bond Street building after dinner parties around midnight, one would glide through the large swing doors and down to the most luxurious of basements and a whirly-gigging dance floor, set on all side by mirrors. On a balcony on the far side of the room would be the band. For the next four hours the rules of the Old World would be wickedly suspended. Press Lords would mix with princes and actors, writers and hangers on with ambassadors and politicians. Scott and Zelda would have melted into the place just perfectly, all boundaries, imagined or otherwise, collapsing in a hypnotic cloud of smoke and a swirl of tassel dresses and dazzling sequins. For those who wanted something totally lawless, you could leave and head over to the 43 Club in Soho, but if you were prepared to be discreet, the same blistering quantities of cocaine and heroin could be consumed in the booths and in the rest rooms. [5] An entry in Shane’s diary reveals that it was “the only nocturnal joint” that he had seen his cousin Winston and his good friend Frederick Edwin Smith, the First Earl of Birkenhead, mix it up with “the famous and socially spectacular.” On this occasion, the stars were both American: Scott Fitzgerald and Miss Bankhead (“Fitz and Talloo”). If someone special was dining, Luigi and his brother would deliberately kept numbers down “to quality” and the entrance would be preciously guarded. Like the Cavendish Hotel, The Embassy Club was where the elite would meet “on love affairs”. Beneath its dangling chandeliers and lavish corniced ceilings, Scott and Zelda would have probably found themselves fox-trotting to tunes like Beneath the Burmese Moon, led by bandleader, Bert Ambrose and the Embassy Club Orchestra — a personal favourite with Edward, Prince of Wales. According to his diary, Shane found it impossible to conceal his joy at seeing the couple: Scott had “attained success beyond his hopes” and was obviously delighted he had come to London. [6]

Embassy Club

In a letter to his friend, Ernest Hemingway, Scott refers to rumours of an ‘English orgy’ the couple were alleged to have gone to in town. The author makes a half-hearted effort to persuade his friend that it wasn’t what everybody thought and jokes that it could possibly be traced to the ‘entertainment’ put on by Leslie. The next bit was more mischievous. Any gossip that Scott might have drunkenly shared about the club’s most illustrious patrons, the Windsors and Mountbattens, should by rights be treated as “fiction”. In 1925, New York’s Boni & Liveright published Rosa’s memoirs, The Queen of Cooks — and Some Kings. Their Embassy Club companion, F. E. Smith would die of cirrhosis of the liver in 1930.

Leslie’s place in the lofty firmament of Anglo-Irish and American relations had been firmly assured from birth. As we’ve seen already, Shane’s first cousin was Winston Churchill, son of New York’s Jennie Jerome — more commonly known as Lady Randolph Churchill. [7] Shane’s mother Leonie was Jennie’s sister and his brother-in-law was the legendary US Congressman, William Bourke Cockran. In his 1936 memoirs, American Wonderland, Leslie would describe Cockran as “the last of the Irish orators.” His life in America had read like a romance. He had arrived in New York from Sligo in Southern Ireland without a penny to his name yet had walked down Broadway “like a King”. After training as a criminal lawyer, the young Cockran had never looked back and within years he had become the sounding board of Ireland in America. His magnificent oratory compelled and entertained, instructed and commanded even the more stubborn of rivals, regularly turning his opponents onto causes that in other hands would have been already lost. Leslie recalls that he could play an audience “like melodeon”. Hearing him once and you were under his spell — cousin Winston included. [8]

Like Leslie, Cockran was an Irishman with a pro-English bias. On one memorable trip to the Orient in 1905, the eldest daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt would joke that Cockran was an “Anglophile” in public but a veritable “Anglomaniac” in private. Representing the Tammany Hall stronghold of Manhattan’s East Side, New York’s 12th Congressional district, Cockran’s sympathies were with its thriving population of immigrants. This, in addition to his tireless support of Free Trade and Irish Home Rule, had made him America’s patron saint of hopeless causes. As one time President of the America’s Immigration Protective League, Cockran would launch a heroic crusade against the plans of the McKinley Administration to introduce the first serious restrictive measures on US immigrants. [9] If anybody understood prejudice, it was Cockran, whose devotion to the Irishman’s pursuits of politics, horses and the Catholic Religion had put him up against a lifetime of contempt under America’s protestant Old World families.

As President of the Empire Council it’s almost certain that Winston would have had attended the various meetings of the Empire Council as it prepared for the conference ahead of them at the Hotel Cecil. On the balconied terraces of the hotel’s dining hall overlooking the Victoria embankment of the Thames, one can almost hear Winston in his usual bilious fashion remarking on the parallels that could be drawn between the recent disturbances in India and the dire predictions being offered in Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color, then being touted by London newspapers as one of the ‘most notable books’ of the day. [10]

A Special Relationship

Scott and Zelda’s arrival in London in May 1921 had come as a critical time in Anglo-American relations. Warren G. Harding had been sworn in as the country’s President on March 4 and had immediately set about uncoupling the United States from the League of Nations matrix. At his inaugural speech in Washington, Harding reassured his people that America would play no part in the creation of a “world super-government”. America would advance along its own trajectory, detached from all “political commitments” and “economic obligations” to Europe. “We do not mean to be entangled”, he affirmed. It was the President’s belief that the progress of the American Republic, both spiritually and materially, had proved the wisdom of non-intervention in “Old World’ affairs. Harding was confident of America’s inherent gifts for shaping its own destiny, and after the thirty months of turmoil during the war, was anxious to have no further part in directing the destinies of the “Old World.” Every effort would now be made to exercise America’s national sovereignty and resist on every point the “reversion of civilisation”. [11] Colonel George Harvey, the brand new Ambassador to Britain who Scott and Zelda had sailed into Southampton with on May 10th, was here to enforce that new position.

Harvey’s relationship with the former President Wilson had been damaged irrevocably two years before, when sensing Harvey’s utter contempt for the peace negotiations in Paris, Wilson had accused Harvey of being in the thrall of Wall Street bankers. The same claim was immediately turned round on the President. It was the end of a very special relationship. Harvey had been among Wilson’s first political sponsors. Back in 1910, it was Harvey who had encouraged the 54 year old Wilson, then serving as President of Princeton University, to take up political life and stand for the Governorship of New Jersey. But by January 1919 Harvey was one of Wilson’s most uncompromising critics, disapproving in the strongest possible terms with the left-leaning ex-President’s Fourteen Point Peace Agreement. The war and its outcome had steered Harvey from being a loyal and longtime Democrat into a stubborn, tough-talking Republican, preferring “American Nationalism to Rainbow Internationalism”. [12] Luckily for Leslie, the one thing that Harvey liked to be seen as firm on was Irish Home Rule. Just a few weeks before Harvey set sail for England, the Boston Globe wrote a puff piece on his deep Hibernian roots and his consistent friendship with Ireland, wondering if he was to likely to repeat a speech he had made on St Patrick’s Day some ten years before. [13] The arrival of Harvey in London just as the Lloyd George government was thrashing terms for the formation of an Irish Republic was certainly no coincidence.

Such was Harvey’s enthusiasm for the post of Ambassador that he had suspended his work as editor of the North American Review and the New York World for the two-year duration of his stay in London. And it isn’t difficult to understand why. In March 1919, Harvey had launched a blistering attack on the League of Nations covenant that was presently under discussion at the Peace Conference in Paris. Addressing a crowd of Chicago bankers at a Saint Patrick’s Day dinner at the Columbia Club in Indianapolis, Harvey tore into the scheme with astonishing abandon, demanding “square resistance to the active propaganda now going on, on behalf of the League of Nations” that was backed financially by “Anglo-Americans”. The backers of this “sinister league”, Harvey assured them, wanted nothing less than to transfer the sovereignty and independence of the United States of America to “autocratic” outside nations. The most sacred traditions of the Republic were under threat. Unless they acted now, it was only a matter of time before America would become the ‘catspaw’ of Europe. [14] Heading across to England on the RMS Aquitania with Scott at the beginning of May, Harvey could have turned around on the deck that week and found in any direction the most powerful American Anglophiles purring away beside him.

