In September 1920, former Colne Valley MP and self-styled Socialist revolutionary Victor Grayson walked out of his plush apartment at the Georgian House in London’s St James’s, never to be seen again. Or at least that’s how the story goes. And we have two people to thank for that: 24-year old hotel manageress, Hilda Seager Porter and former Naval Intelligence man and journalist, Donald McCormick. The story they told was amazing; Maundy Gregory, theatre mogul and villainous honours tout had Albert Victor Grayson murdered for threatening to blow the lid on a cash-for-honours scandal that would have finished the career of British Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

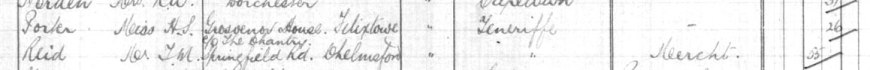

A closer look at the lives of Porter and McCormick, however, reveals some curious details in the pair’s respective backgrounds. In January 1922, Hilda Porter, whose story about Maundy Gregory was to prove central to McCormick’s claims of murder, made the first of two mysterious trips to the Canary Islands. Trips at this time were expensive and the 24-year old Porter was little more than a desk-girl. One round trip alone would have consumed more than three-quarters her annual earnings (Madeira & Canary Isles, Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 04 February 1922).

But to understand the real significance of the trips, we need to dig a little deeper.

Strange Goings-On at the Vernon Court Hotel

Hilda Seager Porter was born in Ipswich in 1895 to Henry George Jacques Porter, a senior accountant for Cliff Brewery and treasurer and chairman of Ipswich Conservatives. At the age of just 21, Hilda became the manageress of Vernon Court Hotel in Buckingham Gate. The hotel, whose intriguing list of patrons included soldier, explorer, mystic, guru, and spy, Francis Young, Radclyffe Hall’s lover Mabel Batten and Navy Commander Hartland Mahon, occupied a lofty and elegant position on the corner of Buckingham Gate and Palace Street. Several of the upper rooms overlooked the grounds of Buckingham Palace. It’s not entirely clear why Hilda was entrusted with such a responsible role at such a young age. A keen sense of discretion would certainly have been a prerequisite as this exclusive selection of suites had no shortage of spicy affairs to hide and Westminster-sized secrets to keep. Being just across the road from Buckingham Palace would also have presented considerable security challenges. The previous manageress had been Mrs Hilda May Southwell, a 38 year-old woman with a respectable 10 years’ of service behind her. Her salary was £50.00 a year. There were twenty bedrooms to keep and a staff of ten to manage (Chelsea News and General Advertiser, 27 November 1914, p.8).

In June 1917 Porter was brought before court as witness in the theft of treasury notes from a safe on the hotel premises. The accused was 17 year-old, Isaac Perelman, a porter at the hotel and the son of a Russian-born music hall artist (Chelsea News and General Advertiser 01 June 1917, p.3). It is believed that Perelman had gained a key to the safe and taken the money. He had been in England for little more than five years and was living on Commercial Road in the infamous Whitechapel district of London 1.

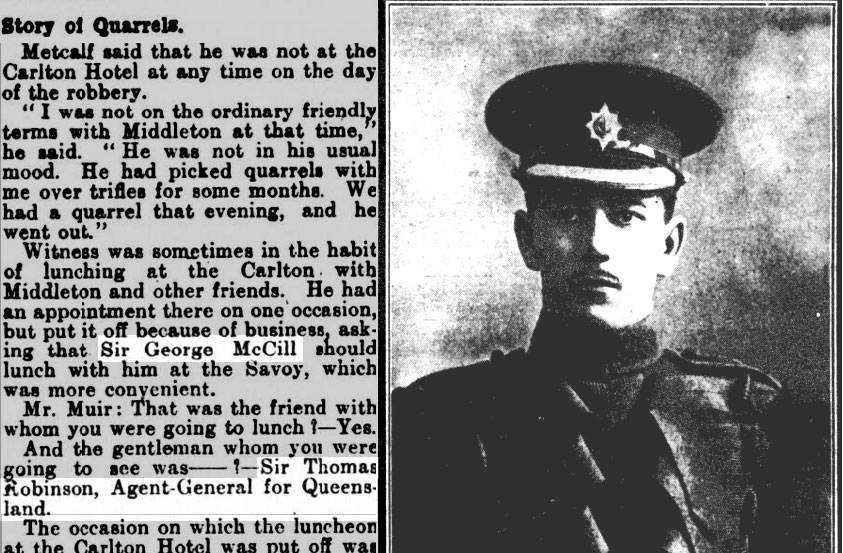

That same month Porter and the Vernon Court Hotel featured in another, more sensational heist, this time featuring a former officer in the Coldstream Guards. On this occasion the story went national. The names of the accused were former Coldstream officer, Theophilus James Metcalf, and Frank Milton, a handsome young private in the Royal Flying Corps who had recently deserted his unit.

