How Max Gerlach became associated with Arnold Rothstein isn’t clear. There is an eight-year period in Max’s life, starting 1912, when his exact location and activities are the subject of much speculation. This becomes clear in the report put together by Agent Harry W. Grunewald in the summer of 1917. After serving with the Atlantic Fleet at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and a shorter stint at the Brooklyn Navy YMCA, Grunewald had found himself being head-hunted by US Congressman and Democrat, Murray Hulbert. Within weeks of being introduced to Hulbert he was being hired by Hulbert’s friend, Charles F. DeWoody, Chief of the Department of Justice Bureau in New York who gained some notoriety for helping boxer Jack Johnson escape a jail sentence for dating a white woman, and the far less progressive round-up of US Army draft ‘slackers’.

In April 1917, the tough-talking 27 year old began his work as an agent on $3.50 a day at its Bureau of Investigation in New York, his fluency in German and his broad knowledge of German affairs bagging him a leading role in tracking down German spies. According to Fred C. Kelly, a journalist come investigator who had assisted Grunewald in some of the Bureau’s more outlandish plots, the agent and his men had once been responsible for spiriting a way a vast collection of secret papers belonging to the German Embassy. For this the men had been forced to temporarily resign their commissions and burgle the Swiss Consulate where the papers were being held. Another plot had Grunewald impersonating a German agent to crack the cover of another German agent in Cuba. Posing as friends, Grunewald and Kelly had lured the man’s wife to a fake office at Union Square and quizzed her about her husband. The wife is believed to have been so taken in by the pair’s performance that she blew the lid on everything. On another occasion the wonderfully talented ‘G-Man’, posing as a ‘Mr Grimm’ spearheaded a similar ruse on a deeply embedded German agent who was suspected of stealing navy and aircraft documents from navigations company, Sperry Gyroscope. To all those who were on the right side of law and the right of the war, this unusually clever agent was known as a rough and tumble, two-fisted spy-hunter who was capable of being all things to all men — jovial yet stiff-jawed, creative but task-driven. One minute he could be smiling and cracking jokes, and the next he might very well have you in a headlock. It wasn’t some minor gambling or bootlegging offence that interested Special Agent Grunewald in Gerlach; he was attempting to cast some light on Gerlach’s ‘German Activities’.

It isn’t exactly clear what led him to Gerlach. The report merely states that Max was believed to have been expressing sentiments that might have been perceived as vaguely anti-American and how he had also been a personal friend of Major Ryan at the American Embassy in Berlin during the first six months of the war. Grunewald was unlikely to be in the habit of grilling every German-born American saying bad things about Uncle Sam, so it is probably safe to assume that his decision to question Gerlach was based on a more specific lead he was following up in one of his many spy-busting operations. At the time that he compiled his report, Grunewald had been busy building a case against New York anarchist, Emma Goldman. Grunewald and the Justice Department had apparently come up with ‘evidence’ that showed that Goldman and her husband, Alexander Berkman had been cooperating with German spies in foreign countries to stir up rebellions in India. The ‘evidence’, which was typical of the time, chiefly consisted of Goldman’s objection to the British Raj and the anti-war message that she and Berkman were pushing at home. Nevertheless, a number of requests for aid made by Indian Nationalist Revolutionary, Har Dayal in Berlin, believed to have been found among letters at their home, were viewed as proof of ‘collaboration’.

As Grunewald looked into Goldman, he was also looking into several other notable figures in the Jewish-dominated Second Avenue, and it is quite possible that Arnold Rothstein was amongst them. The investigation would eventually bring Grunewald into contact with Broadway impresarios, J. L. Costello and Freeman Bernstein whose impressively broad network of contacts and distribution channels would help the Federal US Government thwart a plot by German spies. The spies, it was alleged, would place messages in movie-reels and then ship them to neutral Holland to communicate with agents back home. [1] Grunewald’s attempts to speak to Gerlach at his 700 Broadway address in the summer of 1917 — a location that may have been linked to his motor business concerns with Rothstein’s legal counsel and ‘fixer’, George Young Bauchle — had proved futile. [2] A search was made of the premises, further associates were quizzed, but there was simply no trace of him. Grunewald had better luck at his address at West 38th Street, home of the New York Institute of Photography. [3] The official report suggests that Grunewald’s investigation into Gerlach had been triggered by some ‘pro-German’ remarks that Max is alleged to have made. Who shared this information wasn’t unspecified in the agent’s report.

When interviewed, Gerlach very calmly cleared up any confusion about his birth, telling Grunewald that he had been born in Yonkers, New York in 1885 and that his father and mother had been born in Germany. When pressed about the change of his name his response was no less prosaic: his father had died and his mother had remarried. Max’s story seemed so straightforward. In 1913 he had gone back to Germany and returned the following year. The extent of his ‘German activities’ consisted mainly of visiting relatives. The next bit was a little more interesting. Max confirmed that his father, Ferdinand von Gerlach, had indeed been a Lieutenant in the Royal Prussian Army as Grunewald’s informant had alleged. A report compiled by the American Protective League the following year added a few more details. According to Gerlach, his father had served as some kind of ‘secretary’ in the Royal Court of Friedrich III — the father of Kaiser Wilhelm. It may have all seemed little grey and unsensational, but what Max was telling Grunewald was a confusing mixture of truths, half-truths and plain old lies. According to research undertaken by Professor Kruse in the mid-2000s, Max’s father does appear to have served Friedrich III in some capacity. Records retained from the archives of the German Royal Court reveal that a Ferdinand Gerlach served as Geheimer Kanzlei-Sekretar (Inspector of the Secret Chancellery) in the Ministry of the Royal House of Hohenzollern in Berlin sometime between 1874 and 1877. If it was anything like the Secret Chancellery of Austria or Imperial Russia, then the ‘Geheimer Kanzlei’ was the seat of espionage and state police — the department of intrigue. Extraordinarily enough, the one thing that Max seemed a lot more anxious to lie about was the country of his birth. Gerlach had not been born in America but in Germany. Gerlach did, however, confess that he had been back in Germany as recently as 1913 and 1914. Although the report fails to identify the exact reason for Gerlach’s visit, it does tell us that he secured his passport back to the United States through his friendship with a Major James A. Ryan, an associate of Ambassador Gerard at the US Embassy in Berlin. After spending some 12 months in Berlin, Gerlach says he applied for his passport back to the US in August 1914. [4]

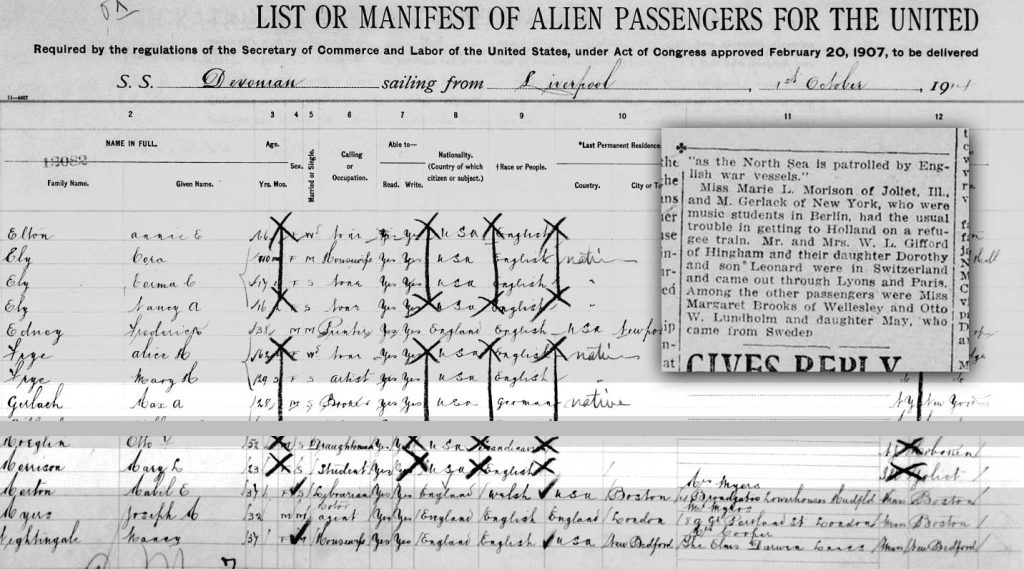

According to travel records, Gerlach left Berlin in October 1914, spending some three weeks in Great Britain before continuing his journey back to the United States. The ship manifest for the trip on the SS Devonian shows that Max left Liverpool for Boston on October 1st. Accompanying him on the journey was 23-year old music student, Mary L. Morrison. [5] There are two reasons that we know the pair travelled together. The first reason is that Gerlach uses the young woman’s home address for his passport application: 309 Sterling Avenue, Joliet, Illinois. The very same address appears in the US census of 1910 and shows Morrison, a ‘musician’, living here with her parents. [6] On the ship manifest Max A. Gerlach lists himself as ‘broker’ but enters ‘German’ in the field marked ‘race’. Why Max did this isn’t clear, but it may be a subtle indicator of where his loyalties lay in the first few months of the war.

Some, but not all, of the details regarding Gerlach and Mary Morrison are repeated in a newspaper report that the pair featured in upon their arrival in Boston. On October 11, the Boston Sunday Post told the grim and tragic story of how 49 year-old Annie Robinson — a survivor of the Titanic disaster — was presumed to have drowned in the last hour or so of the journey. It is believed that poor old Annie had jumped into the water as the SS Devonian had entered port after its 3,000 mile trip from Liverpool to Boston. According to the press report, the ship had started groping through a dense, unsettling fog in the last few hours of transit. It was speculated that Annie, perhaps restless and agitated by the sounding of the ship’s horn and by memories of the Titanic, may have panicked and fled the ship. It was only her absence at the breakfast table that alerted the Captain that anything untoward had happened. Nobody witnessed the leap, but the Captain had concluded that it was the only possible explanation. After the Titanic disaster Annie’s daughter Gladys had settled in Boston with James E. Prentis, son of the former American Consul, Thomas Theodore Prentis. She was on her to see her at the time of the incident. It was only Annie’s absence at the breakfast table that alerted the Captain that anything untoward had happened.

