One of the most frequently overlooked allies of Kinder Scout ‘right to roam’ campaigners, G.H.B Ward, William Rust and Benny Rothman was Herbert H. Elvin. Like Ward, Elvin had emerged in Britain’s blooming Trade Union movement, quickly recognising the positive trade-off between working men’s groups and sport. The Clarion Ramblers and Clarion Cyclists were among his earliest successes. Combining his role as General Secretary of the National Union of Clerks with his passion for physical and spiritual improvement saw him play a central role in the formation of the Workers Travel Association (1921). A letter signed by Elvin, described how a ‘cooperative effort’ was needed to make foreign travel as cheap as possible. The war meant that nations would need to rebuild and reconnect, not as enemies now but friends. Fascinating holidays and knowledge of continental people would help broaden Britain’s horizons and lead to a spirit of fellowship. There would be another positive outcome; properly organized travel would not only help heal a fractured post-war world, it would greatly increase the spread and resilience of International Socialism among its workers. His collaboration with Hulme-based pathways activist, Joseph Arnold Harrop and Fenner Brockway dated back to No Conscription Fellowship during the war. They would collaborate again in the 1920s with the launch of the Resist the War Committee when Elvin was drafted onto the group’s General Council. The work they did cleared the way for the Access to Mountains Bill, which was presented to parliament (for the umpteenth time) by the their mutual friend, Charles P. Trevelyan in 1927. In later years, Trevelyan would be nominated as President of the Society of Cultural Relations (with Russia), the British branch of Stalin’s VOKS.

The class politics that dominated the period between 1918 and 1926 had seen unprecedented militancy. Workers’ organisations had taken a sharp intake of breath and prepared for the imminent collapse of capitalism. The General Strike had represented something of a watershed moment. First the Unions had realised that large industrial action had the volume and the potency to influence government decisions, now it was the turn of sport. And it was from this same chamber of egalitarian high spirits that the British Workers Sports Federation would emerge, first with global competitions like the Workers Summer Olympiad in 1925, and then with more localised ‘shock and awe’ efforts like the Mass Trespass on Kinder Scout. The BWSF’s first Secretary was 55 year old Tom Groom, the original founder of the Clarion Cycle Club. His mantra remained constant throughout: through mutual aid and good fellowship ‘the Propaganda of the Principle of Socialism’ would remain strong. The future peace of the world could be secured in the ‘democratic arenas’ of International Sport. It was ‘footballs instead of cannonballs’. [1] The group’s formation, however, instinctively provided a lucrative opportunity to push International Communism. Within years of being formed, the well-meaning Groom was none too gracefully shouldered out. In his place were two emerging talents of the mighty Young Communist League — Wally Tapsell and George Sinfield. Under this famously obstinate pair, the BWSF would be re-calibrated under the banner and direction of the International Marxism.

The change couldn’t have been more profound or more successful. It put flesh on its bones and fire in its belly, trebling membership overnight. But solidarity was short-lived. To reap any real benefits at the polling booths, the aims, objectives and sympathies of the Sports Federation needed to remain close to those of the TUC and the newly formed National Labour. Even Lenin had acknowledged the value of an affiliation with Labour during the ‘Open Turn’ debate of the Second Congress of the Communist International. And the notion that was driving this way of thinking was ‘mass’. Labour was in a more capable position of revolutionizing the masses; the Reds could get in on the Labour ticket. As a result of an increasing misapplication of agitprop and a cruder, more truculent influence within the Manchester branch in particular, the mood amongst Labour members shifted from one of support of the BSWF to one of intransigence and in 1931, some months ahead of the General Election, Herbert H. Elvin and champion Clarion Cyclists, Ernest and John Deveney formed the National Workers Sports Association as an attempt to wrestle sport back into the more electable Labour mainstream. So far so straightforward. The Derbyshire-born Elvin, however, had a skeleton in his closet that betrayed his public switch to the more press-friendly National Labour.

“We ask that the wild moorlands of our country should be legally open to the walker … why indeed should not the waste places of Britain, the grouse moors and sheep runs be legally accessible to the thousands of men who merely want to see their changing moods, drink their grand air, and rejoice in their beauty.”

— Message from Charles P. Trevelyan read at Winnats Pass, ‘Rambling Freedom’, Manchester Guardian, October 3, 1927, p.3.

