A 157-page PDF book of this story can be found here

Among the masses of articles and books on the Jewish origins of Jay Gatsby, by far the most popular evidence that gets cited on a regular basis relates to Gatsby’s small, flat-nosed friend and mentor Meyer Wolfsheim — ‘the man who fixed the World Series in 1919’. [1] His depiction in the novel is also (and probably not unfairly) used to offer proof of the author’s casual anti-Semitism.

Biographers and critics are generally in agreement that Fitzgerald’s Wolfsheim was based on Broadway mobster, Arnold Rothstein, the son of an immigrant family whose forebears had been forced to escape the vicious spate of pogroms being carried out by the Tsarist regime in Bessabaria in Southern Russia during the late 1840s and 1850s. By the mid-1920s Rothstein was being hailed the ‘Moses of Jewish Gangsters’ — his work with the American Communist Party’s, Maurice L. Malkin helping preserve Communist control of the American clothing unions. Competing for control of the unions was Morris Sigman, another Bessarabian who at that time was serving as President of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. Believing that the activities of the American Communists were being driven by purely Soviet interests and belligerent ‘anti-capitalist’ mischief, the Socialist, Morris Sigman was making a bold and concerted effort to weed out as many Communist members as he could from the ranks of the union executive. Yes, Arnold Rothstein was a big-stakes gambler and bootlegger, but he was also a powerful figure in city and union affairs, providing the kind of muscle that could maintain stability and production within New York’s fractious clothing industry. He could be both the architect of chaos and the arbiter of peace. Judged along more Platonic lines and it might be possible to say that this charming, snub-nosed villain was the unacceptable truth of modern-day America. As David Pietrusza explains in his 2003 biography, Rothstein emerged from the swamp of criminal New York to become the great ‘go-between’. If politicians needed the support of vice lords, Rothstein was their man: “he made things happen and without fuss”. And more importantly, he never left any trail of evidence.

Given the ease with which Fitzgerald could stitch together multiple thematic threads and then tug them into life with lively contemporary references, the mysterious calls that Gatsby receives from Boston, Chicago and Philadelphia may well have been a thinly disguised allusion to emerging union tensions breaking out in those two key trade union districts at the time that Scott was writing the novel (the three cities are also where the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union had their headquarters). [2] Cast your eyes over the news columns of the period and you’ll see that Rothstein and his men were at the centre of a labour racketeering scandal in each of the three cities mentioned in the book. However, the mobster and his cronies were just as formidable in the bootlegging trade as they were in labour racketeering, and the handful of allusions to these cities could reflect either of Gatsby’s crime concerns. Gatsby’s love rival Tom Buchanan certainly seems to think it’s the latter: “I picked him for a bootlegger the first time I saw him, and I wasn’t far wrong’, he roars at one point. [3]

What we do know is that when Scott Fitzgerald was first sketching out plans for The Great Gatsby in the autumn of 1922, Philadelphia’s Prohibition chief, Senator William C. McConnell and the city’s Head of Secret Service, Matthew F. Griffin, were being investigated by Special Agent Frank J. Wilson for corrupt relations with the city’s bootleggers. Fitzgerald had also addressed the twin menace of illegal liquor and civil unrest in his short-story May Day, which depicts drunken, chaotic violence breaking out between the city’s Socialists and anti-Socialists at the annual worker’s parade. The author, like others, perceived an intricate relationship developing between organised civil lawlessness, organised crime, organised labour and bootleg liquor. Men like Rothstein provided the brains. The hooch provided the fuel. As Scott writes in his story, the “poets of the conquering people” were gathering in the provinces to drink “the wine of excitement”. It was a time of riotous prosperity — just not for everyone.

Listen the podcast now at audible.co.uk

Gatsby and Wolfshiem. Gerlach and Rothstein

At this point it may be worth reminding ourselves that it was the elusive Max von Gerlach — or Max Stork as he was better known in his youth — who had provided the most likely source material for Gatsby’s more lurid dimensions. He had his charm, he had his mannerisms and like Gatsby he had his dark side: the classic devil with the face of an angel.

Some ten months after being arrested for shooting dead his baby brother, it appears that the 15 year-old Max may have been involved in some worker skirmishes taking place in Brooklyn. According to the New York Times of November 3rd 1900, six speakers of the Socialist Labour Party had been whipping up crowds between Seventh Street and Avenue C on the East Side of Manhattan. As the crowd grew ever more threatening, it is believed that officers had drawn their batons and started clubbing back at the fractious troublemakers. A riot soon broke out and before long, six men had been arrested, among them a young Max Stork. The men were only in the cells a short time before they went back to their party headquarters at 98 Avenue C where another crowd of supporters had begun to gather waving red flags and jeering the Tammany-controlled patrolmen. [4] If it’s the same Max Stork (and there doesn’t appear to have been another man by that name in the district), then the incident would have occurred just ten months after accidentally shooting dead his baby brother in Yonkers. Had the 15 year old Max somehow been roped in as ‘thug for hire’? As provocateur, even? In actual fact, it may not be as far-fetched as it sounds. In the months that followed the 1919 May Day investigations, new information started coming to light which suggested that agents acting on behalf of the National Security League and the Department of Justice had been among those inciting the violence. They were also said to have been among the most vicious of the protesters in the right-wing counter demonstrations that followed. Rothstein wasn’t the first villain to use his power and influence to first call and then settle unlawful strikes. Workplace sabotage had gone on for years, and this was no less true of counter-sabotage. Government agents were commonplace.

Another of the men arrested alongside Max that day was Irving Herman Weisberger. A lifelong Socialist, Weisberger was some ten years older than Max and living at East 72 Street Upper East Side at the time the riot took place. Twelve months prior to his arrest Weisberger had had a letter published in the Marxist journal, The People, critical of Humpy Hanover, a Tammany ‘heeler’ and Mayor of Avenue C who kept a tight rein on the district police. Daniel de Leon, an influential Socialist with firm links to Russian anarchist and ‘Paris bomb plotter’, Boris Reinstein was running against the 16th Assembly ticket against Tammany man, Samuel Prince. At the time the arrests took place, Prince and his Tammany wirepullers had been determined to shut down de Leon and the ‘anarchist’ front. If this is not the same Max Stork then it’s remarkable that Max, his brother Alfred and his mother Elizabeth should end up living just 35-feet away from Weisberger on East 72nd Street in the US Census of 1910. [5] World Series gangster Arnold Rothstein, who had cut his teeth supporting Tammany leaders ‘Big Tim’ Sullivan and the gambler, George Considine, would be just a mile or so north of the pair at East 93rd Street.

Not a great deal is known about Max’s exploits and adventures in the period between the death of his baby brother in January 1900 and his exit from the US army in 1919, and what we do know doesn’t reflect on Max at all favourably. Some five years after the incident with the gun, Max was arrested for burglary in Yonkers. On that occasion he gave his name as Max Novak, using the maiden name of his mother. The New York Tribune described a fairly chaotic and ungainly scene. A youth had traded blows with a woman as he attempted to rob a shop belonging to Fannie Altman. The nineteen year old Max is believed to have entered the shop on the pretence of making a purchase. As the woman went to fetch something from the back of the shop, Max is said to have leapt behind the counter, opened the cash register and tried to make off with around $5 in cash. However, before Max could make it out of the shop the woman grabbed him by the coat collar. As he struggled to break free of her grip, Max assaulted her. A passing fireman by the name of Edward Fitzgerald is believed to have intervened and restrained him until Police arrived. The Sergeant who arrived on the scene would later tell reporters that he thought the boy had been involved in several other neighbourhood thefts. The 19 year old, still living at the family’s 144 Herriot Street address, later gave his name as Max Albert Stovak, a chauffeur in the employ of car dealers, John J. Walsh and Frederick Pardee Fuller of 71 South Broadway. Fuller, a respected member of the Psi U fraternity, had like his father, initially trained as a lawyer before investing all his money in cars. In 1905, Fuller had caused no small amount of sensation when he launched the luxury four cylinder model, ‘The Ardsley’ . His grandfather was George Fuller, a Presbyterian congressman and newspaper owner from Connecticut who claimed direct descent from one of the original Mayflower settlers.