Nobody witnessed the leap, but the Captain had concluded that it was the only possible explanation. The press report went on to describe how the vast majority of passengers were Americans who had managed to secure their passage to the United States as part of the American Relief Fund. Some four months earlier war had been declared, and many of those sailing had been caught in the crossfire in Europe. Among those interviewed by reporters as the passengers disembarked in Boston were Max A. Gerlach of New York and Mary L. Morrison of Joliet — both of them described in the article as “music students in Berlin”. [7] What happened between Max’s return from Berlin in October 1914 and Grunewald’s investigation in June 1917 isn’t known. The only clue about Max’s activities between October 1914 and enlisting with the US Army in August 1918 are the references he provides from two known Rothstein associates: Judge Aaron J. Levy and George Young Bauchle, the gangster’s partner at the Partridge Club and high profile attorney among the ‘Old Money’ families of New York. The employment record that Max enters on his Army Application ends rather mysteriously some six years earlier in 1912.

Baron von Gerlach and Hallam Keep Williams in Havana

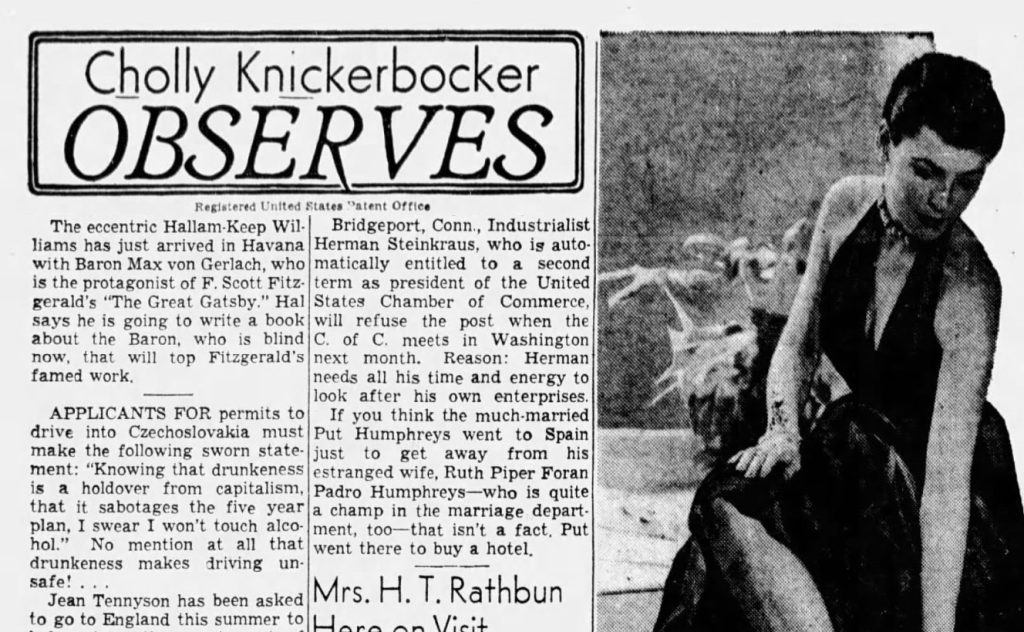

During research carried out for an upcoming podcast, veteran New York journalist, Joe Nocera shared some tantalising new information. A brand new report had come to light. According to a story published in the San Francisco Call in April 1950, ‘Baron Max von Gerlach’ had arrived in Havana, Cuba with “the eccentric Hallam Keep Williams”. Despite the report being no more than 40 words in total, the newspaper had a bombshell claim: the 65 year old Gerlach had been the original inspiration for the hero of The Great Gatsby and Williams was going to write a book about the Baron “that would top Fitzgerald’s famed work”. [8] The news came just three years after Zelda Fitzgerald is alleged to have told Princeton researcher, Henry Dan Piper that some Teutonic-looking bootlegger called ‘Guerlach’ had been the inspiration for husband’s fictional creation, Jay Gatsby. It also came hot on the heels of the 1949 movie remake of the novel starring Alan Ladd and Betty Field. Ever since the novel had been republished for American troops in 1945 there been a sharp revival in interest. If ever there was a good time for Max to tell his story, it was now.

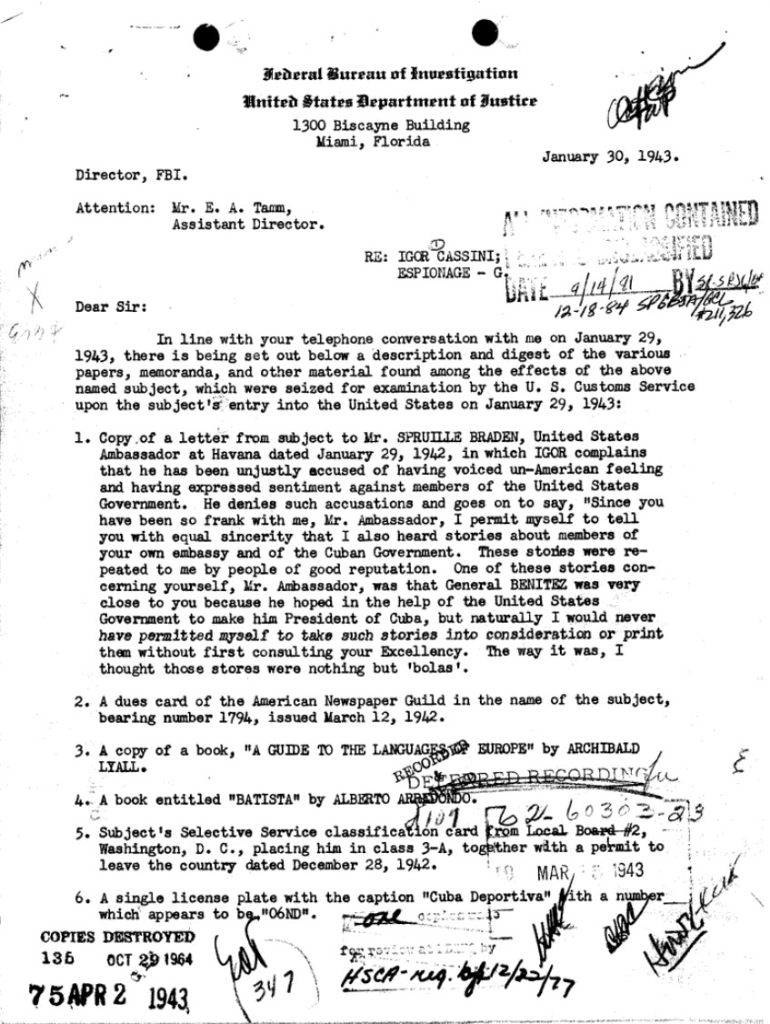

The man behind the Gerlach story was ‘Cholly Knickerbocker’, the pseudonym used by powerful ‘smart set’ gossip-columnist, Igor Cassini for New York Journal-American, a paper owned by his onetime father-in-law, William Randolph Hearst. Cassini, an aristocratic Russian whose grandfather had served as Russian Ambassador to Washington at the time of Theordore Roosevelt and William McKinley, would eventually face criminal charges for having failed to register his interests as a paid agent of Spanish dictator, Rafael Trujillo and the Dominican Republic. The dictator, whose autocratic empire had been build-up partly in collusion with Arnold Rothstein’s men, Frank Costello and Meyer Lansky had been a thorn in the side of America for years.[9] According to reports compiled by the FBI in 1943, Cassini, an uncompromising anti-Communist, had been in receipt of a number of grace and favour benefits from General Manuel Benitez — then serving as head of the National Police in Havana — and several other Cuban notables. Rumours were also circulating that ‘Cholly’ had been voicing ‘un-American’ sentiments. [10] Cassini reviewed the trip in his 1977 autobiography, ‘I’d Do It All Again’, rejecting any suggestion that he had been expressing un-patriotic views and pointing out that he had been invited back to Havana under President Eisenhower just a few years later. Cholly’s host on that second occasion, the US Ambassador, Earl E. T. Smith, did, it must be said, share the columnist’s abject loathing of the Liberal-backed dictator, Fulgencio Batista, and so he was there amongst good company.

Gerlach made numerous trips to Havana over the years — invariably arriving at times of political or social turmoil or transition. This time was no different. Cassini tells us that Gerlach had arrived with the 43-year old eccentric playboy, Hallam Keep Williams in mid-April, but this wasn’t the only trip that Gerlach had made to Havana that spring. Max appears on a flight manifest dated March 26th 1950, travelling back from Havana to Idlewild International Airport in New York. When Gerlach booked the flight, the airline, Linea Aerospostal Venozolana (LAV), had been promoting itself in ads as a ‘luxury’ direct flight linking New York with Havana and the sunny Venezuelan capital of Caracas. Money must have been no object to Gerlach, because no sooner had he arrived back in New York in March than he was back in Havana with Williams again in April. It is equally interesting to note that ‘Baron’ Gerlach and Hallam Keep Williams had arrived in Havana just in time for the First Inter-American Conference for Democracy and Liberty, a series of talks and lectures that had been organised to promote the ideals of American democracy to its South American neighbours. As Batista’s corrupt government began to show signs of collapse and the warlords moved in, America was keen to promote credible alternatives to fascism, communism and the oligarchic dictatorships of military strongmen like Trujillo. [11] A few years later, Igor Cassini, still writing as Cholly Knickerbocker, would recycle the whole ‘Inter-American’ brand for his pro-Trujillo lobbying agency, “Inter-American Public Relations Ltd” — a clear attempt by Cassini and his friends to wrestle the spirit of pan-Americanism from the arms of the American Left and Roosevelt’s New Dealers. It is not without some irony that Max von Gerlach, the man who was promoting himself as the patron saint of the American Dream, Jay Gatsby, had found himself in Havana just as America was planting the seeds of the dream in the poor, ungiving soils of South America. With the release of the Paramount remake of Gatsby starring Ladd the previous summer, the time had never been more ripe. [12]