Scott’s trip to London was marked by no small amount of sadness. Unbeknown to many, he had his own personal grievance with the Peace talks in Paris two years before and an axe to grind with Britain’s former US Ambassadors, Cecil Spring Rice and Lord Reading. In January 1919 Scott had learned that his dear friend and counsellor, Father Sigourney Fay had died suddenly in New York. Still at Camp Sheridan and working furiously on revising the drafts of his first novel, Scott had received news of Fay’s death in a telegram dated January 12th from Claudius Edmund Delbos, the man who had supported Fay on the Board of Guardians at the Newman School for Boys in 1914. [15] Immediately, Scott contacted their mutual friend, Shane Leslie. He was desolated by the news and shared his despair with Leslie. Fay had been the “best friend” in the world he had ever had, a surrogate father, and the first to have encouraged his literary aspirations. The news had hit him hard. Sensing that Scott risked slipping into a deep depression, Leslie wrote back from New York, trying to lift his spirits. As miserable as they both felt, they “still had the church” and for that reason they should keep their “lamps alive.” [16] Whatever light that Fay had brought into their lives, had to keep shining.

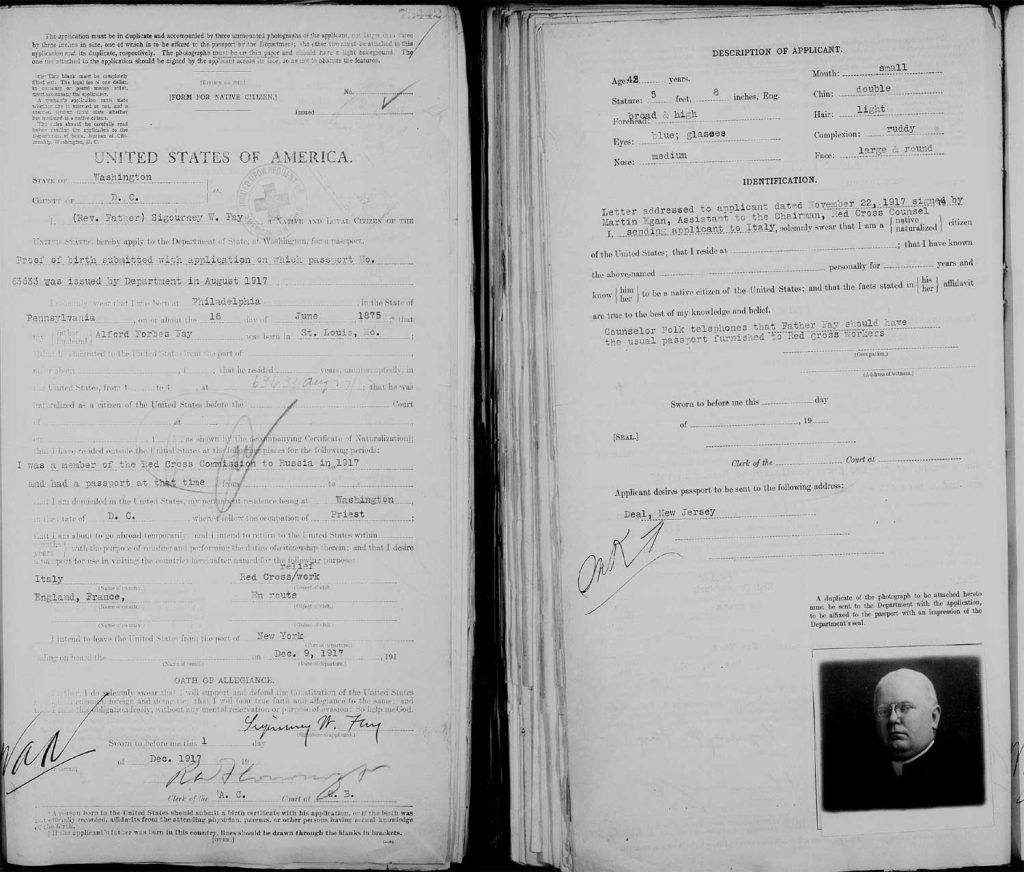

If he was ever in New York, Leslie suggested Scott pay him a visit. He was going to be there for several more weeks. The Irish Home Rule supporter, Sir Horace Plunkett was due to arrive in the country and Leslie was anxious to witness developments. The situation in Ireland was growing graver and more complex by the day and as a result was delaying the reconstruction and rapprochement of Europe. On the eve of his trip to America in January, Plunkett had told reporters that the “future of civilisation” depended on the ongoing cooperation between the United States and the British Empire, and that the various misconceptions about the crisis were threatening to tear the two countries and the peace process apart. Upon his arrival, the Sinn Fein leaders in Boston branded Plunkett a British “secret agent and propagandist”. According to them he had always been an enemy of the Nationalists in Ireland and the Irish in Boston and New York would be well advised not to be taken in by such a ‘hoax’ home ruler. [17] Fay’s death had arrived a critical time. For the past few months the priest had been passionately engaged in trying to negotiate a seat at the table for the Vatican — and the Irish — at the Conference in Paris. He had died on the eve of a trip to London during which he would have made his case to the allies. Shortly after Plunkett’s arrival on the White Star line, President Wilson was facing mounting pressure over a statement he was rumoured to have made at a White House dinner conference in which he is alleged to have said that the breakaway Irish Nationalists would have ‘no place’ and ‘no voice’ at the Peace Conference. The claim was strenuously denied by the President’s private secretary, Joseph Tumulty. [18]

Fay, arguably one of the wealthiest priests in America at that time, had been fated to have a meteoric rise through the ranks, thanks in part to his charismatic personality, his first-class intellect and his formidable range of friends in the upper echelons of New York and Washington society like the Astors, the Vanderbilts and the Chanlers. At this point in time, President Wilson’s Catholic Private Secretary, Joseph Patrick Tumulty was viewed by the Protestant contingent of the anti-Leaguers as a scheming Trojan horse working to obligate America to the Holy Roman Empire. ‘Square action’ journals like The Menace, were on hand to back up these beliefs with more sharply tapered conspiracy theories. It was their belief that the Pope’s support for the League of Nations was to build a New World Order every bit as wicked as ‘Godless Communism’. Readers were duly warned that it was the first stage in the Vatican’s bid for global domination as a collectivist super-state. For the vast majority of right-wing populists and Paeloconservatives, the Pope was being recast as a dangerous False Prophet plotting his apocalyptic rule. In their grotesquely distorted world-view, the League of Nations was nothing more than a Europe-led conspiracy set-up to retard American growth and freedom. Poor old Father Fay had found himself battling the thrashing, mad Cyclops figure that was the nascent conspiracy industry, and not just in Washington, but in Rome, where rumours of German spy rings were crashing all hope of diplomacy. And with the weight of responsibility being heaped on his shoulders by British Ambassador Cecil Rice Spring, and his successor Lord Reading in Washington, the whole thing was having the worst possible impact on Fay’s health. Already weakened by his trips to Rome and the stress placed on him by a bewildering series of missions and propaganda efforts for the Vatican, Britain and the White House, Fay picked-up the Spanish Flu.

Joseph W. Barry, the Dean of the Nashotah House seminary in Wisconsin had once described Father Fay as “the most perfect example” that he had ever known “of the will to believe.” [19] The titanic efforts the priest had poured into reconciling the Churches of the West with those of Russia had led to the priest’s first nervous breakdown in 1908. But if we learn anything from Jay Gatsby, it’s that “living too long on a single dream” can cost you everything. For over two years Fay had put every ounce of energy into pushing the allied cause, a prolific and painstaking campaign that would culminate in the sensational The Genesis of the Super German, a 1000-word attack on the “insidious propaganda” being carried out by Germany and their devious attempts to dig their “tentacles” deep into the heart of the Church. The hysteria wasn’t confined to Fay. In May 1917 the Protestant press of America had been delighted to report on the exposure of a German spy network operating at the heart of the Vatican. [20] The news followed the arrest of Monsignor Rudolph Gerlach, a Bavarian priest who had been serving as chamberlain and confidant to Pope Benedict XV. The papers went wild: “Pope’s Secretary Caught Red-handed Directing Three Plots of Intrigue” screamed the leading conspiracy journal, The Menace. It was all the evidence they needed of a dastardly web of intrigue surrounding the friendship between the ‘Black Pope’ of Rome and Kaiser Wilhelm. [21] By February 1918 the Holy See was beginning to be regarded by many Americans as a veritable ‘spy nest’.

