A look at the respected Russian scholar, propagandist and multi-linguist, Harold Williams in the context of the first English translation of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in January 1920. This article explores the relationship between Williams, Sir Bernard Pares, the United Russia Societies Association and the Anglo-Russian Bureau during the 1915-1919 period.

Born to a Methodist family in New Zealand in 1876, and able to converse in over fifty languages, the handsome if slightly starchy Harold Williams had served as foreign editor and special correspondent for The Manchester Guardian, Morning Post, Morning Chronicle, London Daily Chronicle and The Times in St Petersburg before, during and after the 1905 and 1917 Revolutions. He was also a friend and colleague of Aylmer Maude, a fellow Russian scholar and the uncle of Protocols of the Elders of Zion translator, George Shanks. It was whilst Williams was serving as the newspaper’s special correspondent in Russia that the London Daily Chronicle published its infamous report revealing what were alleged to be the ‘true’ Jewish names of several Bolshevik leaders in November 1917.[1] The report, false and inaccurate in several respects, was duly picked up by ‘Chief Whip’ Freddie Guest, Chairman of the National War Aims Committee and republished in its Searchlight journal.[2] Interestingly, Williams encountered Vladimir Burtsev, expert witness at the Protocols Berne Trials, for the first time in autumn 1905, shortly before the first publication of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion by Sergei Nilus in December 1905. Although eager to print his rejection of Nilus’ work, Burtsev claims that he was persuaded by members of the Russian State and St Petersburg police not to expose it as a fake, on the pretence that it would draw unnecessary attention to a hoax that had clearly been designed with provocation in mind. [3] Williams’ significance within the anti-Propaganda campaigns of Churchill and the Committee of Russian Affairs shouldn’t be underestimated, with at least one historian, Charlotte Alston, describing Williams as Soviet Russia’s ‘Greatest Enemy’. [4]

It was an exceptional life by any standards, marked by episodes of quiet, reflective withdrawal and extraordinary, explosive intrigue, the latter set of affairs being no better illustrated than by an incident in September 1911, when Williams and his wife Ariadna Tyrkova were investigated on suspicion of military espionage in Russia. In copies of telegrams mailed by Williams to his newspaper editor, H.A. Gwynne, and unearthed by Williams’ biographer Charlotte Alston in 2004, he describes how the Tsarist Police, led by a pro-German officer by the name of Kurz, had launched a series of raids on the couple’s apartment following the death of Russian Premier, Pyotr Stolypin:

“Without having any orders to do so and despite protests, they searched the effects of my brother [Aubrey] and myself and finally carried off all our correspondence, manuscripts, notebooks and photographs. Special attention was paid to newspaper cuttings. The search lasted five hours. No explanation was given of the motives for this extraordinary proceeding. No arrests were made. The number of police present was sixteen.”

The return of his papers, which included an Officer’s account of Russia’s disastrous naval campaign at Tsushima in May 1905 [5], was eventually secured by a mixture of moral reasoning offered by his firend and fellow academic, Sir Bernard Pares and the political influence of Gwynne – the leading voice in support of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in Britain — whose protests to the British Foreign Office were duly advanced by the Russian Ambassador, Sir George Buchanan. [6] [7] Holding a series of urgent discussions with Russia’s Minister of the Interior, Aleksandr Makarov, Pares had pointed that expelling Britain’s most talented Russian Scholar would be the “sharpest rebuff” Britain could have in its attempts to promote the study of Russia in England. A short time later, all charges against Williams were dropped and he was allowed to travel freely in and out of Russia. [8]

