Benzion Netanyahu, father of Binyamin Netanyahu served as chief aide and secretary to Ukrainian defence organizer, Vladimir Zeev Jabotinsky, the leader of the rightwing Revisionist breed of Zionism, precursor to the now-ruling Likud party. This essay explores the role played by the 1905 Revolution in the creation of a Jewish Homeland in Palestine.

The energetic Ukrainian, Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky arrived in Saint Petersburg sometime between the end of 1903 and the beginning of 1904. The account of his arrival in his 1936 autobiography, The Story of My Life is a little vague on the details. He begins his story by saying that he arrived in the Russian capital standing at the thresholds of two very distinct worlds: the world of literature and the world of Zionism. His attendance at the Sixth Zionist Congress in Basel at the last few weeks of summer that year, had hardly come about by design. Whilst his commitment to the self-defence militia organised under the watchful eyes of Ukrainian figurehead, Meir Dizengoff and Dr Henrik Shaevich, had never been much in doubt, the young Odessan’s knowledge of Zionism at this stage in his life, amounted to little more than a few well-thumbed books by Theodor Herzl, Leon Pinsker and Moshe Lilienblum. [1] The books had been loaned to him by Shlomo Saltzman, an Odessan businessman that Jabotinsky had known from the city theatre’s Italian Opera. Jabotinsky had been recruited to run the defence group’s HQ in Moldavanka, an impoverished industrial suburb of Odessa. A poster on the wall of the office, quickly assuaged any doubts or fears they may have had, reminding them that he who killed in self-defence was free from punishment. Within weeks the young writer had become an indispensable member of the group, driving around Odessa, often for days at a time, collecting donations and negotiating the sale of arms with local gun shop owners with the assistance of Kishinev-born businessman Meir Dizengoff, an ex-member of the Narodnaya Volya who had joined the Hovevei Zion movement upon his release from prison.

After several months of uninterrupted service, Jabotinsky began to wonder why none of the group’s activities — no matter how indiscreetly performed — had failed to come to the attention of the Police. It was a mystery no more when he was introduced to the owner of their office: it was a Tsarist agent, Henrik Shaevich, the man who had the job of neutralising the threat posed by the Jewish Bund and steering the common Jewish worker away from the revolutionary activities of the Left.

At this stage in his life, Jabotinsky’s political energies had been poured into a fairly unruly mélange of Socialist Democratic and Liberal newspapers and journals, including contributions under the alias ‘V. Zhabotinsky’ to Peter Struve’s illegal publication Osvobozhdenie (something that has only just revealed after a fresh review of the first drafts of Jabotinsky’s autobiography). If it wasn’t for the dramatic scenes that he had witnessed in Kishinev as part of the relief program organised by Dr Shapiro and his employers, the Odesskie Novosti in 1903, it is entirely likely that Jabotinsky would have chosen the creative path to glory. As a response to the passion he had shown for his work in rehabilitating the region in the aftermath of the massacre he was personally approached by Saltzman to represent the Zionist group Eretz Israel at the upcoming congress in August 1903, just a few short months after the massacre in Kishinev. A crucial vote was taking place on whether to back a British scheme to set-up a Jewish National Homeland in East Africa — under a British protectorate — or persevere with the ideal of a full-scale ‘Return to Zion’, the Land of Israel.

As part of his preparations for the Congress, Jabotinsky sought the council and approval of mutual friend, the Socialist Revolutionary, Vsevolod Lebedintsev, whose nonconformist intellectualism and adventurism became ever more attractive as options became limited and the violence to Jews increased. Whether or not he had already been sold on ‘propaganda of the deed’, remains uncertain. Jabotinsky had always despised the impulsive, reactionary energy of the anarchists, but the harrowing scenes he had witnessed in Kishinev were clearly having a profound and life-changing impact. Once in Saint Petersburg he would set about writing a translation of In the City of Slaughter— a hard-hitting epic poem describing the aftermath of the Kishinev massacre from the pen and the blood of his hero, Hayim Bialik:

“Behold on tree, on stone, on fence, on mural clay,

The spattered blood and dried brains of the dead.

Proceed thence to the ruins, the split walls reach,

Where wider grows the hollow, and greater grows the breach;

A short time he left for the Congress in Basel”

— The City of Slaughter, Hayim Bialik [2]

Shortly before embarking on the long journey to Basel in Switzerland, Jabotinsky composed a letter to an author who had shown a good deal of interest in his own work as a writer. The author was Maxim Gorky, the titan of Russian literature who would play such a crucial role in the escape of future Zionist leader, Pinchas Rutenberg and revolutionary Russian Orthodox priest, Georgy Gapon on the afternoon and evening of Russia’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ Revolution on January 22 1905. It was on this day that the Tsar’s Imperial Guard opened-fire on hundreds of unarmed and peaceful demonstrators led by the well-meaning priest. In the aftermath of the blood-bath, Gorky had given refuge to Gapon and Rutenberg as they made plans to leave the country. The events that day would change the course of Russian history forever. Jabotinsky’s decision to send the letter was clearly the manifestation of a jangling bag of nerves and apprehension about such a dramatic shift in direction, and the pressure that was inevitably bearing down on the young man’s shoulders as a result of such a last minute request by Solomon Saltzman. It was the usual thing; a reflex action. Presented with a sudden and bewildering shower of uncertainties, new people and new situations, Jabotinsky did what any young man would do in the circumstances, he made an instinctive grasp for the comfort of the things he knew and a possible — and very dynamic — escape route.

Addressing Gorky by his Christian names, Alexei Maximovich, he said that he was sending him a collection of various ‘feuilletons’ he’d previously had published in newspapers — a ragbag mixture of criticism, poems and reviews. Aware that Gorky was now enjoying an executive position at the Znanie publishing house in Saint Petersburg, the young Ukrainian said he was submitting them for consideration as a collection or anthology. [3] He was worried that because of the collection’s origin in journalism they would become doomed to obscurity. Jabotinsky felt that it his failure to move away from the press was stifling the great promise he had shown as a serious writer. And what’s more, his closest friends agreed. He was, however sure that there was much energy and true venom in some of several of the items he was submitting. It may be possible to infer two things from the tone and the timing of his letter to Gorky: the pair had been in communication quite recently and that Gorky was among a circle of admirers who thought he may have been wasting his energies on the press. Jabotinsky’s persistence must have paid off, because shortly after arriving in St Petersburg after a post-Congress trip to Rome, one of his best efforts — Poor Charlotte — was published by Gorky’s publisher.