Shortly after his encounter with Mrs Altman, Max moved to Manhattan. Here he got the job of chauffeuring around the dubious Broadway and gambling impresario, John H. Springer, manager of the Grand Opera House. Before long, the pair were involved in a collision featuring Springer’s brand new $12,000 French touring car on West 23rd Street. The car, which had been carrying Springer and his entire family at the time, had burst into flames as it smashed between two cabs. Luckily for Stork, he and the Springers had made it out of the car and were out on the street at the time that it exploded. According to the press, the car had literally been torn to pieces. Gasoline had then leaked from a broken tank and the whole thing had gone up in smoke. The family were treated for concussion and superficial injuries but no lasting damage was done. [6]

It was, incidentally, Springer’s second near fatal collision in a very short space of time, the previous one happening almost one year before to the day. On that occasion the impresario had gone berserk. He just flipped. When handed a ticket by a local traffic cop, the usually cool and unflappable Springer yelled at the policeman that he would “have his head chopped off for this”. Appearing in court, Stork accused the cab men who caused the second smash of acting “little better than anarchists and murderers”. [7] If it is the same Max Stork who was arrested as a Socialist during the worker skirmishes in Avenue C in Brooklyn, then the reference to ‘anarchists’ is an interesting one, as it suggests some specific grievance against the group.

For Springer, it was business as usual. But it wasn’t just his cars that got him trouble, it was his racy theatre productions too. In January 1913, responding to what he perceived to be the impossible demands of the censors, Springer headed to Berlin to produce a series of performances there. As Max is also believed to have been in Germany around this time, it may be the two trips were somehow related. Shortly after losing money in a theatre house there, Springer filed for bankruptcy, citing an unprofitable series of “lemon plays” from his booking company, Klaw and Erlanger, for the theatre’s dire fortunes. In addition to his gambling and theatre interests, Springer was also the owner of the Empire State Garage near East Seventy Fifth Street. In 1909 one of his touring cars ferrying eight passengers to a house party in New Jersey had ended up in a ditch. Nobody was badly hurt but its driver was charged with speeding. [8] Max’s home on Second Avenue would have been little more than a ten-minute walk from the incident.

Max Marries into the Mob

It may have been through his work with Springer or Colonel Cushman Rice that Max came into contact with Marie R. Lovell, the footloose Socialite daughter of racing millionaire, William Lovell, a Liverpool-born bookmaker with a “shady reputation” who had immigrated first to Australia and then to the United States after amassing a fairly considerable fortune in mining. [9] Like Springer, Lovell was not without baggage. In the summer of 1877, a warrant had been issued for his arrest and that of gambling partner, James B. Kelly. The order for Lovell’s arrest had come from Judge Hoffman in New Jersey as the district began to get tough on a virulent pool-selling racket that was then operating with impunity in New York. Law reports from Hudson County describe how Lovell had been charged with publicly organising lotteries known as Auction pools, French pools and Combination pools which he later deposited at the Jerome Racecourses in New York. Lovell was fined $800 and ordered to pay the full legal costs. [10] Just three years later another arrest warrant would be issued, this time for Lovell’s son who was reported to have absconded with over $5,000 in diamonds from his stepmother. It seems that three previous terms in prison on Blackwell’s Island had done little to curb the young man’s vices. [11]

A regular face on the race rigging circuit being run by Peter De Lacy and Tammany Hall leader ‘Boss Croker’, William Lovell would also serve for a time as Vice President of the Jockey Club in Coney Island in Brooklyn. This would almost certainly have placed him in the orbit of Tammany grandees like August Belmont Snr and August Belmont Jnr. [12] The Belmonts were powerful men of means, both financially and politically. In years to come the pair would feature prominently in the life of gangster, Arnold Rothstein — ‘Meyer Wolfshiem’ in the novel. [13] Rothstein and the Belmonts would each become prominent figures in the running of the club at Coney. In terms of his both his personal and criminal history this puts Gerlach roughly in the orbit of Arnold Rothstein.

By 1908, Max Gerlach, still going by his regular name, Max Stork, had married Lovell’s daughter Marie in Manhattan. A report in the New York Sun in May revealed that the 22 year old ‘importer’ had known Miss Lovell for a long time and that they would sail by the Red Star Line to honeymoon in Belgium. Lovell’s previous marriage to John D.B. Dunbar had ended in disaster when she discovered that he already had a wife and five children living in Flushing. The extent of the deception didn’t end there as Dunbar had also made away with $20,000 of Lovell’s savings. Despite being heiress to a $150,000 fortune, her marriage to Stork can’t have been a smooth one as on the 1911 census Max can be seen back living with his mother Elizabeth (Novek Stork) and stepfather Thomas J. Reilly in Upper Manhattan. Max’s wife meanwhile, was boarding at the home of George H. Oakley and his wife on Amity Street in Patchogue, Long Island. This put Lovell and her volatile brother Amos at Blue Point within just a few miles of Rothstein’s brand new pleasureland base at Long Beach.

Baroness von Stork

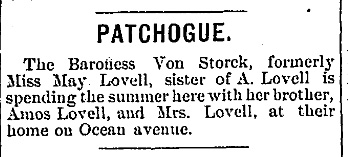

Max’s Gatsby-esque delusions of greatness must have been in force quite early in his life, as a local item in The Suffolk County’s Patchogue news column dated June 1909 proudly announces the arrival of ‘Baroness von Storck’ at the Ocean Avenue, the home of her brother Amos Lovell. It seems clear that for a time at least, Max Gerlach had adopted the entirely fabricated nobiliary particle ‘von’ for his Stork-Storck moniker. [18] But he wasn’t the only one in the family who was doing it. Just twelve months earlier the newspapers had been reporting that Max’s brother-in-law, Amos Lovell, appearing in court over a minor bootlegging offence, had instructed his lawyer, District Attorney, Ralph C. Greene to make it known that his grandfather was Lord Lovell of England. Amos explained how his mother had died recently leaving a $400,000 estate but that it was so tied-up that he couldn’t get access to a cent of it. He was indicted on two counts and held under $1000 cash bail. Eventually he got off with a $100 fine. [19] There had in actual fact been no formally recognised Lord Lovell for about four centuries. The last one had been a staunch supporter of King Richard III and Sir William Catesby. A closer look at the archives reveals that the family had forfeited its title after the defeat of Richard by Henry Tudor after the War of the Roses. After the Battle of Stoke Field, Lord Lovell disappeared and his remains have never been found. The name had since become the stuff of ballads and legends. On a more sinister note, when acting as manager of the Oceanic Inn in Red Bank, New Jersey, Max’s brother-in-law Amos had been implicated in a murder inquiry connected with the sale of illegal liquor. [20]

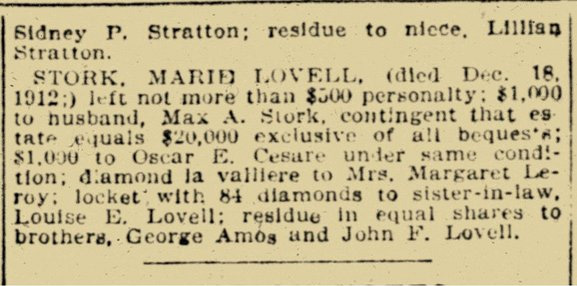

On December 18th 1912 Marie Lovell Stork died at the home of her neighbour, Belle Carman. The 29 year old woman’s will reveals that she left a modest sum of money to her estranged husband Max, who was by this time doing quite well for himself on the car racing circuit. [14] In light of Stork’s ‘rum running’ credentials, the next bit makes an interesting footnote. According to the 1920 census, Carman’s nephew, Harry Thompson had been working as a government employee off the Long Island ‘Rum Coast’ as part of the New York City Coast Guard. [15] A Wills and Probate notice in the New York Times dated January 10 1913 reads: “STORK, MARIE LOVELL (died Dec. 18, 1912) left not more than $500 personalty: $1,000 to husband Max A. Stork, contingent that estate equals $20,000 exclusive of all bequests.” Some items of jewellery were left to her siblings and another $1000 to the Swedish American caricaturist and wartime propagandist, Oscar E. Cesare. Cesare would have an extraordinary career by any standards. In October 1922, he would find fame as one of the only American artists to gain entry to the Kremlin building in Moscow where he was invited to produce sketches of Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky. [16] The sketches, together with a fascinating and very candid account of his meeting with Lenin in Moscow, would be published by the New York Times on Christmas Eve, 1922. Oscar had immigrated to America from London in 1894. By 1900 he was living at Alexandra Place in Buffalo, little more than a thirty-minutes’ walk from Scott Fitzgerald and his parents, Edward and Mary on Summer Street and Elmwood Avenue.