On November 10th 1917, just days after the triumph of the Bolsheviks in the October Revolution, The Daily Chronicle published a report revealing the ‘real’ Jewish names of several top Bolshevik (‘Leninite’) leaders including Trotsky (Bronstein), Zinoviev (Apfelbaum) and Kamenev (Rosenfeldt). It may be reasonable to speculate that the man making these claims was Harold Williams, at this time serving as The Daily Chronicle’s special correspondent in St Petersburg where he was also carrying out semi-official work for the Ministry of Information and the British Russia Bureau (Intelligence/Propaganda unit) — a post he had volunteered to fulfil without receiving payment. Despite carrying out the role on a purely voluntary basis, by October 1917 Williams was acting Joint Director of the Bureau with Hugh Walpole, his extensive contacts within the extremist parties of Russia having greatly extended the reach and influence of the Britain’s Russian Ambassador, George Buchanan. [9] The claim made in the Daily Chronicle in November was repeated almost verbatim by Reality: Searchlight on Germany, the vanguard publication for Captain Freddie Guest and the British Government’s National War Aims Committee in a report published on November 17th 1917.[10] His regular series of ‘vivid dispatches’ from St Petersburg were also syndicated in the Daily Telegraph and the New York Times.

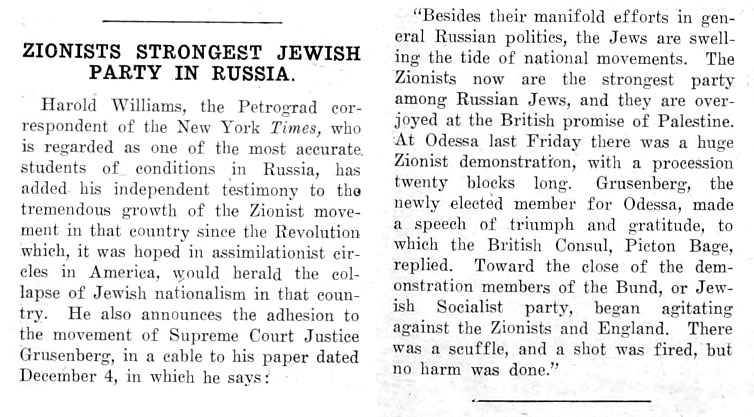

It was one of his despatches for The New York Times that Williams himself endorsing the view put forward by U.R.S.A’s Aratoon Malcolm and Colonel Mark Sykes Williams in which they were to formally recognize the potency of Russian Zionists in Britain’s ‘secret war’ with Lenin’s Bolsheviks. In a cable for the newspaper dated December 7th 1917 Williams writes: “Besides their manifold efforts in general Russian politics, the Jews are swelling the tide of the National Movements. The Zionists now are the strongest party among Russian Jews and they are overjoyed at the promise of Palestine.” [11] A later report from Williams in the spring of 1919 claimed that the Zionist Organisation of Russia had succeeded in enrolling over 600,000 adult Jews for the movement to establish a commonwealth in Palestine. Unlike in Europe and America, the Zionist ideal in Russia was reported to have “swept the Jewish masses … like a tidal wave”. In Moscow and St Petersburg well known Zionists were being arrested for promoting Jewish National interests rather than the International interests of Communism. [12]

Williams was not alone in his dedication to the anti-Bolshevik cause. His Russian wife, the Liberal politician, Ariadna Tyrkova (the first woman member of the Russian Duma) matched his passion and dedication blow for blow. The couple were long-time friends and supporters of Tolstoy and Christian Socialism, a movement that the young Methodist became increasingly frustrated by in the years leading up to the war, as he became more and more engaged with the Russian Liberalism of activist and economist, Petr Struve and the producers of the Osvobozhdenie newspaper. [13] It was through his earlier association with J.C. Kenworthy’s Tolstoyan colony at Purleigh in Essex that Williams was brought into contact with Aylmer Maude and Louise Maude Shanks, uncle and aunt of George Shanks. [14]