Written in 1902, Jabotinsky’s 15-page poem told the story of Charlotte Corday, executed by guillotine for the murder of rival radical leader, Jean-Paul Marat at the time of the French Revolution. Fearing the kind of direction that France might take under Marat and the violent reign of terror being unleashed in France by the Jacobins, Charlotte had pledged to kill him. In her words, she was killing one man to save a thousand. The removal of the monarchy, she concluded, could be brought by liberal and democratic methods. The Charlotte Corday of Jabotinsky’s poem is presented as a complex, pitiful challenger whose attempt on Marat’s life would clinch the celebrity and the glory that had so far eluded her in life. In one single violent act she seeks to elude the deep, burning melancholy of her existence “as barren as the wind.” It was an exercise in self-mythology. Like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s fictional creation, Jay Gatsby the heroine is seen crafting a successful image of herself — an artist in the studio adding brushstrokes to her life that facing death will give it meaning — using the victorious dreams of the rebels to weave the rich velvet lining of her own casket. Just as it is for the Jihadists of the 21st Century, the love of death in glory as presented in Poor Charlotte would almost certainly have served as encouragement and inspiration for the Jewish Defence leagues of Odessa. Such is the uniqueness of the insight offered in the poem that it may be fair to speculate that the 23-year-old Jabotinsky had fantasized about staging such a death himself, or if not for himself, then almost certainly recommending it as a noble course of action for the daring young insurgents under his command in Ukraine. At the height of the tensions between the Ottomans and Odessa’s Christian and Jewish neighbours in Macedonia, tales abounded of delirious Turkish Jihadis slaughtering thousands in pursuit of the glorious rewards and “eternal joys” that awaited them in heaven — not to mention the structure and relief it would bring to their meaningless lives. [4] The promises dangled in front of the disenfranchised masses were nothing new. In the last years of the 20th Century, Jabotinsky’s edifying potrayal of Corday’s actions would provide become the de facto motive for assassins Mark David Chapman (John Lennon) and John Hinckley Jr. (who shot but failed to kill President Ronald Reagan).

The poem’s heroine, suitably enough, couldn’t have been a more divisive figure and had probably been intended as the trigger for an explosion of discussion among Jewish revolutionaries. That the crucible in which the narrative was being forged showed Charlotte Corday in a vaguely sympathetic light should by rights have left the censors in a complicated position; on the one hand ‘Poor Charlotte’ had murdered a violent revolutionary in pursuit of more liberal and democratic solutions and on the other she was a merciless — and worryingly casual — assassin. Just two years later, Jabotinsky’s future ally, Pinchas Rutenberg would murderously dispose of his friend, Father Gapon in just as casual and murderous a fashion. Perhaps plans were already in place to make a similar kind of sacrifice.

Given the timing of the two events, it seems likely that galley proofs of Poor Charlotte had probably accompanied Jabotinsky’s pre-Congress letter to Gorky, because within months of his arrival in St Petersburg, over 2000 copies of the work had been printed and were ready for distribution. 3000 copies had been prepared but 800 copies of the book were duly confiscated when several officials of the Administration on Printing Matters turned up at Znanies offices whilst the press was still warm. Gorky had been warned of a crackdown by Tsarist officials by Shlomo Gepstein, an architect and journalist from the young poet’s hometown of Odessa. Gorky had put Gepstein in charge of publishing Poor Charlotte. Sadly, the censorship laws that existed in Russia at this time would practically ensure that the poem wouldn’t see light of day. Speaking to Joseph Schechtman at his home in Tel Aviv the 1950s, Gepstein says he had been the one who suggested to Gorky that they should have a large number of copies already printed and bound before they arrived at Znanie’s offices for approval by the censors in St Petersburg and to hold back a more significant number for distribution through other channels. [5] Additional support was offered by the pair’s fiercely loyal friend Shlomo Saltzman.

The story a fine, uplifting episode in Jabotinsky’s early life but it puts a big question mark over the young revolutionary’s claim that he only knew “two people” when he arrived in St Petersburg in the last few months of 1903. Gorky’s apartment at 20/16 Znamenskaya Street was little more than a ten-minute walk from the building on the Fontanka embankment where the meetings of the Zionists took place and the author’s enthusiasm for promoting for Jewish identify and culture was already significant at this time. Gorky may have been more popularly known as the master of Social Realism but it would also be fair to say that he was one of the great innovators of the Pogrom literary genre — his 1901 story ‘Pogram’ being among the very first of its kind. The story had been written in response to the horrific scenes that Gorky had witnessed in Nizhny Novgorod some fifteen years previously. The writer had been so deeply stirred by what he had seen that he became a firm and powerful opponent of anti-Semitism, helping to establish, among other things, the Russian Society for the Study of the Life of the Jews. Writing of Gorky’s philosemitism in his groundbreaking short-story, Professor Amelia Glaser remarks on how Gorky’s ‘passive’ Jewish characters revealed the sad, pervasive nature of Russian Christian hypocrisy. Gorky had recognised that the huge volumes of disenfranchised Jews could play a crucial ‘rhetorical’ role in the revolutionary movement and the end-of-century impulse towards change and social progress. [6]