Until this point, the Church had made every possible effort to maintain an official position of impartiality in the war. Fay and the allies immediately sensed the hand of ‘the boche’ themselves in the rumours. Fay’s blistering article did its best to restore some balance and trace the root of the seditious attacks on the Vatican and its clergy to German propaganda machine. In a total break with convention the Pope was left with no other option than to clarify its position on the war and his support for the liberation of Jerusalem by the allies. The battle lines were being drawn and the rules of engagement hastily redrafted. The Fay family were no stranger to battle. Fay’s father had been the decorated and respected Lieutenant-Colonel Alford Forbes Fay of the US Army — a direct descendent of the heroes of the American Revolution. Although his instinctive response had always been to repair relations and soothe injury, Fay was not in the least bit phased by the challenge. That isn’t to say his intervention hadn’t been controversial. The article he wrote was a divisive piece all around, and it would be difficult to envisage that it had the support of everyone at the Vatican who had worked so hard in projecting neutrality. A role at the peace table was one thing, but portraying the German nation as an army of Nietzschean ‘supermen’ intent on destroying the world is likely to have chimed more favourably with the British Foreign Office and the US State Department than with the broad and argumentative community of pontiffs in Rome.

One can only assume that Fay’s article had been the result of the fractious negotiations going on within the very fractured papal hierarchy. The Vatican had already been forced to defend the credibility of their position on the war after Fay’s colleague, Monsignor Bonzano had been accused of pushing pro-German attitudes and failing to accurately reflect the position of Wilson and America. Everybody everywhere was looking for reliable intelligence on the true status of feeling, and everybody everywhere was doing their level best to distort it, or so it seemed. Things were getting seriously out of control. Even the Saturday Evening Post had begun to stir the pot with a highly piece by Elizabeth Frazer on the work of the Red Cross in Italy. Despite the mounting pressure, Pope Benedict XV dug in his heels and avoided endorsing either side. Fay was left with very little option but to set the record straight. His next piece, The Voice of the Vatican, published in September by The Chronicle, made every attempt to rescue the pontiff’s reputation, defending as did, quite vigorously, the position the Church had taken on German autocracy and rejecting any notion that the Pope and his clerics were colluding with ‘German spies’. [22]

The English diplomat, Robert Francis Wilberforce, who had been specially appointed to support Fay’s work from within the British Mission in Rome, would write to Shane Leslie in May 1918 saying that Fay’s stay in Rome had been a “brilliant success”. [23] If anybody was capable of articulating this common language and shared ideals of the two nations it had been men like these — not spies as such, but well-oiled keys of information who could provide a mirror into the soul of the Irish-American-Catholic situations. The ‘special relationship’ that Winston Churchill spoke of in 1944, had started here, ably supported by understanding Ambassadors to Britain like Bryce and Spring-Rice — men who were thoroughly acclimatized to the “peculiar social atmosphere of Washington and America.” [24]

Wilberforce had been among several influential figures, Leslie, Fay and Gibbons included, who had taken editorial control of the Dublin Review during the war in an effort to make Catholic thought and feeling in America better represented across the world. Sharing its new manifesto with its readers at the end of 1916, the respected Irish quarterly had explained how at this time of “great crisis in Christendom” it had been necessary to mobilize “the fighting forces of Catholicism”. The union that was in the “strength of great enterprises” would be sought and found in the journal’s pages: “the green cover proper to its name will stand for something more than its green old age.” [25] Fay’s articles however, created a storm among German Americans. As letters of complaint flooded into the newspapers, the real world was bleeding in. The “old warm world” that Fay had known back at Newman was disappearing. The war was taking its toll.

A Light Goes Out

In the last week of December the pan had really started to boil. America’s future Ambassador to England, George Harvey had addressed the 113th New England Society in New York and put the knife in the League of Nations. Harvey didn’t mince his words: American had bigger problems in Chile and Peru and should focus its attentions on the those. The quest for ‘everlasting peace’ was an indulgence it couldn’t afford. America, he growled, was hell bent on pursuing the most “entangling” of alliances that would lead to war, not peace. [26] The following day, Woodrow Wilson had sailed for Europe, determined to reassure the British and the France that he remained totally committed to the project. Joining Lord Bryce and Viscount Grey at the American Embassy in London, Wilson said how “delighted and stimulated” he had been to see “growing and prevailing interest” in the League. He was confident that the series of conferences that would follow in Paris would fulfil the various moral obligations it had to the world. Back in America it was felt that the most conspicuous advocates of the League were now the Pope and President Wilson. On January 10th 1919, just eight-days prior to the conference, tired and exhausted from months of vital travel, Fay succumbed to pneumonia and died during as he awaited passage to London at the Rectory of Our Lady of Lourdes in New York. He had arrived at the rectory in the previous evening and within hours was feeling ill. It had all happened so quickly. Any progress he had hoped to make in getting the Vatican a last-minute place at the table at the Peace Conference was left hanging. For Fay at least, the battles were over. He was 47 years old. [27]

Six days before his death, Fay’s nemesis, The Aurora Menace had reported on a speech that Fay had given at Carnegie Hall just four weeks earlier in which he pledged his backing to the creation of the League of Nations. It was the editor’s belief that the ‘cruel engine of oppression’ that had been set-up by the Holy Roman Empire some several centuries before was now “hell-bent” on extending and perpetuating its autocratic rule. Despite its new, peaceful vestments, it was still the ‘champion of absolutism’ that it always was. The ‘days of Popery and coercive leagues’ were numbered, the paper warned. [28] As Fay lay dying in his bed in New York, President Woodrow Wilson was steaming back across the Atlantic after an emergency meeting in Rome. On the afternoon of January 4th he had been received at the Vatican by Pope Benedict where he and the Italian King had reaffirmed their support to the League of Nations and plans for a British Mandate in Palestine. There was also another new threat to unite over: Soviet Russia. As Colonel Edward M. House explained in his book, What Really Happened at Paris, published by Scribners as Scott and House set sail on the R.M.S Aquitania in May, the allies were seeking the Vatican’s cooperation on the issue of Lenin’s influence in Poland. The commissioners had found that there was “practically no Bolshevism among the Catholic population” which was “overwhelmingly in the majority”. The Poles were ardent Catholics, and that in itself was viewed as a “strong safeguard” against the spread of Bolshevism. [29] According to the press of the time, the meeting had been requested by Rome who had been concerned at President Wilson’s rejection of Benedict’s peace proposals some months before. [30] After months of negotiations it was finally announced that the Pope would not be granted a seat at the table in Paris, despite all the best efforts of Fay and his Peace Conference replacement, Father Paschal Robinson, to ensure it. [31] Within days of Harding’s arrival in the White House, the ‘Catholic infiltrator’ Joseph P. Tumulty was removed from his role as adviser.