Berlin 1914 – Max at the Opera

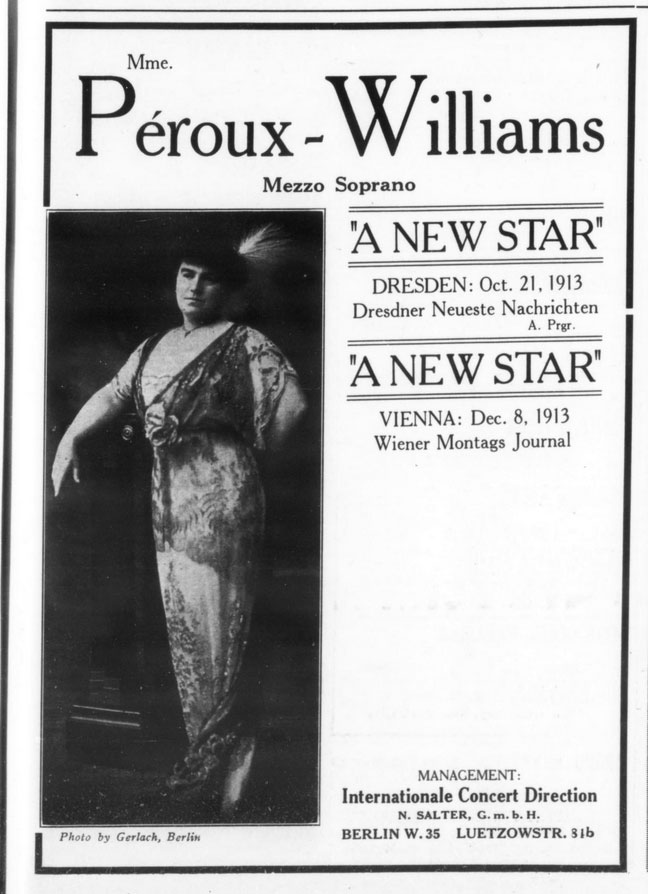

Based on Joe Nocera’s discovery about Gerlach and Hallam Keep Williams, I was able to determine that Hallam’s mother was none other than Alice Peroux-Williams (aka Alice Perew Williams, b.1871), an American opera singer who was active in Berlin at the same time as Max Gerlach. Records show that Alice, a gifted mezzo-soprano singer, had separated from her husband, the Buffalo-based stockbroker, Gibson Tenney Williams, shortly after the birth of Hallam in 1907. In 1909, Alice moved the family to Berlin, where she resided for some twenty years or more, returning only occasionally for concert tours of the States and special shows at the Carnegie Hall. [13]

In 1914, Hallam’s father Gibson married his second wife, Rhode Island music student and teacher, Florence Alice Smith (b. 1881) in Rochester in England after spending the previous five years shuttling between London, Germany, Italy and New York. They tied the knot on July 22, just six days before the outbreak of war. Gibson and his wife left Britain and returned to Germany sometime in late October. It was their intention to spend the winter in Munich, away from their base in the Bavarian alps. [14] Gibson’s time in Munich was marked by a new diplomatic crisis, when Irish-American Nationalist, Thomas St John Gaffney was forced to resign his role as US Consul General in Munich for expressing frank pro-German sentiments. It was also alleged that Gaffney had links to human rights activist, Sir Roger Casement. Back in Britain, Casement had been charged with high treason for the role he was believed to have played in the shipment of illegal arms between Germany and Irish Nationalists. [15]

On October 14 1914, Max Gerlach arrived in Boston aboard the SS Devonian with music student, Mary L. Morrison after a stay of some three weeks or more in London. Gibson Tenney Williams, the father of Gerlach’s friend Hallam, returned briefly to the United States in the autumn of 1917 when he gave a series of lectures to students revealing the ‘bare truth’ of the ongoing war in Europe and the true nature of conditions in Germany, France and Switzerland. [16] According to Professor Kruse, Gerlach was in England at least twice during this period. A passport application from 1916 states that Gibson first arrived in Germany in November 1913. The place that he made his home was Oberammergau, a tiny Catholic enclave on the Austrian-Swiss border. [17] When America entered the war in 1917, Gibson surrendered his services to the American War Relief Society of Geneva, then operating under the auspices of the American Red Cross. [18] A news item from the Harvard Graduates Magazine of September 1917 gives his forwarding address as the Société de Crédit Suisse in Zurich. [19]

Whilst there is no actual record of what Gerlach was doing in Germany during the 1913 to 1914 period, it is curious to note that the name ‘Gerlach’ features on a photo of Alice Peroux-Williams that appeared in the Musical America journal dated May 1914, some several months before Max returned from Germany when both of them were in Berlin. [20] In light of the fact that Max was cavorting in Havana with Alice and Gibson’s son Hallam in April 1950, it seems likely that Gerlach was known to Hallam Williams and his family as early as 1913/1914, and that they had probably kept in contact throughout their lives.

Other items that appeared in the European Press during the 1913-1914 period suggest that Hallam’s mother was a popular and respected figure within the ‘American Colony’ that was ringing American Ambassador, James W. Gerard, at the US Embassy in Berlin. This is interesting in several respects as the investigation into Gerlach’s German activities performed by Harry Grunewald and the Justice Department in July 1917 reported that Max’s passport application had been secured through his personal familiarity with Major James A. Ryan, a close adviser to Ambassador Gerard in the Embassy staff. According to Grunewald’s report, Ryan was residing at the Hotel Kaiserhof in Berlin at the time that that Max secured the passport. A report compiled by the Operations of United States Relief Commission in Europe confirms that James A, Ryan was conducting his relief effort from the hotel during this period. [21] Coincidentally, records show that Gerlach and Peroux-Williams had both completed their passport applications on August 3rd, 1914 — although they appear to have travelled back to the United States separately — Alice setting out on her journey alone in March 1915 and Max with student singer/ musician, Mary L. Morrison in October 1914. [22]

In January 1914, Ambassador Gerard had been forced to issue a strong defence of the morality of American singers and musicians after an article in Musical America suggested that the women were exposing themselves to corruption and exploitation. The journal, owned by British-born American, John Christian Freund, said the girls were exposing themselves to danger by being in Berlin unchaperoned. [23] The fears that Freund was expressing may have been spurred in part by concerns over blackmailing and spying in the months leading up to the war. A spy-mania had gripped the country, and the nation responded by closing its borders and introducing super-tight regulations on those entering and those leaving the country. Gerard, a neutral envoy who was representing British interests in Germany at this time, would subsequently describe how travellers would be herded onto trains and at every port and transit point would have their particulars triple-verified by non-commissioned officers as the genheim-Polizei (secrete police) looked on. Unless one’s credentials were particularly strong you would then endure a strip-search. Every item of clothing would be held up to a strong-light so that any hidden messages sewn into the lining of the clothes would be exposed. Every bottle would be examined, every food container opened, and every suitcase, bag or portmanteau inspected for false sides, tops and bottoms. Precisely eleven separate operations would need to be completed before anyone could leave the country: several visits to the Police precinct would have to be made, questions answered, particulars checked, friends and associates called to verify your identity, and questionnaires filled-out. This would be followed by a similar procedure carried out by the Polizei-Praesidium — a series of four separate visits to seven different offices lasting the best part of a week. As Gerard explained, the method of making travel difficult had been reduced to an almost scientific formula — a process that would almost certainly have been reciprocated in America. Gerlach’s application for a passport back to the States that August must be viewed in this context.

Shortly after war in Europe had been declared, thousands of Americans, many of whom had not taken the precaution of travelling with passports, started lining up at the doors of the Embassy in Wilhelm Platz. Demand was such that even an eleven year old boy was recruited to help sort the papers. Trains were laid on to get citizens out of Berlin on a dedicated relief line that ran from Charlottenburg Station via Switzerland, Munich and Carlsbad to Holland and from Holland to England. Major Ryan had recently arrived as head of the relief and repatriation mission, taken up residency at the Kaiserhoff Hotel and it was down to Gerlach to get to know him.

When Ambassador Gerard returned to American in the first months of 1917 he co-wrote a Pulitzer Prize winning book called Inside the German Empire with the New York World’s Herbert Baynard Swope. In the book, Gerard shares his first-hand impressions of the economic, political, spiritual and military conditions that helped sustain the German nation in the first three years of the war, making special mention of the mass of bureaucratic hurdles that all Americans faced in their bid to get back home. Although Gerard and his wife had a social network that extended all over Long Island, it would it would be Swope’s parties that Scott and his wife Zelda would attend in Great Neck. It wasn’t simply Scott’s proximity to Swope in Great Neck — Scott and family on Gateway Drive and Swope on East Shore Road — that drew the pair into each other’s orbit, it was Swope’s close personal and professional relationship with Scott’s main drinking buddy, Ring Lardner. The newspaperman also had a deep, abiding friendship with Gerlach’s Speakeasy patron, Arnold Rothstein and his wife Carolyn. At around the time that Max was managing Rothstein’s speakeasy at No. 51 West 58th Street, Swope was renting a city apartment at No. 135, and Rothstein was living in one at No. 145 West 58th Street. That’s how cosy the pair had become. [24]

Although divorced some several years, Alice and Gibson Williams would both provide talks on the ‘truth’ of the situation in Europe on their occasional trips back to the United States. In February 1915, Musical America reported that Alice was now striving to bring about an amicable understanding between America and Germany “by deeds rather than words”. As a celebration of this special relationship she would be joining the famous German baritone Paul Knüpfer at the Beethoven Hall, a performance she hoped would represent a “veritable entente cordiale”. [25] A little earlier in February 1915, Alice had sung at a benefit concert organized by Mrs Hans von Bülow. [26] Bülow, a virtuoso pianist and conductor, had been instrumental in popularizing the composter Richard Wagner, whose autograph Gerlach possessed and which he claimed had been handed to either his father or his grandfather when the family were still living in Germany. [27]

It’s more that he was a German Spy During the War

Fitzgerald placed no small amount of emphasis on rumours of spying in the Gatsby novel. At Gatsby’s parties, guests exchange furtive, short-breathed rumours about his possible wartime adventures. In dramatic terms, it was the verbal equivalent of puffing out a toxic cloud of smoke and asking his readers to pick shapes from it. Some say that Gatsby spied for Germany during the war and some say that he’d killed a man once. Others, who claim to have known him growing up in Germany, insist that he is either a cousin of Kaiser Wilhelm or a nephew of Paul von Hindenberg, the former General of the German army who was poised to become President at the time the novel was published. There’s no denying that Gerlach himself had done much to contribute to the various rumours flying around about his loyalties during the war. When agents acting on behalf of the American Protective League spoke to his character witness, George Young Bauchle, Bauchle claimed that Gerlach had once shown him a signed-photo of composer Richard Wagner, possibly the most iconic symbol of German Nationalism outside Adolf Hitler. Gerlach alleged that the picture had been signed personally by Wagner for his father, Ferdinand von Gerlach, when he was acting as secretary in the Secret Chancellery of Frederick III. In Imperial Russia, the Emperor’s ‘secret chancellery’ — or the Geheimer Kanzlei as Kruse describes it — was a dreaded organization consisting of spies and spy handlers, men and women who would have the unenviable task of keeping tabs on royal subjects. The combination of Wagner and Privy Councils makes it all sound tantalisingly Machiavellian and full of fabulous intrigue, but maybe the House of Hohenzollern was very different to that of the Romanovs. The notion that Gerlach’s father was some glamourous ‘master spy’ is an attractive one, but there is no firm evidence to support it.