In 1916 Williams and Sir Bernard Pares, who would become lifelong friends and colleagues after meeting outside the Zemstvo Congress in Moscow in July 1905 [15], had been enlisted to work as part of an almost informal coalition of journalists and literary figures working in support of the British propaganda effort in St Petersburg. The Anglo-Russian Bureau, as it became known was intended to operate under the strict control of the British Foreign Office and the Ministry of Information; first under Charles Masterman and then John Buchan at Wellington House. Here the men specialised in writing articles for the Russian Press that would justify and explain the strength of the alliance to a war weary and sceptical public, both in Russia and at home. For the blustery young radicals of Britain’s union with Tsarist Russia had shown an extraordinary lack of ethics. By the summer of the 1916, newspapers like the Labour Leader, the official organ for Britain’s Independent Labour Party, had been developing a dangerous counter-narrative. In their estimation the Imperial Russian Government was at the present time “more reactionary than ever”. It was also keen to stress that and that “Prussianism at its worst” was nowhere as “tyrannical” as Russian and British militarism was today. Writing in early September 1916 the newspaper explained how the traditional prejudice against the Russian Government, “so fully justified by the history of her ruling class, is hard to kill” regardless of every effort that Britain was making to convince the public otherwise. The “new democratic spirit” said to have been inspiring the Russian government was nothing but a lie. According to the newspaper, the number of administrative exiles Russia was deporting to Siberia without trial was still running into the tens of thousands. The 120 people that the Tsar had proudly announced he had liberated were simply “a drop in the ocean”. [16] The Mass Amnesty demanded by the former Revolutionary Vladmir Burtsev at the outbreak of the war and endorsed by the Liberal Press of Russia had never materialised. [17] Even at that early stage the Labour Party of Britain had expressed them selves quite plainly on the subject of Britain’s alliance, the Scottish Socialist, William Crawford Anderson writing almost one year before to the day the Tsarist autocracy “was cruel, stupid and unchanging”. Choosing between Germany and Russia was like choosing “between the devil and the deep blue sea”. He had worse fears still; if the “tyrannous autocracy” had been “unbending in the hour of stress and difficulty”, what would be its attitude “in the hour of victory”? [18] Morgan Philips Price serving as correspondent for the Manchester Guardian was to express much the same sentiments at this time. In parliament, questions had opinions had already been expressed that Russia was tyrannical power who simply wanted to extend its Empire in Eastern Europe and “eat up Northern Persia”.

The man who oversaw the management and recruitment at the Bureau (also known as the International News Agency in Moscow) was the British Ambassador in St Petersburg, Sir George Buchanan with Hugh Walpole being brought in as Head of the group. Pares, who Williams had muscled-out of a role at the Manchester Guardian some ten-years before, would later describe his friend as the “greatest scholar whom we had ever sent to Russia”. [19] A year after being appointed ‘Reader in Modem Russian History’ at the University of Liverpool, Williams would become one of the founding members of the ‘School of Russian Studies alongside George Shank’s uncle and fellow Tolstoyan, Aylmer Maude. [20] Some ten years later Williams and Pares would collaborate again, this time on The New Europe journal, a weekly review of predominantly Slavic politics that Pares had launched with Robert Seton-Watson of The Times. The journal not only featured contributions and support from Harold Williams but also from news editor, Wickham Steed the man who had personally reviewed Shanks and Major Burdon’s The Jewish Peril for The Times of London in May 1920. Readers may also be surprised to learn that The New Europe journal was at this time being printed by Eyre and Spottiswoode — the very same printing company that Shanks and Burdon had used to print the first 30,000 copies of the English Protocols. It was around this same time that Wickham Steed offered Williams a position as a lead writer at The Times. Just two years later he was appointed the Director of its Foreign Department.[21]

In the post-Revolutionary period of 1918 Williams and Tyrkova were recruited into the pro-interventionist Committee on Russian Affairs, the Churchill-backed pressure group comprising of current and former staffers of British intelligence and the propaganda units in St Petersburg whose members, as we’ve already mentioned, included the writers John Buchan, Hugh Walpole, and the historian Sir Bernard Pares. In many ways this was a regrouping and redeployment, of the Anglo-Russian Bureau which been functioning just as casually in St Petersburg prior to the October Revolution.