The prosecution alleged that £7,500 worth of jewellery had been stolen from a showcase at the Carton Hotel and then stashed in a trunk in a guest room booked in the name of Metcalf at the Vernon Court Hotel, where Hilda Porter was now working as manageress. Milton had no means of his own and so Metcalf had bore the expenses of the rooms. The men were at arrested in a theatre box at the Comedy Theatre. The theatre was, coincidently, the same Comedy Theatre on Panton Street where Grayson’s actress wife, Ruth Norreys had found a regular job as understudy.

Florrie Middleton, Milton’s sister, who was found to have been receipt of the stolen goods, was employed at the British War Office and had stayed with the two men at The Petrograd Hotel in London. Florrie informed the court that her brother had been an actor and had first become acquainted with Metcalf in 1915. The detectives leading the investigation put the men under ‘close observation’ at their Vernon Court lodgings for some several weeks (Hotel Jewel Robbery, Globe 03 July 1917, p.7). According to reports of court proceedings, Metcalf’s father was the British Vice Consul of New York. Milton, on the otherhand, wasn’t Frank Milton at all, but Frank Middleton, son of a fish and game dealer in Penrith (Penrith Observer 24 July 1917, p.2).

The same three individuals were rearrested some three years later in May 1919 at the Naval and Military Hotel in South Kensington. Standing alongside them in the dock that year was Lieutenant Douglas Homewood Challenger Newth of the Royal Flying Corps (Globe 27 May 1919, p.1).

Interestingly enough, the same Douglas Homewood Challenger Newth re-emerges in the late 1940s as witness in the so-called ‘Lynskey Tribunal’ – a British corruption scandal featuring Labour’s John Belcher and Israeli Spy, Sydney Stanley (Aberdeen Press and Journal 30 November 1948, p.2). At the time of the affair, Newth was employed as temporary chief assistant under Graham Palmer at the Board of Trade. This is interesting, as his 1919 associate Theophilus Metcalf told the court in July 1917 that one of the men he and Milton dined with during their time in London was the Agent General for Queensland, Thomas Bilbe Robinson – a key figure at the Board of Trade in wartime Britain (Pall Mall Gazette 17 July 1917, p.5). The other man Metcalf mentions is more intriguing still; Sir George Makgill – the powerful and wealthy head of a private intelligence network and close political ally of Victor Grayson visitor Horatio Bottomley (The Peoples League). If this is correct, then it’s entirely possible that both Metcalf and Hilda Porter were on the Makgill payroll 2. Makgill and Gregory were both later accused of colluding in the fabrication of the so-called, Zinoviev Letter.

Was Grayson’s conscription drive in New Zealand in September 1916 in any way facilitated or encouraged by Makgill? Again, it’s a possibility. Makgill spent the formative years of his life in the country and had married into a wealthy New Zealand farming family during the early 1890s. Makgill and the British Empire Union had also launched belligerent propaganda campaigns against the No-Conscription Fellowship and the Anti-Conscription Council during this same period (Jarrow Express 07 April 1916, p.7). The pair may have little in common politically, but they were both fiercely pro-War. And as nephew of the former British Secretary of War, Lord Hardane, Makgill was certainly not without influence 3.

Middleton, a serial offender who’d left Penrith to work in theatre in Manchester in 1910 was charged and found guilty of similar fraudulent offences in 1928 and 1934 respectively. Metcalf was let off lightly with a fine.

The following year, Hilda Porter’s Vernon Court Hotel featured in another jewel-theft drama, this time featuring Captain William Herwell who had £80.00 stolen from his room by Music Hall entertainer, Gretano Alabano – a recent deserter from the army. The Captain was subsequently awarded damages by the hotel (Pall Mall Gazette 10 June 1918, p.8).

