As news emerges that actor Ricky Tomlinson and members of the so-called Shrewsbury 24 are to have their 1970s convictions reviewed by the Criminal Cases Review Commission, we look at the role played in that conviction by Woodrow Wyatt’s Red Under the Bed documentary.

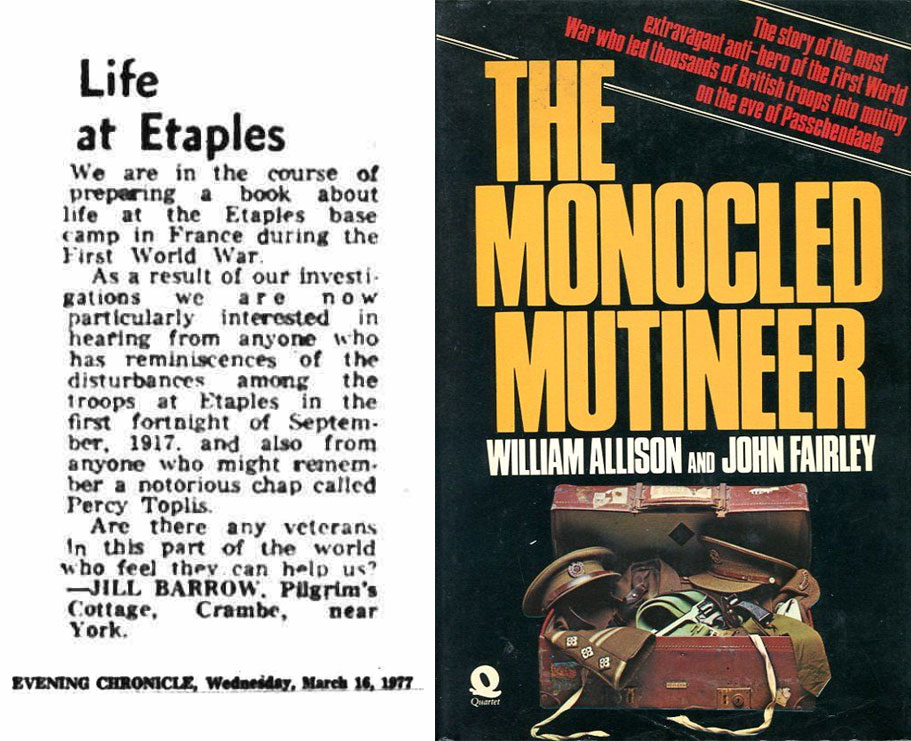

The Monocled Mutineer wasn’t the only occasion that the book’s author John Fairley had found himself at the centre of a ‘Bolshie’ controversy. Just twelve years previously, Fairley, then Head of News and Current Affairs for Yorkshire Television, had produced the studio discussion segment for Woodrow Wyatt’s anti-Trade Union and anti-Communist, The Red Under the Bed documentary. Years later, this same documentary was suspected of playing a supporting role in the conviction of the ‘Shrewsbury Two’ over the part the protesters had played in the 1972 Building Workers Strike. Members of the TGWU and UCATT trade unions had been accused of unlawful assembly and using violent means to intimidate fellow workers. Whilst a total of twenty-four strikers were charged and convicted, media attention had focused on just two: the ‘Shrewsbury Two’ as they became known.

One of the Shrewsbury Two was actor Ricky (Eric) Tomlinson, whose acting talent was discovered in the early 1980s by The Monocled Mutineer’s Alan Bleasdale and Phil Redmond, the creator of Brookside who Fairley had known since his days in Liverpool. Correspondence and papers relating to the Prime Minister’s Office found that Wyatt’s documentary had been commissioned by the Information Research Department. The IRD — whose existence had remained confidential until its closure in the mid-Seventies — had been set-up by the British Foreign Office to provide a ‘counter offensive’ to Soviet ‘Cominform’ propaganda at the outset of the Cold War.

With the support and cooperation of Mi6 and a secret list of approved journalists and politicians, the IRD had set about conducting a series of dirty tricks campaigns conceived to undermine the emerging domestic threat from Communism. And the methods used were as unconventional as they were broad: bankrupting Left-wing groups, burgling Communist Party flats, publishing books — sometimes under highly respectable imprints but more often than not under smaller companies like Ampersand Ltd — and providing subsidies from its £1 million budget to ‘fake news’ specialists within the academic and broadcasting fraternities.

Ensconced in a tall, neat story factory at Riverwalk House in Pimlico, London, the IRD had been shaping public opinion for the best part of 30 years. It was eventually closed on the orders of Anthony Crosland who objected to its links with favoured right-wing journalists who had been dutiful subscribers to its long-range ballistic mailing list whose ‘churnaround’, as far as the department’s targets were concerned, was as devastating as it was quick.

The Guardian’s update on the campaign to clear the names of Warren and Tomlinson on May 26 2020 unveiled newly declassified documents from the Prime Minister’s Office showing how Home Secretary Robert Carr had taken a personal interest in the prosecution of Tomlinson and his men.

At the centre of that personal interest was the Red Under the Bed documentary, written by Woodrow Wyatt, directed by John Phllips and Norman Fenton and commissioned by the IRD on the encouragement of the Conservative government under the leadership of Edward Heath.

One memo from an IRD, dated 21 November 1973, refers to the show’s broadcast on 13 November and reveals how the IRD had a “discreet but considerable hand in this programme”. The Prem 15/2011 file also confirms that the IRD had colluded with the Department of Employment and the Security Service (Mi5) to provide a “large dossier of background material”, including a paper on “Violent Picketing”, to the film’s writer, Woodrow Wyatt.

The programme was, in the words of the IRD a “hard-hitting and effective exposure of Communist and Trotskyist techniques of industrial subversion” — a feather in the cap of the government’s ‘new unit’ and its sister organisation, IRIS. But this had’t stopped them from wanting to go further. Much further.