The Yeast of Mankind

Gorky had discovered that a deeper and more profound grasp of tyranny and oppression could be experienced in the suffering refracted through the prism of Tsarist anti-Semitism that retarded the soul and culture of Russia. For Gorky, the Jews were the “powerful yeast of mankind.” They could always be relied upon to “elevate” the world’s spirit, “bringing new and stirring noble thoughts and calling forth new strivings after the better things.” [7] His views on Zionism had been a little more complicated. In regard to its core ideals, he had for the most part remained buoyant and optimistic: “I am told Zionism is a Utopia; I do not know, perhaps. But inasmuch as I see in this Utopia an unconquerable thirst for freedom, one for which the people will suffer, it is for me a reality. With all my heart I pray that the Jewish people, like the rest of humanity, may be given spiritual strength to labour for its dreams and to establish it in flesh and blood.” [8] The point that Gorky was making was pretty simple; these were not the ‘cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palace’ of Prospero’s Island, they were the ‘shaping fantasies’ that cooled the rootless, seething brains of the Jewish Diaspora. It was ambitious yes, but the dream they had was securely anchored in a practical objective; the provision of a series of ovular settlements in Palestine. The problem for Gorky lay in how the seed would take on the intractable land of a horribly divided Russia. To succeed, the whole project would need global support. The dream would need to be shared by a non-Jewish world. As Alan Levenson reflects in his 2002 essay on Gentile reception of Zionism, the ‘Selbstemanzipation’ pursued with waspish single-mindedness by the likes Leon Pinsker was not as absolute or as plausible a remedy as his followers had hoped. [9] The world would have to connect with Zionism in other ways. It would need narratives that it too could understand, stories that it could relate to; in reality, the distinction between Emancipation and Auto-Emancipation — in which Jews were in control of their own fate — were neither as clear or as useful as previously envisaged.[10] Gorky’s starting point was that the Jews and the proletariat had a common enemy. Speaking to Herzl’s flagship Zionist newspaper Die Welt shortly after the Kishinev massacre, Gorky and Leo Tolstoy reiterated their belief that atrocities like these were the direct result of “a policy of mendacity and violence pursued by the Russian Government.” The peasants involved in such explosions were “living in complete darkness.” They were literally goaded into acts of frenzy by a committed set of agitators, furthering the aims of the government. [11]

In an interview with Leon Rabinovich’s Russian Hebrew newspaper, Ha-Melitz in December 1902, Gorky had described how after attending a Zionist meeting in Nizhny Novgorod he had trouble accepting how the movement intended to earn the support and sympathy of the Russian people if they continued to refuse Christians as members. [12] Those attending the meeting had just returned from the First (and last) All-Russian Zionist Congress, authorized and coordinated by Zubatov and his team of ‘legals’ at the Hotel Paris in Minsk in 1902, where a proposal to admit Christians had been rejected. That same year Gorky had received the celebrated Zionist-artist Ephraim Lilien to his home, to work, or so it was believed, on an illustration for an anthology of Russian poetry provisionally entitled Sbornik. As enthusiastic and excited as Gorky was about Zionism, he clearly anticipated slow growth and traction among Liberals and Social Democrats unless they were able to cooperate with other movements. The likes of Gorky and Herzl sought to promote a policy of ‘cultivated philosemitism’ that would help prepare the groundwork for more ambitious endeavours. The diversity offered by the autonomous Congregationalist movement within the Christian Church offered one such route. What was required was a standard rejection of anti-Semitism and a belief that the Jewish Question was not some elusive Utopian dream but was rooted in a series of obtainable and practical resolutions. [13] Intentional or not, he was helping to promote a sense of “Jewish otherness.”

Looking at this some hundred years later it’s hard not to see how in Gorky’s resolve to pay tribute to the Jews he may have influenced the later Soviet and Fascist narratives that would attempt to portray all Jews as biologically and culturally predisposed to antagonistic and subversive activity: it was a double-edged sword, so to speak. The overly effusive Gorky, bubbling over with the giddy enthusiasm of a complete tourist was perhaps confusing the tireless energy that the Jews showed in confronting Tsarist oppression with some intuitive revolutionary instinct that was exclusive to their race. Instead of seeing a motor neurone response, Gorky was seeing a Double Helix. He had consecutively failed to see that the root of their reactionary natures lay not in their DNA but in a series of conditioned responses. It was reflex action — that was all. In responding to his natural writer’s impulse he had sought to romanticize the suffering of the Jews and politicize and aggrandize the crude, bloody racism that invariably gave rise to that suffering. What it needed was a significant paradigm shift. The culture in which prejudice continued to take root and hierarchies maintained would need to alter.

Alexei Suvorin Jnr’s ‘Palestine’

By 1904 Dr Max Nordau’s essay ‘Zionism’ was making a fair case that Christian anti-Semitism, which for thousands of years had served as a trigger for assimilation, should be more broadly acknowledged. The Jew did not need to settle for being “absorbed by his Christian surroundings.” Whilst Nordau was prepared to recognize the part played by the Russian Orthodox Church in the various mechanisms of persecution, Gorky saw the root of the problem as lying elsewhere. The message he had for Russia and the rest of the world was that it wasn’t the prejudices of the Russian people that were to blame, it was the failure of Tsarist government. The failures created a storm — a huge gigantic mass of revolving air that super-charged the masses and sent them roaring through towns and villages, uprooting and destroying everything in their wake. But in pushing them forward as social martyrs, Gorky and others like him were using the suffering of the Jews as a damning political battering ram. They were re-directing the energy flow, changing the path of the storm. Giving aid to the Jews would be giving aid to the revolution. The idea of organized militias and self-defence and a politicized response to the ‘Jewish Question’ — which seemed to be what Zionism was offering — must, in the short-term at least, have excited him a great deal. Drawing on the warm humid air of Jewish suffering was becoming an increasingly strong current in revolutionary thinking. And it was in this deeply divided, but highly-charged rhetorical environment that Jabotinsky arrived in Saint Petersburg.

Although Jabotinsky provides no firm explanation of his decision to move from Odessa to Saint Petersburg in the last few months of 1903, his arrival in the city seems to have been brought about, at least in part, as a result of attending some illegal meetings back in Kherson sometime in the autumn of 1903. Russia’s Minister of the Interior, Vyacheslav von Plehve had issued a circular to the Governor of Kherson just weeks before banning any Zionist activity in an attempt to restore some kind of order between its Christian and Jewish communities and douse the flames of National Separatism now licking at its fragile harmony. [14] The atrocities in Kishinev had a sparked a rash of lesser assaults and rampages elsewhere and a series of emergency measures had been hastily introduced to deal with those towns and villages experiencing the worst excesses of the violence.