Curiously, on his release from the Canterbury Regiment, Grayson was intending to lodge at the Vernon Court Hotel but switched to the Georgian House on Bury Street at the last moment. Why Hilda Porter should make that same switch to the Georgian House that year remains a mystery, but this is where we find her next.

The Georgian House

Sometime in 1919 Victor Grayson, recently demobilized from the New Zealand Army, takes up residence at a smart and discreet apartment at the Georgian House on Bury Street. According to an advertisement placed in the Army and Navy Gazette in May 1916, ‘this magnificent new building’ combined all the luxuries and mod-cons of a 5-star hotel with the privacy of a house or flat. Every suite was fitted with a private telephone, tiled bathroom, and was steam-heated throughout. There were even special rates for officers on leave (Army and Navy Gazette, 27 May 1916). Porter maintains that over the course of several months, Grayson would entertain a small but notable coterie of guests and advisers that would include his old friends Robert Blatchford and Havelock Wilson, as well as more loathsome individuals like Horatio Bottomley and Maudy Gregory. Porter says that Grayson and she would occasionally visit the theatre and that during the course of his stay at the house, the pair became friends.

In an interview with Grayson’s biographer, David Clark made shortly before her death in 1984, Porter claimed that sometime between September 26th and September 28th 1920, two strangers arrived unannounced at the flats to see Grayson. Porter says the two men sent up their visiting cards to Grayson’s room and that some moments later Victor invited them up for drinks. After several hours the three of them are alleged to have come down from the room, entered the lobby and ordered a taxi. Grayson was carrying a suitcase. Grayson’s told Hilda that he would be going away for awhile and would be back in touch shortly. All three men, she says, left in a hurry (Victor Grayson: The Man and the Mystery, David Clark, 2016).

Without Porter’s eyewitness account, Donald McCormick’s claims of a murder and any subsequent cover up would lack much in the way of credibility. McCormick, a former Naval Intelligence officer and one time colleague of Ian Fleming, had a something of a reputation for habitually employing a technique of “fleshing out his book with uncheckable and bogus documents and statements.” (The Maybrick Hoax: Donald McCormick’s Legacy, Melvin Harris). His books about Lord Kitchener and Jack the Ripper employed the same dubious methods; a pinch or two of documentary evidence topped with lashings of anecdotal and totally unverifiable evidence.

What made his story all the more intriguing was the fact that McCormick’s uncle, Nonconformity minister Fred H. King – brother of Donald’s mother Lillie Louise – was living just minutes around the corner from Victor’s mother, Elizabeth in the Toxteth district of Liverpool in the time leading up to Grayson’s disappearance. Officially at least, Grayson was last seen at his mother’s house on Northbrook Street in the last weeks of September 1920 (Mercury 10 March 1927, p.1).

Both Grayson and his mother had been long serving members of the Nonconformity movement, the Liverpool-born Grayson having trained originally as Unitarian Minister in Manchester, shortly before his entry in politics in 1907. Between 1914 and 1920, McCormick’s uncle, Reverend King, was minister at the Toxteth Tabernacle on Park Road – a five minute walk from Grayson’s mother at 74 Northbrook Street. In a press advertisement in the Liverpool Daily Post dated 20 May 1916 the names of Fred H. King and Reverend Allen Holt, a close family friend of Grayson, appear in a list of speakers at the Central Hall Mission and Toxteth Tabernacle. Reverend Holt was the first person to make enquiries with the War Office on the condition of her son, after Victor’s mother had learned of her son being wounded in action in France (Victor Grayson, Service Records, WW1 45001 – Army, Archway Item ID:R116788436).

Curiously, Holt was also a friend of Liverpool pacifist, activist, actor and playwright, Frederick H.U Bowman, detained like Grayson ‘witness’ John Beckett under Defence Regulation 18B for his support of fascism in 1940s Britain (Frederick H.U. Bowman, Detentions under Defence Regulation 18B, LCO 2/2712, National Archives). Bowman — an eccentric of unknown origin who went on to become a creatively vexatious member of Beckett’s British People’s Party in the run-up to the Second World War — resided at his mother’s house on Duke Street, Liverpool. For the best part of his life Frederick served as senior correspondent for the movie theatre standard, The Bioscope and had long been connected with Holt and the Saturday Concerts at Liverpool’s Central Hall Mission. Films figured prominently in Holt’s programme of activities, Bowman describing his friend as a clergyman who was ‘broadminded and intellectual’. (Liverpool Round and About, The Bioscope, 17 May 1917, p.87)