By Means Foul or Fair

According to the newly declassified files, the documentary was originally intended to conclude with Wyatt’s message that the main aim of Britain’s Communist Party was to take over the Labour Party “by means foul or fair”. To achieve this, Wyatt had carefully stitched together extracts from interviews with leading Communists, Trade Unionists and Industrialists and presented them as evidence to support the IRD’s theory that the Communist Party of Great Britain was infiltrating the Trade Unions using coercive and violent means to create wide-scale civil disruption. There was only one snag. Brian Connell, the former Intelligence man put in charge of the documentary found that Wyatt’s message didn’t comply with the Independent Broadcasting Authority’s standards of objectivity. Wyatt was enraged. The general feeling among executives at the IRD was that the proposed cuts to Wyatt’s commentary had “left the ending of the film rather formless”. To pack the kind of punch that they had in mind, TV audiences would need to come away from the show utterly convinced that the ‘violent acts of picketing’ organised by Warren and Tomlinson were Communist acts of industrial subversion and that its bid to seize control of the Labour Party and British pits was urgent and real.

The documentary’s ‘principal witness’ was News of the World journalist, Simon Regan, a sleazy tabloid hack specializing in ‘rumour, gossip and nudge-and-wink innuendo’ whose series of reports on violent picketing in November 1972 had been completed under the direction of the IRIS in the first place. The picture that Regan painted for the viewers was a cruel and disturbing one: “I was witness to people being shaken from the scaffolding … I was witness to men being punched and kicked.” Regan went on to describe how the Communist Party ‘Action Committee’ would bus-load pickets into towns and hunt men down. According to the 30-year old journalist, they even went to his pub and threatened to shoot him through both legs.

As a result of the IBA’s misgivings, broadcast was shelved for some six months before Connell had a brainwave. Wyatt and the IRD found that they were able to get around the cuts enforced by the IBA by tagging on a special discussion programme that would immediately follow the main film. The studio discussion segment would be chaired by Richard Whiteley with a panel that would include Barbara Castle MP, Geoffrey Stewart-Smith MP and Alan Fisher. And it was this discussion segment — with John Fairley drafted in as Executive Producer — that allowed Woodrow Wyatt to make many of the points that had been “excised” from the film by the IBA’s standards committee (Prem 15/2011, p.18, Letter from Thomas Christopher Barker to Mr Norman Reddaway).

The finished programme was broadcast on November 13 1973 just as the prosecution was closing its case against Tomlinson and Warren at Shrewsbury Crown Court. And whilst there’s no evidence to suggest that Wyatt, Fairley or other members of the production crew knew the extent to which they were being manipulated, the impact of the film was brutal: the jury who convened in the weeks following the programme’s broadcast found both men guilty of unlawful assembly, causing an affray and conspiracy to intimidate. On December 19 1973, Justice Hugh Mais handed Warren a three year prison sentence and Tomlinson was awarded two years. Four other men in the so-called ‘terror squad’ received lesser sentences.

It should come as no surprise to learn that Justice Hugh Mais’ cousin was author, broadcaster and former journalist, S.P.B. Mais whose publisher, Johnson Publications and its assistant editor, Geoffrey Baber, were deeply enmeshed in the shamelessly right-wing Monday Club, alongside former Mi6 deputy director, George Kennedy Young. Young was subsequently accused by Labour MP John Mann of having played a backstage role in the whole shameful Shrewsbury drama.

In 1917 the ruckus at Etaples had erupted over conditions in the army camps. Some 50 years later it was over conditions on building sites.

Tomlinson left prison in 1975, backed for early release by the Secretary of the TUC. Just as convicted mutineer James Cullen had pointed the finger at Soviet-funded agitators within the British Army for the ‘disturbances’ at Etaples Base Camp in 1917, it was the belief of senior Conservatives that the strike action devised by Tomlinson and his friend, the militant Des Warren, had the full backing of the Communist Party of Great Britain and Soviet Russia — whose adored leader, Vladimir Lenin, Cullen would eventually serve as a founding member of the CPGB.

In the mayhem of the moment, were parallels being drawn among patriarchs at the IRD between the disturbances at home and some dimly remembered riot at a military base camp in France?

Within months of Tomlinson’s release, a little known paper by two former Oxford academics had been published in Past & Present, a Marxist leaning quarterly published by Oxford University Press, founded by editor — and Balliol Communist — Christopher Hill. The title of the paper was Mutiny at Etaples Base in 1917 (Past & Present, Nov 1975, No. 69). It would prove to be a pivotal moment in the journey of Bleasdale’s drama from fractious war-time disturbance to Tory-seeking projectile, and came just ten weeks after Ricky Tomlinson’s storming of the gallery at the TUC conference in Blackpool. The paper’s authors, Gloden Dallas and Douglas Gill were scholarly roughnecks with a long enduring passion for Revolutionary Socialism. Dallas was an uncompromising and meticulous Socialist-Feminist historian whilst Gill’s status and reputation had been blisteringly assured by his proximity to the punkish pan-anarchist newspaper, Black Dwarf in the 1960s. The rag’s doubly heavy sans serif typeface couldn’t have made its agenda any clearer: Agitate, Educate, Organize. It was a far cry from the more procedural and stuffy efforts Gill had produced for the New Left Review — ‘Cold War Origins’ in 1966, and ‘Common Men in Vietnam’ in 1968, a slightly awkward conflation of smug morality and greenhorn foreign affairs.

After the temporary departure of Tariq Ali in 1969, Gill had found himself directing the newspaper’s editorial and production policies. A headline-grabbing raid by Scotland Yard on its Carlisle Street offices the previous year had endowed it with a gravitas and influence traditionally beyond the reach of fringe student rags in Britain. Among its founding members were Hackney activist, Roger Tyrrell, Socialist Feminist Shelia Rowbotham — a Leeds-born pal of Gloden Dallas — and Clive Goodwin who would eventually become literary agent for Bill Brand writer, Trevor Griffiths, Dennis Potter and Jim Allen. It was a profoundly talented, hugely combustible mix, creating a stormy, litigious vacuum that would over its four-year history suck in contributions from era-defining icons John Lennon and David Hockney, as well as political and cultural game changers like Fidel Castro and Bertrand Russell. Gill would eventually leave the paper with a windfall donation from a South American millionairess and embark on a less successful venture with Labour activist and Indian investor, Vidya Sagar Anand with the encouragement and support of the Castro-backing editor of the International Idiot, Jean-Edern Hallier.