Interestingly, Cesare’s trip to Russia had been arranged as part of the American Famine Relief expedition organized by Herbert Hoover and overseen by Gerlach’s ‘old friend’, Cushman Rice. Cesare and Mrs William Henry Chamberlain had been seconded for three months to the American Committee for the Relief of Russian Children, then under the management of Captain Paxton Hibben (a friend of John Dos Passos, a friend of Scott) and the Near East Relief organization. It was their job to check and report on the distribution of supplies. Although critical of Hoover, and sceptical of his abilities to ensure successful distribution of the aid, Hibben’s special relief effort for children had no other option but to operate under the direction of his Congress-backed A.R.A. The arrangement probably went a little like this: in return for the full cooperation of the Russian Government in getting the goods distributed to all those genuinely in need, Cesare’s series of sketches would show Lenin and other leading Soviets in a more favourable, human light. [17] Either way, it’s intriguing to think that Gerlach’s friends Oscar Cesare and Cushman Rice together with Scott’s brother-in-law, Newman Smith all enjoyed close dealings with relief efforts in Russia and Eastern Europe under Hoover’s sanction. However, it may yet transpire that Max himself may have been far more interested in redirecting the odd consignment of grain, barley, yeast and sugar bound for the starving peoples of Europe to the no less needy colony of illegal distillers and brewers back home. Prohibition had created an altogether different kind of famine. Hoover was unlikely to care either way. He’d never been a strong proponent of the law in the first place. And if his illicit shipping activities in Russia in July 1919 were anything to go by, Hoover wasn’t averse to playing fast and loose with the hold.

Merchant on Broadway. Elections in Havana

Professor Kruse’s research into Max’s life has uncovered many intriguing details, but perhaps none more so than an East Side street address he mentions. The address is one that is listed in the 1910 edition of Trow’s General Directory where it lists Max A. Stork (Gerlach) as a merchant with a business at 99 Second Avenue in Manhattan’s Ukrainian Village. [21] Max would have shared the building with 44 year old Austrian, Rosie Shoenberg, President of the Rachel Richter Lodge, a Jewish benevolent association. Several years later the same address would be used to host meetings for the Manhattan Eighth Assembly of the Jewish Socialist Federation of America. There’s no evidence to suggest that Gerlach was Jewish. A look at his family in Germany makes this terrifically unlikely. Even so, according to the Jewish Communal Register, its branch Secretary, Minnie Sussman would hold meetings from the premises (possibly ‘The Second Avenue Theatre’ or an earlier Yiddish theatre) every Wednesday evening. [22] The organisation’s HQ was at 175 East Broadway under Secretary Max E. Lulow and treasurer Jacob B. Salutsky, better known as J. B. S. Hardman, a Russian born Socialist activist who had found himself Editor of the New World Weekly at 175 East Broadway. Critical of the American Communist movement, Salutsky would make a number of attempts to bring his group, the Committee for a Third International under the banner of the Communist International of Russia. The Bolshevik supporters, the Jewish Socialist Verbund would also host meetings at this theatre. At the time that young Max was roaring his engine around the streets of New York, Manhattan’s Second Avenue was the entertainment area of the Yiddish quarter. With its eclectic hub of theatres, restaurants, cafes and clubs, the district would come to be known more colloquially as the ‘Yiddish Broadway’ and featured prominently in the route taken by legendary anarchist Emma Goldman and her partner, Alexander Berkman. The Café Monopole at 144 Second Avenue (Veselka today) was even a favourite haunt of Leon Trotsky during his pre-Revolution trip to New York. [23] In 1920 , Max’s half-brother Alfred Stork and his wife Alice can be found living in an apartment with their son Alfred in an apartment at 1341 Third Avenue. The same address had previously been used by anarchists, Frank Abarno and Carmine Carbone, the members of the Bresci Circle who were charged with planting a bomb in St. Patricks Cathedral, NYC on March 2, 1915 (it failed to detonate). Emma Goldman, who had friends in the Bresci Circle, helped raise funds for the pair’s defence. As Agent Grunewald was investigating Goldman at the time he questioned Max in June 1917, its possible that he or his brother, Alfred, had had contact with the group. At one point in the novel, Gatsby’s friend Nick Carraway remarks that he would “have accepted without question” the idea that this elegant young rough neck may have sprung from the Lower East Side of New York. Well this was the Lower East Side of New York. And just like Gatsby he had “drifted cooly out of nowhere”.

Whatever business Max von Gerlach did have in the area, there’s little denying that it was a thriving and prodigious district for the passionate young radicals of East Village. Both the Socialist Party of America and the Allied Hebrew Citizen’s League had based HQs at 99 and 122 Second Avenue. The site was popular with the Irish too. Since the early 1900s, 99 Second Avenue had practically been the second home of Tammany Hall speakers like Edward E. McCall, who would use the venue to rally the support of German voters for the Democrat vote.

Much of the speculation about Max’s activities in Professor Kruse’s ground-breaking archaeology focuses on his frequent trips between Cuba and Berlin under the alias Max Stork. Whilst there is no firm evidence that has so far come to light that would prove that the trips that Max made between 1915 and 1918 were part of some illegal, mobster enterprise or some clandestine mission for the US military, it does seem very plausible that his adventures in Cuba at least had arisen as a result of his friendship with Cushman Rice, the very rich and very mysterious mercenary from Minnesota who had made Cuba, the ‘Sugar Empire’, his second home. But even if the nature of these trips remains difficult to pin down, the timing of them is certainly curious.

In November 1916, a very crucial and controversial General Election had taken place that had left Cubans fiercely divided. Liberals started screaming that the whole thing had been a fix, that the election had been stolen from them. It was said that even the sitting President’s people had been preparing for defeat. In scenes not totally dissimilar to those we saw on Capitol Hill in January 2021, a blistering counter-movement led by José Gomez began to take shape. Within weeks there was civil-war. American interest in the whole affair was intense. War with Germany had reduced sugar production in Europe to a disturbing all-time low. Buoyed-up by US investors like Colonel Rice, Cuba started quadrupling its production. Suddenly it was sugar that was going to decide the war, making it the target of a complex chain of foreign intrigues. Civil war was creating a vacuum drawing in all kinds of opportunists. The neutrality that the country’s serving President, Mario Menocal had so far managed to preserve would now be tested.

In March 1917, the American press reported on the breaking up of a German spy ring that had been operating between Mexico, Cuba, and Germany. It was alleged that German agent provocateurs were intending to foment rebellion among revolutionaries in Cuba and Mexico and blow up the Alvear Canal, the main water-supply in Havana. Two Germans had already been arrested, one of them known to be a close friend of rebel-leader, José Gomez, the main contender in the alleged revolt. The press had an even more sensational claim to make; one of the other men arrested was believed to be a member of an exclusive Chicago Club and maintained a “luxurious apartment” in the city. As a way of gaining leverage over key political and financial players, the man was said to have ingratiated himself with a large brokerage house with offices in Chicago and New York. The reports described how a number of American detectives were known to be in Cuba mingling with revolutionaries in an attempt to get to the bottom of an organisation that was being referred to as The Iron Cross. [24] A short time later, Walter T. Scheele, the American President of the New Jersey Agricultural and Chemical Company was arrested on suspicion of pro-German work and conspiring to set fire to munitions ships operating between Havana and Europe. Within days, President Menocal was announcing Cuba’s entry on the side of the Allies into the war. America had pledged to go in, and Cuba would now be joining them. President Woodrow Wilson immediately cabled a message to the Cuban President describing his deep satisfaction that the people of Cuba had come out to defend the rights and liberties of “all humanity”. [25]

In March 1918 there was one final dramatic development. A special cable had been received by the New York Times informing them that Otto Riners, the former American Consul in Cuba had committed suicide. The dispatch explained that the former consul been accused of being a German Spy. [26] Whether Colonel Cushman Rice, generally regarded as a bit of a ‘our man in Havana’ figure, or his young protégé Max Gerlach had played any part in providing intelligence that had led directly or indirectly to the smashing of the ring (or even complicity in the ring) may well be the stuff of fantasy, but the timing of the various trips the pair made during this period is certainly curious.

According to his US army application, Gerlach’s own activities in Cuba dated back to 1906 and 1908 when he alleges to have been racing cars and opening a garage for the Winton Motor Carriage Company in Havana. In 1921, Z.W. Davis, the millionaire director of the garage, would be arrested by Federal Agents as part of a major investigation into stolen bonds and securities said to be worth in excess of over $8,000,000.