The King and McCormick families had a formidable reputation in Unitarian circles. McCormick’s father, Wiltshire journalist Thomas Burnside McCormick, was himself a deacon at the English Methodist Church in Rhyl (Rhyl Journalists’ Death, Liverpool Evening Express, 10 May 1944, p.3). Donald’s evangelist grandfather, was the veteran preacher of Warminster, Samuel King, dubbed ‘King of Colporteurs’ by the Wiltshire Times in 1910 (Wiltshire Times, 19 November 1910, p.11)

Inexplicably, in 1921, an annual report from the Unitarian College lists Grayson’s name among those who had died the previous year. This is very peculiar. Until media interest in Grayson was revived in the late 1920s, the general assumption amongst Victor’s friends and family was that he had simply withdrawn from public life. It wasn’t until Victor’s mother and brother shared their increasing concerns with the press in the spring of 1927, that anyone had a suspicion that Victor had not just vanished, but died. Grayson’s biographer, Lord David Clark writes that the college’s principal, Dr Herbert McLachlan, had simply assumed that Victor had died, but why this assumption had been made remains a mystery. Clark quite rightly points out that the college had had no reason to assume Grayson was dead. Few even knew he was missing (Victor Grayson: The Man and the Mystery, David Clark, 2016, p.248).

More Queer Goings-On at Porter’s Georgian House

In the summer of 1921 Hilda Porter and the Georgian House were drawn into an altogether different kind of drama. This one took place in the divorce courts and featured Ethel Jane Blyth MBE, daughter of Sir John Brunner and widow of the late James Audley Blyth, heir to the Brunner-Mond fortune (the company later merged with several other chemical firms to form ICI). According to the divorce hearings, a Liverpool merchant by the name of Colin Woollham Anderson had rented a Georgian House suite and was conducting an affair with Mrs Blyth. The couple had met in Cannes the previous year. According to his wife, Anderson was also renting rooms at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool during this same period (Illustrated Police News 21 July 1921, p.2). The story became national headlines.

There are several threads that make the story unusual. The first is that there are the obvious links with Liverpool, Hilda Porter and the Georgian House. The others fall into the altogether more ‘tangled’ category.

Blyth was the daughter of John Brunner, a wealthy Industrialist and Liberal politician, who like the Liverpool-born Grayson, had strong links to the Unitarian and Irish Home Rule movements (both men were raised in Everton). In the 1870s Brunner (or Swiss heritage) had founded chemicals giant Brunner Mond and Company with German-born chemist, Ludwig Mond. Did Grayson introduce Blyth and Anderson to the swanky and frightfully discreet suites of Georgian House on Bury Street? It’s certainly possible. Like Grayson, Anderson had strong links with both British Government (Ministry of Food) and London’s theatre district. Grayson himself was an actor, as was his wife Ruth Norreys. Grayson’s best man Arthur Rose – born Louis Drachman to Russian refugees in the St. Giles district of Edinburgh in 1880 – was also a prominent stage figure. Described by Grayson biographer David Clark as a ‘committed Socialist’, Arthur Rose had earned a living as an actor-manager with a touring company in England, and was passionate about just two things in life: theatre and politics – often combining these unlikely obsessions in a devoted flurry of activity at the Actors Association and taking up the slack in controversial spin-off projects like the Play For Play League with German-born actor and diplomat, Eric H. Albury (The Era, 21 January 1914/Bioscope May 26 1921) 4.

The connections don’t end there. After his disappearance in September 1920, many people have speculated that Grayson lived out his days in New Zealand. Victor and his wife had often talked of emigration and it was here, during a tour with the Allen Wilkie Shakespearean Company, that Grayson enlisted with Anzac forces in the autumn of 1916. And it is also in New Zealand that Edith Jane Blyth and Colin Woollham Anderson — the two lovers at the centre of the torrid Georgian House affair — BOTH meet untimely deaths.