Black Dwarf co-founder Clive Goodwin would die in Los Angeles, in the company of his client, Trevor Griffiths. The pair had been discussing the script for Reds (1978) with Warren Beatty at a hotel in Beverly Hills when Goodwin was suddenly taken ill. Thinking that Clive was drunk, the hotel called the LAPD and Goodwin died in Police custody on November 15th 1977. An autopsy would later reveal that the ‘drunkenness’ he’d been experiencing had been the onset of a cerebral haemorrhage.

Des Warren who had been imprisoned like Tomlinson for ‘conspiracy to intimidate’ never recovered from his spell in prison and died after a long battle with Parkinson’s Disease in 2004. Tomlinson was a little more fortunate. French-Latvian director Roland Joffé, an associate of Alan Bleasdale from his days on Play for Today, handed Tomlinson a lifeline with a role in ‘United Kingdom’, a typically Left-Wing take on modern Britain written by Joffé’s friend, the Socialist playwright, Jim Allen. Attendance at a series of Worker’s Revolutionary Party meetings in the 1970s had seen Joffé and Allen both blacklisted at the BBC as possible security risks. Joffé’s response had been to direct the hard-hitting political drama, Bill Brand with Clive Goodwin’s Reds writer, Trevor Griffiths, the former editor of Labour’s Northern Voice who gave Revolutionary Marxism such an emotional human depth with films like Rank and File and Land and Freedom.

In his 2002 autobiography Tomlinson makes little secret of the fact that his success was down to Joffé, even going to so far as to name his beloved bull mastiff dog after him. In 1988, The Monocled Mutineer’s Alan Bleasdale would make an abortive six-week trip to the Soviet Union to research a film idea for Joffé and a film company in Hollywood. Joffé had heard rumours of an obscure Russian enclave in Moscow that had never been touched by Communism, but which was now facing the inevitable economic and cultural reforms that would arrive with Glasnost. Bleasdale came back empty-handed, having found nothing to substantiate the idea. He claims never to have heard back from Joffé (The Manacled Mutineer, The Guardian, May 30 1991, p.22).

Roffé would embark on a long term relationship with Monocled Mutineer star, Cherie Lunghi who had collaborated with both Joffé, Allen and the drama’s producer Richard Broke on other projects over the years. Their daughter Nathalie was born just days before the first episode of the series aired at the end of August 1986.

More Cold War Games

John Fairley’s own experience in Soviet-themed productions was extended by the very well received, Cold War Games with Jonathan Dimbleby (1982) and Red Empire, a seven part mini-series produced by Yorkshire Television. The programme was presented by Robert Conquest, an indomitable former staffer of the secretive IRD who had commissioned ‘Red Under the Bed’ 1. Conquest had at one time been contracted to the department’s Ampersand Ltd and Bodley Head, the Mi6-supported publishing fronts that churned out hundreds of IRD-subsidised books over a prodigious twenty year period.

By this time the IRD had been disbanded and Conquest was continuing his activities as a visiting scholar and research associate at Harvard University’s Ukrainian Research Institute — the centre of anti-Communist research in America.

Fairley’s creative encounters with crisis and insurrection went back further still. In 1976 Fairley had found himself roped in as Executive Producer on General Strike Report: May 1926 with Robert Kee — a close friend of IRD adviser George Orwell and a partner of Russian spy, James MacGibbon. The ambitious 15-minute show was a day-by-day, blow-by-blow account of the 1926 General Strike called by the TUC that culminated on May 12, 1976, the 50th Anniversary of the strikers’ defeat. The “beautifully simple idea” telescoping the then and now, covered the events of the strikes in 15-minute news bulletins each night after News At Ten. Fairley’s format, mashing the vintage film clips with the usual roll-call of talking heads and news presenters, achieved a thrilling simultaneity with the past. Its effect, deliberate or not, was to pump considerably more urgency into the prospect of industrial collapse and the tumultuous emergence of race riots in 1970s Britain.

The show’s uniquely postmodern, self-referential ‘real time’ approach with Kee impeccably cast as his own First Report persona, was something of a first in British Television. The series didn’t just represent a new way of engaging with the past, it offered an invaluable insight into how information could be manipulated and how reporting had evolved. As Peter Lennon wrote in The Sunday Times, “the people of 1926 were never informed like this.”

Like much of the industrial action backed by the TUC in the early 1970s, the Tories had convinced themselves that the nine day general strike in 1926 had been provided with financial aid from the Soviet Republic. And with the sudden resignation of Harold Wilson taking place just weeks before the series was aired, Britain seemed to be heading towards certain decline. A rumoured coup d’etat by retired military top brass only added to the paranoia.

Fairley and Kee next collaborated on Faces of Communism, broadcast shortly after the publication of The Monocled Mutineer in 1978, when Fairley served as Yorkshire TV’s Head of News and Documentaries.

In 1982, Fairley and Kee were reunited again when they worked together on the launch of pioneer breakfast show, TV-AM with Kee drafted in as journalist presenter and Fairley as Managing Editor. One of the guests who appeared on the day of the launch was Jennie Erdal, who talked to TV AM shareholder and presenter David Frost about Red Square, a must-read Russian spy thriller published just that week by Fairley and Allison’s publisher (and Frost’s business partner), Naib Attallah. Some 14 years earlier Frost had interviewed Douglas Gill’s Black Dwarf colleague, Tariq Ali on Frost On Friday. Sitting alongside 77 year-old Suffragette Lilian Lenton and black rights comedian Dick Gregory on the evening of Friday 6 September 1968, Ali discussed the role that he and the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign were playing in encouraging young American conscripts to mutiny. 48 hours later on Frost on Sunday, The Beatles would debut their new double A-side single, Hey Jude and Revolution, the latter inevitably leading to a shirty correspondence face-off between John Lennon of The Beatles and Ali’s co-editor John Hoyland.