Scott’s reaction to the death of Father Fay had been full of the usual histrionics. In a letter to Shane Leslie dated January 13, 1919 the author made little or no effort to conceal his desolation: “Dear Mr Leslie, I can’t tell you how I feel about Monsignor Fay’s death—he was the best friend I had in the world … Oh God, I can’t write.” A short time later, Scott would compose another letter, significantly ramping up the ante on his grief: “Dear Mr Leslie, Your letter seemed to start a whole new flow of sorrow in me. I’ve never wanted so much to die in my life.” [32] In later years, Shane would write that Fay’s last thoughts must have been with Scott. He also related a supernatural experience, said to be too “ghastly” for words, in which Fay had made himself present in spirit form at the foot of Scott’s bed. [33] In his debut novel, This Side of Paradise, Scott would lay the blame for the priest’s early death on the burdens placed upon him by former British Ambassador Cecil Spring-Rice — a distant cousin to Leslie — and Henry Adams, an adviser to President Wilson, whose father, Charles F. Adams, had played a pivotal role in keeping Britain neutral during the American Civil War. The way that Scott saw it, Fay had been “leaned on”. The author believed that Adams and his friends had too often taken advantage of the ‘amazing radiance’ that Fay exuded and which he had brought to the dark, shadowy corners of world affairs. [34] And in all fairness, he probably wasn’t too far off the truth. It was Ambassador Spring-Rice, described as one of Leslie and Fay’s “most intimate friends and collaborators” who had sought to embed both men deep into the pro-war matrix in Washington as intermediaries between the British Foreign Office and the American Catholic hierarchy. The British Foreign Office and US State Department had demanded solutions and reconciliations, and Fay had supplied them generously. [35] In his memoirs, Shane Leslie would recall an incident in which Fay had literally thumped his fist on the table in an attempt to impress his message on the Pope. According to Leslie, Fay’s frankness had pleased the Pontiff who was “able to judge the future better and to discount previous informants”. In another diary entry Shane added that the British Foreign Office thought Fay more effective than the President’s official adviser, Colonel Edward M. House, one of the five American officers assigned to the Peace Conference in Paris who had travelled with Scott to England on the RMS Aquitania in May. [36] Writing of Fay’s creative contributions to the war effort in Rome, Leslie would confide in later writings that it was the belief of the Foreign Office that “had Fay survived the war, many subsequent troubles would have been immensely lightened”. [37]

For a short time after his death, Scott had wanted to be like his old friend: he wanted to be “necessary to people”. And not just “necessary”, “but indispensable”. He wanted to be able to offer the same “amazing bursts of radiance.” [38] Leslie suggested that Scott should anchor himself in the priesthood, and not rush headlong into Bohemia as his passionate romance with Zelda seemed to be making inevitable. Rome was the only “permanent patria” to which all of them could belong. [39] Scott made no further mention in his letters of their aborted trip to Russia and the burdens that both men would have faced, and which he had been more than prepared to bear back in August 1917. And that time, Scott seemed perfectly comfortable to accept the challenge, and Fay was literally bubbling over with excitement about the mission, looking forward to the day when they would go to New York and get fitted for uniforms:

“In the eyes of the world, we are a Red Cross Commission sent out to report on the work of the Red Cross… and that is all I can say. But I will tell you this, the State Department is writing to our ambassador in Russia and Japan, the British Foreign Office is writing to their ambassador in Japan and Russia, and I have other letters to our ambassador in Japan and Russia, and to everybody else in fact who can be of the slightest assistance to us … To my mind the most extraordinary thing about it is that we may play a part in the restoration of Russia to Catholic unity.” [40]

If Fay had been buckling under the strain of his duties, then it certainly wasn’t obvious to those who knew him.

Leslie responded to Scott’s accusations in his review of the novel in the Dublin Review in October 1920: if Adams (‘Thornton Hancock’ in the book) had leaned on Fay then it was only because Cecil Spring was leaning on Adams. [41] The weight placed on Leslie’s shoulders had very nearly led to his own nervous breakdown. The pressures on everyone had been immense. Cecil Spring had died in February 1918 and Henry Adams had survived him by only a matter of weeks. Pulling the odd ‘rusty wire’ and suffering for the cause was par for the course. According to Leslie, it was Fay who had floated the idea very early on in the war of making the Nationalist moderate, John Redmond Premier in Ireland, “with an Irish Brigade in the French Army, and then using a pacified Irish-America to prop up Wilson’s wobbly war policy”. Fay’s efforts on behalf of Washington had been challenging to say the least. Leslie revealed that after arriving in Rome as a courier of secret messages from the White House, under the disguise of a Red Cross officer, Fay had been followed to the Vatican “by the Secret Service of three nations.” [42] In Leslie’s opinion, it was Father Fay’s own dogged determination to get things done and deals agreed that had led to his early death. He’d been floored, and eventually buried, by his own relentless enthusiasm, his “will to believe”. The covenant of The League of Nations may have been the “cruel engine of oppression” for the Harding administration, but for Fay it would be his lasting, if not entirely expected, legacy. Speaking to the League of Political Education just weeks before his death, Fay, now serving as the Pope’s domestic prelate, had put his case before America: as head of the Catholic Church it was essential that the Pope should have a voice in guaranteeing a permanent peace. Having a formal representative at the talks would ensure the delivery of all three main points of the League: the formation of a formal assembly, the disarmament of the nations and an international court of appeals. Not everything he said that day had the expressed approval of Rome. In fact some of statements he made had not only been unauthorized, they had also been deeply provocative, sharing as he did the details of a private conversation, in which they Pope was reported to have said that he had not been “neutral” during the war. “I am not neutral,”, Fay said quoting him, “No one can remain neutral where morality is involved, but I have tried to be impartial.” Fay concluded his address by making some vague allusions to a permanent place for the Pope on the League’s official council. Even those who backed the League in principle were left shocked at the far-reaching consequences of such a ‘presidency’. [43] Fay was acting like a man possessed. His vision of everlasting world peace, with a Catholic pontiff sitting as President of the League, was extraordinary stuff — even by Wilson’s standards. Most Americans viewed the whole thing with no small amount of caution. More importantly, how were the British, and the Archbishop of Canterbury going to react? Even Fay’s old friend Henry Adams had remained sceptical about the League right up to his death. What he had been seduced by was Fay’s boundless idealism and his “extraordinary gift for hope” in restoring order out of chaos, principally through God. Wilson’s mad dash trip to Britain in December 1918 and his steaming across to Rome in January weren’t the result of some cosy state visits, they were made out of desperation. It wasn’t by chance that the Archbishop of Canterbury was at the Embassy in London with former Ambassador Bryce that day. [44] In the heat of the moment, and literally trembling with his own beatific vision, Fay had unwittingly started the wildest of fires, leaving Monsignor Cerretti, who was about to set sail to America as Papal Secretary of Extraordinary Affairs, with the most intricate of battles to fight. At the last moment, Cerretti was ordered to remain in Paris. It had already been determined that Wilson would be coming to them. [45]

The irony, of course, is that in the end it would be down to people like Scott, Beach, Pound, Hemingway and the Murphys — and whole coterie of colourful American ex-pats — who would truly begin to realise the hopes and ideals of the old Entente Cordiale. Never before would the swelling colony of American Bohemians in Paris prove so useful to the Church and State, promising as they did, an emotional and intellectual bond with Europe that until now had never been thought possible. It would be men and women like these who would expose the American consciousness to the broad umbrella of internationalism. If there as to be any ‘special relationship’ it had to start with the natural absorption of an off-kilter American psyche into the more traditional membranes of ‘Old World’ Europe. It was in all fairness, the unlikeliest of marriages — but somehow it worked.

The 4th July, 1921

Given the considerable time and energy that British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George had poured into the League project, the news of Colonel George Harvey’s appointment and Harding’s pledge to take no part in the creation of a “world super-government” was everything that Britain hadn’t wanted to hear. For Britain the project had always been economically motivated. Britian didn’t want to destroy Germany, it wanted to trade with it. Just as wished to trade with America. It was idealists like Wilson who viewed it as part of the fulfilment of some cosmic law. During the previous five-months, Britain had done everything in its power to reaffirm this ‘special relationship’. Winston Churchill, who many Americans had regarded as “⅞ American” and only “⅛ Blenheim”, had got the ball rolling with a stellar address at an English Speaking Union meeting at the Hyde Park Hotel in February that year. He knew damn well what was coming: “we must exert every influence at our disposal to make sure that the government and people on either side of this ocean understood each other’s point of view and endeavoured to harmonize their own policies as far as they could.” [46] The League of Nations was not the only bone of contention.