It wasn’t the last time that Max would reaffirm his roots to Imperial Germany. When approached by a reporter during a flight at Westfield International Airport in April 1930, Gerlach would present himself as a “former German Royalist”. [28] Rumours of German spies were rife during the war. Not even the singers and musicians that Max was associating with in Berlin and Manhattan were immune. A report in Musical America in June 1917 spelled out the scale of the problem the singers were facing, Dr O.P. Jacob writing that that he had been struck “by the persistency with which the rumour, ever and anon, crops up that many German artists, opera singers by preference, are nothing less than German ex-officio, secret service agents.” [29]

The rumours of spies operating beneath the veil of opera and musical theatre had arrived the same month as Agent Harry Grunewald and the Bureau of Investigation started compiling their report on Gerlach. His friends and associates on the Berlin music scene, like Mary L. Morrison and Alice-Peroux Williams, can’t have failed to trigger some general interest, but equally, it may well have been prompted by something more specific. Sure enough, the report, which Grunewald completed on June 29, 1917, just happened to coincide with news that leading New York Opera singer, Edyth Wilson, was presently on a tour of Berlin, Munich and neutral territories like Holland, pushing a peaceful, if pronounced, pro-German message. The news chimed with the previous efforts of Alice-Peroux Williams and Paul Knüpfer to bring about an amicable understanding between America and Germany “by deeds rather than words”. The idea of an “entente cordiale” might have seemed harmless enough when America was taking a neutral stance in the war, but the sentiment would have been deemed undesirably unpatriotic as the US started mobilizing its troops against Germany in May 1917.

The man accompanying Edyth Wilson on the tour was her musical director, Herr von Gerlach. A report in Musical Courier in February 1917 revealed that Wilson would be among several stars from Berlin and Munich who were scheduled to give a performance at The Hague under the direction of Intendant von Gerlach. [30] The concert, curiously enough, was based around the work of Wagner, the composer that Wilson had become most famous for popularising in America and Europe. Contrary to what you might think, ‘Intendant von Gerlach’ appears not to have been Max Gerlach. The Intendant was Berlin-born Arthur von Gerlach, an Opera House aficionado who was lending his support to the German Foreign Office in their diplomatic efforts with America and the neutral territories. Nevertheless, word might have gone around that the pair were related.

There are several questions worth asking: was it possible that Max Gerlach was trading on some alleged (or real) family association with Arthur von Gerlach during his musical time in Berlin? Had Max inveigled his way into the operatic circles at the Embassy with the intention of gaining monetarily from these contacts, for the purpose of intelligence gathering? Was it in Berlin that he had got the autograph of Wagner and not, as not as he told Bauchle, as an heirloom from his father when he was in the service of Friedrich III?

14 Jones Street. Max Attempts Suicide

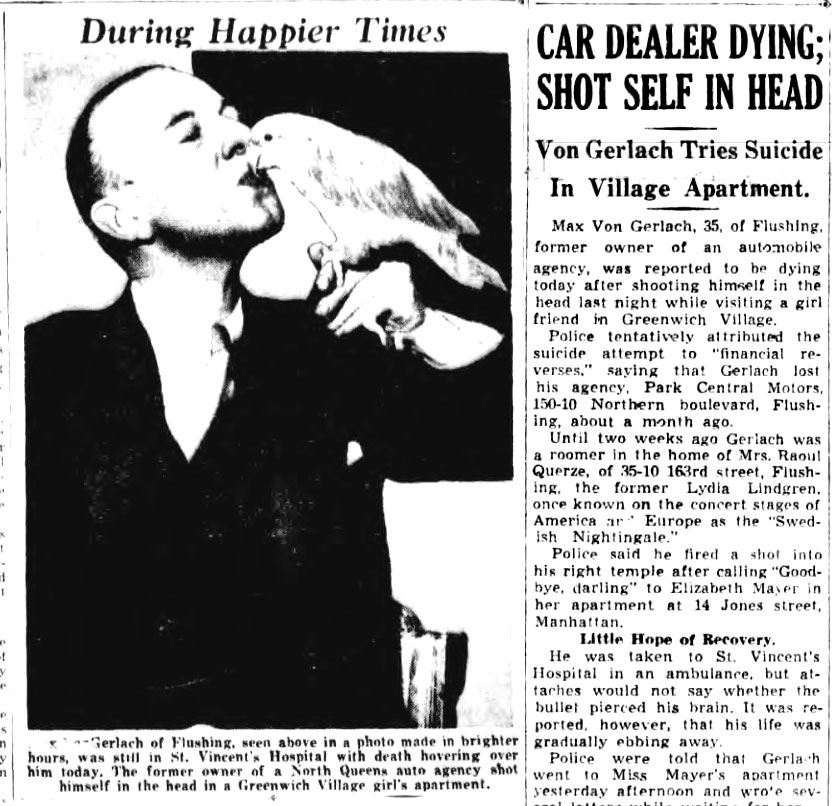

News of Gerlach’s links with the world of opera would continue well into the 1930s when it was reported by the press of New York that Max had been living at the $40,000 mansion of former singing star, Lydia Lindgren in Flushing. The story they told was a strange one. In the last week of December 1939, some ten weeks after war had been declared in Europe, a 55 year old Max Gerlach sat in the apartment of his friend, Elizabeth Mayer in Manhattan, put a revolver to his head and pulled the trigger. Although the newspapers speculated that Max had been plagued by the collapse of some business concerns, they were also keen to point out that just a few weeks prior to the incident, Max had been living at the home of former ‘Swedish Nightingale’, Lydia Lindgren at 35-10 16rd Street in Flushing. [31] Like Gerlach, the American-based singer who could speak five languages and included the likes of Nietzsche and Goethe among her favourite reads, had spent time studying music in Berlin. [32] Her meteoric rise to stardom had been helped by her romantic association with German-American millionaire, Otto H. Kahn — chairman of the Metropolitan Opera Company and a powerful figure on Wall Street. In the early 1920s she had married Italian tenor and voice coach, Raoul Querze.

At the time of the Max’s attempted suicide, the 55 year-old Lindgren had been out of the newspaper headlines for some seven years or more. In the 1920s and early 1930s the startlingly beautiful soprano singer had featured in a steady, glamourous stream of diva sensations, mysterious disappearances and high-profile sex scandals. But in the six years leading up the incident, things had all been relatively quiet. The only exception to this was a story printed in the last week of October, just a matter of weeks before Gerlach pulled the trigger. According to the story, Lydia was seeking to petition her former husband, Raoul Querze, for the provision of a temporary allowance. In her customary dramatic fashion, the singer had claimed that the $300,000 fortune she had earned originally, had finally been exhausted. [33] It is not known if Gerlach and Lindgren had been having an affair, nor if his suicide attempt at the home of Mayer had in some way been wound-up with the singer’s own declining fortunes. According to a full page spread in May 1950, Lindgren had been left destitute. The $40, 000 mansion in Flushing that she shared with Gerlach was heavily mortgaged and the tax-burden on all her valuables, including her jewellery had been sold. She dismissed the few furnishings she had left in the house as ‘junk’. [34]

As Gerlach dragged his feet around Washington Square Park on the afternoon of December 21st, it would have been perilous underfoot. It was the first day of winter. Ice had brought traffic to a standstill and the roads around the main streets would have been peppered with sand. The temperatures looked set to plummet even further that afternoon, as another barrage of snow showers moved in. It was going to be a White Christmas. Three more shopping days to go. But poor old Max wasn’t thinking that far ahead. Gerlach appears to have let himself into Mayer’s apartment at 14 Jones Street the afternoon prior to the incident and spent the subsequent time writing letters as he waited for her return. The pair had sat reading until 10.00pm when Elizabeth looked up to see him put a revolver to his head, whisper very calmly his last goodbye and fire a single shot into his right temple. Police would find four sealed letters in his pockets. Who the letters were addressed to and what were included in them was never disclosed.

Mayer appears to have known as much about Max as the rest of us. As far as she was aware, Max von Gerlach was a retired army officer and former German baron. Describing him to the press echoed Scott’s description of Gatsby: he had an immaculate military bearing and a strong Oxford accent. Beyond that, she knew very little about him. [35] When quizzed about Baron von Gerlach, the German Consulate in Manhattan said they had no record of any baron by that name. Lydia Lindgren claimed that she too had no idea about Gerlach’s background, only that he had left the house rather suddenly and had neglected to take his things. Police told reporters that Gerlach was not given to talking about his past, his relatives or personal affairs, and as a result they had practically no further information on him. Just days earlier, a real German Baron was confronted with a no less violent tragedy when the 21-year old mistress of Baron Friedrich von Oppenheim, a wealthy German monarchist, plunged to her death from his 10th floor apartment in Lower Manhattan. The woman, Lola Lazlo, was the stepdaughter of Hungarian film director, Aladar Laszlo. Friends of the girl were adamant that Lola was incapable of taking her own life and the Baron was grilled by Police. [36] At the time that of the tragedy the Nazi Party were pressing for the Baron’s return. Pressure was being heaped on his wife back in Cologne, but according to his family, von Oppenheim was reluctant to leave America and provide his backing to a war that he and his conservative nationalist circle of friends believed to be ill-judged. With the prospect of his assets being seized and the safety of his wife and children now in jeopardy, he returned some eight weeks later. In 1942 he would be investigated by the Gestapo for assisting in the evacuation of Jews workers from the Netherlands.