Blyth and Anderson had emigrated to New Zealand in 1926, Anderson plying his trade as a theatre owner and racing impresario. In November 1931 at the age of 50, Ethel Jane Blyth, who’d risked so much of her name and fortune over the affair, was dead. Ten years later, Hilda Porter’s Georgian House guest, Colin Woollham Anderson, son of a Glasgow Policeman, was also dead. The 66 year-old had been found poisoned at his home in Kohimarama near Auckland. A verdict of suicide was returned (Suicide Verdict, Theatre Manager’s Death, Evening Post, 11 March 1941). It was alleged that Anderson had been depressed and unable to sleep. The port-mortem examination revealed appearances that were consistent with cyanide poisoning.

Blyth’s life was dogged by tragedy from start to finish. Her first husband James Audley Blyth had died in very mysterious circumstances in South Africa in 1909. James had been on Safari with Ethel and swashbuckling soldier and adventurer, John Henry Patterson. Many suspected Patterson of his murder, whilst others suspected Ethel, whose friendship with Patterson is said to have blossomed during the trip. Within months of Blyth and Anderson’s move to New Zealand, her brother Roscoe Brunner, chairman of ICI – at the centre of various ownership and direction battles – featured in a grisly murder-suicide at the home of Prince Ferdinand Andres de Lichtenstein in Putney, London. Many suspected foul play and the partner of Ethel’s father, Sir Alfred Mond came under scrutiny. The millionaire ex-chairman of Brunner Mond and Co had been shot in the head with the body of his wife, the well known author Ethel Houston Brunner found by his side (Mr. & Mrs. Roscoe Brunner Found Shot Dead, Daily Mail November 04, 1926; pg. 9). It was ruled a domestic tragedy but if this was truly the case, then why has the official Brunner file been classified within the Royal and State Archives and locked away under Britain’s Hundred Years Rule until 2026?

Just to add to the layers of intrigue, Sir Alfred Mond (Lord Melchett) — Ethel’s father — had earned himself no shortage of notoriety for offering financial support to Russian Revolutionary Pinhas Rotenberg, regarded by many to have murdered Father Georgy Gapon, leader of Russia’s much less successful 1905 Revolution. Although raised in Liverpool, Mond was of German extraction. You can read the story of Father Gapon and Mond’s Radical Liberal colleague, Philip Whitwell Wilson (whose family home in Percy Circus played host to Lenin in 1905) in this separate blog article. It may be of interest to note that both Brunner Jnr. and Whitwell Wilson had both led the committee of the Cambridge University Liberal Club.

In a further tragedy, Ethel’s eldest brother, Sir John Fowler Brunner died just three years after his brother in 1929. The 63 year-old MP was contesting his seat in the Cheltenham By-Election at the time of his death. The death of Ethel herself some three years later marked the end of the Brunner dynasty.

Within months of the ICI chairman’s death in 1929, and with Mond at the head of the company, Saul Bron and ICI had cleared the path to sign a multi-million pound deal with Stalin’s Soviet Union (Aberdeen Press and Journal, 21 April 1930, p.5).

Hilda Porter Sails to the Canaries

If there was one reason to believe that ubiquitous receptionist, Hilda Porter may have been on the Intelligence payroll, it is that despite earning as little as £50 a year as a hotel manageress, each of two trips she made to the Canary Islands in the first six months of 1922 would have cost in excess of £1000 in today’s money (about £30-37 in 1922) 5. Another Westminster regular making trips to the Islands at this time was 25 year-old Makgill recruit — John Baker White, an early member of the British Fascisti whose own colourful espionage career is regaled at length in his 1970 autobiography, True Blue. John Beckett and British Fascisti founder, Rotha Lintorn Orman also making regular trips to the Island, and it may be worth noting that Baker White’s wife, Sybil Irene Graham shared an Elm Park Gardens address with Orman at the time her husband was being enlisted into the Fascisti and Makgill organisations. And significantly perhaps, Lintorn Orman spent the last few years of her life in Las Palmas, where Porter was heading.

Porter’s first trip to the Canaries is made in 1922. The ship was the St Margaret of Scotland and it sailed from London to the port of Las Palmas in Gran Canaria in the last week of January. The second trip took place in June, when Hilda sailed on the Garth Castle to Tenerife. On the second trip she travels with a ‘T.M Reid’ born 1867. The home address that Reid provides is Springfield Road in Chelmsford, the location of the Empire Theatre – owned by theatre owner and movie distributor Clifford Stuart Reid. Little is known about Clifford Reid. There’s certainly no trace of his birth in the records listed under any of the details revealed during his lifetime.