The Brotherhood

By the unlikeliest coincidence, the census of 1891 reveals that Elvin’s old family home at 77 Jubilee Street, in London’s East End was used by revolutionary fugitive Joseph Stalin during his attendance of the 5th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in London in 1907. Some thirty years later, ‘Stalin’s Englishman’ Guy Burgess, of the notorious Cambridge Five spy ring, found his way to the heart of the British Government as a Private Secretary in Ernest Bevin’s post-war Foreign Office. In September 1937 Elvin had replaced Bevin as President of the T.U.C but the Union men had remained close allies ever since lending their support to the founding of the National Travel Association in the early twenties and the formation of the Scientific Advisory Council in the thirties. Both men saw science as the key to progress in the fight against ‘Social Evils’. [2] Elvin’s youngest son Harold, who would eventually marry Indian actress, Tanguturi Suryakumari, would subsequently write of seeing Stalin at a four yard range with nothing between them. Harold, at that time serving as a member of staff at the British Embassy in Moscow, remarked that few pictures did Stalin justice: “Where do they show the sensitiveness? It is some water quality behind the pupils of the eyes. He looks like a too good father”. [3] The Sunday Post was quick to pick up on the author and film maker’s knack for being in the right place at the wrong time. “On a peaceful tour of Yugoslavia he was suddenly plunged into the turmoil which followed the assassination of King Alexander. When trouble started in Austria Mr Elvin was right on the spot and was thrown into prison for blowing up a railway bridge.” [4] Harold, who married Russian ballerina, Violetta Prokhorova on his exit from Moscow, was also at the Russian Embassy when Stalin learned of the surprise attack on the Soviet Union. Doubt still remains as to what his position was at the British Embassy. Contemporary accounts place him within the Ministry of Information, but from 1953 onwards, Harold was telling the press he really nothing more than a ‘lowly night watchman’. Whatever reason he had for being there, the dictator certainly took a shine to him as Stalin personally granted Elvin a rather exceptional exit visa for his new bride, Prokhorova. [5]

A closer look at the early life of Harold’s father Herbert H. Elvin reveals just as many mysteries.

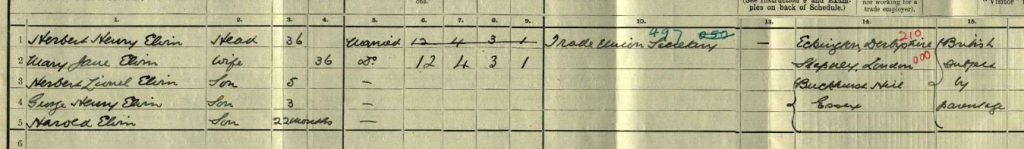

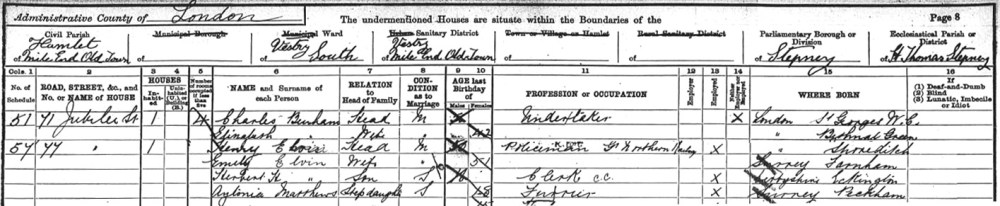

At little more than six months old, Elvin was scooped up in the arms of his mother and taken on a month-long passage to India. His father Henry Elvin was a Troop Sergeant Major in the 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers. The troopship Euphrates left Portsmouth on January 9th 1875 and arrived in Bombay on February 10th with over 1,400 men and women on board and some 145 children in tow. One woman and two children had died during the crossing and there is some indication that Elvin’s Derbyshire-born mother, Mary Ann Parr may have been one of those women not to survive. On the Unit’s arrival back in England in the mid-1880s, the family took up residence at 77 Jubilee Street. Within a few years of landing in Whitechapel, the young Elvin attached himself to the East End congregational movement and embarked on the rough and ready life of street preacher, slowly accustoming himself to the disrespectful mobs and the regular lobbing of horse shit and rotten eggs. From the age of fifteen Herbert would take to the labyrinth of courts and lanes around Dean and Dorset Street and drum up a crowd for impromptu prayer meetings, regularly being moved on for obstruction and unlawful assembly, and occasionally being prosecuted. Large gatherings in Hackney and Lambeth would usually degrade quite quickly into noisy, disorderly nuisances and thoroughfares would become congested. The vast mass of the lower stratum of East London life moved on a different plane, with most shunning the lasting salvation of communion wine for the short-lived comfort of a Ha’Penny gin. In the maze of incestuous alleyways and squalid courts of Stepney, the light at the end the world wasn’t the promise of divine grace but the ineffectual glow of the gas lamp revealing the sanctuary of the gutter where you would sleep. 1891 Census showing TUC President Herbert H. Elvin at 77 Jubilee Street, London with his Policeman father Henry. A young Joseph Stalin would lodge here in 1907. Direct engagement was the only credible solution.