Just four days after the launch of the first full edition of Black Dwarf on June 1st 1968, Robert Kennedy was shot dead in the ballroom of The Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. His assassin was 24-year old Palestinian, Sirhan Sirhan, furious at the support that America and the President had shown for Israel during the previous year’s Six-Day War. Shortly before the first anniversary of Black Dwarf’s launch its editors Tariq Ali and Fred Halliday officiated at the very first meeting of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign in London. The marchers assembled at Hyde Park before marching down to Trafalgar Square for a mass meeting. Ali was one of over 2,000 demonstrators shouting “Down with Zionism”. Twenty year later Ali’s talk show mentor, David Frost scored an exclusive interview with Kennedy’s assassin in Soledad Prison in California. The interview was broadcast on February 20 1989 by America’s Inside Edition, launched just three weeks previously with Frost as anchorman. In his first ever public interview Sirhan explained his motives for killing Kennedy. Within days of the broadcast, Frost had been dismissed by the show’s producers and the State of California had banned all further TV interviews with inmates at all state prisons. What prompted either of these decisions isn’t clear but there may be a clue in how the interview was obtained.

At the time of the assassination the LA Times ran a story of how four Palestinian lawyers were on their way to America to represent the assassin in court. The team had been organised by Henry Cattan, a well known Beirut attorney and consultant to American firms. Among the four men were Ahmad el Khalil, Mohamed Barad’h, Hussan Hawwa and Fouad Attallah. The last man, Fouad Attallah, born in Nazareth in 1904, had been educated at the American University of Beirut before taking his place at the Palestinian Law Institute in Jerusalem. Among the many illustrious names in his family was Naim Attallah, owner of Quartet Books and business partner of David Frost.

Frost’s position in the anti-war movement and his assiduous, light-bearing role in Sixties counter-culture in general, should never really have been in any doubt. His Methodist father, the Reverend W.J Paradine Frost had been a loyal and respected member of Fenner Brockway’s ‘No More War Movement’, the Revolutionary Socialist successor to the no-less radical No-Conscription Fellowship of the Great War (Sussex County Times, 15 November 1930). And in case you didn’t know already — Frost had also trained as a preacher.

To add to the list of coincidences and curiosities, it transpires that Tony Essex — Fairley’s mentor at Yorkshire Television — even had the distinction of serving Monocled Mutineer fall guy, Alasdair Milne on The Great War series first broadcast in 1964.

Middle East Quartet

One could go cross-eyed looking at the various links between Independent Television and the Security Services were it not for the sharp, clear focus that the book’s publishers Quartet and its proprietor, Naim Attallah bring to the whole affair. By the time that The Monocled Mutineer was published in January 1978 the Palestinian-born entrepreneur had already enjoyed considerable contact with past and present members of Secret Intelligence Services and their friends. Among those sharing their innermost thoughts and secrets with Attallah and Quartet were Brian Sewell (a close friend of Soviet Double Agent, Anthony Blunt), Nazi sympathizers Leni Riefenstahl and Diana Mosely, former Soviet prosecutor, Fridrikh Neznansky and Russian dissident Edward Topol. The latter’s novel about a Kremlin coup was translated by Attallah’s ‘Russian List’ specialist and ghostwriter, Jennie Erdal — wife of former Communist organiser, trade union shop steward and now author, David Erdal 2. It was a curious move in the circumstances, as Quartet’s founders had been four former executives of Granada Television, the regional North West TV station that Mi5 continued to investigate as a possible Communist front well into the 1970s (see: KV 2/3222, National Archives) 3. There was nothing like courting trouble.

Under the direction of Attallah, Quartet would embark on a publishing campaign not unlike that of the Ampersand Ltd — the London-based front company set up by former Daily Mirror journalist, Leslie Sheridan of the IRD in the 1950s. After recruiting translator Jennie Erdal in 1980, Quartet would publish a steady stream of titles written by Soviet Exiles and anti-Communist intellectuals and wrestled into English by its indefatigable resident linguist over a prolific ten-year period, starting with the Memoirs of Leonid Pasternak and the aforementioned spy novel, Red Square. But if there was any evidence of a creeping right-wing bias into Granada’s flagship publishing arm, it was not to be found so much in Quartet’s output as in its contacts.

Among Attallah’s most beguiling and unconventional associates, was the notorious Conservative Jonathan Aitken, the man who had joined Toplis tracker John Fairley for the launch of Yorkshire’s flagship evening news programme Calendar at the end of July, 1968. Aitken, who served 18 months in Pentonville prison for lying to Police during the course of a Saudi Arms investigation, had known Attallah since their time together at investment consultants to the Middle East, Slater Walker. The pair went on to collaborate on several ambitious ventures, even reuniting with John Fairley for Yorkshire Television’s three-part mini series, The Arab Experience in 1976. The series was based on the book by ‘Crazy Bear’ Antony Thomas, Michael Deakin (another Aitken regular who had co-produced General Strike and Johnny Come Home with Fairley) and Robin Constable.

Scots on the Rocks

The Aitken name cropped up again when Jonathan’s sister Maria Aitken starred in the explosive revolutionary drama, Scotch on the Rocks (1973). Her co-star in the series was actor and writer Leslie Glazer, the man whose original 1974 play about the Etaples Mutiny was rejected by the BBC’s Head of Scripts, Peter Kosminsky.

As it turned out, Kosminsky, who was poached from the BBC by John Fairley and Yorkshire Television in 1985, was unhappy about the Glazer’s uneasy mix of fact and fiction, and faced with a much depleted budget was unable to accept it. In an interview with the Daily Mail in September 1986, Glazer said he had felt shattered when he had watched the first episode of Bleasdale’s drama, containing as it did, all the scenes to which the BBC had objected to in his version.