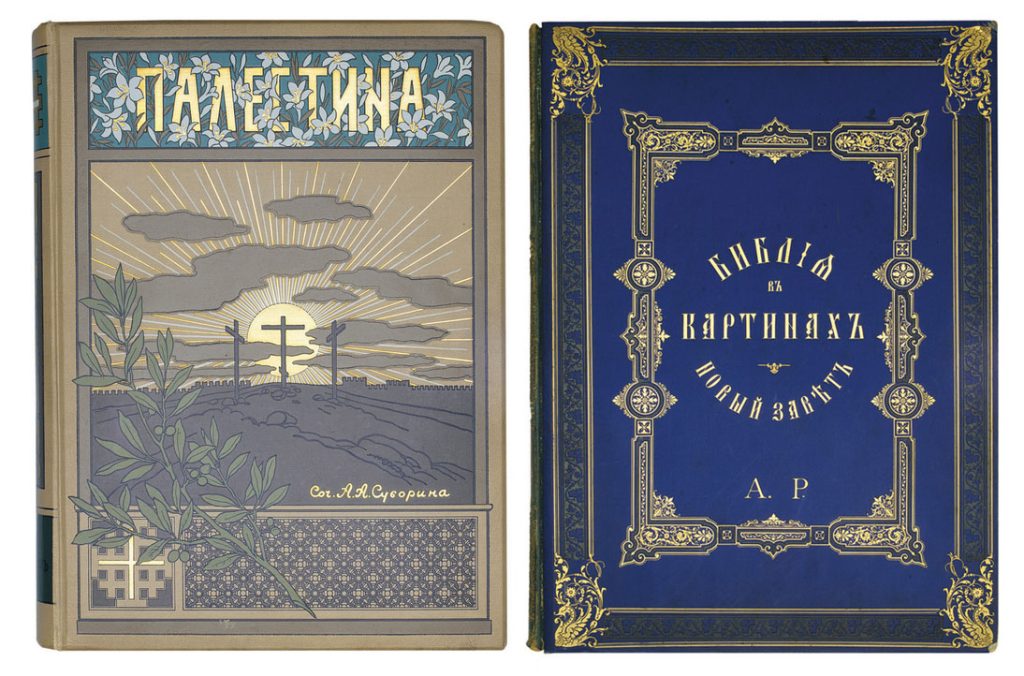

Jabotinsky’s failure to abide by the new emergency regulations saw a warrant issued for his arrest and he fled north to St Petersburg, accepting an invitation by newspaper owner and editor, Nikolai Sorin, to come and contribute articles for Rassnet and his new Russian-language, Zionist Evreiskaia Zhizn (Jewish Life). According to Joseph Schechtman’s biography, Jabotinsky was legally registered as Sorin’s ‘domestic servant’ at his home at 11 Pushkinskaya Street — just 200 yards or so from Gorky’s apartment at 20/16 Znamenskaya Street. [15] The decision for this was simple: only Jews who satisfied certain criteria were permitted to live in the city and the only exceptions to this rule were the Serfs belonging to the privileged classes. In spite of this, it seems almost certain that the Police were turning a blind eye to the activities of the Zionist militant and the reason for this may partly explained by another invitation he had accepted shortly his arrival, this time from Alexei Suvorin Jnr — the more marginally more liberally-minded son of notorious anti-Semite Aleksei Sergeyevich Suvorin, whose newspaper, the Novoye Vremya employed Okhrana agent and Witte’s secretary, Ivan Fedorovich Manasevich-Manuilov, the man responsible for penning the very first account of Gapon’s death and handing it across to John Dover Wilson at the Manchester Guardian. A life-long member of the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society, Suvorin the Younger had been responsible for publishing the richly illustrated publication, ‘Palestine’ in the 1890s and the region and its fertile belt of holy sites maintained a special place in his heart. Whilst it’s entirely possible that Suvorin and his father were secretly backing the creation of a Jewish outpost in Palestine in collusion with a reactively small circle of Odessan Zionists like Dr Shaevich and Dr Shapiro (Sapir), there was no doubting the sincerity of his Russian Orthodoxy. A National Conservative like his father, it may be presumed he had more of a conscience and represented the emergence of a new liberal consciousness among the most celebrated heirs of the autocracy and as a result of this, possessed a greater commitment to resolving the violent tensions that were always threatening to spill over into revolution.

Jabotinsky’s editor-in-chief at Evreiskaia Zhizn was the respected scholar and solicitor, Moisei Markovich Margolin, the founder and sitting secretary of the Efron Encyclopaedia and Dictionary. For some readers the name may be familiar, as it was Sergei Pavlovich Margolin — another St Petersburg solicitor — who provided had legal counsel to Father Gapon before, during and after his meteoric rise to fame as the dashing revolutionary pin-up boy of the 1905 Revolution. It’s entirely possible that Moisei Markovich and Sergei Pavlovich (1853-1906) were related in some way as the Margolins also produced another prominent activist-solicitor, Arnold Davydovich Margolin — the son of Kiev industrialist, David Semyonovich Margolin (1850–1918). Gapon’s lawyer Sergei Pavlovich Margolin was the son of the Hebrew scholar, Pavel Vasilyevich Margolin, who had converted to Christianity under the Russian Orthodox Church. After becoming a member of the Odessa Council of Attorneys at Law, Sergei rapidly became involved in defending cases of a political, sensational or a propagandist bent. At the time of his sudden death in Germany at the end of July in 1906, rumours abounded among Sergei’s friends that he was well on the way to solving the death of Father Gapon and had in his possession a collection of documents that would have implicated high-ranking officials in St Petersburg. [16] At the time of his death , Sergei was also representing Rear Admiral Nikolai Ivanovich Nebogatov of the Imperial Russian Navy after he and his men were accused of surrendering battleships at the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905. His namesake, Arnold D. Margolin would take up a leading role in the Union for the Attainment of Equal Rights whose work would be undertake with astonishing passion and commitment by Jabotinsky in the weeks and months to come. Arnold and Jabotinsky would also be united in the highly commendable Jewish Legion of the First World War and the infinitely more problematic, Petliura Affair, featuring Ukrainian separatist (and alleged pogromist) Symon Petliura.