President Harding had also been hardening his stance on China and Japan: the “Yellow Peril” — something backed in full by Lothrop Stoddard. In January that year, The Times of London had published the article, West Versus East by American-Irish author, S.S McClure prophesising a catastrophic outcome to the escalating naval rivalries between the Britain, the US and Japan. [47] McClure predicted that the next war would be waged on a huge scale, not between nation and nation but between East and West. Six years later, Scott would repeat this same mantra in an interview with Harry Salpeter of the New York World: “The idea that we’re the greatest people in the world because we have the most money in the world is ridiculous. Wait until this wave of prosperity is over! Wait ten or fifteen years! Wait until the next war on the Pacific, or against some European combination!”. Over drinks in the tea-garden of the Hotel Plaza in New York, Scott revealed how over the next fifteen years the world would begin to see how much resistance there was to ‘the American Race’, and that it would take a war to prove it. He wasn’t proud to be American, and claimed never to have said he was American. Only in wartime was it possible to say one was American like a Frenchman could say they were a Frenchman. America’s meaning and identity would evolve only from conflict. [48] Scott had arrived at the concept of Différance some forty years before Derrida, even if it was a little slurred.

McClure and Harding saw it in the simplest and starkest of terms: China and Japan were determined to seize territory across on the other side of the Pacific. Not only this, they would also seek to inspire the peoples of Africa and Asia to overthrow imperial rule. He saw a race war to end all race wars. [49] There was only one problem: Britain’s much coveted Anglo-Japanese Agreement, signed in response to a shared threat from Imperial Russia in 1902, was about to expire. If Britain and Japan were to renew that treaty, things could take a turn for the worse. Winston Churchill, speaking at a cabinet meeting on May 30 didn’t even attempt to disguise his fears: it would be a “ghastly state of affairs” indeed, if Britain were to drift into “direct naval rivalry with the United States.” Right now there would be dozens of United States Naval Officers talking to the White House advising that the renewal of the agreement should be taken as indication that Japan was Britain’s ally. [50]

At the end of June, Scott and Zelda returned from their disastrous stay in Rome. Among the masses of heaving bodies at an utterly sweltering Hotel Cecil were delegates of the annual Imperial Conference. This year, the conference had been organised to address the new problems facing Britain: rapprochement with Harding’s America and reaffirming its alliance with America’s new enemy, Japan. An essay written by author and former Government propaganda man, Francis Gribble and published in the Sunday Mirror at the time of the Imperial Conference sketched out the rubric of the challenges they now faced: “what one needs to realise in trying to get to the truth about American sentiment is that America, unlike England, is a political rather than a racial unit, and is therefore less likely to feeling and thinking as one man.” The essay’s title couldn’t have made it any plainer: ‘Do Americans Really Like Us? Bonds of Sympathy Must be Preserved’. Attempting to elucidate on America’s problem, Gribble described Lothrop Stoddard’s response to Israel Zangwill’s shamelessly idealistic ‘Melting Pot’ idea: strictly speaking there were no 100% Americans. The ‘Melting Pot’ was a crucible which if it did melt the ingredients, certainly did not fuse them. [51] The article had been written in response to the chaos that had ensued when America’s British-born Naval Commander, Admiral William Sims had made a rather frank admission at a meeting of the English Speaking Union in the first week of June. In Sim’s estimation there were too many Americans — many of them holding influential positions in office — who did not like the English. He didn’t name Harvey directly, but there’s no doubt about who he meant. His succouring up to the Irish had been appalling. It was the Admiral’s belief that Sinn Féin sympathizers in the US had been out to destroy the nation and had both English and American blood on their hands. Worse still “false news” sought to destroy the bonds of sympathy and cooperation that the two were now trying desperately hard to preserve. [52] Sims had arrived on in London just one week after Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald had sailed into England on the Aquitania with the new US Ambassador, Colonel George Harvey on May 10th. [53] The Admiral and Ambassador were dragged immediately into an ugly diplomatic spat and attempts were made by Illinois Senator, Medill McCormick to have Sims recalled to Washington. The Admiral eventually headed back to the United States in the last week of June. The spat was the second crisis the new Ambassador had had to resolve. The first had happened on the eve of Harvey’s departure to England when President Harding announced that after much speculation they would not be setting up an embassy at the Vatican in Rome. After a frank discussion with longtime Vatican delegate, Monsignor Bonzano, a decision had been made. Bonzano had predicted violent reactions from White American Protestants, but he also had huge reservations about the President himself who had expressed no small amount of prejudice on the ‘Roman Question’ over the years. A short time later it was announced that formal diplomatic relations were definitely not on the cards. [54] Diplomacy instead, would be focused on Mussolini’s whose bid for power in Italy which was dependent on Wall Street investment, and whose championing of Fascism would be welcome in the fight against Bolshevism and organized crime. [55]

As a result of their disappointing adventures in France and Italy, Scott and Zelda had missed much of the controversy, arriving back in London on June 30th , just as the Lloyd George and the members of the Imperial Conference were completing the formalities and introductions and getting down to the serious business of resolving problems between America and Japan in the Pacific. [56] Trouble was also brewing at the Cecil among the Arab delegation from Palestine led by Musa Kazim Pasha who were thrashing out the terms of the Brit-led Jewish Mandate. Little wonder that the couple took the opportunity of dining away from the Hotel Cecil at Claridges, where Scott would later recall being served strawberries in a gold dish by an ‘inattentive’ waiter in the greyest of surroundings. [57] Lady Helena Squires, the wife of Sir Richard Squires, the Prime Minister of Newfoundland, would arrive there too that week.

As they arrived there was bad news for their friend Shane Leslie. On June 29th, Shane’s aunt, Lady Randolph Churchill — the American-born mother of Winston Churchill — had died from complications sustained in an injury whilst staying at Melles Manor in Somerset. [58] The couple had encountered the legendary ‘Jennie Jerome’ shortly after their arrival in London back in May and it was grim irony indeed that she should pass so soon before they left back for the States. Shortly before his death in 1940, Scott would recall their trip to Jennie’s house in Sussex Square in a letter to Zelda: “Do you remember luncheon at [Winston’s] mother’s house in 1920 and Churchill who was so hard to talk to at first and turned out to be so pleasant?” Scott had just that week received a copy of Churchill’s book, The Life of Marlborough and looked forward to reading it in bed the following day. [59] In another letter, Zelda would recall how Lady Randolph had served them “strawberries as big as tomatoes.”

As the couple enjoyed their last few days soaking up the “long majestuous twilights” reflecting on the River Thames, plans were being made for Independence Day celebrations. At the Hotel Cecil on the evening of July 4th, the newly arrived American Ambassador, Colonel George Harvey addressed the American Society in London at a banquet held to celebrate the ‘Glorious Fourth’. As the guests polished off their lavish gala dinner the Ambassador talked optimistically of an Anglo-US-Japanese pact being agreed and hopes for a deal in Ireland. [60] When America made its declaration of independence some 145 years previously, the white population of the entire thirteen colonies had been just three million and practically every one of those people was English. Harvey thought it was strange indeed to think that thirds of all the English speaking people of the world were now living under the Stars and Stripes. Respecting that fact, Harvey said that he had no desire to either “twist the lion’s tail or make the eagle scream.” America was indeed a Land of Milk and Honey, where many of its people were rich beyond the “traditional dreams of avarice”, much of it accrued, some cynically suspected, as a result of the Great War. Even if it that were true, Harvey concluded, then any gains the country had made during the war had been adequately recompensed by the European relief efforts rolled out by Wilson and Hoover. [61] Harvey stood before the dinner’s organiser, the oilman Wilson Cross and its speaker, Arthur Lee, Lord of the British Admiralty, and made light of the inauspicious start of this special relationship with a slightly awkward wisecrack: the Fourth of July bells they had heard ringing at the start of the evening were unlikely to have rung that sweetly if George V had been anything like George III. [62]