Strangely enough, the years 1906-1907 also covered the period in which Cuban Liberal party had staged the first of its ten year power grabs. As the government of its President Tomás Palma began to collapse, America’s President Roosevelt sent in US troops to restore some balance and protect lucrative American interests. Among those making arrests and communicating via long secret cipher messages to President Roosevelt directly was Gerlach’s 1914 passport provider, Major James A. Ryan who had complete control of the Havana Police. News reports in September 1907 described how Captain Ryan had rounded-up and detained three senior Cuban Generals along with twenty-four other rebels and charged them with conspiracy. Over in Camaguey was Gerlach’s 1918 and 1919 sponsor Colonel Rice, where, according to signals picked-up by the MID, some 2000 new English rifles had been heading to support the insurrection. Just a few months prior to this, Frank G. Carpenter, Special Correspondent of the Washington Star, had caught up with a very relaxed Colonel Rice at his ‘quaint’ Camaguey ranch. During the interview ‘Cush’ Rice cheerfully talked-up the prospects in Cuba for American cattle farmers. A little time later he was back in New York buying a brand new racing car. Just when an uprising was being feared in Camaguey, stock farmers had flooded the market with cattle, driving beef prices down as much as 30 per cent. Cushman, incidentally, was among several prominent cattle buyers profiting handsomely from the rumours.

The claims made in Gerlach’s 1919 application do however, contradict reports in newspapers that he was in the employ of John H. Springer at a garage in New York during the 1906-1907 period. It is of course entirely possible that Gerlach had, like Colonel Rice, been shuttling between New York, Mexico City and Havana on a regular basis, perhaps on the pretext of business or racing concerns.

The FBI’s interest in Max begins in June 1917, shortly after America entered the war and trouble had started brewing in Cuba. By his own admission, Colonel Cushman A. Rice, the man who provided Gerlach with his personal recommendation, had been a confidant of Filipino Revolutionary, Emilio Aguinaldo and been busy putting his ear to the ground on plans for Independence. Cushman’s experience of matters in Cuba ran significantly deeper, but there is no definitive account of his movements during this period that I have been able to uncover as yet.

The Man Who Fixed the 1919 World Series

Professor Kruse’s research into Max’s life has uncovered many intriguing details. The scope for espionage and intrigue is, you can imagine, quite immense, but what the exact nature of Max’s relationship was to Colonel Rice is something that can only ever be guessed at. It certainly wasn’t unknown for resourceful young crooks like Gerlach to be hired on a casual basis by the MID and the American Secret Service. Such men were confident, self-possessed, well-connected and more than capable of handling themselves in a crisis. As long as they were able to provide ballast to domestic and foreign objectives, the power and reach of members of organized crime had always been greeted with no small amount of tolerance, and perhaps even with a pinch of respect. What we do know is that each of the three referees that featured on Max’s 1919 passport application — Cushman A. Rice, George Young Bauchle and Aaron J. Levy — had either strong or casual links to notorious World Series gangster, Arnold Rothstein, making the much speculated link between Gatsby, Max Gerlach, the 1919 World Series and Rothstein as plausible as it is fascinating.

If you’ve seen the film or read the book you may recall a scene in which Gatsby and Nick Carraway make their way across Queensboro Bridge and into New York. Gatsby has an old friend that he would like to introduce to Nick. Arriving at noon in a basement restaurant on West 42nd Street, the three men meet for lunch in a private ante-room of the bar. The Times Square district of New York is where the real Arnold Rothstein conducted business and this is the place we meet his fictional equivalent, Meyer Wolfsheim. Wolfshiem is dining alone when Gatsby joins him. The gangster looks up at the ceiling and remarks on a pair of sea nymphs painted on it. He orders some high balls and the three of them sit and talk.

The bar they meet in is likely to be based partly on George Considine’s ‘New’ Hotel Metropole on 43rd Street and the ‘Old’ Metropole Hotel on 42nd Street. The latter was a swanky Tammany-era saloon whose dimly-lit backroom was popular with New York’s sporting figures and muckraking journalists. Rothstein and Considines had been among a handful of investors in Coney Island’s fantasy amusement park, Dreamland and had run a series of regular poker games here in the early 1900s. The bar had an ornate mural and tall, coffered ceiling with frescoes. In December 1906, it was the location of a meeting between New York’s unflappable crime-busting DA, William Travers Jerome and the Metropole’s poolroom emperor, George Considine. According to The New York Times, Considine had led Jerome to a quiet back room and divulged some of the secrets of his rival bookmakers.

The story that Wolfshiem regales them with as they dine is a true one, even if the location has been switched. In 1912, the notorious Times Square gambler and club owner Herman Rosenthal decided to take a stand against corrupt New York Police Officer, Lieutenant Charles Becker, generally assumed to be managing the more seedy affairs of the Tammany Hall. Rosenthal had refused to be brought into his schemes and was gunned down in front of astonished customers in the café of the ‘New’ Metropole on 43rd Street. In his nostalgic yet confused reverie, Wolfshiem (or rather Scott) has switched the locations around: he meets Gatsby and Nick in what bears a much greater resemblance to the Old Metropole on 42nd Street. The New Metropole on 43rd Street is where the real Rosy Rosenthal was gunned down. In Scott’s novel the three of them have literally gone back in time: they sit in the old time ante-room of a gambler’s den on 42nd Street talking about a murder that took place at its new location on 43rd Street. “Four of the men were electrocuted”, remembers Nick. “Five, with Becker”, adds Wolfshiem. And electrocuted they were. He may have switched locations but the outcome was just the same. The men responsible for murdering Rosenthal were also executed in real life. [27] The time-switch could either be a genuine mistake on Scott’s part or a clever little attempt to repeat the past through comingling old world and new world events. The neatness of the design is easy to overlook; here we have three men discussing the past in a bar that no longer exists, talking about part-real and part-invented people being shot in a future version of the same bar that has been moved around the corner. The spatial and temporal fabric of this world is all confused. Scott has created a parallel universe in which past and future collide.

The idea of an alternate reality had first been introduced by Scott’s hero, H.G Wells in his novel, Men Like Gods and had been more comically explored in his Gatsby hors d’oeuvre, The Vegetable. First serialized in America in Hearsts International Magazine in November 1922, Well’s Nietzschean fantasy contemplated what it would be like to have two dimensional universes “lying side by side like sheets of paper” in a many-dimensional space. A place where men could experience “a roughly parallel movement” through time and space, “universes, parallel to one another, and resembling each other, nearly but not exactly.”

When a somewhat woozy Nick Carraway relates an out of body experience in the second chapter of the novel, is he expressing his sense of dislocation with his immediate situation or describing a brief encounter with a disorientating mirror universe?: “I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.” The terms he uses — within and without — are likely to have been borrowed from the quasi-esoteric philosophies of the time, when self-styled Vedic mystics like George Gurdjieff were teaching the young bohemians of Paris and New York how to penetrate the wall of illusion that prevented us from experiencing and enjoying paradox in a world of multiple dimensions. Like Well’s Men Like Gods it is a study in plurality. What we get in the scene at the Hotel Metropole is a cross-pollinated world of both the frightfully real and the hopelessly romantic. It is a scene that is rich in nostalgia, and the time-switch would make perfect sense: it is a New York that is full of contradictions and full of ghosts.

As the three of them continue talking, Nick notices a pair of ivory cufflinks that Wolfshiem is wearing. “Finest specimens of human molars,’ he informs Nick. When Wolfshiem leaves he asks Gatsby if the gentleman was a dentist. “Meyer Wolfsheim? No he’s a gambler. He’s the man who fixed the World’s Series back in 1919.” Nick is palpably shocked and asks why he isn’t in jail? “ They can’t get him, Old Sport. He’s a smart man.” The penny has finally dropped. Nick is finally prepared to believe that all the rumours about Gatsby are true.

The story’s historical resonance continues in a later chapter, when we learn that Walter Chase, a gambling friend of Tom Buchanan had been ‘left in the lurch’ by Wolfshiem and Gatsby. The character’s real-life equivalent is probably Hal Chase, the baseball player, friendly with gangsters and gamblers alike, who was indicted for the role he was suspected of having played in fixing the 1919 World Series. The opinion of the press was that Chase and other players had been framed and double-crossed by Rothstein and his men after taking $40, 000 in ‘safe bets’. Corrupt police chief, Big Bill Devery, Chase’s former boss at the Yankees, had been an influential figure at Tammany Hall for years under Richard Croker. By aligning himself with Chase, the reader can only conclude that Daisy’s polo-playing husband had his own circle of dubious characters around him. He’s not only a thug, he’s also a hypocrite.