Little or nothing is known about Elizabeth Mayer, the woman that Max was staying with at the time of his attempted suicide, although the address of the apartment, 14 Jones Street in Greenwich Village, does make it possible to get a snapshot of Max’s lifestyle and the company that he kept at this time. For the best part of twenty years this fashionable Manhattan district was the heartland of New York Bohemia and in 1939 it was literally teeming with boisterous Marxist radicals, bearded artists, freethinkers — and Soviet spies. According to a report drawn up by the Special Committee on Un-American Activities, 14 Jones Street was home to no less than three card-carrying members of America’s Communist Party that year: Mary Gutchess, Clarence Dorman and Silas Goodwin. If you were to look at the street as a whole you would find that a total of sixteen party members made up the tiny Manhattan block, composed of around thirty separate buildings. [37] At nearby 18 Gay Street were Communist Party members Frances Kline and Mary McCarthy, the Trotskyist author girlfriend of Scott’s longtime friend and confidante, Edmund Wilson. Mary’s neighbours at 17 Gay Street would eventually come to the attention of Federal Agents when it was learned that a Soviet GRU Cell was operating from its premises. The Soviet painter and spy, Esther Chambers was a regular visitor to this address too, and another good friend of Wilson and McCarthy. In later years, Chambers would famously would describe how this tiny little apartment on a curvy block-long street was used as the secret base for a highly efficient communications system between the Communist underground in America and their counterparts in Germany. Letters and film would be carried by couriers using the North German Lloyd SS Line and the Hamburg American Line, developed in-house from a makeshift dark-room consisting of a short-tub, a shelf and battered old photographic enlarger, that had been squeezed in an almost impossible position beside a basin and toilet in the closet-like Gay Street bathroom. Once the film had been developed, couriers and Comintern agents would then meet up in clubs and cafes dotted around the Village and perform a crepuscular routine of ‘dead-drops’. [38] According to the passionate anti-Communist crusader Kenneth Goff, foreign agents would hand Chambers and his friends money belts containing as much as $10,000. The money would then be used promoting the revolution in South America, the Philippines and Japan. On other occasions Chambers would fly to San Francisco and to the Soviet colony in Hollywood and disperse funds there. [39]

Radical Greenwich

John Dos Passos (a prominent supporter of Leon Trotsky during the 1930 show trials) and Edmund Wilson were just two of Scott’s friends who had been cool, contented residents of ‘The Village’. At 3 Washington Square North, the pair would have once been just a five-minute walk from Max’s flat at 14 Jones Street. Even closer to Max on McDougall Street was the passionately subversive, Washington Square Bookshop, one of the first book stores ever to stock the banned and ‘obscene’ Ulysses by James Joyce. The Village was about as extreme and as visionary as it got. The story being told in the press was that it had become something of a legend among “long haired poets” and artists. But this wasn’t a new phenomenon by any means. In the early 1920s, the district had been home to Jane Heap and Margaret C. Anderson’s censor-defying Little Review, before it had no option but to move to Paris. Just a few doors down from this was Samuel Roth’s porn and ‘banned-book’ emporium, The Poetry Bookshop. It was here that the more discerning customer could get their sweaty little hands on ‘bootleg’ copies of Ulysses by James Joyce and Theordore Dreiser’s Genius, invariably dispensed without the slightest shame in their beguiling brown-paper bags. The district famous for its radical art and politics was also home to one of the most radical Jazz Clubs of its generation too. Ten minutes’ walk around the corner from Max and Mayer at 14 Jones Street was Barney Josephson’s hot new venue, Café Society. The club at Sheridan Square, would be the first racially integrated nightclub in New York. Josephson, a former Cotton Club regular had launched the club just 12 months prior to Max’s suicide attempt, its name handed to given to him by Igor Cassini’s ‘Cholly Knickerbocker’ predecessor, Maury Paul, who dutifully promoted it as the ‘the Wrong Place for the Right People’. [40]

Josephson had originally been inspired by the clubs he had visited in Montmartre in Paris and in Berlin in the early 1930s. It was in Berlin that he had become utterly mesmerized by the reactionary political forces gathering in force around its bars. The bars would be tiny things with small stages. Singers and musicians would be boxed-up and eye to eye with artists, caricaturists, composers, poets and left-wing intellectuals. It was the ultimate in anything goes, from nude dancing to erotic performances, gay acts, drag acts, drug acts and everything in between. Josephson found the experience totally exhilarating and soaked it up. The smoky burlesque atmosphere of the club also packed a clear anti-fascist message. Once the doorman had shown you in and ushered you downstairs you would be met by the Hitler Monkey — a large clay sculpture of a monkey with the Fuhrer’s head dangling from a pipe on the stairwell. Just three years earlier, Barney’s brother Leon had been among thirty people arrested for plotting Adolph’s murder. A short time later, George Mink — duly charged alongside Leon that day — would be revealed as one of Stalin’s star assassins — a special agent in the G.P.U whose real priority was German naval plans. It was a world turned upside down. On the walls would be murals satirising their upper-crust Broadway rivals. Behind the bar was a mural of animals. A long, linear menagerie of walruses, bears, pigs, orangutans, lizards and dogs would provide a surrealist mirror of a noisy clientele hollering for drinks in front of them. A cigarette girl would drag her wares around the tables, and following her an ‘ashes girl’. In March 1939 an ad appeared in Scott’s old campus paper, The Daily Princetonian: ‘Café Society: 2 Sheridan Square, Chelsea 2-2737 — Don’t miss, “What You Going to Do When There Ain’t No Swine” sung by Billie Holliday.’

Just four weeks before Max tramped up through the snow and let himself at 14 Jones Street, the unthinkable had happened — Kristallnacht, the Night of the Broken Glass. Brutal Nazi groups had launched a series furious assaults on German Jews. People were beaten, shops were looted, properties were burned and a brand new spectacle of hell spread like wildfire across the nation. When the SS Bremen docked at one of the nearby piers in the Village, a scuffle broke out between Nazi-sailors and outraged New York dockers. The atmosphere of holiday carnival at the club took on a peculiar, manic aspect, the tootin’ of the trumpets and the boogie-woogie licks mingling in a way that only Jazz ever could with the schizophrenic mood of the city.

Like so many of the club’s neighbours on Jones Street, the owner’s brother, Leon Josephson would eventually be subpoenaed by the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Federal attention would also fall on its musical director, the civil rights activist and former aristocrat, John Hammond. Fast-forward to the early 1960s and Hammond, still intent on breaking down cultural barriers would play a critical role in launching the career of folk-singer, Bob Dylan. The cover for his second studio album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan was in fact shot just outside 14 Jones Street. All in all, 14 Jones Street was probably the last place on earth to find a preposterously affectatious German monarchist holding a gun to his temple.

Elizabeth Mayer

Nothing at all is known about Gerlach’s girlfriend, Elizabeth Mayer, but a small ad run in Edmund Wilson’s Marxist-lite journal, the New Republic, might just offer a clue. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the journal regularly promoted rooms here: “Greenwich Village, 14 Jones Street, near Sheridan Square. Two separate rooms, automatic refrigerator, incinerator, fireplace, $60 to $90. References. Agent on premises.” [41] The property itself was a five-storey building made up of around a dozen or so apartments. In years gone by the block had played a key role in New York’s ‘settlement’ program. Musician and translator, Elizabeth (Wolff) Mayer, who fled from Germany to New York in 1936, had worked on several contributions to New Republic and it is possible, given the journal’s popularity with journalists, authors and editors, that the owner of the two rooms, who also lived on the premises, may have been keen to let it out to likeminded souls in arts and publishing. The theory has other supporting elements. Scott’s close friend Edmund Wilson, who appears to have used a similar caricature of Gerlach in his 1924 play, The Crime in the Whistler Room, was associate editor of the New Republic on an on-off basis from the mid-1920s to the 1940s. Perhaps aware of the room’s existence, he had mentioned it to Mayer and Mayer had taken it on, or Mayer had mentioned it to Max and Max had taken it on.

In the summer and autumn of 1961, 14 Jones Street was the home of future Assistant Secretary of State, Richard Holbrooke. Still in his early twenties, Holbrooke was an occasional student writer for the New York Times. At this time, Greenwich Village was still very much the refuge of unknown artists and radical thinkers. Jazz may now have taken a backseat to Rock n’ Roll, but the quick-witted snarl of folk flicked the Vs at the the establishment in the same casual and prickly melodious way. Holbroke’s one room, ground floor apartment was shared with Lawrence Chase, the editor of his college newspaper. When Holbrooke was offered an advisory role at the White House during the Johnson administration, the FBI performed the usual background checks. During the course of their investigations they found that the youngster’s name was included in the records of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee at Brown University. This would be the 1959 to 1961 period, in the run-up to the Bay of Pigs. Until it was disbanded in the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination, the Cuba Committee was believed to have served as Fidel Castro’s propaganda arm in the United States. It was during this same period that Holbrooke began spending much of his time at the home of David Rusk whose father, Dean Rusk was serving as President Kennedy’s Secretary of State. It was in fact Rusk who would guide the beleaguered President through the Bay of Pigs fiasco that same year. [42] Although concerned about what they had found, the FBI found no tangible evidence of espionage.