The 4th July, 1919

Scott had probably quite rightly spent the first half of the day in Cambridge and Grantchester, visiting the rich constellation of university colleges that dominated the town, most likely with his host, Shane Leslie, in tow and a well-thumbed book of verse by Rupert Brooke in his pocket. The following year Leslie would publish The Oppidan, telling a fictionalized account of his experiences at Kings and which Scott would review for the New York Herald Tribune in May. Scott had started his review by saying that there was in Leslie a “stronger sense of Old England” than any other person alive. The man who had sat at the feet of Tolstoy and gone swimming with Rupert Brooke, and whose books possessed the “low haunting melancholy of a great age”, was weaving his magnificent quilt against the “shadowed tapestries of the past.” [63] The past for Leslie stuck to the heels of his feet like gum, and he left traces of it everywhere he placed his feet. The past wasn’t just a burden, it was a sticky and obstinate promise that wouldn’t let go to matter how hard you tried to break. In another column on the page, Burton Rascoe, the Tribune’s literary editor, shared an anecdote about the publisher, Otto Liveright, who he had lunched with the previous day. Liveright had been disturbed by Rascoe’s irreverent attitude toward Freudian analysis. The editor had thought it a good thing generally, but was of the opinion that ideas about mind, habit and personality had already been expounded years ago by Plato, Plotinus and the early Churchmen. The therapeutic value of psycho-analysis had, Rascoe suggested, arisen from one of the “oldest and greatest institutions of the Catholic Church — the confessional”. One was rid of the burden of sin when one confessed it. On the Fourth of July two years earlier, Britain’s new Secretary of War, Winston Churchill, Colonel House and US Ambassador Davies had addressed members of the same American Society at the Savoy Hotel, reiterating the responsibility that Britain and America bore in smashing the Bolshevik threat. Perhaps the ‘white man’s burden’ that Churchill almost certainly alluded to again that day, was a sin shared by the two countries, and one that could only be absolved by the smashing of some imaginary primordial threat.

Scott took on big responsibilities himself that year too, because it was on the Fourth of July 1919, that the author had left his $90 a month job at the ad agency in New York and headed home to Saint Paul, where for the next 12 months he would take up occupancy in his old room on the third floor of parent’s house on Summit Avenue and complete his first novel. In an article written for the Saturday Evening Post the following year, he had described feeling “utterly disgusted” with himself and those around him. Splitting his time between his day job writing snappy promotional jingles and evenings working on stories had left him feeling restless. We keep you clean in Muscatine”. That particular jingle for the Muscatine Steam Laundry company in Iowa had earned him a raise. Pretty soon the office wouldn’t be big enough to hold him, he boasted. But within weeks the boredom had set in and not for the first or the last time in his life was Scott feeling like a “cracked plate”. The poet-prophet was quite emphatically wasting his talents. He was neither one place nor the other, marooned somewhere between the gutter and stars.

Occasionally a letter from Zelda in Alabama would arrive and raise his spirits, but the happiness would be short-lived and even the fears about that would return. As besotted as she was with Scott, Zelda had refused to set a date for the marriage. A ring had been bought, a ring had been received, but after months, there was still no talk of setting a date. To make matters worse he wasn’t sleeping. He’d wake up at 3.00am and for the rest of the day the clock would be frozen at three, the minutes and hours only a dangerously thin lengthening of that one last hour. Everything that came after that time was rambling, elongated and disjointed. In the apartment below, the 47 year old composer Julius E. Andino would be banging away at the keys on his ragtime piano, perfecting some arrangement for bosses at the Knickerbocker Harmony Studios on Broadway. On occasions like these Scott would find himself hovering like a ghost outside the Plaza Red Rooms; anywhere that would take him away from his drab apartment at Claremont Avenue, his “shabby suits”, his “poverty”. Many years later Scott would write that “one by one” his “dreams of New York were becoming tainted.” When he had arrived the city had had “all the iridescence of the beginning of the world.” The dream of the city was the one thing that had kept him going. But things had soured. Scott had allowed himself to place his “inadequate bark in the midstream.” [64] Occasionally he would find himself drifting away from his room on the corner of 127th Street, but every time he got as far as the subway he would break into a “tireless, anxious run” that would bring him right back home. Living there had allowed the raw light of reality to penetrate its fragile skin and like his future creation Jay Gatsby, the world he had found there was somehow lacking — it was new and unfamiliar world, a world that whilst material enough, wasn’t real exactly. A process of self-disintegration was setting in. [65] On the night of the 3rd he had got “roaring weeping drunk” and he headed back to the subway.

With his last few dollars Scott had hopped into one of the train cars of the Chicago, Milwaukee & Saint Paul Pacific railroad and headed back to Summit Avenue, a street which just a short time later he would describe as a “house below the average, on a street above the average.” [66] Fitzgerald’s first biographer Arthur Mizener would describe the house as located in an area where the avenue declined into a “socially undistinguished street”. Like so many other times in his life, Scott had found himself hovering on a boundary that was somewhere between mediocrity and greatness. A little farther up the street was the 36,000-square-foot Gilded Age mansion of ‘the great’ James J. Hill, the Canadian-American empire builder whose influence on the town had been the stuff of local legend. Hill’s name would be immortalised in Scott’s 1925 novel, The Great Gatsby, when Gatsby’s father, Henry C. Gatz,remarks that had his son lived “he could have been a great man, a man like James J. Hill.” [67] Scott’s mother Mollie McQuillan and his aunt Annabel had been good friends of Hill and his wife Mary, the three of them having given generously to the building of St Mary’s Church in Lowertown. For many years there was a large white marble font that had been kindly donated by Scott’s aunt, Annabel McQuillan, the first person ever to have been baptised in the church. A report in the Saint Paul Daily Globe from September 1888 reveals that Scott’s aunt Annabel McQuillan had been maid of honour at the marriage of Samuel Hill and Miss Mary Hill. In 1925 members of the Hill family would bequeath his enormous house to the Catholic Archbishop, Austin Dowling, who was at that time residing at a far more modest property at 299 Summit Avenue. [68]

Scott had left New York on the hottest Fourth of July on record. At 8.00 am in the morning, the temperature and had been a sweaty and oppressive 77 °F. By the afternoon of the Fourth it was nudging 100. Scores of New Yorkers had taken advantage of the national holiday by swarming to the country and the beaches, with the bays at Coney Island and Brighton getting particularly swamped with bodies. It was the strangest Fourth of July that many Americans had ever experienced. On July 1st, the Wartime Prohibition Act had come into effect, providing a stop-gap of sorts to the constitutional Volstead Act that came into effect the following year. On the day that America would come to know as the ‘Thirsty First’, the nation went dry. 125,000 saloon doors closed, 1,247 breweries closed and were 645 distilleries were abandoned by workers. Until then Uncle Sam had been the biggest consumer of liquor. There was some consolation. As news of the act spread throughout the States there was talk of Wilson lifting the ban as early as August, when the whole demobilisation process would be complete. There was also talk that Wilson had tried to win exemptions for beers and wines, but this was quickly dismissed as ‘brewery propaganda’. Those cocky enough to violate the ban would face fines of $100 and $500, and even jail terms for multiple offences. Overnight a staggering 70, 000, 000 gallons of whisky were consigned to storage, and by July 2, Minnesota and New York were bone dry. Some States towns didn’t even bother celebrating that year, the wartime ban on fireworks and a grim, continuous barrage of warnings from National Security dampened what were already weary spirits. On the day that America celebrated its independence the papers were asking Americans to ‘Prepare Against Bomb Plots’. On May Day that year, a parade between the Bronx and Central Harlem had been broken up by Police when crowds had charged at ‘Bolsheviki’ Red Hats waving ‘Free Your Fellow Workers’ signs. Just a few days later Scott would wander down to the Plaza Theatre on 58th Street to see what was showing and find Louis J. Selznick’s propaganda film Bolshevism on Trial being shownon constant rotation with Douglas Fairbank’s war bonds movie, The Knickerbocker Buckaroo, a movie which had been specially commissioned by the US Treasury Secretary, William McAdoo and his assistant, Oscar Price. Fairbanks and Marjorie Daw would provide the eye-candy whilst McAadoo’s friend — and Scott’s boss — Barron Gift Collier would spearhead the state-wide advertising campaign that accompanied the movie and the fifth and final bond issue rolled out that spring — some of which were purchased by Scott after the success of his first novel. [69] Collier’s impact on sales of the loans was even more dramatic than Fairbank’s movie. As a result of the ad agency’s generous and patriotically-driven street car advertising campaign more than 50,000,000 Americans were being reached every 24 hours across 4,000 cities. [70] Scott was living through a divisive and polarized time. Not for the last in its history, Americans were being served a clear ultimatum: you were either with us, or against us — and if you were with us, then you were being asked to dig deep in your pockets to prove it.