We see Clifford Reid for the first time in the 1911 census occupying a room at a modest lodging house run by Arthur Poulton and his wife Rose at Regina Road, New Street, Chelmsford. A kinematograph operator from Skipton and a vocalist with the Lyric Company are lodging with him. The census sheet lists him as ‘Clifford Stuart Reid’ born in Peterborough, Cambridgeshire in 1883. His occupation is recorded as ‘Theatre Manager Proprietor’.

Reid later informs the press that he is the son of a well-known veterinary surgeon in Norfolk who spent much of his youth as an apprentice to a photographer in Nottingham before running an unsuccessful studio of his own. A little time later Reid claims to have become a boy ventriloquist, performing regularly at Manchester’s Tivoli Theatre. According to a report of an after dinner speech made in November 1912, Reid says he was offered a post as manager at the Springfield Palace theatre in Chelmsford, before re-launching it as the Chelmsford Empire and Hippodrome with J.O Thompson in 1912 (Chelmsford Chronicle 22 November 1912, p.2).

In July 1917 Reid enlists with the Royal Navy, serving first at Crystal Palace before transferring to Royal Navy Airplane Base, HMS Daedalus near Calshott in January 1918. He is promoted to a Corporal in the Royal Air Force that July. On his service records he lists his date and location of his birth as July 14th 1881 in Peterborough (his spouse is listed as Mary Ellen Reid of Gravesend, but again I cannot find a credible match in the BMDs records). Contrary to what he claims, the spelling of the name ‘Reid’ suggests Scottish heritage.

Shortly after being demobbed, The Bioscope cinema journal reports Reid’s appointment as manager of the Royal Cinema in Belfast (11 September 1919 – The Bioscope – London, London, England, p.95) From here he finds employment as Regional Manager with Ideal Films Ltd in Dublin (The Bioscope 27 May 1920, p.9). Interestingly, the company’s founders, Simon and Harry Rowson (born Rosenbaum to Russian immigrant parents in Manchester’s Cheetham Hill) played a key role in a legendary biopic of David Lloyd George, shelved rather unceremoniously in 1918. The film’s screenwriter was journalist and historian, Sir Sidney Low and its director, Maurice Elvey. Low’s niece incidentally, was Ivy Low Litvinov, wife of the Bolshevik minister Maxim Litvinov.

Originally entitled, ‘The Man Who saved The Empire’, the film’s ambitions took a major blow when Grayson’s Georgian House visitor, Horatio Bottomley accused the brothers and their partner, Sara Wohlgemuth — wife of Glasgow photographer Benjamin Wohlgemuth — of radical and unpatriotic intent; they were accused of being German Spies (The Manchester Guardian, 14 Dec 1918, p.9). The men responded with a writ for libel but it was all a little too late; Lloyd George wanted the film suppressed. According to the Rowson Brothers, £20,000 in cash was handed over to cover the costs of film production and the negatives and the prints were seized.

That Madeira and the Canary Isles would subsequently become a base for a German spy networks only adds to the layers of intrigue. Was it just a coincidence that one of the first movie features that Clifford Reid unveiled to audiences at Chelmsford’s Palace Theatre in 1911 was a propaganda film featuring British Secretary of War, Lord Haldane during a visit to the town on Trafalgar Day? Uncle of the deeply mysterious spymaster, George Makgill? (Chelmsford Chronicle 27 October 1911, p.5).

My own hunch is that is that Reid may have been associated with Ideal Films’ Rowson Brothers and their Glasgow partners, Sara and Benjamin Wohlgemuth as early as 1910. There is report of a ‘Clifford Stuart Reid’, a variety artist of Brighouse, Leeds, assaulting a Simeon Joseph Henry on stage in Halifax (Sheffield Evening Telegraph 26 February 1910, p.6). That Jane Bernstein, a founding partner in Ideal Films was herself from Leeds and that the company had one of their first formal bases in Leeds makes it an attractive possibility, but it is by no means certain. The Bernstein family certainly had strong links with Empire Theatres and there’s every chance that Jane was the mother of Granada TV founder, Sidney L. Bernstein, who was general manager of Empire during the early years of the 1920s (Sidney’s mother was Jane Bernstein, born 1873, wife of a German-born estate agent Alexander Bernstein).