The similarities between The Monocled Mutineer and Scotch on the Rocks were extraordinary. Based on a novel by Conservative MP Douglas Hurd (Private Secretary to Edward Heath at this time and father of Tom Hurd, the once touted Chief of Mi6) and Andrew Osmond, the drama tells the story of Mi5 and Special Branch officers infiltrating the Scottish Nationalist paramilitary organisation, the SLA in an effort to thwart a separatist military coup. Jonathan’s sister Maria Aitken played Sukey Dunmayne, “an aristocratic bird” who had found her way into a Glasgow radicals bed, played by Scottish actor, John Cairney (Daily Mirror, 12 May 1973, p.12). In a twist that would no doubt have pleased the Information Research Department, it turns out that Cairney’s Scottish paramilitary organisation has links to French Communist Party leader Serge Bucholz, played by Leslie Glazer. In one of the final scenes Aitken and Glazer’s characters abscond to Moscow to evade arrest. Maria would eventually resurface as a ‘talking head’ in Women, a book published by Jonathan’s business partner — and Monocled Mutineer publisher — Naim Attallah in 1987.

The drama’s author, Douglas Hurd had conceived it during his time as Foreign Affairs officer with the Conservative Research Department — a top drawer ‘special ops’ unit, not unlike the IRD, that had been turning out Tory agitprop ever since the appointment of notorious Mi5 officer, Joseph Ball as its Director in 1930. Ball, believed by many to have played a central role in the Zinoviev Letter scandal that brought down Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour Government, had perfected the CRD’s dirty tricks campaigns over a golden 10 year period. It was Ball’s Lonrho associate, Edward Du Cann who brought in Hurd from the Foreign Office where he served as First Secretary for Political Affairs in Rome. He was actually in Rome at the time of the famous ‘Spy in a Trunk’ scandal (Daily Mirror 19 November 1964, p.1). Just four years previously Hurd’s predecessor in Rome, Harold Charles Lehr Gibson was found shot in his Rome apartment. Formerly with the British Legation in Riga, and serving as Head of Station for Mi6 whilst in Rome, Gibson’s name was among several Western Diplomats accused of treason by Czechoslovakian Communists (Ex-Diplomat Found Shot in Rome Flat, Evening Telegraph 25 August 1960, p.29). His death came less than a month after a TNT bomb on a time fuse was left in the forecourt of the Soviet Embassy in Rome. Gibson’s wife, the White Russian dancer, Ekaterina Alfimova Leschenko ran a ballet school in the capital.

As Hurd was Private Secretary to Prime Minister Edward Heath at the time that the Red Under the Bed documentary was aired, it’s almost certain that he and his immediate superior, Robert Armstrong — who had personally requested the transcripts of Wyatt’s show back in January 1974 — were keenly aware of the programme’s intent and its proximity to the Security Services. Hurd’s colleague Armstrong can be seen to write on a memo addressed to Cabinet Secretary, Sir John Hunt, “the Prime Minister (Heath) has seen the transcript of Woodrow Wyatt’s television programme ‘Red Under the Bed’. He has commented that he wants as much as possible of this sort of thing. He hopes that the new Unit is now in being and actively producing” (PREM 15/2011, National Archives).

Scotch on the Rocks was an audacious, provocative broadcast from start to finish and immaculately timed to coincide with the end of the Scottish Conservative Party Conference, during which some of the party’s savvier members sent out a clear message: if the government didn’t devolve certain powers and a bigger share of the North Sea Oil profits to Scotland, the Left-Wing militants and extremists would seize control of its ‘devolution’ movement. And just to emphasize that threat, the 80-year old founder of the National Party of Scotland, Wendy Wood was quietly removed from the hall at the Conference just one day before Scotch on the Rocks was broadcast.

The series sent shockwaves throughout Scotland. The BBC Programme Complaints Commission upheld criticism by the Scottish National Party that its five-part thriller had seriously impugned the party by suggesting it was involved in using violence for political ends.

We consider that the first episode of the series would leave the viewer with the impression of the SNP being involved in violence. We are confirmed in this belief by some of the reactions of members of the public, as revealed by the record of viewers’ telephone calls kept by the BBC and the press after the first episode was broadcast.”

Ombudsman, Sir Edmond Compton’s report on the offence caused to the SNP by Scotch on the Rocks

As with Bleasdale’s Mutineer and Fairley and Kosminsky’s Shoot To Kill, the BBC responded to these criticisms by promising never to show the series again. Not that the hue and cry surrounding its broadcast had any detrimental impact on the Scottish National Party. Quite the opposite, in fact. The energy the drama had pumped into the mythical ‘home rule’ movement resulted in Harry Selby losing one of Scotland’s safest Labour seats — Glasgow Govan — to the SNP’s Margo MacDonalds. With a re-engerized It’s Scotland’s Oil campaign the party won a further six seats in the General Election that followed. By the time of the 1974 October re-run the SNP were taking a third of the Scottish vote. Its success was only to be repeated by Nicola Sturgeon.

Whether Aitken and his Middle Eastern partners had their eye on Scottish Oil or whether there was a sincere attempt to highlight the potential dangers of Scottish separatism, it seems uncanny that programmes like Red Under the Bed, Scotch on the Rocks, The Monocled Mutineer and Shoot to Kill should each have such devastating payloads, and such a recurring cast of characters taking up roles behind the scenes. One thing is certain, by the time of the February 1974 election, Aitken was putting the issue of North Sea Oil at the centre of his election hopes in Thanet East. Speaking at a meeting in Ramsgate, Aitken told his constituents that Ramsgate Harbour could well develop several thriving services “connected directly or indirectly with the oil industry and its many spin-offs ” (Cash in On North Sea Oil Boom, Thanet Times 26 February 1974, p.5)

Strangely, a look at Jonathan Aitken leads us back to an event in the lives of Gloden Dallas and Douglas Gill, authors of the first historical account of the Etaples Mutiny published by Past & Present in 1975 — just two years after Scotch on the Rocks. The episode in question dates back to the early 1960s when Aitken was a second year law student at Oxford University. According to Shelia Rowbotham’s autobiography, Promise of a Dream (2000), a minor civil liberties case had flared up in Oxford. Richard Wallis, an anarchist student who was sharing a house with Douglas Gill and Sheila’s then boyfriend Robert Rowthorn, had been prevented from selling copies of the anti-war newspaper, Peace News on Oxford High Street. Wallis’s arrest by Police came as no big surprise. The students had been under surveillance for months, all four being active in the non-violent direction group, Committee of 100 and various CND focus groups. The 20 year-old Jonathan Aitken was recruited by Gill and Rowthorn to defend Wallis in court. Gill’s friend and co-editor at Black Dwarf, Tariq Ali would later describe Aitken as a ‘thick rich kid’, but any animosity between Ali and Aitken during their time at Oxford together is likely to have been confined to the usual harmless battle raps going on at the campus extremes. In fact, the pair were regular rivals for the Presidency of the Oxford Union.