The author would write about the skirmishes the following year in May Day. Fears were so bad that some States were demanding the deployment of federal troops to ensure that the Fourth of July activities passed by without incident. In New York on the 3rd every man in the New York’s Police Department, 11,000 in total, had been mobilized and were told to remain on duty until the celebrations had formally ended on the 5th. Special guards had been thrown about the city’s public buildings and the homes of its prominent citizens on Fifth Avenue. Despite the White House insisting that it had no specific intelligence on any alleged plot, the New York Guard, reinforced by Secret Service agents were ready to respond with the rumoured ‘Red Bomb Plot’. In defiance of the non-existent threat, the National Security League organized a series of lesser pageants and patriotic meetings around the city. In the most extreme cases the leaders of the celebrations were warning that unless Americans increased their vigilance, this Fourth of July may well be the country’s last. [71]

On June 12 Police had raided the offices of Soviet-sympathizer Ludwig Martens at 110 West 40th Street. Being just a few minutes’ walk around the corner, Scott would have heard the sirens wail from his office in the Candler Building. The man leading the raid was Special Agent Harry Grunewald who just two years before had grilled Scott’s speakeasy friend, Max Gerlach about his alleged ‘activities’ in Germany. According to the New York Tribune, the raid had been a total surprise and Grunewald and his men had been able to seize a substantial of amount of data from the so-called ‘Red Ambassador’. [72] It was in the atmosphere of widespread panic and disillusionment that Scott packed up his things and went home. The job in New York was meant to have opened the doors of opportunity but everywhere he went he found them being slammed shut — even the door of the local bar. Scott had arrived at Penn Station around 4.00 pm — the hottest part of the day and for many, the hour of madness. In his head he was still carrying ‘confidential war papers for President Wilson’, a bluff he had occasionally used to get him back to his unit from New York during the war. [73] In his head, he was doing something that had far-reaching consequences, not just for himself but for his country.

As Scott waited for his connection to Union Street Station in Chicago, the two blocks around Eighth Street would have dotted by patrol men marking the gutters down which the hordes of festival goers would rattle after the celebrations had ended at 5.00. Scott was making it out of the city just in time. Just a few minutes earlier, a group of howling teens, loaded on whatever cheap spirit they’d got their hands on had thrown a lighted firecracker into a packed surface car. The cracker had exploded and had burned the face of a boy quite badly. The climate at the station had already been aggravated by the inevitable delays that had resulted from the driver strikes on the local routes, the accumulations around Grand Central making it virtually unapproachable. The place was literally baking. To make it out of the city, Scott had to be creative, and took several connecting routes.

During the long hot journey home Scott had pulled out a copy of Hugh Walpole’s, Fortitude, a gothic fairytale reimagining of the author’s adventures as a young man in Cornwall, England. [74] Turning the book’s pages it soon became clear that is what the life of a young author was meant to be like: “It’s not the number of years you live that really matters. It’s what you put into those years that count,” says one of the book’s characters. The keynote of a man’s life had to be quality, not quantity. It wasn’t life that mattered but “the courage you brought to it”. [75] The ideal that Walpole was pushing was as old as the town of Saint Paul itself. Fortitude wasn’t just the key to a daring escape, Scott had torn through its pages as if the very paper on which it was printed provided fuel and inspiration for his famished soul. Scott was punching in new coordinates. As he watched the tracks disappear behind him round the bends, the author had noticed something rather profound. If you were stack the sleepers and the crossties on top of one another, it was possible to form a ladder to the stars. Climbing to a “secret place above the trees”, Scott pictured himself literally sucking on “the pap of life” and gulping down that “incomparable milk of wonder.” [76] What he embarked on next would be done freely, subject to no interest but his own. The black shadow hanging over him for the past few months had started to lift. From this moment on he would become a full-time writer. For “two hot months” he would write, revise, compile and “boil down” his debut novel. [77]

When he did eventually arrive home on the evening of July 4th, his parents Edward and Mollie Fitzgerald were already making merry down at the White Bear Yacht Club in Dellwood, some twenty miles of the city. Whilst most of the popular Fourth parades had taken place at Lake Phalen, the Fitzgeralds had opted to spend the duration of the holiday at the White Bear clubhouse. Here they had a held a dance in honour of Scott’s sister, the 18 year old, Anabel, who was turning eighteen just two weeks later. The following day another dance would be held at the club for Scott’s friend, Alida Bigelow. A train would drop off passengers from Saint Paul right outside the club, so if Scott had been travelling in from New York, he might have got off here. In 1922 Scott and Zelda would move their gear out to the yacht club and stay there for their summer, Scott trying his best to thrash out a plot for Gatsby in between the regular dinners and parties, and Zelda trying her best not to behave like the typical wife. The decision to head to the lake might have been spurred by the unusually high temperatures the town was enduring. On the morning of the Fourth, the town’s Pioneer Press were reporting that temperatures were likely to reach 87 degrees Fahrenheit by late afternoon. The breeze coming off the lake would have provided a modicum of relief, and as a severe case of whooping cough was spreading fast through Saint Paul, the relative remoteness of Dellwood would have spared them the obvious risks of the crowds. The Fourth of July always seemed to be marred by tragedies and this year was no exception. Casualties of the celebrations included seven year old Helen Smith who died after her dress was set on fire by fireworks and 60 year old woman was left fighting for her life after being stuck by a car as it roared through Forest and Jenks Street. The parents of Captain Alfred M. Swenson would also have some bad news that day, when it was learned that their son had been killed in another road accident in Paris on the eve of his return to Saint Paul. Peace agreement or not, death continued to pester the living. In glory or in failure, Scott Fitzgerald had made it home. [78]

For a man who is regarded by many as the ‘High Priest’ of the American Dream, the cultural significance of the day that Scott had chosen to make the journey is impossible to ignore. July 4, commonly known as Independence Day or the Glorious Fourth if depending on how patriotic you were, marked the day that the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776. Ever since that time, Americans have used the date to honour the unique values of the United States: a stiff rebuke to tyranny and oppression — whatever form it took, whether it was kicking the ass of an aggressive Imperial power like Britain or flicking the Vs to that toerag of a boss at work. If ever there was a day to celebrate the shackle-breaking triumph of self-determination it was this one. Like a child in the thrall of the New Year celebrations, the build-up to the day — the thought of the firecrackers and the noise of the parades — seems to have energized and bewitched the young author in the most unexpected and profoundest of ways. What better day to break with tradition or go rasping against the grain than July 4? Year in, year out, the most important day on the US calendar would be dutifully carried out with all the magic and luminosity of a Walt Disney production. As the fireworks exploded a bittersweet anthem would play and the walls of the magic kingdom would be bathed in gorgeous light. As Walt himself would later say: it was “a world of Americans, past and present, seen through the eyes of my imagination–a place of warmth and nostalgia, of illusion and color and delight.” There wasn’t a patriot in the country who didn’t see it as the birthday of freedom. The editor of one newspaper that year had written that the Fourth of July 1776 had seen the planting of the American idea whilst the Fourth of July 1919, had seen the first apples fall from its tree. The healing of the nation was at hand. Earnest newspaper columnists were almost drunk with post-war bonhomie. America was where the germ of a possibility in one’s mind could become a reality in one’s eyes. It was a place were you not only hoped to be free, but dared to be free. What it wasn’t, Scott had realised, was an eight hour shift in the office. Rattling off commercial slogans whose only intent was to sucker rather than satisfy the American dreamer was almost certainly not what the day was all about.