It is interesting to note that it was the same Elizabeth (Wolff) Mayer who was a one-time romantic interest of the poet W.H. Auden. Auden, also a friend of Wilson and a contributor to New Republic, moved to New York the very same year that Max attempted suicide. The address that Auden provided on the ship manifest in January 1939 was that of Random House founder, Bennett Cerf. Like Wilson, Cerf was another prominent figure in the anti-censorship movement then energizing the left-wing cliques and stormy petrels of Lower Manhattan. British Intelligence would open their own file on Auden in the 1930s and years later the poet would be suspected of playing a part in the escape of Cambridge Spies, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean. Auden would eventually settle at 7 Cornelia Street in Greenwich Village, a property that was practically back to back with 14 Jones Street. During the early phase of his arrival Auden was reliant on Mayer for emotional and artistic support. Her ‘open house’ on Long Island functioned like some Parisian salon, a refuge for any artist, singer or musician looking to recharge their creative batteries on the constant flow of energies buzzing about the home. There is, however, no record of Auden’s patroness, Elizabeth (Wolff) Mayer having a separate apartment in Manhattan to the house she had on Long Island. Despite this, she remains a credible, if not totally satisfactory suspect in our search for Gerlach’s girlfriend. A trawl through the US census of 1940 reveals that by April 1940 Mayer was no longer using the Jones Street address. Research undertaken by Horst Kruse in 2014 suggests that Max himself had little option but to move on: the bullet that had entered his temple had left him blind. Six months after his attempted suicide, Max could be found among the 36 inmates residing at the State Blind Asylum. [43]

Max and Mizener

When Gerlach arrived in Havana with Hallam Keep Williams in April 1950, Cholly Knickerbocker had made a point of observing that Baron von Gerlach, who was going to write a book about his life was now ‘blind’. The way that Cassini phrases it, however, suggests that Gerlach’s real-life adventures had been every bit as sensational as the spy and bootlegging rumours that swirled around Scott’s hero: “The eccentric Hallam Keep Williams has just arrived in Havana with Baron Max von Gerlach, who is the protagonist of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s ‘The Great Gatsby’. Hal says he is going to write a book about the Baron, who is blind now, that will top Fitzgerald’s famed work.” Given the scope for criminal prosecution, one might speculate that the book, were it ever to be written, would be more likely focus on Max’s many experiences among the fantastically rich and talented denizens of New York than his bootlegging exploits with Arnold Rothstein. Lifting the lid on his time in Berlin and on his on-off romance with opera was one thing. Revealing the inner workings of organised crime was another. It would have come with considerable risks to his safety.

In February 1951 Gerlach made the first of many attempts to contact Fitzgerald’s biographer, Arthur Mizener. Max, now 65, was desperately keen to talk to him about Gatsby, and Mizener seems just as desperately keen to avoid him. Horst Kruse has done an excellent job of summarizing the scene: Gerlach hears Mizener talking on the Mary Margaret McBride radio show about his new, groundbreaking biography of Scott. Minutes later, Gerlach contacts the radio station telling them that he is “the real Jay Gatsby”. A secretary working at the station approaches Mizener and informs him of the call. The pair exchange a series of letters, and Mizener, who has already mentioned “a Teutonic-featured man named von Guerlach” in a footnote in his book already, seems determined to avoid a meeting. As far as Mizener is concerned, Scott may have taken some inspiration for the Gatsby character and some superficial characteristics of Gerlach, but the things that really define Jay Gatsby — like his “motives” and “ideas” — were not those of Max. Mizener suggests that Gerlach puts down everything he knows in writing, but Max is reluctant to do this. As much as he would like to share the evidence that would back it up, he would prefer not to put it in writing. Frustrated by the obstacles being put in his way, Max shares his disappointment. Responding to Mizener’s letter, he describes the scholar’s rather dismissive assessment of the role he had played in the creation of Gatsby as purely “speculative”. In a letter dated July 2, 1951 Gerlach suggests they communicate via “through other channels”, before mysteriously adding: “I would prefer it this way as there are few people to whom I could express my candid comments with regard to F. Scott Fitzgerald, who might not, perhaps, misinterpret them”. [44] Kruse asks a very reasonable question in his book: why, after going to all that trouble to mention Max’s name in his book, was Mizener able dismiss his tale so casually? And why didn’t he want to meet him? You have to try and understand how Max might have felt at the time; on the one hand Mizener had mentioned him to others as possible source for Gatsby, and on the other he seemed curiously keen to reject the idea outright when approached by the man himself. What was undoubtedly curious from Gerlach’s perspective, was that Mizener now had little or no curiosity at all.

Mizener appears to have first learned about Gerlach through conversations that Princeton scholar, Henry Dan Piper had with Scott’s wife, Zelda Fitzgerald, shortly before her death in a hospital fire in March 1948. The story told by Zelda’s biographer Nancy Mitford (another one time Princeton scholar) is that that Piper had visited Zelda in a fairly spontaneous fashion at her home in Alabama in March 1947, just as he was being discharged from the army at the nearby Anniston camp. What Mitford says, however, isn’t strictly true. By the time that Piper was interviewing Zelda, he had already taken up his position within the Graduate School at Princeton. A local news item dated November 1945 suggests that Piper had already received his discharge and had made the rather surprising transition from Princeton’s Department of Chemistry, where he graduated in 1939, to the Department of English. [45] During the war Piper had worked on the highly classified Manhattan Project, the research and development program headed by Robert Oppenheimer, that would culminate with the world’s first atomic bomb. The work that Oppenheimer and his team produced would result in the complete annihilation of the cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki — and sealed the end of the Second World War.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, Piper, who had provided problem solving support to the head of research on the Manhattan Project, exchanged his lab coat for the neat pair of slacks and corduroy jackets that were common among the tutors at Princeton’s literature department — the emotional fallout of the bombs perhaps having no small amount of impact on the path that his post-war career would take. Mitford writes that Piper had been greatly intrigued by Fitzgerald’s work whilst writing for the Princeton magazine as an undergrad. In the frightening new world he had partly created himself, the simple pleasures of Piper’s youth must have shone like light at the end of a very dark tunnel. Whilst science could so easily destroy the world, art could so easily save it. Sometime between March 13 and March 14 Zelda invited Piper across for tea, during which he told her of his great admiration for Scott and his plans for writing his biography. The conversations went well, and although still emotionally and mentally drained from her regular trips to the Highland View sanatorium for treatment for schizophrenia, Zelda was relaxed and lucid enough to talk about her and Scott’s life together. It was only when Piper told her that he had been given access to papers and letters the possession of Scott’s attorney Judge John Biggs Jnr that things became a little more tense. [46] Within minutes of mentioning the papers, Zelda seemed shaken. She needed to lie down. The chat, for now at least, was over. When he arrived the following day Zelda was wringing her hands and seemed visibly distressed. Piper recalled that all the old energy and confidence that had radiated from her the previous day had been lost.

On November 2, Zelda returned to Highland Hospital for further treatment. Before stepping into the taxi she went and hugged her mother and told her that she was not afraid to die. At midnight on March 10th a fire broke out on the floor where Zelda was sleeping. She had several other patients, each of whom had been given strong sedatives to help them sleep, were among the nine fatalities as the fire swept from the kitchen, up through a dumbwaiter shaft to the very top floor of the building. One month after a coroner’s inquest returned a verdict of an accidental fire, 44-year old Willie Mae Hall, night supervisor at the institution, claimed responsibility not only for the fire but for over sedating patients. At nine o’clock on April 13, Hall walked into the city police department, demanding that officers lock her up immediately, clearly terrified of what might happen next. [47]

The gossip that Zelda shared about a “Teutonic featured man” called “Guerlach” was never actually published in Piper’s eventual biography of Scott in 1965. Instead Piper appears to have handed the information to Mizener, who featured it as a footnote in The Far Side of Paradise in 1951. Exactly when Piper had handed his notes to Mizener isn’t known. Mizener appears to have started his biography of Scott in 1945 but the inclusion of the detail only in the endnotes of the book suggests it may only have been shared with Mizener shortly before going to print. This is a possible explanation for why it didn’t appear in the main body of the text. Either way, if Piper had first learned about the identity of Gerlach from Zelda as he claimed, then Zelda was no longer alive to corroborate his story. The huge revival in interest in Scott triggered by the production and release of Paramount’s 1949 Gatsby remake would have to pass by without comment from the one person who knew Scott — and perhaps Gatsby and ‘Guerlach’ best — Zelda Fitzgerald. [48]

Gerlach’s Ghost Writer — Hallam Keep Williams

What, if anything, became of the book that Gerlach had intended to write with Hallam Keep Williams in April 1950 isn’t known. Journalist Joe Nocera thought him worthy of investigation. Sadly our knowledge of Williams turned out to be little better than our knowledge of Gerlach. Looking at their both lives is like looking through frosted glass; you can make out the vague, blurry outline of things, things you think you see, but these things are so lacking in definition, so full of gaps in our understanding that they have all substance of ghosts. The whole thing is like looking at some fascinating antique tapestry where it is the holes and not the fabric that dominates. What we know about Williams can be summed up fairly quickly and some of which has been touched on already. Hallam was born on April 14, 1907 to Alice and Gibson Tenney Williams, the former a respected opera singer and the latter a prominent broker from a wealthy and respected family in Buffalo, New York. [49] Hallam’s Uncle, Charles Hallam Keep was the former US Secretary of State during the Roosevelt and Taft administration and Hallam and his siblings would be embroiled in claims over his estate for the best part of fifty years. [50] In 1910 his parents separated and in March 1914 the marriage was dissolved. It was around this time that Hallam left with his mother and siblings for Germany. During the war and post war years, Hallam’s education is believed to have been “received and polished” in Budapest, Vienna and Petrograd in Russia. [51] From 1909 he was living in Berlin, and during the late 1920s had joined his mother in the concert halls of Paris, playing the Ukelele and singing in several different keys and languages as vaudeville act, ‘Bubbles’ Williams. [52]

An item in the Paris edition of the Herald Tribune in June 1928 describes Hallam as ‘jazzing’ his way through music halls and salons attended by European kings, queens and nobility with the stage-act, The Happy Trio, a group that comprised Hallam, the Oxford-Harvard educated Billy Walker and the young, black jazz musician Gene Ramey. Hallam is described in the report as a former ‘vaude entertainer’ and radio and recording artist. By 1928 the group were appearing nightly in the grill room of the Chez Paul & Paul on Paris Right Bank (champagne not obligatory). The teenage trio appear to have first found fame in New York. Hallam’s manager at this time was Jim Carroll, the brother of producer and Broadway band leader, Earl Carroll. [53] In 1926 Earl found himself in jail after bringing out a nude young woman reclining in a bath of illegal liquor at a party thrown at his theatre on Seventh Avenue. One of Carroll’s ‘Vanities’ stars was the former ‘Follies’ showgirl, Peggy Hopkins Joyce — sometime lover of Arnold Rothstein.