The greater volume of Jabotinsky’s work in St Peterburg consisted in producing credible counter-narratives to the huge wave of assimilationist and semi-assimilationist sentiments that readers of Nikolai Sorin’s new journal Jewish Life would be up against daily. Sorin had secured permission from the Tsarist ministry to publish the journal and convert it into a serious organ of Zionist propaganda only weeks before Jabotinsky’s arrival. By January 1904, his very first article, ‘Na Voprosy dnia: fel’ton’ had been published. [17] When not writing for Sorin, Jabotinsky was engaged at Russ, the Liberal Russian magazine financed by the employer of Okhrana agent and the writer of the exclusive on Gapon’s death, Ivan Fedorovich Manasevich-Manuilov. It was an extraordinary appointment no matter which way you looked at it. Like Sorin’s Jewish Life, the newspaper had been set-up within months of Jabotinsky’s arrival in St Petersburg. It was alleged that Suvorin Snr, becoming increasingly conscious of a “great split of Russians into two political factions” had launched it with the specific intention of capitalising on and controlling the two ends of the political spectrum; he would retain control of the Novoe Vremya, whilst the Liberal organ, Rus would be safely in the hands of his son, the onetime executive editor of Vremya. [18] It proved a successful and very lucrative hunch. By the summer of 1905 Rus was the most widely circulated newspaper in Russia. Suvorin Snr was pretty frank when explaining his own dislike of the Jews. When asked why his newspaper the Novoe Vremya had served some of the most hostile criticism of the Jews of Russia he was reported to have explained quite frankly that the reason he was opposed to them was that they were “more cultured and cleverer than the native population.” His fear was that if the Jews had equal rights with Russians “they would get ahead so fast that they would soon have the whole empire in their grasp.” The law of the survival of the fittest was to be necessarily reversed, and it was only by virtue of brute force that the fittest could be suppressed — “if not exterminated” — so that the unfit could survive and triumph. Although he stopped short of admitting that the government had encouraged the Kishinev massacre, it was his belief that the prefect of Odessa had stepped aside and let the Jews and the Christians slug it out between themselves. [19]

The Liberal credentials of his Rus newspaper, however, were well and truly clinched when his son Alexei Jnr published the controversial manifesto by Trotsky’s Soviet of Workers’ Delegates in full. Responding to the Tsar’s October Manifesto pledging a consultative Duma, the Workers’ Council had released a statement claiming that the government had declared civil war on the proletariat. Set up just weeks before in preparation for a general strike, the Worker’s Council issued a stiff rebuke to the Tsar’s proposals: “The government continues to defy a people now on the road to liberty, where nothing can stop it. All police measures and the armed intervention of troops can only result in sanguinary conflicts, for which the government will be responsible.” [20] As a final gesture of reproof, Trotsky also called for the repudiation of all debts incurred by the Tsarist government — a demand more successfully repeated during the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917. The whole issue was fundamental to the true release of the Russian people. In order for the complete collapse of the Tsarist autocracy, full financial bankruptcy was essential; the debts the Romanovs had incurred were their own and not the peoples’.

It was clear that the Socialist Democrats and Revolutionaries were seeing their dreams of a mass insurrection collapse. Within 24 hours Trotsky and several of his comrades within the St Petersburg Soviet had been arrested. The belligerent and unyielding hard line taken by the mini-Soviets did little to ease the tensions in Odessa where Jews were preparing for another attacks by Tsarists garrisons convinced that the strikes were the work of Jewish provocateurs. On the day that Trotsky’s manifesto was published, Jewish community leaders released a statement by Special Courier reporting of anti-Semitic speeches being made in the garrisons, the soldiers being especially frustrated by accusations that they had taken part in previous assaults on the Jews. An appeal was for calm was issued. [21]

Jabotinsky’s sponsor, Alexei Suvorin Jnr. defended the publication of the Workers’ manifesto and challenges made by other dissidents on the basis that the paper was reporting communications and proclamations that the represented the opinion and the facts of Russians current political life. The views expressed were those of certain circles of society, and that to have ignored them would have been am abject failure of the press. As far as he was concerned the press operated in a no less neutral fashion than the Red Cross did during a war. An appeal was immediately launched after the unusually heavy-sentence served on Suvorin’s son drew a furious reaction within Liberal circles and among the friends he had made in America. [22] On January 20th 1906, it was announced that Suvorin’s son and Jabotinsky’s editor, Alexei Suvorin Jnr had been sentenced to one year’s imprisonment for crimes against the autocracy. His bail was set at 5,000 roubles and for a time at least, he managed to remain active in his editor’s chair whilst his team of legal advisors set about having his sentence quashed. After fighting on the side of the ‘Whites’ during the Russian civil war, Alexei would commit suicide in 1937, shortly after arriving in Paris to launch a new business venture.

Just days before the murder of Gorky and Rutenberg’s friend, Father Georgy Gapon, the New York Herald was reporting that the priest had been re-arrested as a result of the Tsar rejecting his legal appeal. [23] He had previously been pardoned by the Tsar in July on the personal recommendation of Ivan Shcheglovitov, the man who would launch a bitter prosecution against Kiev Jew Menachem Beilis who had found himself accused of ‘blood libel’ — the anti-Semitic fantasy of ‘murder rites’ that provided the necessary pretext for the Kishinev and Bialystock massacres. The man who became famous the world over for defending Beilis in court was Arnold D. Margolin.