In June 1918 Harold Williams had written to Protocols expert and anti-Bolshevik campaigner, Vladimir Burtsev saying it would be necessary for him to come to Britain. Writing in his 2017 book, Vladimir Burtsev and The Struggle for Free Russia, Dr Robert Henderson explains that on June 10th 1918 Williams had sent a telegram to Burtsev in Stockholm asking him to come back to Britain to take part in discussions and that he had succeeded in obtaining an entry-permit for him. [22] Immediately after this visit, Burtsev organised an operation base for his journal, Common Cause in Paris which was now at the centre of White Russian emigration (its production had been suspended for 12 months after his flight from St Petersburg in the aftermath of the October Revolution). [23] The journal was re-launched on September 17th 1918 and on the evidence of his discussions with Williams and other members of the former Bureau at least, possibly with British support and financial backing. By October 1920, just five months after the review of The Protocols in The Times, Burtsev’s journal had changed from being a weekly and fortnightly publication to a daily publication. [24]

In September 1919, just two months before George Shanks and Edward G.G. Burdon would publish The Protocols for the first time in English in Britain, Burtsev had been recalled to London by Sir Archibald Sinclair, the Personal Military Secretary to Secretary of State for War (and Air), Winston Churchill, and generally regarded as Churchill’s direct link to British Military Intelligence. According to letters unearthed by Dr Robert Henderson in the Churchill Archives Centre, Winston had got wind of Burtsev’s inspiring reports in support of Liberal Russia and was “most anxious to assist those Russians who wished to place their anti-Bolshevik viewpoints” in the strongest possible terms before the world. It is understood that Sinclair was looking for Burtsev, a talented publicist and respected voice, to ramp-up the propaganda effort on behalf of the White Russians and the Committee of Russian Affairs. [25] However, herein lay a problem. Burtsev, as we know, had been aware of the existence of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion since it was first published in Russia in December 1905. [26] What’s more, Burtsev had been assured by Russia’s Ministry of the Interior and Police at that time that not only was it a fake but that it had been designed with provocation and murder in mind. If U.R.S.A and the Committee of Russian Affairs had played a role in the production and translation of Shanks and Burdon’s Protocols, and if Burtsev had been so closely engaged in their work during this same period, then why did Burtsev not expose it as a fake until almost a year after the book’s English translation had received its sensational review in The Times — a newspaper that his friend Williams had such close links to? He had every opportunity of course. The Times report had caused a worldwide stir, and it’s terrifically unlikely that Burtsev, a voracious reader and barometer of public opinion on Bolshevism, would have been unaware of it. But this is something we’ll need to come back to.