In 1967, the hatchet must have buried temporarily at least, as their names were printed together at the top of a list of 64 prominent members of London society calling for the decriminalization of cannabis. A full page advertisement had been taken out in The Times and paid for by The Beatles. At the very top of the signatories — even above Paul McCartney and John Lennon— were Revolutionary Socialist, Tariq Ali and future Defence Secretary, Jonathan Aitken (The Law Against Marijuana is Immoral, The Times July 24 1967) .

The man most likely to have brought Aitken and Gill together was fellow student Nicholas Zvegintzov, the editor of Oxford Circus, a riotous student rag trading in irreverent political satire. Aitken served as its Union correspondent and had contributed several pieces. His proximity to the rag earned him a lofty rebuke from his Uncle Max, Lord Beaverbrook, who was reacting to a ‘blasphemy scandal’ which had featured in a report in The Times. It appears that complaints had been made about one of its covers which showed a picture of the Madonna and Child with the Madonna saying: “I haven‘t told his father yet” (The Times, Nov 1962). Lord Beaverbrook’s response was to ask his wayward nephew if he believed in God, and having been told yes, conceded that the incident had been “ in bad judgement rather than blasphemy” (Heroes and Contemporaries, Jonathan Aitken).

In the mid 1960s, Aitken’s editor at Oxford Circus, Nicholas Zvegintzov would win a scholarship to study business administration at Berkeley in California. There ahead of him, and playing virulent roles on its lecture circuit, was Gill’s housemate Robert Rowthorn and radical Indian economist, Ajit Singh. Within years of arriving Zvegintzov had been suspended, this time over an “obscenity incident” in the campus magazine, Spider. The hearings that followed were the first real test of the resolutions made on Free Speech on December 8th the previous year by the Academic Senate. His Berkeley associate, Mario Savio, leader of the militant Free Speech Movement would subsequently enrol at Oxford and become a leading exponent of the emerging New Left.

For the Zvegintzov family, the chronic turbulence of radical politics was not entirely unfamiliar. Nicholas’s grandfather was the Russian Octobrist and Zemstvo leader Colonel Alexander Ivanovich Zvegintzov, a formidable member of the Progressive Bloc who had been elected to the Second, Third and Fourth State Dumas in Russia between the years 1907 to 1917. Seeking sanctuary as a political refugee in England in the immediate aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution, the family were the subject of an Mi5 watchlist, some members of the Services being more than a little cautious over the business and family connections between Nicholas’s uncle Dmitri Zvegintzovs and Count Alexis Ignatieff in Paris. Reports had been emerging that the Count was showing support for Stalin’s Soviet, and worse still, assisting the Germans. In a letter to Mi5 dated February 20 1922, the Russian Consul-General Ernest Gambs Russia’s Military Agent in France had presented a memorandum to Prime Minister Aristide Briand urging him to recognise the Soviet. According to the message he was now working as a Soviet agent “with instructions to persuade loyal Russians abroad to enlist in the Red Army. According to the same file, his brother and business partner, Nicholas Ivanovitch Zvegintzov was believed to have stayed in the Soviet Union having already enlisted with Lenin’s army (TNA, KV-2-1909).

One of the referees supporting the family’s request for naturalization was Sir Bernard Pares, the historian and British diplomat who had served with the Foreign Ministry in St Petersburg during the war. In a letter dated May 30 1938, Inspector Hay of Special Branch states that Pares declared them worthy of naturalisation on the grounds that Dmitri Zvegintzov had been “a courageous officer in the Great War and also against the Bolsheviks”. Hays would never have been able to predict that Pares would spend the last years of his career speaking favourably of Stalin’s Soviet. Another name mentioned in the family’s file is 21 year-old Alexis Archangelsky, whose father would work with radical Soviet director, Sergei Eisenstein on scores for his films. A Special Branch report dated 1933 had Alexis staying as a paying guest at Dmitiri’s home in West Kensington.

Despite a comment in the family’s KV2 Security records to the “untimely destruction” of his own file, Nicholas’s father Michael Zvegintzov was given clearance to serve in the Political Intelligence Department of the British Foreign Office, before his transfer to the Political Warfare Department of the Supreme Headquarters during the war.

Further Acts of Rebellion

As far as The Monocled Mutineer was concerned, had John Fairley’s experiences during any of these documentaries, and his close encounters with past and present staffers of the IRD or even his contact with Jonathan Aitken — wittingly or unwittingly — stoked his interest in the Toplis story? Had rumours been circulating for years that Toplis had been sought — if not mistakenly, then optimistically — as a Bolshevik agitator by the hysterical Tory elites in the aftermath of the Etaples riots? Were there secrets still to unlock after all these years?

Inevitably, John’s role at Yorkshire Television would have seen him roped-into all manner of productions, whether it was league table pub games with cricketing legend Fred Truman or the wackier ‘Mysterious World’. But it was those with a hard-hitting, political edge — like those with his longtime collaborators Simon Welfare, Michael Deakin, John Willis and Robert Kee — that seemed to capture his imagination 4. Could the same be true of Fairley’s co-author William Allison?