It was during his time in Paris that Williams is believed to have met Ann Murdock, the beautiful millionaire actress whose marriage to Wall Street banker, Harry C. Powers had ended in divorce some years before. According to press reports it was a whirlwind romance and the couple married in August 1928 in Rye, New York. The word going round was that the handsome blond lothario with boyish curly locks had come back to New York with dreams of being a music agent. Within a month of the marriage, Murdock had become seriously ill and the relationship faltered. As Murdock convalesced in a New York sanatorium, Hallam, a serial philanderer with no fixed job or abode, met and romanced Ruth Anderson, a rival actress. As media speculation intensified about the couple, Hallam made his escape to Paris and it was here that he met the Mexico-born Byron Khun de Prorok. Another fraudulent Baron, Prorok had somehow blagged his way into the Adventurers Club of New York and onto some bizarre archaeological dig in Africa. According to the press of New York, Hallam would be going with him.

In 1929 Murdock filed for divorce and Hallam continued his romance with former ‘Vanities beauty’, Ruth Anderson. [54] For several months he had been in Nice where he had continued to perform as multi-lingual ‘uke’ player, Gayne ‘Bubbles’ Hallam. [55] After this he was back in New York. The details that Williams provides on a ship manifest in 1929 show him sharing rooms at 120 West 58th Street in New York with journalist Heywood Broun, a close friend of Ring Lardner, Harold Swope and several other Algonquin Round Table regulars that Scott and Zelda used to party with back in Great Neck. [56] Scribners editor Max Perkins mentions Broun in a letter he scribbled off to Scott whilst the author was working on Gatsby in France. Max was telling the author that he had found a new place in New Canaan and Broun was among the most hospitable of his neighbours. His invites across for supper were about as close as he got to parties, Perkins jokes. [57]

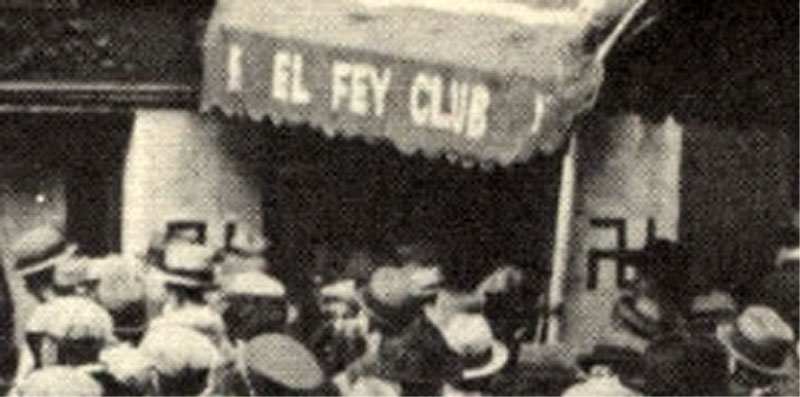

The detail about Hallam and Broun’s apartment is interesting for several reasons: the apartment was just around the corner from Max Gerlach’s speakeasy at 132 West 58th Street and there is some indication that Broun was on very friendly terms with a mutual acquaintance of the pair called Texas Guinan — the notorious actress and Speakeasy hostess who provided glamourous front-of-house entertainment for gangster Larry Fay and Owney Madden at their El Fey nightclub on West 47th Street. The former actress had, like Gerlach, been schooled in the art of running speakeasies by Arnold Rothstein, the man who is believed to have provided the initial capital for the club. In what might be an intriguing coincidence, it is interesting to learn that that club had two large swastikas on either side of its door. It is something that may have an echo in Gatsby. As the novel’s narrator Nick Carraway pushes open the door to Meyer Wolfshiem’s New York office, it is marked by a sign reading ‘The Swastika Holding Company’.[58] When Nick enters the office he hears someone whistling the popular Catholic opera-tune, The Rosary. Rothstein’s partners in the El Fey, Larry Fay and Owney Madden, were of Irish-Catholic heritage, and it is not beyond the realms of possibility that Scott was alluding to the pair’s partnership with Rothstein (Wolfshiem) in the club and was using the swastika motif as a nod and wink to amuse fellow regulars like his friend, Edmund Wilson. [59] The swastika also appeared on the cars in Fay and Hallam’s taxi-firm: one on the driver’s door, one on the passenger door and one on each of the four hubs of the wheels.

A report in New York’s Daily News in August 1930 would describe how Hallam had been hired by Fay as a $50 a week taxi-cab salesman. It also describes how Hallam’s friend, Tex Guinan had once taken him aside to reveal the true age of his wife, Ann Murdock and advised that he should curb his spending habits. [60] It is alleged that Fay’s entry into the nightclub business had been bankrolled by Gerlach’s old boss, Arnold Rothstein. Guinan, who was roughly the same age as Max, would die in 1933. One of the pallbearers at her funeral was Hallam’s flat-mate, Heywood Broun. Scott’s friend Edmund Wilson would famously describe her as a formidable, glittering woman operating under the “great glowing peony” of a ceiling that melted from pink to deep rose. To woozy, beguiled patrons like Wilson there was something coarsely hypnotic about her.

The Hostess and the Kaiser

Interestingly, there are indications that Guinan was in Berlin at roughly the same time as Max Gerlach. Like Hallam Keep William’s mother, Alice, Guinan had begun her career as a soprano singer with a New York Opera company. Taking a break from a ‘Whirl of the World’ concert tour Guinan had made the trip to Germany. It was in here, according to an interview she gave to the press 1915, that Texas received the personal attention of Kaiser Wilhelm. In a short, teasing interview with the Seattle Star, Guinan described the scene. She had been sitting alone on a bench under a linden tree enjoying a book when several German officers passed by. Suddenly there was commotion. A battalion of infantry were marching through the street, and when some overzealous officers, keen to subdue subversive characters, started mingling amongst the crowd. As Guinan stood to observe the procession, the burly hand of an officer who was “shouting in vigorous German” gripped her by the arm and pushed her backwards. Guina’s spontaneous cries of injury attracted the attention of the Kaiser who quickly moved forward to help. The reason for his intervention, Guinan tells us, is that he discerned that she was American. He then explained how much he would like to visit America. [61] In all fairness, Guinan’s story was a typical piece of pro-German propaganda at time a when many American newspapers were reflecting public fears about imminent war with Germany. Either way, if any part of the story is true then the incident places Texas Guinan in Berlin in 1913, the same year that Max Gerlach and Hallam’s mother, Alice Peroux-Williams were in also Berlin.

Hallam’s marriage to Ruth Anderson appears to have lasted little longer than his marriage to Murdock. By 1931 the couple were in the throes of a very public divorce and for the next fifteen years Hallam disappeared from the headlines — the only notable related events in his life being the murder of his cab-boss, Larry Fay in January 1933 and the no-less sudden death of their mutual friend Texas Guinan in November that same year. In the immediate aftermath of Arnold Rothstein’s murder in November 1928, a number of better known establishments were raided by Police, including those being managed by Guinan. The hostess would share her memories of this and her old friend, Arnold Rothstein in a book she planned to publish called ‘Hello Sucker’. [62] In July 1930, the publisher Alfred A. Knopf signed a contract with Carl van Vechten — a friend of Scott — for his novel Parties, a book that depicted the wild and sensational antics of Americas boundary-breaking club lovers. Pictured witnessing van Vechten’s signature was Texas Guinan — Queen of all parties. [63]

Among those who served as models for von Vechten’s novel were Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald who appear in the book as David and Rilda Westlake. The Parties author had been introduced to Scott when he first arrived in Great Neck in October 1922 and the group partied regularly until Scott’s last-minute departure in May 1924. [64] Von Vechten’s publisher, Alfred A. Knopf would, incidentally, go on to publish the second edition of Arthur Mizener’s groundbreaking biography of Scott, The Far Side of Paradise (1951). It was this book that featured the first ever public mention of Gerlach as a source for Gatsby. In May 1925, van Vechten reviewed The Great Gatsby for The Nation, hitting the nail right on the head when he wrote: “The theme of a rather soiled or cheap personality, transfigured and rendered pathetically appealing through the possession of passionate idealism.” His diary entries in 1923 also reveal that he attended the gatherings of the Algonquin Round Table with Hallam K. William’s 1929 ‘roommate’ Heywood Broun and their mutual friend, Texas Guinan. [65] There is no record of Guinan ever publishing ‘Hello Sucker’, but one wonders that if it had, it may well have been published by Knopf. Shortly before her death the last of her legendary speakeasies was firebombed and Texas returned to the stage in America, having already been denied to entry to England and France. Headlines like ‘Actress Silenced By Death’ duly followed.