A Pogrom in Moldavanka

Within days of the Tsar’s Constitutional Manifesto being published in October 1905, Jabotinsky’s old defence base in the town of Moldavanka would become the focus of one of the most horrifying episodes in Odessa’s history. The appalling event started when small groups of Jewish workers bearing Red Flags had asked another group of workers to doff their caps to the flags and embrace the reforms being promised by the Tsar. Within hours, a fairly localised series of fractious encounters between Jewish and non-Jewish workers had escalated into a full blown pogrom. Jewish men and women were decapitated and children were torn to pieces. There were even reports of pregnant women having the foetuses ripped from their stomachs and then replaced with straw. The extreme rightist group, The Black Hundreds had poured into town, plying the locals with drink and feeding them rumours of ritual murders of Christian children. The month-long killing spree would horrify the world. By November 6, The New York Times and London Standard were reporting that over 3,500 people lay dead, with over 12,000 now sick and wounded. In Moldavanka, over a thousand dismembered victims still lay upon the streets. Pits were dugs by troops and every effort was being made to conceal the true number of Jewish deaths. The Standard described how two private doctors were now attending to over 300 children who had received horrific sword wounds to their heads. In the Jewish Quarter of Odessa, all the bakeries and shops and nearly all 600 homes had been destroyed. The 140 casualties counted so far had suffered some of the most grotesque barbarity: skulls had been battered with hammers, tongues were torn out, nails had been driven into bodies, eyes were gorged out, ears had been severed and those who had survived were rolled around in spiked barrels. Many of the bodies had been disembowelled and in some cases petrol had been poured over the sick and wounded hiding in the cellars and then torched.

By the end of the attacks over 500 arrests were made. Although some blamed the Jews for their provocation, the general feeling was that the outrages had been engineered by the Holy Synod (the Russian Church) in St Petersburg but the truth is likely to have been a lot more complicated. A three-page eye-witness report in New York’s Hebrew Standard painted a far more complex scene, with some of the worst provocation seeming to come from the student revolutionaries who were firing on police. Once the chaos took hold, it then came the turn of the priests who instructed their flock to turn on the Jews. Not everyone heeded this call. Within hours of the first attacks, a group of Christian working men belonging to various Socialist organisations consolidated with the Jewish Self Defence to form something of a local militia. According to some reports, this ‘Citizen’s militia’ had been able to offer some resistance and save a number of lives but any success had been short-lived. Within hours the Police had arrived and disarmed them, shooting them where they stood with their own revolvers. Wagons full of corpses rattled lifelessly through the streets and the Jewish Hospital was struggling to cope with thousands of frantic, demanding casualties.

It’s not entirely clear where Jabotinsky was at this time. His account of this period in his memoirs is a little short on detail but if his memory serves him correctly he was in Montpellier in Southern France when he learned of the Manifesto and the spontaneous spree of violence that had erupted in Moldavanka some twenty-four hours later. He’d spent some of the summer of 1905 at the 7th Zionist Congress in Basle before heading back to St Petersburg for the meeting in Salt City sometime in November. Jabotinsky doesn’t explain what he was doing in Montpellier at this time — the town being some 500 miles in the opposite direction to St Petersburg — but it’s curious to note that the Foreign Section of the Russian Secret Police had a section in the town where agents were regularly commissioned for special work. Another man who was reported to be in Southern France in October 1905 was Father Gapon. However, as tempting as it does to weave tantalising theories of intrigue and conspiracy under the dazzling canonical towers of this cosmopolitan southern port, it needs to be said that there was also a small but influential group of Zionists operating out of Montepellier during the first years of the 1900s. Many of them like Joshua Bukhmil, Samuel Mohilever (who had been chief Rabbi of the crisis-hit Białystok at one time), Kalwaryjski and Boris Katzmann were already busy on existing Palestine projects with Baron Edmond de Rothschild.

Discussions on the significance and meaning of the Białystok pogrom, both in terms of how it was being perceived in Russia and how it was being treated in the global press saw the fragile coalition between the various Jewish action groups begin to fracture, leading to a dispute between the co-author of Gapon’s pamphlet calling for worker support for the Jews, S. An-sky and Jabotinsky who was now a powerful voice in the Political Zionist movement. Jabotinsky didn’t see things the way that An-sky saw them. He saw the failure to acknowledge the part played by peasants and workers in the violence against the Jews in Białystok and Kishinev as an astonishing calumny and betrayal. Although he accepted that the workers had not have started the pogroms, the Jews had been abandoned by them nevertheless. Writing in his 1936 autobiography, The Story of My Life, Jabotinsky described the short-lived surge of joy flooding through his veins as learned first of the declaration and the pyroclastic anger that it sent hurtling towards the Jews as loyalist Tsarist peasants reacted. Returning to St Petersburg, he attended a meeting called by the Zionists at a hall in the city’s Solianyi Gorodok district. The district, known locally as ‘Salt City’ stood on the banks of the Fontanka River, approximately in the region of where the Museum of Defence stands at 9 Solyanoy Pereulok today, about two or three hundred metres from the Okhrana’s original 16 Fontanka address and a 20 minute walk from Maxim Gorky’s apartment at 20/16 Znamenskaya Street (now Vosstania Street) — an apartment the author shared with Konstantin Pyatnitsky, the founder of the publishing house, Znanie where Gorky now served as editor and director. The meeting was attended by Jews and non-Jews alike and devoted exclusively to the whole issue of Jewish exclusion from the terms and conditions being demanded by the Worker’s movement. The Socialist Democrats and Socialist Revolutionaries had issued their statement rejecting the Tsar’s proposal but at no point had it mentioned the nationwide slaughter of Jews that had erupted its wake. When it was Jabotinsky’s turn to speak he took no time in making his point clear: people had tried to console them with the knowledge that there were no workers among those who embarked on the week-long vicious killing sprees — that the Russian proletariat stood for “equality and fraternity of all races”. For Jabotinsky though, the proletariat did something worse, “they forgot us”. That was the “real pogrom” he assured them. Menachem Ussishkin stood up and levelled a similar criticism: “the followers of Marx and Lassalle will forget about the sufferings of the people which produced these leaders just as easily as the followers of Jesus Christ and the Apostle Paul have forgotten their origin.” A similar tack was taken at the home of lawyer, Mikhail Isaakovich Sheftel a few weeks later to no less overwhelming support. The ‘Goyim’ at the meeting — the non-Jews — bowed their heads as he said it. Out of shame or respect, we don’t know.