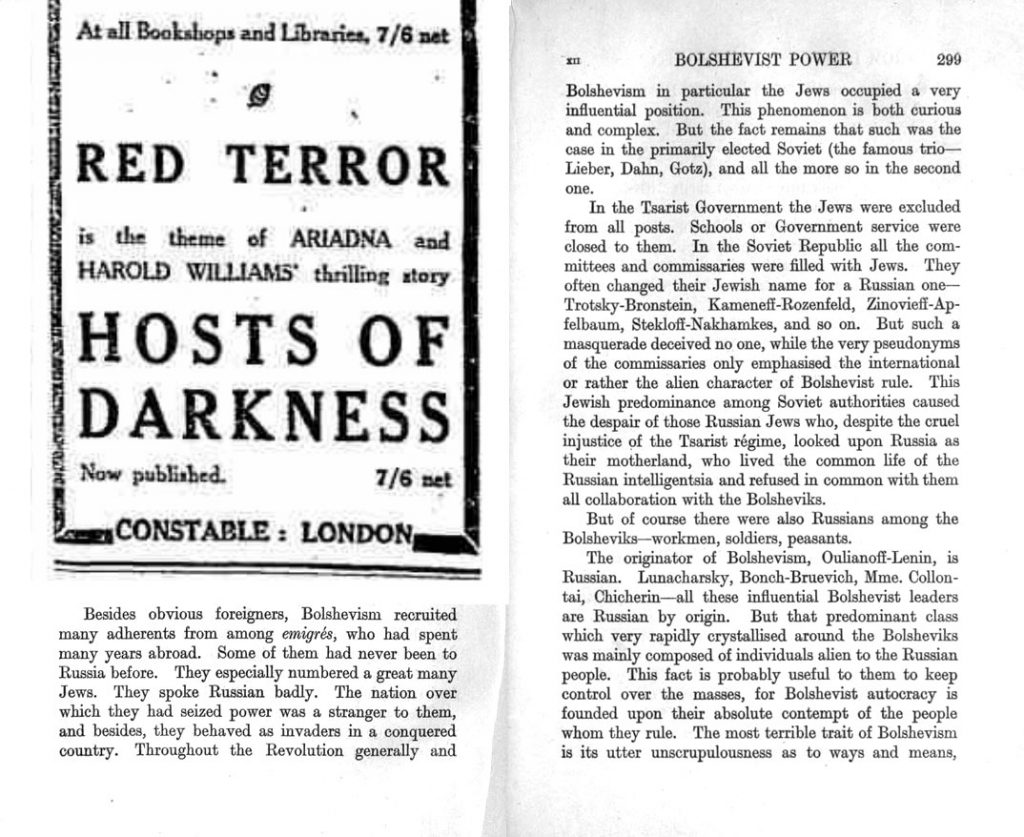

As strange as it may seem, the casual and slightly confused anti-Semitism that defined Churchill’s ‘Bolshevism versus Zionism’ article in February 1920 had its roots in ‘From Liberty to Brest-Litvosk’, a book written by Harold’s wife Ariadna Tyrkova-Williams. On one page she writes: “Besides obvious foreigners Bolshevism recruited many adherents from among the émigrés who had spent many years abroad. Many had never been to Russia before. They especially numbered a great many Jews. They spoke Russian badly … they behaved as invaders in a foreign country. Throughout the revolution generally and Bolshevism in particular the Jews occupied a very influential position. In the Tsarist Government the Jews were excluded from all posts. In the Soviet Republic all the committees and all the commissaries were filled with Jews.” [27] It’s probably fair to say that the Jewish-German-Bolshevik myth that began to take shape during this period was cultivated first by Russian Liberals like Ariadna Tyrkova-Williams, before being taken-up by British Liberals. From here it would take a sharp turn right where it would eventually find its place among the vitriolic narratives of The Britons and British Fascisti. Additionally, it may be possible to argue that the challenge faced by Tyrkova-Williams and other Russian Liberals had its roots in the 1905 Revolution and the demands made by some groups and individuals for Jewish self-determination and national representation within the First Duma. The issue of Nationality had been divisive even then. Much later, British and Irish fascists like Reverend Denis Fahey would quote Ariadna Tyrkova-Williams’ book during the fascist resurgence of the 1930s.

In 1922 Harold Williams and Ariadna Tyrkova-Williams published a novel called Hosts of Darkness. The novel used the same ‘Antichrist’ motif of Nilus’ original Protocols and which was again repeated by Churchill in 1920 article, ‘Zionism versus Bolshevism’. Williams was in fact, highly regarded by Churchill and remains a fascinating figure in Britain’s ‘scholarly’ war with the Bolsheviks.

Endnotes

[1] London Daily Chronicle, November 10 1917 (see: ‘A Boche Government’, Globe, Nov 10 1917, p.5). As previously mentioned, Harold Williams was a member of the Committee on Russian Affairs set-up by Pares and Buchanan.

[2] ‘Names of Leninite Leaders’, Reality: Searchlight on Germany, Issue 97, November 17th 1917, p.4

[3]‘The Elders of Sion: A Proved Forgery’, Vl. Burtsev, The Slavonic and East European Review , Jul., 1938, Vol. 17, No. 49, p.96

[4] Russia Greatest Enemy? Harold Williams and the Russian Revolutions , Charlottle Alston, Bloomsbury 2007

[5] Such an account brings to mind the anti-Tsarist activities of Elie de Cyon who was alleged to be using similar documents about the disastrous campaign in Turkey (again from a serving Russian officer) as a means of proving the incompetence of Alexander II as Russia’s leader.