Did Scott Fitzgerald meet Arnold Rothstein?

To date, any plausible connection between Scott and the Broadway mobster has usually been put down to legend and the work of an overactive imagination. But there may be a little bit more to it than that. As Scott sat down to work on his last unfinished novel, The Last Tycoon in 1937, he dashed off a letter to fellow writer Corey Ford at MGM. Scott’s letter talks about the challenges the two men faced as screenwriters in Hollywood. Two things were occupying his mind about the movies at this time: the hold that the Mob retained over Hollywood, and the increasing dominance of Communists in studio unions. As a result of the stifling combination of members-only attitudes coming at them from all sides, few of their friends had succeeded here. Dos Passos had “nibbled”, and Erskine Caldwell appeared to have ‘got in’. It was a pretty “unsatisfactory business” all round, wrote Scott, saying that he understood how simple it would be to be a Communist under these conditions,“being able to explain away the worlds inadequacies” in a single swipe. Unlike at Gatsby’s, Hollywood was a party that didn’t admit anybody who hadn’t been invited. It was a closed-shop. Scott then went on to explain that he was working on his next “selective” novel, confessing that he had deliberately excluded the more salacious real life elements of life in Great Neck to give the novel its haunted, ethereal feel. All of the “ordinary material” he’d experienced at Long Island, “the big crooks, adultery themes” had all been toned down to suit the novel’s poetic intentions. The next one would be similar in tone, but like his first novel This Side of Paradise, it would be a little more “comprehensive”. There would be more in the way of background and historical content, more detail.

The next thing he shared with Ford was a little more intriguing. One of the many bizarre events that Scott hadn’t left out of the Gatsby novel had been his “own meeting with Arnold Rothstein”. Scott explained that it had been one of those “small, focal points” that had “impressed” him whilst at Great Neck. If what Scott was telling Ford was true, then the scene in the novel in which Nick meets Meyer Wolfshiem had actually been based on Scott’s real-life encounter with the man who fixed the 1919 World Series: Arnold ‘The Brain’ Rothstein. Scott hadn’t minded sharing this fact because Ford had liked the novel so much. He was aware he was being candid. [28] But how did this meeting come about? Who, among Scott’s friends and colleagues, was the one who introduced the pair?

If you were to look over the cast-list of Scott’s friends in Great Neck there are two possibilities that really stand out: the sports journalist Ring Lardner, a close-friend and neighbour whose name featured prominently in coverage of the World Series scandal, and gentleman bootlegger, Max Gerlach. The former would have been well acquainted with the back-room of the Considine bar on West 42nd Street, whilst Gerlach would have been the better match where liquor was concerned. The report into Gerlach’s arrest at the Speakeasy he was managing on West 58th Street claimed that it was Rothstein who owned the property. If this is true, then it is quite possible that the imaginary scene in the novel when Nick is introduced to Meyer Wolfshiem by his handsome young protégé, Gatsby could have its roots in a real-life ‘mirror’ meeting between Gerlach, Rothstein and Fitzgerald. Was it possible, on the otherhand, that a situation had arisen that would pool the talents of all these men: Cushman Rice, Arnold Rothstein, Max Gerlach and Ring Lardner? Chicago journalist Lardner had enjoyed especially close relations with the White Sox, and had provided several important leads, insights and suspicions into the 1919 World Series scandal in which Rothstein was alleged to have paid eight members of the Chicago White of throwing the game against the Cincinnati Reds. The tip-offs and information that Ring would receive during this period would be syndicated across America’s press columns.

In the inquiry and trial that followed, Ring would also be called as witness. Scott’s friend had played an influential role in exposing the fix and was left feeling bitter about the whole affair. To him, baseball had offered one of the purest and most simple of dreams and the team that he loved had let him down. Lardner would later write that there had been something prophetic about the scandal. The events of 1919 had ushered in a decade of unprecedented crime, corruption and immorality: “Say it ain’t so Joe … say it ain’t so. It had been like the last desperate plea for itself.” [29] It’s easy to see why Scott included references to the scandal in the novel and why it had become something of a “small focal point” for his observations on the death of the American dream. Contrary to what you might think, however, it wasn’t a game that Scott liked especially, viewing it as a game for boys played by a “few dozen illiterates” and “bounded by walls” that removed any real sense of danger or adventure. What he did get though, was the part that baseball played in the psyche of the American nation and how very precious it had been to his friend. Scott was a little bit more philosophical than Ring: the enclosure of the ball park was both an escape route and a prison. Its rules were there to be broken.

A completely fresh find in the newspaper archives may shed some additional light on the matter. The story dates back to 1915 when Max von Gerlach’s army and passport pal, Colonel Cushman Rice was still in Cuba and the infamous 1919 World Series scandal was still some four years away. The story starts as most of the best stories do, with another story. In April 1915 a Pennsylvania newspaper was reporting that a whopping $27, 000 was being offered for the ‘twin brother’ of a lucky penny that was believed to have secured a sensational World Series triumph for Boston Braves chief, George Stallings. The man who was making this remarkable offer was Yankees owner, Captain Tillinghast Huston. The man who claimed he had the penny but was firmly rejecting the offer was Gerlach’s friend, Colonel Cushman Rice who was described by the story’s reporter as the “foremost American in Cuba”. Frustratingly for Huston, as long as Colonel Rice was the owner of the penny, the irascible old adventurer said he had no intention of handing it over. As far as Rice was concerned, whilst the penny was in his possession he had full control over the outcome of the championship.

The next claim that Huston made was more astonishing still. These weren’t just any pennies. They were magic pennies. According to the story that Huston told the newspaper, the pennies had been taken from the neck of a “Cuban negro” killed during Cuba’s escalating race wars. He claimed the small, shiny pair of pennies had been in a little bag along with a number of “hoodoo” items, including charms. He had given one of the pennies to Stalling to bring him luck at the World Series. The next thing he divulged was no less intriguing; the man who Huston was hoping to buy the penny for was Wild Bill Donovan. [30] Huston told the reporter that he and Donovan were “old pals” and he would have done “almost anything” to get his hands on that penny. [31]

Just four years later the same Wild Bill Donovan would find himself at the centre of the Black Sox scandal, the 1919 World Series game that gangster, Arnold Rothstein (Meyer Wolfshiem in the book) would be accused of rigging. As President of the National Sporting Club in Havana, Colonel Cushman carried some weight in several gaming areas, so the six degrees of separation linking him to Rothstein were hardly surprising. At the end of the World Series, Donovan, now manager of the Chicago White Sox and ten of his players stood before a grand jury accused of throwing the game in a complex, wide-ranging deal organised by Arnold Rothstein and George Young Bauchle’s gambling syndicate. According to witnesses, Donovan had learned of the teams’ decision to throw the game some time beforehand. [32] Although cleared by the jury, his new boss William F. Baker, owner of the Philadelphia Phillies owner would later sack him. Donovan was replaced, of all people, by ‘Kaiser Wilhelm’ (Irving Key Wilhelm).

The decision to throw the game is believed to have arisen during a disagreement with club owner, Charles Comiskey. When his players threatened to strike, the Tammany Hall strongman refused to pay their wages. Trouble had been brewing since September the previous year when the Boston Red Sox had threatened to strike during the remaining games of the 1918 World Series. On that occasion, the League’s Ban Johnson, a little worse for the booze, had decried the threat as ‘Bolsheviki’. It was a case of Red Sox, Red Scare. Rothstein’s newspaper friend, Harold Swope, used this disastrous near-miss as part of a bid to have Ban Johnson removed permanently as President of the League. Writing in the Evening World in December that year, Hugh S. Fullerton said that baseball now needed a peace conference almost as much as Europe did. A claim was being made that Johnson, in a state of war-era panic, had bungled and mismanaged the League. His failure to give the demands of the Red Sox players a fair hearing and for refusing to allow the Cleveland players to attend the Labour Day Series, was creating the kind of turbulence that could easily destroy the game. For the sake of the game Johnson had to quit. As Kevin Coster’s heroically sentimental movie would later make clear, baseball wasn’t just a game for many Americans. The crudely sketched diamond of dirt, dust and grass that made up the typical ballpark was the vigorous field of dreams upon which the corn of America’s greatness would grow. As far as the pundit John B. Foster was concerned, baseball shouldn’t be hampered by secret organizations claiming to represent the interests of the players. Writing as the First Revolution was taking place in Russia, Foster laid-out his belief that Baseball was not a business but a “clean, honest and open sport” that should be played with the fiercest sense of rivalry. It was an honourable and ennobling discipline. The sense of fraternity and brotherhood that was beginning to enter the game was increasingly being seen as “foreign, hostile and injurious to the sport”. There was way too much handshaking going on for Foster’s liking.