Not everyone was happy. In the New York Sun that year, the editor had printed an open letter from an unhappy patriot: after the signing of the peace treaty with England and France the week before, was there any point in celebrating the day anymore? Formerly the day had stood for something, reasoned the author, but now that the country’s independence had been “surrendered to European domination.” In his eyes at least, America was becoming a laughing stock. The editor responded by repeating an address made by President Wilson in 1915: “The passion of America is to be permitted to live to her own principle. The only thing that she profoundly resents or will ever profoundly resent is having her life and freedom interfered with.” [79] Scott, like many Americans that year, packed his suitcase and boarded the train, saving whatever was left of his freedom, both as an American and as an artist.

Back to Fourth

In 1919, the ‘Glorious Fourth’ had been a day of fireworks, but two years later it had been a day when only the smoke of spent goals and mishandled opportunities would cloud the author’s vision. Scott had spent the day of the Fourth on his pilgrimage to Cambridge and Grantchester, desperate to catch sight of the spirit of his long dead idol, Rupert Brooke. It wasn’t a day of fireworks that year, but of ghosts. Interestingly, the events of July 4, 1921 would find the most curious of parallels in a scene from his first novel, This Side of Paradise. In the chapter, Young Irony, Amory Blaine and Eleanor Savage are taking a walk. It’s September and the pair are talking about the best time of the year to fall in love. Christmas was okay, maybe even Halloween, but Easter and summer were, the couple agree, an emphatic no-no. “Summer has no day”, says Eleanor. What about “the Fourth of July?” Amory suggests “facetiously”. For Eleanor, summer was “only the unfulfilled promise of spring, a charlatan in place of the warm balmy nights I dream.” For Scott, summer only ever seemed to end in disappointment. The great opportunities the season offered were all hollow, all fake. The conversation then switches immediately to Rupert Brooke. Eleanor mentions that Amory looks a lot like the pictures of the forever young poet. The boy privately muses that he had been trying to play the part of Brooke the whole summer. His attitude towards life, towards Eleanor, towards himself had all been “reflexes of the dead Englishman’s literary moods.” Quoting Brooke’s poems Grantchester and Waikiki had been their own pitiful way of restoring the deep feeling that they had but was no longer there and the “dream” that had once seemed so close but which now seemed a world away. On the Fourth of July 1919, Brooke’s impact on his life had never seemed so intense, but by the Fourth of July 1921, Scott was beginning to find the colossal significance of Brooke’s influence on his dreams and his life was vanishing forever. In Grantchester he had reached the light at the end of the dock. The closer he got the more obvious it became that it wasn’t the starlight he’d once dreamed about but a distress flare. There wasn’t a place on earth that could live up to these kinds of expectations. Sitting the Old Vicarage of legend Scott had discovered that was exactly that — an old vicarage. And the Orchard Tea Room was too crowded with tourists to absorb any of the lyrical energies that might have been left here by Brooke. References to the Fourth of July would be made in several of his stories over the years, usually in the context of something vaguely ‘not happening’ or relating to some kind of anti-climax. In his 1930 story, Two Wrongs, Scott writes: “Two men sat in the Savoy Grill in London, waiting for the Fourth of July. It was already late in May.” [80] As every child who has ever experienced the thrill of their first Super Bowl or FA Cup Final, the build-up and ballyhoo was always so much more satisfying than the game itself. Whatever happened in the three hours or the 90s minutes was always shit by comparison.

In the end, Scott and Zelda’s attempt to find some relief from the burden of Harvey’s celebrations at the Hotel Cecil on July 4 proved to be prove no less disappointing. As they sipped champagne and observed the waltzers at the dance at The Savoy Hotel that night, the couple were left shaken and appalled when an unruly drunk came up and sat beside them with what were “two obviously Piccadilly ladies.” [81] It was a typical reaction from Scott in some respects. Beneath the witty jazz veneer, the quips and the quotes, was the soul of an overly sensitive prude fighting off one bubble-bursting blow from the devil after another. Scott had found himself in a bit of queer place: he was no longer satisfied by the glossy, misleading hype of the so-called ‘dream’ but didn’t have a strong enough stomach for the less romantic realities of life. The whole pretence of his career as celebrity author was becoming a burden, even if he didn’t really understand why. Celebrity was something he had always craved. He had ‘his girl’ and he had his deal. The way he felt made no kind of sense at all. But time is a funny thing and the longer you look at something you thought you knew, the more unfamiliar it can seem. Like most people at 25, the author was just beginning to realise that the most powerful things in life, the things that had most hold over you and consumed most of your waking thoughts weren’t the things you understand, but the things you didn’t understand.

On July 4th 1921 it was clear that America and Britain had arrived at a similar crossroads: should America preserve that ‘special relationship’ and move even closer to the British Empire or should it start thinking about an ‘amicable’ separation? George Harvey, the ‘Green Mountain Boy’ of Vermont was in London to reveal a subtle shift in the country’s axis. America, the ‘shining beacon of hope in the world’, was preparing to dazzle a little less generously than before. At his inaugural address in March, Harding had revealed an America that in the “clarified atmosphere” of the post-war period was demanding a change in national policy. ‘Internationality‘ had begun to ‘supersede nationality’. It was Harding’s belief that ‘materially and spiritually’ the success of the Republic had always been in the wisdom of the ‘inherited policy of non-involvement in World Affairs’. Woodrow Wilson’s lofty pursuit of lasting world peace with a League of Nations was viewed by many as the actions of a vain, delusional man whose obsessive quest for glory had been nothing short of madness. The President’s incorruptible dream was not only jeopardising the country’s independence, it was ‘destroying the soul’ of ‘this great Republic’. To the many Americans who clung on to the ideals of freedom and independence, nationality was not a pariah but a panacea — a vital force, a prayer, a guiding light. [82] After the extravagant ideals of the Wilson Administration, the White House under Harding would be inducing a cold, hard freeze that would wake them from their crippling ‘Potomac fever’. Wilson’s Narcissism was out. Harding’s Echoism was in. The headlines in American newspapers the day after his inauguration spelled it out: ‘No Alliance with Old World, Promises Harding.’ [83]

At a keynote address in Chicago in June 1916, Harding had left the audience in absolutely no doubt, right from the start, about his intentions in the years ahead: ‘American opportunity for American Genius, American Defense for American soil’. The ‘America First’ slogan he had been shouting for the past five years would set the conditions at home ‘for the highest human attainment’. In March 1920 Harding had addressed a meeting of the Winter Night Club held at the Antlers Hotel in Colorado Springs. America’s part in the Great War had been “primarily and patriotically” in defence of its national rights, something he had no trouble at all in getting behind. As far as Harding was concerned, “a nation which did not protect its citizens did not deserve to survive.” His address that night couldn’t have been better timed. After twelve years as a solid Democrat base, Colorado was taking the kind of swing to the right that would sweep Richard Nixon to victory almost half a century later. [84] Once he had the keys to the White House the changes he was anxious to make moved along at a rattling pace. Although the Alien Restriction Bill passed in spring 1921, didn’t impose the same numerical quotas or restrictions on naturalization as it did on migrants from south eastern Europe, it did mark a period in which the light of Lady Liberty was dimmed a little. For a time at least, America’s intuitive grasp of progress was being put on hold. The next two scandal-prone years would see Harding and his supporters demanding an extended drying-out period of reflection and isolation: Americanism would ‘start at home and radiate abroad’. It was like America was trading in the comforts and conveniences of the Melting Pot metropolis for the shivering polar exile of a Rocky Mountain winter. The solitude they would endure would either twist and damage ‘American Genius’ forever or transform their glorious dreams and ideals into ‘glad realities’. One ‘great storm’ had passed but America was preparing for another one moving in. [85]