By February 1906 Jabotinsky’s conditional support for the Duma, based around a pragmatic appreciation of the short-term gains for the Jews, which would provide a route toward national autonomy, had been terminated and withdrawn. The path was becoming clear: to achieve his goals it would be necessary to separate all Jews from non-Jews and wreck the dominance of the Worker’s Movement. The scale and scope of the violence unleashed on the Jewish populations of Odessa, Moldavanka and Białystok as a result of the publication of the October Manifesto had highlighted the anti-Jewish attitudes within the Russian proletariat, shattering his existing hope that they had no enemies on the left. It was to mark a turning point in Jabotinsky’s efforts to separate the Jewish people from the various regional, religious and cultural mechanisms that prevented their “beautiful unity”. If anything useful was to come from any of it, it would be necessary to reroute all those various energies into a workable solution for Zionism.

A Noisy Rabble

Although it’s difficult to report on the exact nature and scope of Jabotinsky’s literary and propaganda activities during this period, as problematized as it is by disagreements among his biographers and contradictions in his own writings, the writer’s own tendency toward self-mythologizing and the failure of friends, colleagues and acquaintances to follow his movements with any real consistency, he nevertheless appears to have knuckled down to a period of intense productivity at Suvorin’s Rus and Sorin’s Zionist monthly. Much of his time was spent in Sorin’s apartment on Puskinskaya Street. The four-hundred roubles a month he was handed every month from Suvorin whilst and generous and unexpected, didn’t change the fact that he was here an ‘illegal’. As Sorin’s apartment doubled as an editorial office he was able to pour the greater part of his energies into getting Jewish Life off the ground. Competing for elbow space in the one of the chaotic downstairs rooms was Shlomo Gepstein, the man tasked by Gorky with getting Poor Charlotte off the press and in front of readers before the censors had time to act. Gorky himself was just 200 yards around the corner on Znamenskaya Street which likewise doubled as an editorial office. Some twelve years later the street would bear witness to one of the bloodiest incidents of the February Revolution when the Pavlovsky Regiment bore down with rifles and machine-guns on a small group of demonstrators without mercy. The house would also serve as a meeting-place for the city’s radical intelligentsia. Jabotinsky’s own group were called the Halastra, the Polish word for ‘noisy rabble’. Among them was Israel Rosov, head of the Zionist Central Committee in Saint Petersburg.

Much of his journalistic output at Suvorin’s Rus during this time was spent building on the eclectic range of poems, reviews, gossip opinion pieces that Jabotinsky had worked on so prodigiously in Odessa. The man in charge of this section — the ‘Feuilleton’ section — was Vladimir Botsyanovsky, a similarly new recruit fresh from writing a critical biography of Maxim Gorky, for which the writer was to thank him personally. [24] In actual fact, Jabotinsky at this time was writing for a mindboggling range of titles and under various intriguing aliases including A. Z-skii, Vl. Zh, Iunyi Vladimir Zhabotinskii and his most well-known, Altalena. In his memoirs, Jabotinsky says he continued his work without any considerable success and that Alexei Suvorin used to bury most of his articles in his table drawer giving the explanation that “they were not in conformity with the paper’s policy.” If that’s the case then Suvorin was forking-out four-hundred roubles a month to have an illegal Jewish writer, sought by Police in Odessa, work on a paper that was performing successfully enough without him. One explanation is that the conditional and not altogether philanthropic support being offered by the Tsarist government was still being offered on the assumption that the Odessan Zionists presented the best option for leading a mass exodus out of Russia and luring the Jewish radicals into Palestine where they could do untold harm to the Ottoman Turks.

After Zubatov’s dismissal and the break-up of the Independent Jewish Worker’s party, the new Governor of Odessa, General Arsenev put in an immediate request to the Ministry of the Interior to deport Dr Shaevich. Every attempt was being made to restore order, and the Zionist activities that Shaevich had been pursuing in Moldavanka with Jabotinsky and his student friends was clearly an ongoing concern. On July 19th 1903 Plehve ordered Shaevich to be arrested and delivered to the governor in Volgoda for detention. He was to be banished to Siberia and put under Police surveillance for five years. In October 1903 the recently suspended Zubatov personally petitioned the Department of Police on Shaevich’s behalf and he was released on the condition that he did not reside in Odessa or Kiev. This condition was later lifted and Shaevich was allowed to return and join his family back in Odessa. [25] The timing of Gapon’s revelations in The Story of My Life in 1905 couldn’t have been more dangerous. No sooner had Shaevich returned to Odessa than the Revolutionary Priest was telling the whole world about the doctor’s very illegal sideline in Zionist territorial activities. The Bund, who had always considered the group Tsarist provocateurs, had already attempted to ban Shaevich and the Independents some years before. The ‘very real Revolutionary sympathies” that Gapon alludes to in his memoirs to are likely to have made the good doctor fairly precarious position in Odessa all the more the fragile and all the more intolerable for his family. [26] For Shapiro it was a slightly different matter. Russia’s Minister of the Interior, von Plehve had patently been aware of the pleasingly narrow scope of support that Shapiro and the Odessa Society had been giving to their Palestine project and had rewarded that clarity and single-mindedness by re-directing all donations made to the British-backed Jewish National Fund to Shapiro’s Palestine-only charity. And if anybody understood the culture, terrain and political situation with the Turks it was Jabotinsky’s employer in St Petersburg, Alexei Suvorin Jnr whose adventures in the region had seen be so sumptuously and so comprehensively serialized in his books, ‘Palestine’.

The impact of exposing Shapiro was slightly different. In exposing Dr Shapiro as government agent Gapon was effectively saying that the entire Zionist project was just another Tsarist front. A wild and desperate conspiracy theory that had been dreamed up by the Bund to destroy their most immediate rivals was being handed some late gravitas as a result of Gapon’s loose-lipped bestseller. The outcome could have been catastrophic for Jabotinsky and the Odessan Zionists. And from the perspective of his adoring and deeply Russian Orthodox supporters, it wouldn’t have been an entirely favourable development for the Tsar, who’s repressive anti-Semitism had been such a crucial mechanism in maintaining the dominance of the Holy Synod and guaranteeing the grossly unequal privileges of the Russian proletariat. Even if those behind the Palestine-project had been rogue Liberal elements and closet Reformers like former Chief of Police, Lopukhin, Count Witte and Prince Obolensky — determined to resolve the ground-shaking ethnic tensions driving Russia ever closer to Revolution — it would have been the Tsar who would have carried the blame. Of course, it could have been another third-party entirely, like the ultra-Nationalist Black Hundreds, a consortium of wealthy media moguls and industrialists like Suvorin Snr or even the chairmen and members of the Imperial Orthodox Palestinian Society like the Grand Duke Sergei (the Tsar’s uncle and the Society’s President), Alexei Suvorin Jnr, Count Witte (mentioned not for the first time) and co-founder Sergei Arsenyev. When quizzed about the possible Russian occupation of Palestine in 1896 Arsenyev had remarked that many Englishmen would have been happy to exchange the Sultan for the Tsar, the implication being that was probably advantageous to have anyone but the Turks in control of the region. [27]