The fact that Rothstein never faced trial makes one wonder if the whole scheme had been devised to deal with the threat posed by striking players and to close down the various economic and ideological threats to America being presented by militant unionism on the ballpark. When the time had come to pay the players, Rothstein reneged on the deal. In an attempt to get their money the players went public. As a result, the authorities had little option but to prosecute them, and Rothstein just walked away. [33] The plight of the striking players had been dealt the heftiest of blows as public support for the strikes collapsed.

A few years later, tragedy would strike again when the disgraced former White Sox manager, Wild Bill Donovan was killed in a horrific train accident in Forsyth, New York. Donovan had been travelling in the observation car (the rear carriage) of the train when another train had ploughed into the back of it. His own train had been forced to stop when a car had stalled on the railroad crossing. The driver and the passengers had been forced to escape and could only watch as the carnage unfolded. All of those travelling in the observation car were killed on impact. [34] Donovan, who also died instantly, appears not to have been carrying the lucky Cuban penny that day.

That Arnold Rothstein and Colonel Cushman Rice occupied the same social and gambling spheres is supported by a story told by journalist Arthur ‘Bugs’ Baer in the 1940s in which Rothstein and Rice both feature. The story told by Baer takes place on the evening of Election Night in 1916, an election that would prove to be dominated by fears over a Mexican Revolution and America’s entry into World War One. Woodrow Wilson had defeated Hughes and Cushman Rice and Arnold Rothstein had made their way to the Waldorf Hotel bar on 34th Street. It was here at the Waldorf that ‘Bugs’ Baer claimed ‘Cap’ Rice had taken over “thirty-five thousand smackers” off the bookies that night after betting on Woodrow Wilson to pull off his bid for the White House. Rice’s lucky streak had extended so far as running Rothstein out of chips. Baer confessed that he never did get to know how Cap Rice had made his fortune, “he was a fellow who bobbed up at all big fights, World Series, conventions and Kentucky races. You would meet him in London, Mexico, New Orleans or any spot where you could stick a pin. I always thought he was government agent but I never knew for certain.” [35]

Was Rice a government agent? It’s certainly an interesting statement, especially in light of Rice’s easy familiarity with Rothstein and the power the Broadway mobster would be asked to exert over America’s striking workers, but if there is the faintest credibility of Max being involved in Socialist politics (most likely as an agent provocateur or errand boy), then the next story involving Rothstein and the Russian-American Trading Corporation, means it could all get murkier still.

Un-American Activities

This story takes us back to the investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities heard at Congress House in the late 1930s, but first we need to rewind a little bit further and go back to the claim made by Maurice L. Malkin of the American Communist Party. Malkin had claimed that during the US General Strike of 1926 he had been instrumental in hiring Arnold Rothstein to bolster the efforts of the furriers union, who were at this time broadly under the control of the American Communist Party. In order to create the right kind of impact for the press Malkin had wanted Rothstein and his boys needed to bring the city to a standstill. For this, huge volumes of workers would be required to flood the streets. To ensure the stunt ran successfully, and that the workers weren’t removed from the streets as quickly as they arrived, Malkin also required the cooperation of the New York City Police. This meant buying off the office of Police Commissioner McLaughlin in addition to several other precincts including Fifth Street, Charles Street, West 30th Street, Clinton Street and 47th Street. The heads of the New York Industrial Squad, Jesse Joseph and Barney Rudevitzky were also bought off too, receiving $45,000 and $50, 000 respectively. Out of the $3,500, 00 raised for the strike over $110,000 of Rothstein’s money had gone into paying off police. Much of the remainder was skimmed off by various individuals by falsifying receipts. [36] The men acting as bag men for the $150, 000 loan were Malkin’s attorneys, Abraham Goodman and the Russian-born Judge, Leonard A. Snitkin. Rothstein would provide the initial cash-input and the repayment of the loan would be guaranteed by AMTORG, the Russian-American Trading Corporation, which had opened its first American offices at 136 Liberty Street and 165 Broadway in June 1924. [37]

Managing the corporation’s affairs in Britain was ARCOS chief, Philip J. Rabinovitch who had relocated to London from New York sometime in 1919. Rabinovitch was supported in his US efforts by a series of AMTORG presidents, Isiah J. Hoorgin (aka. Isaj Churgin), Paul J. Ziev, Alexis Y. Prigarin and Saul Bron.[38] Hoorgin was killed in a boating accident in the Catskills district of New York in August 1925 and Prigarin resigned for personal reasons less than twelve months after being appointed.[40]

During his cross examination by Congress in 1939, American Communist leader Malkin is clear about one thing: Rothstein had been driven by money, not by politics. Rothstein was no cadre; he was a cash-cow who had no apparent interest in the nobler aims of Communism at all. It was just a question of how much profit he could make on the interest once the loan had been made. [41] Rothstein had assumed a similar dispassionate role in the 1912 garment strikes when he provided muscle and funds to the garment strike force and unions of 1911 and 1912. In Baku, the city’s wirepullers had Stalin. In New York they had Rothstein.

Malkin’s attorney, Leonard A. Snitkin was a different proposition altogether. The Russian-born former Justice Chief had been embroiled in one radical escapade after another, from draft evasion schemes, to eviction evasion schemes. Like his legal associate Aaron J. Levy — the man who provided the draft-board reference for Gatsby’s bootlegger twin, Max von Gerlach — Snitkin had been a key member of the Tammany Hall executive. In 1901 Snitkin and several other Tammany figures had been pulled up and charged with illegal vote rigging practises. Officials alleged that he and the group had been using fake registrations among immigrants on the Lower East Side to boost their standing at the polls. This wasn’t the first time that Snitkin and Rothstein had crossed paths either. In 1923, ‘bucket shop’ operators Edward M. Fuller and W. Frank McGee hired Snitkin during a probe into the finances of city broker, Charles A. Stoneham, owner of the New York Giants baseball team and one of several men who had stood to benefit handsomely from the Black Sox World Series scandal. As the cops closed in, Fuller, who had been embroiled in a number of criminal schemes over the years under several different aliases, had been hiding out at the home of Arnold Rothstein in the days leading up to his arrest. It was later discovered that Rothstein had been dipping into Fuller’s funds to the tune of $425,000. Investigators suspected the pair of being complicit in fixing the 1919 World Series but were never able to prove it.

It’s at this point that films like Oliver Stone’s JFK generally crowbar in some totally unnatural kind of recap into the script, largely on account of the dizzying array of characters and the unreasonable demands placed upon the viewer to follow and make sense of an impossibly complex mesh of motives and scenarios. A similar approach is needed now, because it was during the period in which Rothstein’s friend Edward Fuller was being investigated over his bucket shop and World Series activities that Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald made the decision to up sticks from White Bear Lake and take up residence at 6 Gateway Drive, quite close to where Fuller had an estate. [43] It’s something that’s been mentioned by several biographers already, some speculating that the parties thrown by Fuller may even have inspired the ones we see in the Gatsby novel. The evidence for this though is thin on the ground. Fuller wasn’t particularly well known for his parties and there was absolutely nothing of Jay Gatsby about him. Nevertheless, there are a number of authors who place him tantalisingly close to the author and his wife in Great Neck. But in terms of an Oliver Stone-style mid-movie recap I’d like to begin to pull the various strings together; and for this I’d like to hold in your mind Arnold Rothstein, Scott’s relationship with Max von Gerlach and the whole thing with Fuller going on in court just as Scott arrives in Great Neck and starts sketching out the outline of the book that would eventually become The Great Gatsby.