One clue might be found in the address that Allison was using in newspaper appeals in August 1978, shortly after the first imprint of the book was published by Quartet. Allison said he was working on a follow-up to The Monocled Mutineer. The ad told readers that Allison was now engaged in the compilation of a more ‘comprehensive account’ of acts of rebellion within the armed services during the period 1917 to 1920, and that he would be grateful for further ‘first hand accounts and recollections’. The address he used to make this request was 7 Makepeace Avenue in Highgate’s Holly Lodge — just 300 yards from the Tomb of Marx in Highgate Cemetery and some 200 yards from the Trade Delegation of the Russian Federation on Highgate Hill. Highgate was and remains the capital of Marxist Communism in the UK, if not Europe; something of a lighthouse for anxious Left-wing souls with the cash and determination to steer clear of convention.

If Communist agitators had been active during any of the riots, as proposed by mutineer James Cullen, later of the Communist Party of Great Britain, then Allison’s highly visible, and very symbolically-charged address would almost certainly have attracted the attention of veteran British Marxists. To the average militant ‘Leftie’, it would have seemed like the heavenly wail of a mermaid, luring the cheerfully distracted sailor to the thrashing rocks of his lighthouse.

A few years prior to Allison’s appeal, Makepeace Avenue had featured in a headline grabbing spy caper. In September 1971, Soviet defector, Oleg Lyalin, serving as a representative at the nearby Russian Trade Delegation contacted Allison’s Daily Express offices wishing to disclose information about K.G.B. activities in exchange for a new life with his Russian secretary. Beaverbrook’s Express office contacted M.I.5, and as a result of his disclosures, 105 Soviet officials, many of them housed in the Holly Lodge Estate of Highgate, were served expulsion orders. One of those under scrutiny was the Chairman of the Moscow Narodny Bank, Nicholai V. Nikitkin, whose house was on Makepeace Avenue. Within days, Highgate’s Holly Lodge Estate was being dubbed the ‘Village of Spies’. Curiously, one of its most high profile residents was Denis Healey, the MP for Leeds East, who only the previous year had been serving as Secretary of Defence in Harold Wilson’s government. Within weeks of the ‘Village of Spies’ caper hitting the headlines, Healey was involved a car accident in London’s West End. The MP, now serving as Shadow Defence Secretary, was duly breathalysed by Police who made a deliberate point of leaking the negative results of a blood-alcohol test — and details of Healey’s Holly Lodge home — to the press. As a former member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, the potential fallout was considerable.

For more details regarding the Lyalin case, see: Information Research Department: defectors; Oleg Lyalin, FCO 168/4589, National Archives.

Mi5 would later call the Holly Lodge episode a major turning point in Cold War counter-espionage operations in Britain.

At the time that his Highgate ‘mutinies’ appeal was published, Allison was CEO at Syndicated Features Ltd — an international newspaper and magazine agency peddling syndicated content across a broad range of magazines and red top newspapers from the Holborn district of London. The company’s directors at this time, were John Radgwick and Frank Durham 5. In the late-1950s Durham had joined RAF Intelligence. Here he trained as a Russian linguist at its Joint Services School at Crail in Fife, one of Britain’s first ‘post-Bletchley’ gambits in its emerging Cold War efforts. Staffed by a bizarre assortment of acrimonious White Russian exiles and defectors, the school would inevitably turn out successful Special SIGINT agents like journalist and producer, Leslie Woodhead. And perhaps just as inevitably, it would attract attempts at penetration by the KGB.

As Associate News and Features Editor of the Daily Express at the time of the Highgate spy-ring sensation it seems unlikely that the significance of his Highgate address could have been lost on Allison — especially as he and Fairley’s book had just sent a fresh wave of insurrection rippling through the long dead Etaples affair. Had Allison, like his co-author, encountered whispers about Toplis previously? During his time with Daily Express, perhaps? It’s an intriguing possibility, certainly.

In a file dated March 1966, just as crippling national strike action loomed, the Information Research Department had told the Cabinet Office that it had received suitable material by Mi6 to place in British daily newspapers. Allison’s Daily Express was among them.

Back to the Information Research Department

Sandy Trotter, the man who had brought Allison across from the Scottish Daily Mail to the Scottish Daily Express on the strength of his reporting on the Stone of Destiny heist in 1951, had also been responsible for hiring journalist Hector McNeill. McNeill, the industrious yet foolhardy deputy at the Foreign Office under Clement Atlee, would subsequently play a very active role in the founding of the IRD, even going so far as to recommend his own personal assistant Guy Burgess to Christopher Mayhew, as someone who was “uniquely qualified for IRD work”. Burgess would later earn no small amount of notoriety for his alleged role in the Cambridge Spy Ring (A War of Words: A Cold War Witness, Christopher Mayhew, I.B. Tauris, 1998).

The man who owned the Daily Express at this time was Sir Max Aitken, a close friend of Sandy Trotter and the uncle of Jonathan Aitken who had been recruited alongside Trotter’s daughter Pat Sandys and John Fairley at the launch of Yorkshire Television in 1968. For three years in the nineties Jonathan also served as headline-prone chairman of the unashamedly hush-hush Intelligence forum, Le Cercle and was long rumoured to have been working with Mi6 and the CIA. But as it turns out, ‘backstage politics’ was in the blood.

At the time of the Etaples Mutiny, Jonathan’s Uncle Max had headed-up the Ministry of Information, the immediate precursor to the IRD. If anyone would know the truth behind the Etaples Mutiny, it was the former ‘Minister of Propaganda’ Max Beaverbrook. The recruitment of Uncle Max to the post in February 1918 had arisen from growing war-weariness among the troops. Appointing two self-made Press Lords into the government’s leading propaganda departments were just two of the steps taken by Lloyd George to improve the morale of soldiers and public alike.

Just two years after the IRD had taken up positions at the Daily Express, Aitken would join John Fairley and Richard Whiteley for the launch of Calendar at Yorkshire Television. Some 14 years later Aitken would reunite with Fairley and Robert Kee for the launch of TV-AM. It was a reunion that would end in disaster when it was found that the station was controlled illegally by Saudi stakeholders. An investigation by the Observer found that the Saudi Royal family had been routeing cash through an Aitken front company in an effort to promote an Arab bias.