Reid died at the age of 56 in Elham near Folkestone in 1938.

After further exploration there is good reason to believe that the ‘T.M Reid’ accompanying Hilda Porter on her trip to Tenerife in 1922 is either a relation of Clifford or, at the very least, the inspiration behind his name. ‘T.M Reid’ was Scotland-born wine and timber merchant, Thomas Miller Reid, born 1867 — British Vice Consul of Orotava. Thomas was the son of Britain’s previous Vice Consul, Peter Spence Reid aka Don Pedro banker, merchant and steamship agent (1830-1916). Thomas sailed on that same route twice a year, often using the initials ‘T.M Reid’. Another name on the ship’s manifest for the same trip is a Miss Sheldon, daughter of architect and County Surveyor Percy J. Sheldon of The Chantry, Springfield Road, Chelmsford. According to a press report in 1917, Reid’s son, the Royal Air Corps ‘flying Ace’ Captain Guy Patrick Spence Reid had been engaged to Miss Sheldon shortly before his death during a training exercise in Lincolnshire (Essex Newsman 20 October 1917, p.2). The differences between the two addresses in Springfield is about 120 yards and it is interesting to note that the girl’s father, Percy Sheldon was active in Jane and Sidney Bernstein’s hometown of Ilford (Ilford Recorder 15 July 1904, p.5). Additionally, Clifford Reid’s partner in the Chelmsford theatre builds was deputy mayor, J. O. Thompson. Thompson was close friend and council ally of Mr Sheldon and both men were active organisers of the Comrades of the Great War meetings held at Clifford Reid’s Empire (Chelmsford Chronicle, 14 December 1917). Given his meteoric rise from obscurity, perhaps ‘Reid’ was little more than a ‘nominee’ or ‘front’ director with control and direction of the enterprise lying with Thomspon and other ‘invisible’ shareholders.

Look at it this way; one year Reid is a brawling projectionist in Leeds Brighouse, the next he is the respectable manager of a chain of Empire Theatres spanning Chelmsford, Dover and Folkestone.

Maybe there is a link between both sets of Reids and Porter. Maybe there is none. One thing is certain, the shape of the worlds they inhabited seems to have been fashioned from the same voile fabric that produces the lustrous drapes of Reid’s theatres.

Hilda Porter and Grosvenor House Mystery

As if things weren’t peculiar enough, we discover that the address Hilda Porter uses on the ship manifest in 1922 — the Grosvenor House, Felixstowe — features in another unsolved mystery dating back to October 1901.

Mr John Howard Bulleid, a solicitor with Cooper & Co in Newcastle-under-Lyme was found dead under a hedge in Long Lawford near Rugby. A bottle of the opiate, Chlorodyne was found by his side. The previous day he had been in London. No one knows what business he had in Long Lawford, just as no one knew what business he had in London. The man he had met in London, Charles Bull of Rugby Chambers on Great James Street, could not account for the man’s visit. Police found a number of partially burned items beside a little fire that Bulleid had lit on the grass. Among the items Police found were a note bearing the name of Willesden medical practitioner Walter W Stocker, a circular with the name of the actress Violet Cartmell on it and two pieces of paper with the words ‘Grosvenor House, Felixstowe’ (Central Somerset Gazette 12 October 1901, p.4). Little is known about any of them. Dr. Stocker, who may have some previous links to Newcastle-upon-Lyme, was related by marriage to musician Eduard de Paris, a Brighton-based musician and associate of Wilhelm Ganz (1833-1914) a German conductor and violinist who had escaped from the continent in 1848 and spent much of his life in London. Violet Cartmell was a member of the Actors Association and the Grosvenor House in Felixstowe (close to where Hilda was born) appears to have been a private residence come hotel, standing across from the Ranelagh Gardens on Felixstowe sea-front.

There was another thing. Just several months before his death in Rugby, John Howard Bulleid had featured in the equally mysterious passing of his friend, John Leslie Thompson of Brecon. It appears that within hours of the friends checking into the Grand Atlantic Hotel in Weston-Super-Mare, Thomspon — manager of several joint ventures in Birmingham — was found in a semi-conscious state in his guestroom. Medical aid was provided but after showing signs of improvement the man collapsed. The cause of death was ‘syncope’ or heart failure, possibly brought on by an overdose of laudanum (Western Daily Press 22 February 1901, p.3).