The period that we are looking at is October 1922. Scott has set up his writing base close to his World Series friend Ring Lardner and their sometime employer, the newspaper man Herbert Bayard Swope — editor of the New York World. It is here that Scott will begin to observe the “big crooks” of Long Island and be introduced, at some point or other, to Arnold Rothstein, a long-time friend of Swope and his wife Pearl, whose illustrious dinner parties Scott, Ring and Zelda would occasionally attend. Things were hotting up for Rothstein. May 1923 would see the first mentions of Rothstein’s name in relation to the Fuller case. A witness had come forward with proof that the former gambler had paid Fuller and McGee’s $25,000 bail bonds and America was about to wake to the full derisible scope of the 1919 World Series Scandal. Just 24 hours before Gerlach scrawled his message to Scott saying he was “enroute” back from the coast, the Department of Justice were beginning to share their fears for the safety of missing witness, Ernest Eidlitz who had been accused by Rothstein’s lawyers of stealing documents on behalf of William Randolph Hearst and his newspapers. They believed the ‘all round scoundrel’ Eidlitz had been cooking up a case against them in collusion with the State Attorney’s Office. A statement made by prominent racing man, Colonel Samuel L. James had accused Arnold of attempting to pay-off Eidlitz on James and Fuller’s behalf. Rothstein, Fuller and McGee denied all knowledge of this. There was no going back at this point: Rothstein’s name was now in regular circulation.

Clean Books, Immoral Measures

At the time that Gerlach was leaving his message saying he would be dropping in from the coast, Scott had just been putting the finishing touches to Absolution, a dark and unsettling story that the author had originally intended using as a preface to Gatsby. His frustration with the Catholic faith of his youth had entered a new and thoroughly unforgiving phase. The note that Max would leave had been scribbled over a newspaper item captioned ‘The Beautiful and Damned’. Beneath the headline was a picture of Scott, Zelda and the two-year old Scotty posing on the lawn of their home. The Warner Bros ‘photo play’ version of the novel had been released in January and was still doing the rounds in theatres.

The summer of 1923 had found the 27 year old author in an irascible, intolerant mood. Money was a constant struggle and America couldn’t modernise quickly enough. Scott wanted to push forward in huge, artistic leaps. He felt that American literature was on the threshold of something great but that the default conservatism of its social elites were holding it back; the nation’s rocket thrusters were icing up and his race to the stars had failed to lift-off. In his ledger Scott records that this was the most miserable year he had had since the age of nineteen. In January the author had learned of the death of his friend, Prince Val Engalitcheff (an apparent suicide) and by July he was hard at work on the first (and only) production of his play The Vegetable. Things began to improve in the second half of the year. His 18-month year old daughter Scotty had learned to talk and Zelda’s sister Rosalind had arrived. Scott was meeting one challenge after another, and they weren’t just confined to the distractions of everyday life in Great Neck. The world of publishing was under attack from a whole new menace: a demand for greater censorship.

A letter that Scott had written to the editor of The Literary Digest in April reveals his deep frustration with New York censoring laws: “The clean-book bill will be one of the most immoral measures ever adopted. It will throw American art back into the junk heap where it rested comfortably between the Civil War and the World War”. Scott couldn’t understand how a book like Simon Called Peter, a popular novel openly critical of Catholicism, could pass the censors and not books by more powerful and deserving authors like Theodore Dreiser and James Branch Cabell. [44] There was little or no sense of justice in the world. The heroes of the war had vanished. Faced with an uncertain future in an uncertain world, America had handed a battery of extra powers to its instruments of law and order. Men were jailed and books were seized. The surface of the world was cracking and the past was slipping away. Anyone found to be letting go of the rope and letting the past drift idly away on the electric current that was then coursing up the Hudson and through all the five boroughs of New York was classed as outlaw, Fitz included. Editors like Margaret C. Anderson and authors like James Joyce were becoming the bewildered new faces of the criminal underground, obliged to flee to Paris simply to preserve their freedom and continue their art. The running of illegal ideas started shuttling between the bays in cases that were every bit as illicit as those holding rum: there were bootleggers and there were bookleggers. Scott had been contemplating moving across to the publishers Boni & Liveright but had been quick in acknowledging that there were “curious advantages” for radical writers like himself to be published by “ultra-conservative houses” like his present one, Scribner’s.

The Cotillo-Jesse Clean Book Bill that Scott refers to in his letter to the Litereary Digest had just been passed by the New York Assembly. Within days it was being presented to a specially prepared Senate hearing. John S. Sumner of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice did all the running on it, personally placing in the hands of the Senate Committee a half-dozen sealed envelopes which he alleged contained evidence of some serious obscenities. [45] The opposition objected on the basis that it was impossible to judge a book based on a selection of paragraphs taken out of context. Among those who raised their objections at the hearing was Horace Liveright, the publisher behind Theodore Dreiser and his friend and legal adviser, Joseph G. Robin. The sponsors of the Bill were Justice John Ford and Martin Conboy Jnr, President of the New York Catholic Club and a powerful Irish-American ally of Scott’s mentor, Shane Leslie (now serving as Chamberlain to the Pope) and Shane’s father-in-law, William Bourke-Cockran. [46] Conboy Jnr had come out with all guns blazing against the publication of Joyce’s Ulysses. His reasons were twofold: the first was that he loathed the casual obscenity used by so-called ‘artists’ and the second was that the book’s ‘Cyclops’ scene featured a brutal caricature of Arthur Griffiths, a close personal and political associate of Conboy’s friend (and legal client), the Irish Republican leader, Éamon de Valera.

Adding additional weight to the Bill was the Italian-born Senator, Salvatore Cotillo, the East Harlem Democrat who had been decorated by Italy for the work he had carried out on behalf of President Woodrow Wilson during the war. Cotillo returned to Italy as envoy in 1923, hoping to strike a deal with Pope Pius and Mussolini to help stem the flow of immigrants to America. The request had met with some resistance from Mussolini, who believed that if America were to pass the new and much tighter immigration bill, less money would be sent back to Italy by relatives working in the United States. This would mean fresh woes for an already struggling economy. Cotillo had returned to America in the spring of 1923 with a number of vague concessions. In Italy he had told the press that once he returned to the States he would do everything in his power to make America more tolerant of Fascism and to promote Mussolini as a noble and commanding leader “of the highest order”. Cotillo wished to press home the idea that the Duce of Italy was not only legitimate but also credible. Contrary to what many Americans had been thinking, Fascism was not mere “brigandage” but a “lawful and strong government, full of patriotic ardour.” [47] However, back in America the Senator was quick to downplay this sentiment, insisting that Fascism in America was not only something to be resisted but something that could never work. Cotillo faced the challenge of striking a very delicate balance. There were multiple parallel concerns to consider, and various stakeholders to please. Rome was now a vital ally in the war against ‘godless’ Russian Bolshevism. And also quite possibly, the silent and uncompromising partner in the war on obscenity.

Whilst in Rome, Cotillo had a series of private meetings with the newly coronated, Pope Pius XI who duly assigned Bishop Michele Cerratti to assist with the Senator’s request. [48] The official word on Cotillo’s visit was that he was here to ease the tensions between the supporters of Mussolini in the Italian communities of New York and the anti-Fascist movement that was swelling among the city’s Communists and Socialists. Unofficially he was there to score their cooperation as part of a solution to an urgent immigration crisis under the banner of criminal exploitation. Italians who feared prosecution and persecution in Fascist Italy were now turning up on its shores in droves, bringing with them the bloody, relentless feuds that Italy had become world-famous for.

Was it possible there was a link between Cotillo’s mission on Immigration and his fairly unexpected support of the Clean Book Bill? The three main sponsors of the Bill, John Ford, Martin Conboy and Senator Cotillo were certainly all Catholics. As the senate hearing reached its climax, Justice Ford brought out a raft of religious and patriotic groups. The Catholics were among those most strongly represented with the Holy Name Society, the League of Catholic Women, the Knights of Columbus and the Federated Catholic Societies all coming forward to share their views. The Roman Catholic Church had always taken a fairly liberal view of alcohol and prohibition but its generous attitude to booze didn’t always extend to modern literature and contraception — both of which were regarded as the totally unnecessary evil of fashionably liberal democracies.

Sex was turning up everywhere, and everywhere more and more people were getting comfortable with it. 1922 had witnessed the birth of the latex condom. The old Comstock Law still prohibited its promotion, but the public demand was insatiable. Practically everybody was now able to pick up a ‘Prophylactic’ cheaply at any drugstore. The bland and inoffensive rubber sheath, which had long been associated with promiscuity and adultery, was condemned with the utmost ferocity by the Church in Rome. No matter where you looked in America at this time there was a crisis. The unholy trinity of booze, books and bottoms was wreaking havoc with America’s crumbling moral fabric. Worse still, the undue influence of a climate of quid pro quo, certainly in regard to America’s unhealthy reliance on the cooperation of the Fascists in Italy and the provision of a suitable resolution to the Irish Question, was tearing it apart still further. If Nick really had looked up at the moon in Gatsby’s garden that year, he would have seen that the sky was falling.