The next press reports of the 37-year old Hallam have him hooking up with twenty-one year old glamour star, Josi Johnston. Like Hallam’s first wife Murdock, Josi was heir to a million dollar fortune and had fallen heads over heels in love with him. Against their parent’s wishes, the two Stork Club regulars married on August 1st 1944. The venue they choose for the wedding was the University Chapel at Princeton. The reason why they chose Princeton to tie the knot remains unknown. There is certainly no indication that either of party was enrolled at the university, so it may have been at the suggestion of an unknown third-party. Either way, it’s extraordinary to find a friend of Gerlach’s so close to the Ivy League college that produced Fitzgerald. The romance lasted barely 18 months, and despite the birth of their child, Turner, the couple divorced. [66] Two years later Williams married Ann Baldwin. After starting and aborting a film production company, Hallam tried his hand at writing dramas: Façade (a three-act play with wife, Ann Baldwin in 1946), Alimony Pete (a three-act play in 1949) and What Happened Then?/This Is Why I Pray (musical compositions with John Vroman, 1961). [67] It is April 1950 when Hallam is still married to Baldwin that we see him in Havana with Max von Gerlach, promising to spill the beans on the man behind Jay Gatsby. We have to wait another ten years before there is any further news of him. This time the date is 1957 and Hallam is in Palm Springs with former Vaudeville man Joe Frisco and ‘LA Confidential’ columnist, Paul Coates (L.A Mirror). According to the Desert Sun’s Paul Rashall the group had made their way to the Celebrity Lounge of the Rossmore Hotel. [68] An ad in the Desert Sun also suggests that Hallam was acting as agent for a multi-volume collection of academic reference books known as The Great Books of the Western World and the new and ‘startling’ Syntopicon. Billed as a great new concept in self-education, this 54 volume collection was published under the banner of the British-American, Encyclopædia Britannica from its base in Santa Barbara. The man behind the project, Robert Maynard Hutchins, denounced by Hearst newspapers as Communist sympathizer, would later go on to found The Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions. On October 9 1975, some eight years after joining the American Society of Authors, Composers and Publishers, Williams died in New York. He was 68 years old. On October 17 that year, just eight days after his death, the State of New Mexico district Court published their final account and report into the hotly contested estate of Hallam’s aunt, Margaret Turner Williams. Any legitimate claim that Hallam had to be missing millions would now be rendered meaningless. [69]

More Trips to Germany

Max, as it happens, continued his trips to Germany well into the 1930s. On one of those trips he can be seen travelling with wealthy widower Estelle Rolle. On May 7, 1931 the pair set sail on the S.S Hamburg from Hamburg. Details on the ship manifest reveal that Gerlach was then living at the prestigious New York Fraternity Club. His stay there couldn’t have been any more ironic, coinciding as it did with a raid by baton-wielding prohibition agents — the first raid of its kind in a private club. [70] Rolle, meanwhile was residing in St Albans in Queens. [71] Journalist Joe Nocera recently discovered that just twelve months earlier, Gerlach and Rolle had grabbed the headlines when their small auxiliary yacht, the Zara was lost for eight days at sea. The battered schooner was eventually picked-up 45 miles northeast of the Virginia Capes and towed back berth in the Municipal Boat Harbour near Newport, Virginia. The boat had set off from the Marine Basin, New York on November 26 for Miami, intending to stop at Hampton Roads for supplies. It appears that a wild storm had blown in and taken the intrepid pair 500 miles off course. Gerlach, who captained the vessel, told reporters how he had signalled a coast guard vessel, assuring them that they had no liquor on board “but needed plenty of help.” [72]

Although the news report suggests that Max’s yacht, the Zara was owned by Mrs Rolle, the Lloyds Register of American Yachts has no record of a yacht by that name owned by either Rolle or Gerlach. Pat Schaefer, a researcher at Mystic Seaport tells me that there was a sloop Zara in the 1930 Register, designed and built by Herreshoff, but unlike Rolle and Gerlach’s yacht, it was not powered. However, the same Lloyds Register reveals that there was a Max Gerlach listed as the owner of Rambler (formerly, Ramallah) which was an auxiliary sloop, 44’6″ (32′ waterline) x 12’6″, designed by Henry Read and built by Read Brothers of Fall River, Massachusetts in 1896. The owner was logged as Max Gerlach of Bayside, Long Island. It’s former owner was Alex Girtanner, also of Bayside and prominent member of the Bayside Yacht Club. [73] Among Girtanner’s former neighbours on his ‘Old World’ Freeport Bay estate was German aristocrat and flying enthusiast, Baron von Beaulieu-Marconnay of Hildesheim. The Baron’s wife Betsy was Broadway stage star, Marise Naughton. Just several months before the yachting incident, ‘Baron Max von Gerlach of New York’ had been telling reporters about his days as a pioneering aviator at Westfield International Airport. [74] Whether Max was using the story as a means of inveigling his way into yachting and flying circles of von Beaulieu-Marconnay is anyone’s guess.

Mrs Estelle Rolle is an interesting figure in the broader context of Gerlach’s Long Island adventures. In April 1927, Rolle had lost her husband, Edward F. Rolle in a tragic car accident. According to a report in the New York Times, Edward, a chief buyer for the McCrory chain store, was thrown from his car after skidding into a lamppost as he was driving home to Great Neck. It seems he had been playing golf at the nearby Soundview Country Club and was speeding back home to his wife when the accident happened. [75] Just a few years earlier, Edward and his wife had purchased the famous Gracefield Estate, previously owned and built by William Grace, the first Catholic Mayor of New York. Grace was the man who had personally received the Statue of Liberty to New York from Paris in 1885. There was a poetic kind of aptness about it. Not only was it the year of Gerlach’s birth, it was also the year that Scott had originally intended setting the Gatsby novel. Look over a Google map today and you will spot ‘Gatsby’s Pool’ (now closed) where the estate once stood at Gracefield Drive, Kings Point.

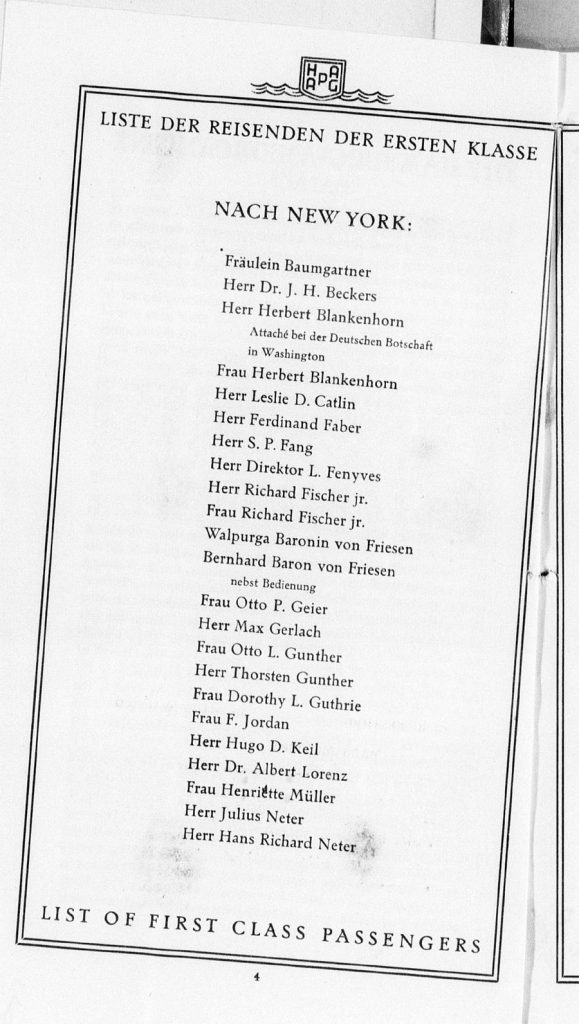

In 1937 there is a record of Herr Max Gerlach travelling first class to Hamburg on the Hansa. Immediately above him on the list is Herbert Blankenhorn. At the time that he made the trip, Blankenhorn was serving as private secretary to German Ambassador, Hans Luther at the German Embassy in Washington. Blankenhorn, who doesn’t appear to have joined the Nazi Party, was later credited as being part of the Nazi-Resistance. The trip was taken as a temporary leave of absence from his role in Washington.

Had it not been for information that has come to light only very recently, it would probably have been fair to regard Gerlach as some tragic, house-bound invalid after blinding himself in his botched suicide bid in Greenwich Village — a sad and aging dreamer scraping a hand-to-mouth existence on the vaguely appetizing scraps of the past. However, Max’s regular first-class flights to Havana and his adventures with Hallam Keep Williams in the spring of 1950 suggest that this was almost certainly not the case. To what extent he was incapacitated is likely to remain unknown, but if there’s one thing we can take away from all this, it is that the 65 year old Gerlach was still pursuing life with a enthusiasm and resilience most folk don’t even possess at twenty.

The Death of Gerlach. The Birth of the Gatsby Legend

Undeterred by Arthur Mizener’s refusal to meet him in person, Max persisted with his letters. In one of the final letters he wrote to Mizener in June 1954 he was assisted by Belle Trenholm, who dutifully related his desperate situation. Although Mizener wouldn’t have known it, Trenholm had her own extraordinary story to tell. Born Belle Grosse in New York to a German father and Bohemian mother, Belle would somehow become entangled in the extra-marital affairs of John William Beauchamp Pinder, a British Canadian mining engineer “with interests in Mexico and Yukon”. Pinder, whose sister was singer and actress Grace Vernon Webber, was reported to have links to President William Howard Taft’s sometime Russian and English ambassador, John Hays Hammond. His brother-in-law was Colonel Horace Webber of the British Army.

In 1909 Pinder, his resume and financial status suitably galvanised by New York’s Yellow Press, had married Broadway chorus girl, Mary Mayo. [76] The following year he had a fling with Trenholm, at that time in the service of Seattle piano teacher and voice coach, Edythe Melville. [77] The affair produced a child — Alwyne Compton Pinder, born 1911. The next six years saw the pair travel around Canada, ostensibly as married couple. For whatever reasons the relationship failed, and in April 1919, Belle married George Macbeth Trenholm, Jr, relocating to California. By 1925 she was back in New York working as an insurance broker. Five years later she returned to Washington State, enrolled at a University and then took up a job as journalist. At some point during the late 1930s, Belle found herself living and working in Japan. Her son Alwyne, a reporter himself, had followed her on the trip and taken up a position at the Japan Chronicle. By 1946 he had found himself working for America’s precursor to the CIA, the Office of Strategic Services, managing a station desk in Shanghai. [78] Chen Tsui-lien, Professor of History at National Taiwan University has recently made the claim that future US diplomat, George H. Kerr, whom Trenholm was corresponding with in Japan in the 1930s, was passing intelligence back to the MID and MIS. Her son Alwnye’s recruitment into the OSS certainly makes this plausible.