Within a few years Elvin had married 24 year old Mary Jane Hill, the daughter of Congregational Minister, George J. Hill of Commercial Road in the Mile End district of Whitechapel. George had been leading the Seamen’s Chapel on George Street, subsequently re-named the Stepney Temple and it is almost certain that Elvin’s associates in East End Congregationalist movement brought him into contact with Reverend Arthur Baker of the Brotherhood Church on Southgate Road — scene of the 1917 ‘peace riot’.

As with most Congregationalist churches of the period, the politically charged, people-oriented Southgate Church mixed planned community ethics with copious measures of anarchism. Christian anarchism, fuelled partly by the commercial success of Tolstoy and partly by the emergence of Socialism, was based loosely on a statement made in the Book of Judges: “there was no king of Israel in those days, everyone did what they thought was right in their own eyes”. To this end, all Christians were anarchists. In early press briefings it was stated that the object of the church was to “reorganise society so that mutual help and good may gradually supplant the state of warfare … cooperation would take the place of struggle’. Its’ plain-dress ministers — ditching the customary ruffles and gold of the High Church — might just as readily be glimpsed attending a meeting on Irish Home Rule as a scout club jamboree. There could no boundaries between countries. There could no rulers in those countries. There could be no property, no ownership. In fact, the Southgate Church’s place in the rapidly emerging class struggle was pitched somewhere between Circus Ringmaster, Greek Chorus and John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’. [6]

Although by no means a stranger to the church or the Nonconformity movement, Baker’s rise within its ranks was swift. The Church’s founder J.C Kenworthy had handed him leadership of the East End church shortly after returning from a trip to Moscow where, it was alleged, the Russian novelist and political reformer Leo Tolstoy had given Kenworthy full rights to publish English translations of his work. [7]

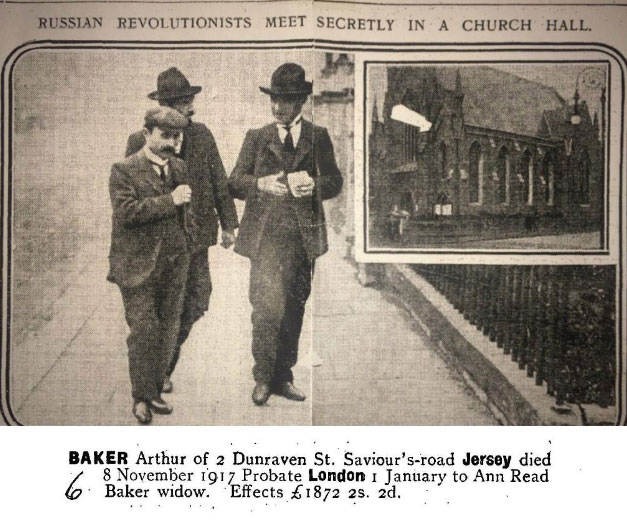

Father Arthur Baker and the Brotherhood Church on Southgate Road

Like Elvin, Baker had been born in Bombay. His father William Adolphus Baker was a respected general in the Royal Engineers who indulged in flights of outrageous religious prophecy based upon complex arithmetical calculations and morbid daydreams about the Antichrist. For several years William had served as the city’s Under Secretary of State, serving additionally as the director of the Ganges Canal Railways in the country’s Public Works Department. In May 1907, the 45 year old Arthur Baker invited Lenin, Stalin and Trotsky to the hall of his church on Southgate Road to host the 5th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party — a three week event, staged in thirty five gruelling debating sessions. These meetings, pulling together some 300 Bolshevik, Menshevik, Bundist and Baltic delegates, would play a pivotal role in advancing the truly momentous revolution in Russia in 1917.