The Daily Express’ chief contact with Mi6 was Allison’s tireless political reporter, Chapman Pincher who had made his life’s mission to track down and expose Cold War spies operating in 60s and 70s Britain. Pincher would later hook up with Aitken in the no less controversial Roger Hollis and Spycatcher affair (1980-87). Pincher’s work at the Daily Express had also seen him cover the Profumo Scandal at a time when John Profumo (and Christine Keeler, one might assume) was his friend.

Did the closure of the IRD during The Monocled Mutineer’s conception in 1977 signal the end of this ‘secret’ department or did it simply mark a change in its tactics which had grown grossly out of touch with the times?

Whatever the truth of the tale, there is some consolation in knowing that the UK has and continues to produce challenging dramatic narratives to ongoing threats to freedom; whatever their fidelity to historical accuracy and whoever they deceive and hurt in the short term.

And that just has to be a good thing. Right?

Notes

1 Several months prior to The Monocled Mutineer being published, the Information Research Department was wound-down and closed. Ironically both Ricky Tomlinson (the man convicted as a result of the Red Under the Documentary) and Richard Whiteley (the show’s presenter) ended-up fronting Channel 4’s flagship programmes Brookside and Countdown on the day of the channel’s launch on Nov 2 1982. Despite several appearances on Whiteley’s Countdown show, Tomlinson would subsequently accuse Whiteley of working for Mi5 (a misrepresentation of the facts, if ever there was one). The Red Under the Bed documentary is back in the news as the Court of Appeal announces that it is due to review Tomlinson and the Warren’s convictions. See Ricky Tomlinson’s criminal convictions to be re-examined. The IRD & IRIS had worked with Simon Regan of the News of the World to produce the dossier on ‘violent picketing’ used to support the documentary. Regan, who went on to found the Scallywag journal, would also appear in the film.

2 see: Asking Questions: An Anthology of Encounters with Naim Attallah, Quartet Books, 1996, In Conversation with Naim Quartet Books, 1998 and Of a Certain Age, Naim Attallah, Quartet Books, 1992). Their sister company, Namara Films Ltd (with David Frost as co-director) produced 1982’s Brimstone and Treacle, directed by Richard Loncraine and written by Dennis Potter.

3 Quartet’s early list of bestsellers included The Joy of Sex and The Socialist Challenge, the latter written by Harold Wilson’s political adviser Stuart Holland. The 1976 deal meant Attalah and his Namara Group acquired an 87% control of Quartet. Namara Directors included David Frost, jeweller John Asprey and Sheikh Najib Alamuddin whose Great Niece Amal Alamuddin is now Mrs George Clooney. Amal is a Lebanese Barrister. Elusive Fifth-Estate agent, Julian Assange is among her clients. A new version of Fairley and Allison’s The Monocled Mutineer was republished 1915 by Souvenir Press. Curiously, there had always been something a rivalry between Attallah’s Quartet Books and Ernest Hecht’s Souvenir Press – beginning when activist and author Ros de Lanerolle moved from across from Souvenir to Attallah’s Women’s Press in the early 1980s.

4 Fairley also worked on the equally controversial, Johnny Go Home: The Murder of Billy Two Tone (1975) with John Willis and Michael Deakin. Like The Monocled Mutineer, Red Under the Bed and Scotch on the Rocks this groundbreaking, prize-winning documentary has never been repeated on British Television. As a result of the show — which was very nearly banned at the last minute — the Conservatives heaped pressure on Wilson’s Labour Government to hold a Public Inquiry into the circumstances surrounding events covered in the documentary. A book was subsequently published by Quartet and Futura written by the show’s chief reporters, Michael Deakin and John Willis. The book focused on the hostels run by paedophile Roger Gleaves, who was duly convicted of assaults on boys as a result of investigations conducted during the course of work on the programme. During the early 1960s, Gleaves had been founder of ‘Greater Britain’, a patriotic pressure group formed under the auspices of League of Empire Loyalists (led by Arthur K. Chesterton of the British Union of Fascists). Curiously, Baron Ted Willis — the father of the documentary’s chief investigator, John Willis — had been an active anti-Fascist in his youth, serving first as Chairman of the Labour League of Youth and then Secretary General of the Young Communist League. Although supporting the Soviet’s nonagression pact with Germany in 1939, Ted Willis enlisted when Germany declared war on Russia and was enrolled into the Army Kinematograph Service — a propaganda unit attached to the Ministry of Information not unlike the IRD. The Army Kinematograph Service (known as ‘Number One Aks’) was put together by Russophile director, Thorold Dickinson to make high quality propaganda films. Dickinson had previously been busy at the London Film Society promoting Soviet directors Eisenstein and Dziga. Actor Peter Ustinov was another drafted in to the Army Kinematograph Service. His father was Jona ‘Klopp’ Ustinov, a White Russia émigré. Mi5’s principal science officer, Peter Wright would subsequently make the claim that Klopp Ustinov had worked for Mi5 under the codename, U35, and was handled by ‘Fifth Man’ suspect, Guy Liddell. The Army Kinematograph Service HQ was based at Curzon Street House, Mayfair which is where Mi5 had their technical services departments (1-4 Curzon Street).

5 Durham and Radgick were both thanked in the first imprint of Fairley and Allison’s The Monocled Mutineer for their “great forbearance extended over a long period of time”. The Joint Services School for Linguists that Durham attended was headed-up Commander David H. Maitland-Makgill-Crichton with teaching support from White Russian General, Prince Valentin Volkonsky (a Tolstoy relative) and Ukrainian Oleg Grigory Kravchenko. Suspected Russian Spy, Dorothy Galton played an administrative role at the school. Galton’s Mi5 file (KV2 3050) shows soy chiefs had grave concerns that Galton would compile a list of names from those completing courses at the school, which the KGB might then use as part of their recruitment process.

More reading

How the FO waged Secret Propaganda war in Britain, The Observer, Fletcher, 1978, Jan 29

Ghosting, Jennie Erdal, 2005

Ricky, Ricky Tomlinson, 2002

Heartbeat and Beyond: Memoirs of 50 Years of Yorkshire Television, John Fairley and Graham Ironside, 2017

Pickets Terror Squad Put Behind Bars, Daily Mirror 20 December 1973, p.7