Was it Gerlach who introduced Scott to Rothstein?

The fantasy I have in my head is that when Scott did finally open the door to Max Gerlach, probably with a pair of Whisky Sours clinking in his hand, he had just that minute finished reading James Joyce’s Ulysses. On the table next to it would sit The Satyricon by Petronius, freshly re-translated and published by Albert Boni and Horace Liveright, the two main nemeses of the Clean Books League. Just as he hears someone knocking at the door, Scott would be skipping to the infamous Trimalchio ‘banquet’ scenes of the book— one of the latest works of fiction to fall victim to the New York censors. In my own little fantasy scenario, Gerlach would be familiar with the book and toss out a few quotes as he stepped through the door. “To think that wine has a longer life than man, Old Sport”, Gerlach would quip as he glides through the porch and into the hall, glancing around to see if his host had company. “While there’s still life in the wine let’s fill our glasses. Slaves are men, my friends. Even if hard luck has kept them down, they should join us in drinking this water of freedom!”

In his tipsy and carefree state, it would probably have been quite easy for Scott to equate the gaudy and irreverent nouveau-riche slave created by Petronius with smooth-talking villains like Gerlach and Rothstein — Princes and Kings among the rulebreakers of Long Island. The two men’s gutsy disregard for authority and their wily dry-witted elegance would, to anybody who didn’t know better, probably have had a bit of a Wild West charm about it. Like the glamourous raw men that a young James Gatz would encounter around the ports of the Barbary Coast, Scott might have thought he was being presented with a pioneer debauchee who had “brought back to the Eastern seaboard the savage violence of the frontier brothel and saloon.” Meeting Rothstein is likely to have been no less thrilling. Men like these were living what Nietzsche only preached. Here was a snub-nosed, tough-talking Superman that existed beyond the usual conventions and orthodoxies of society. There is no small amount of irony in knowing that it was Rothstein’s money that went into producing the spectacular Dreamland amusement park at Coney Island. It may have been ex-Senator William H. Reynolds who bagged all the credit but it was Rothstein who had both the magic and the capital to make it happen. The 15 acre plot at Surf Avenue overwhelmed its visitors with a dazzling display of lights and chaotic noise, before gently and very gorgeously depriving them of their hard-earned cash. Here was a man who was as capable of creating the darkness, as he was of lighting it. Zarathustra had come down from the mountain with the news that America as we knew it was dead. And for a while at least, men like Gerlach and Rothstein might have seemed quite impressive. Heroic even.

At the beginning of 1923 Scott had been having a tough time focusing his energies into work. Since his arrival in October, Great Neck had just been one long party, with Ring Lardner and himself getting ‘stewed’ on a regular basis. The couple had been completely bewitched by the sheer volume of the town’s celebrities: Frank Craven, Herbert Swope, Mae Murray, Fontayne Fox and Samuel Goldwyn, to name just a few. Even General Pershing, another vague associate of Max von Gerlach, had been an entertaining enough distraction after the “dull healthy middle west’. There’s no actual telling how close Scott’s house was to Rothstein’s friend, Edward M. Fuller, or how much Scott knew of the investigation into his bucket shop activities, but if his 1937 letter to Corey Ford at MGM bragging about his meeting with Rothstein is anything to go by, he certainly wasn’t unfamiliar with the Great Neck crooks. Of course, getting stewed on a regular basis meant getting liquor on a regular basis and this itself would have brought him into contact with some of Long Island’s more undesirable (or more resourceful) characters, Max Gerlach among them. Living beyond your means on this lavish scale often meant living beyond the law.

It is certainly curious to note that Max von Gerlach’s 42 Broadway address at this time was also within just a few yards of Edward M. Fuller & Co at 50 Broadway. In November that year, the same 42 Broadway address would feature in another ‘bucket shop’ investigation, this time with fatal consequences when 33 year old broker, Jesse A. Wasserman, a key witness in the case, committed suicide at his home in New York. It is believed that Wasserman had shot himself through the head in the bathtub at his home on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Several letters from his wife Carla von Bergen in Baden, Germany were found alongside his almost fully-submerged body in the tub. Two suicide notes were discovered, one addressed to his wife and the other to The Lotos Club, a New York Gentlemen’s Club that had been formed to promote the more liberal concerns of journalists, actors, singers, writers and artists. In January that year, Wasserman had attended a Lotos Club dinner. Among its speakers was Otto Kahn, the owner of the mock-Gothic ‘Oheka Castle’ which movie director Baz Luhrmann would use in 2012 as the basis for Gatsby’s mansion. During the speech Kahn renewed his vows to America: more and more it was “a land of high striving” made up of a magical, winning compound of “sentiment and idealism”. Even in its most materialistic days “the power of the idea and the impulse of the ideal” had been proven to have had a far greater influence over the spirit of the nation than its famous green crinkly dollar. America’s most valuable asset had always been the imagination of its people. Kahn called upon the artists of New York to help educate its soul to help awaken in its people the love and understanding of “all that was beautiful and inspiring”. Beneath the nation’s crudeness, its newness, “its strident jangle and its jazziness” was the rich, raw grist of a great culture. All that was really needed to ignite that latent talent was a spark. It wasn’t a man of unlimited wealth that America needed right now but a man of unlimited imagination and poetry. Kahn’s “land of unlimited possibilities” was in desperate need of its prince, someone whose “capacity for wonder” was even greater than even his love and control of the dollar. What America needed right now was someone like Jay Gatsby.

Kahn’s speech that evening had been ably backed-up by the Scottish soprano, Mary Garden, making her debut speech at the gala as the club’s first female member. The singer talked of her love of Jazz and her even greater love of breaking the rules. Had he attended, Scott would probably have been rattling his cutlery in boisterous agreement. Tinkling his glass more modestly beside him, would be Jay Gatsby, the patron saint of all dreamers. The previous year, Jesse Wasserman, a long-time patron of Kahn’s club, had featured as witnesses in the ‘draft-dodging’ Grover Bergdoll scandal. Bergdoll had been hard-drinking, womanizing racing car driver and aviator who had somehow managed to dodge being drafted into the army. A worldwide manhunt ensued and Bergdoll was eventually traced to Germany. [50]

During the court case that followed the arrest of Scott’s neighbour, Edward M. Fuller in February 1923, it was disclosed that the swindler had received cheques totalling nearly $200,000 from Arnold Rothstein. These cheques were dated between November 10th 1920 and Nov 9th 1920, certainly years before Scott arrived on the scene. The judge investigating the bucket shop practices admitted that he was unable to fathom the mystery of Rothstein’s connection with Fuller’s firm, despite Rothstein being one of the known sureties behind Fuller & Company. [51] The various links between New York baseball owner Charles A. Stoneham and Arnold Rothstein were even stronger, the gangster having brokered the deal that saw Stoneham pick up the Chicago and New York Giants just months ahead of the 1919 World Series. [52] There were also plausible links between Stoneham and Cushman A. Rice, Stoneham having opened the first racetrack and casino — the Casino Nacional — in Havana with Giants manager, John J. McGraw. [53]

By and by, the interests of both the track and the Jockey Club were sucked into the Cuban National Syndicate. There was another thing too. The 99 2nd Avenue address that Max Gerlach used to conduct his business affairs in 1910 was little more than twenty-feet away from the law firm of Fuller’s legal counsel, Leonard A. Snitkin in Manhattan’s Eighth Assembly. It had been Snitkin’s legal colleague, Aaron J. Levy who, like Cushman Rice and George Young Bauchle, had supported Gerlach in his application to enlist with the US Army. [54] As Rothstein biographer David Pietrusza points out in his Life and Times account of the World Series criminal genius, Judge Levy’s position as majority leader of the New York State Assembly, and his graduation to the bench at the Supreme Court was to prove critical in protecting Rothstein’s gambling clubs. Levy was Arnold’s go-to man at the courthouse, and regarded by most as the man who fixed-up the charges against Lieutenant Charles Becker in the Herman ‘Rosy’ Rosenthal murder case, clearing Rothstein and his men of any suspected involvement in his death. [55]