As news of the secret meetings leaked out and the word spread, the press photographers had a field day. Crowds of gawping loafers and Special Branch detectives mixed freely with the swarthy cortège of ‘dangerous revolutionaries’. For the first few nights of the two week congress, Russia’s future President, Joseph Stalin is believed to have stayed at doss house on Fieldgate Road before being offered the relative comfort of a cramped first-floor apartment at Elvin’s former home on Jubilee Street. As the recently elected Secretary of the National Union of Clerks, one can imagine Elvin bunking off the various trade galas and meticulously minuted meetings and taking his seat in the chapel, overwhelmed by the ferocity and passion of debate, before creeping sheepishly back to the cosy sanctuary of his home in Buckhurst Hill.

Were either Elvin or Baker responsible for moving Stalin from Fieldgate Road to the flat on Jubilee Street? It seems plausible enough, although in later years Stalin himself would remain unusually quiet about his stay in London. Both men seemed surprisingly comfortable with villains, revolutionaries on the more visceral fringes of rebellion, Baker having already made the acquaintance of Manchester Anarchist and later Sheffield Trade Unionist, Alfred Barton, during his missionary work in Salford. A pamphlet written by Baker and published by the Socialist newspapers, The Clarion and New Moral World in 1896 paid tribute to the early Tolstoyan communities and co-operatives being popularized by the likes of J.C Kenworthy and the Brotherhood Trust. The Labour Chronicle even went as far to describe it as the ‘handsomest and most interesting series of pamphlets in the Socialist movement’. Baker’s follow-up publication, A Plea for Communism (1896) would go that little bit further, providing in one handbook, a ‘sound and practical guide’ to Communism built around tried and tested facts rather than theory. This ‘touching’ and ‘convincing’ series of sketches, published under the auspices of the Brotherhood Church, even featured a favourable review of Barton and William MacQueen’s ‘Free Commune’ in Chorlton on Medlock — a vibrant and experimental community that would be partially successful in knitting together the far-reaching philosophy of Nietzsche and Engels with the rich moral tapestries of Tolstoy. Barton, who joined the Communist Party of Great Britain upon its launch in August 1920, was on close terms with exiled revolutionary Prince Kropotkin whose pamphlets he would publish through the Free Commune Press in the late 1800s. MacQueen, meanwhile, would later be jailed in America for playing a leading role in the Paterson Silk Strikes.

Shortly after the conclusion of the 5th Russia Congress in June, Reverend Baker packed up his missal and Geneva gown and relocated to a Congregational Chapel in Truro, Devon, where he served until he resigned his post in 1912. From here he left the Channel Islands. In a deeply macabre twist it transpires that Baker, whose chapel had provided such a sound, compassionate birthing room for the Russian Revolutionaries back in 1907, died on the very same day that Lenin and the Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Palace in St Petersburg. The event would subsequently become known as the October Revolution (November 7th — November 8th on the English or ‘New Style’ calendar). The impact the two week congress in London had on the revolution shouldn’t be underestimated. What it did was compound the fractious rift between the moderates and the extremists, leading to the emergence of the Bolsheviks as a credible leading force. Peaceful regeneration was rejected in favour of violent revolution. According to the Manchester Courier of May 31st, the Extremists had finally ‘wrested control’. The man who had effectively performed its baptism died on the very same day the Revolution came of age. The champion chess player and speaker of 13 languages was dead at fifty-four. The date would be scorched into history forever: November 7th 1917.

Henry H. Elvin would eventually go on to become Chairman of the TUC in the late 1930s but much of his early energies had been poured into Clarion Sports. The Clarion-offshoot, the BWSF would provide the basis for ‘Labour Sport’ which in turn would form the basis of an international fraternity that would replace Militarism with Olympianism.

[1] Sport in Europe: Politics, Class, Gender, ed. J A Mangan, Taylor & Francis, 2013, p.33

[2] ‘New Advisory Committee’, Guardian, 21 Aug 1939

[3] A Cockney in Moscow, Harold Elvin, 1958. Harold (b.1909) was the youngest son of Herbert Henry Elvin and Mary Jane Elvin. His elder brother was educator, Herbert Lionel Elvin (b.1906). The 1911 census sees them living at Hollyhurst Queen’s Road Buckhurst Hill

[4] Sunday Post, August 6 1939, p.18

[5] Daily Herald, 27 June 1952, p.1

[6] Hackney and Kingsland Gazette 02 February 1894, p.4

[7] J. C. Kenworthy and the Tolstoyan Communities in England, W. H. G. Armytage, 1957