[6] Russian Liberalism and British Journalism: The Life and Work of Harold (PhD Thesis), Charlotte Alston, School of Historical Studies, University of Newcastle-up on-Tyne, May 2004, pp.92-93.

[7] Arkadii Tyrkova, the brother of William’s wife, Ariadna Tyrkova was exiled to Siberia for his alleged involvement in The People’s Will (Narodnaya Volya), the group responsible for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. See: Women Journalists in the Russian Revolutions and Civil Wars: Case Studies of Ariadna Tyrkova-Williams and Larisa Reisner, 1917–1926, Katherine McElvanney, Queen Mary University of London, September 2018, p.60.

[8] A Wandering Student, the Story of a Purpose, Bernard Pares, Syracuse University Press, 1948, pp.181-183

[9] Russia’s Greatest Enemy? Harold Williams and the Russian Revolutions, Charlotte Alston, I.B. Tauris, 2007, p.108. Even if Williams has not written up the dispatch, it’s unlikely to have been published without his knowledge or his blessing.

[10] Reality: Searchlight on Germany, vol. 97, Nov 17 1917, p.4

[11] The Jewish Tribune, 21 December 1917 p.29/ ‘Jews Turn to Palestine, Russia in Throes of Huge Upheaval’, New York Times, December 7 1917 p.4

[12] ‘Zionists Make Splendid Propaganda in Russia’, Hebrew Standard, 9 May 1919, p.11

[13] Russian Liberalism and British Journalism: The Life and Work of Harold Williams (PhD Thesis), Charlotte Alston, School of Historical Studies, University of Newcastle-up on-Tyne, 2004, p.57

[14] Russia’s Greatest Enemy? Harold Williams and the Russian Revolutions, Charlotte Alston, I.B.Tauris, 2007. It will also be noted that like Aylmer and Louise Maude, Kenworthy was a key figure in the bid to provide passage from Russia to Canada for the Doukhobors.

[15] Russian Liberalism and British Journalism: the Life and Work of Harold Williams (1876-1928), Charlotte Alston, 2004, p.105

[16] ‘The New Russia’, Labour Leader, September 7 1916, No.36, Vol.13, p.1

[17] ‘Russia Our Ally; An Unchanging Tyranny’, Labour Leader, September 17 1915, p.5

[18] ‘Russia Our Ally; An Unchanging Tyranny’, Labour Leader, September 17 1915, p.5

[19] A Wandering Student, The Story of a Purpose, Bernard Pares, Syracuse University Press, 1948, p.122

[20] Russian Liberalism and British Journalism: the Life and Work of Harold Williams (1876-1928), Charlotte Alston, 2004, p.106

[21] Russian Liberalism and British Journalism: The Life and Work of Harold Williams (PhD Thesis), Charlotte Alston, School of Historical Studies, University of Newcastle-up on-Tyne, 2004, pp.222-224

[22] Vladimir Burtsev and the Struggle for a Free Russia, Robert Henderson, 2018, pp. 214-215

[23] Vladimir Burtsev and the Struggle for a Free Russia, Robert Henderson, 2018, p.220

[24] Vladimir Burtsev and the Struggle for a Free Russia, Robert Henderson, 2018, pp. 214-215

[25] Vladimir Burtsev and the Struggle for a Free Russia, Robert Henderson, 2018, p.220

[26] The Elders of Sion: A Proved Forgery’, Vl. Burtsev, The Slavonic and East European Review , Jul., 1938, Vol. 17, No. 49, p.96

[27] From Liberty to Brest-Litvosk: The First Year of the Russian Revolution, Ariadna Tyrkova Williams (Mrs Harold Williams), McMillan & Co Ltd, 1919, pp.298-299