A closer look at Bulleid’s life reveals that his father, John George Lawrence Bulleid was actively involved in Liberal Politics, as was his brother G.L Bulleid, a painter, whose works had been purchased by several members of the British Royal Family, as well as Kaiser Willhelm (Central Somerset Gazette 24 March 1933, p.5). G.L Bulleid was, by contrast, a member of the anti-Communist and anti-Socialist Junior Imperial League.

As peculiar as it sounds, Hilda Porter’s links to Grosvenor House do stretch back to this period. According to Porter’s great nephew, Trevor Darge, Hilda’s father Henry George Jacques Porter had formed a partnership with Mr Walter Mason Cuckow shortly after his arrival in Felixstowe in 1911. Grosvenor House had been in the Cuckow family for a number of generations, and was certainly in their possession at the time of Bulleid’s mysterious death. During the early part of his life, Hilda’s father had, like Reid, lived in the same Springfield district of Chelmsford with his own parents — workhouse schoolmaster and schoolmistress, George and Sarah Jacques Porter. Cuckow was, by contrast, a wine merchant who had been co-proprietor of the Grosvenor with his father Edwin since the 1880s.

Curiously, both Porter and Bulleid, the solicitor who died, were accountants by trade.

Epilogue

Despite talking to Grayson’s biographer, Lord David Clark in the early to mid 1980s, Hilda Porter was spared the media interest in the Victor Grayson mystery that was revived in with the broadcast of a TV documentary on the 65th Anniversary of his disappearance. The Curious Case of Victor Grayson, directed by Morris Baker was broadcast by the BBC in October 1985. Retired property manageress, Hilda Seager Porter passed away at Brunswick Mansions in Hove on August 30th 1984. She was 90 years old. Clark’s book, Victor Grayson: Labours Lost Leader, featuring his interviews with Porter was published the following year.

1 According to the 1911 Census, his address on Commercial Road, 3 Martin’s Mansion, had previously been home to Russian-born actor, Morris Beringarten

2 Makgill’s Anti-German Union (later the British Empire Union) was based at 346 Strand, just around the corner from the Georgian House. Grayson had been a fierce campaigner on anti-German military build-up since his days in Parliament in 1907.

3 Grayson & Mann’s’s friend, E.J.B Allen (Ernest John Bartlett Allen) sub-editor of The Syndicalist emigrated to New Zealand in 1913 to become editor of The Maoriland Worker, a newspaper that played a crucial role in Grayson’s wartime development and pro-war campaigning.

4 Eric H Albury was born Henry Rothenburg in 1879. He had spent his early career working for the British Government’s Cape Colonial Services, attached to the High Commissioner of South Africa, Joubert Brunt. During the war Albury had served with the 3rd (Reserve) Wessex Field Ambulance R.A.M.C. under his family name Private Henry Rothenburg (2202). He served in Germany and suffered gassing. He was demobbed in August 1919 and was subsequently was taken on by Stoll Pictures.

Robert Blatchford’s trips to France in 1909 to observe the German Military build-up first-hand for the Daily Mail, may have been facilitated by an associate of Arthur Rose. Chesterfield’s William A. Bond, was sub-editor at the Huddersfield Examiner before taking up a job as Paris correspondent at the Daily Mail. Bond at the time was romancing a feisty young journalist friend of Rose called Aimee Stuart (born Amy McHardy in Glasgow). The pair went on to write ‘The Lady from Edinburgh’ together. Bond became a Flying Ace with the Royal Flying Corps in 1916. His Chesterfield friend, Edwin Swale joined him at the RFC. The Swale family were likewise quite radical (Seth Swale becoming an active member of the Rationalist and Free Thought Society).

5 An assistant manageress in Bath was advertised at £50 per year in 1924.

Additional Sources

Wedding and Presentation, Lille King marries Thomas Burnside McCormick, Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 23 July 1904, p.3

Mystery of Victor Grayson, Leeds Mercury 10 March 1927, p.1

David Lloyd George: The Movie Mystery, ed. David Berry, 1998

The Vanishing MP, Sunday Times Magazine (great Grayson website)

Felixstow, Ipswich Lettering (for pictures & info provided by Trevlor Darge)