Palestine – An Imperial Russian Mandate

There had been a general increase in Russian land purchases in Palestine since the late 1880s. The establishment of a British Mandate in Palestine that came in the wake of the Balfour Declaration in the first week of November 1917 — made a matter of days before Lenin and the Bolsheviks seized control of government in Russia — was the conclusion of over twenty years of talks about a possible settlement. In July 1903 the French Ambassador Jean Antoine Ernest Constans was commenting on the new missionary zeal with which Russia was renewing her efforts in the Holy Land as a result of Kaiser Wilhelm’s trip to the Holy Land a few years before. The visit had arrived after a swelling of German colonies in and around Palestine, Jaffa and the Plain of Acre. Just weeks before the Kishinev massacre, newspapers all over the world were bearing the ominous headline “Germans in Palestine’. According to one British pundit, Germany, it was alleged, was ‘quietly taking possession of Palestine’. [28] The Kaiser’s unusually productive meet with Zionist leader, Theodor Herzl in Palestine in 1898 had added a certain amount of urgency to Russia’s plans, and no small amount of political currency to Herzl’s movement. The most natural men for Russia to deal with now would have been Herzl’s rival faction of Zionists consisting of Weizmann, Shapiro and Jabotinsky who were none too quietly seething about Britain’s Uganda Proposal — a British-backed scheme that would see a Jewish homeland set-up in Africa and not Palestine. The scheme, which received fierce support from Joseph Chamberlain, inevitably led to several American members of Hovevei Zion accusing Herzl of being in the pay of the English. The man hurling the most ferocious of the insults was the celebrated Austrian Arabist, Dr Eduard Glaser who had been sharing his view that Zionism was “nothing but an English catspaw for the partition of Turkey and the creation of a petty State” as far back as 1898. [29]

By 1903 the generally accepted view among Turkish and German Ministers was that Russia was in the process of setting up a commercial agency in Palestine as it had in Egypt and Asia Minor for the purpose of exporting Russian goods which has thus far been under very restricted sale. Ambassador Constans would remark that the number of Russian churches and schools in Syria and Palestine had doubled in the previous three years. The Tsar had also purchased one third of the Mount of Olives and had enclosed this and the Gethsemane Church by a high, protective wall. But the hunt for greater success in the region had encountered some serious set-backs. The Russian merchants who had set-up shop in Syria and Palestine had failed to understand the needs of the region’s native populations and there was little or no chance of Russia’s ‘New Jerusalem’ thriving. [30] Suvorin and the Palestine Society had made several attempts to obtain the support of Russian officials in the promotion of its Pan-Slavic ideals in the area, but it was only when Germany started making its Jewish advance that the Tsar and his people had started taking an interest. Five years previously, the British Consul in Jerusalem had cabled the Foreign Office describing his belief that Pan-Slavism in Macedonia helped supplement the Orthodox influence of the Holy Mountain (Mount Zion). Whilst acknowledging that there were few genuine Slavs, the Consul went on to explain how there were plenty of Russian subjects, most of whom were the Ashkenazim Jews, “the erstwhile inhabitants of Poland and the Ukraine, who, driven thence by a relentless persecution, find themselves to their astonishment persona grata to the Russian Consul-General in Jerusalem.” [31]

Whilst some pointed the finger at Kaiser Wilhelm and his concerning trip to the Holy Land in 1898, others saw the renewal of Russian interest in Palestine as a response to increasing tensions between the Russian Orthodox Church and Greek Orthodox Church who, it was believed, were the most aggressive opponents of Russian expansion in the region. Contrary to what many might think there was considerable rivalry and antagonism between the two churches. It was claimed by some that the main objective of Suvorin and Grand Duke Sergei’s Palestine Society was the removal of the Greek Clergy from Palestine and Syria. It was felt that all those Greeks who remained would have no other option but to embrace Islam. This, it was believed, would leave the field free to the Russians. [32] The response of the Turkish Sultan to Russia’s toe-dipping activities was to further restrict the number of Jewish Russian immigrants entering Palestine — not because he objected to the Jews, but because he feared that such a movement might serve as a pretext for Imperial Russia increasing its grip on the Holy Land. [33]

The Ugandan proposal was to meet such fierce resistance within the Greater Actions Committee of the Zionist Organisation that it threatened to split the already fragile movement in two. Looking for alternatives to put forward at the Congress, Herzl sought to open discussions about the Palestine project with Russian Interior Minister, Vyacheslav Von Plehve. At a meeting in St Petersburg on August 8th Plehve explained how the Imperial Government of Russia now pledged to “resolve the Jewish Question in a humane manner.” After much consideration they had decided to balance the needs of the Jews with those of the State. They had decided that the most practical way of assisting the Jews was to give aid to the Zionist movement which would consist of the following: effective intervention with His Majesty, the Sultan and obtain and charter to colonize Palestine with the exception of the Holy Places. The administration would be managed by the Colonisation Company and set-up with sufficient capital by the Zionists. [34] Russia’s pledge was based on practical rather than on altruistic motives. On the one hand it would help extend the political influence of both countries in the Middle East and in Russia, it would also starve the revolutionary Jewish Bund and the Socialist Democratic and Revolutionary movements of some of their most powerful leaders and combat activists. [35]

Jabotinsky, was evidently more supportive of the Tsarist Palestine proposals being made by von Plehve and supported by the Palestine-only ‘maximalists’ among Odessa Zionists. For the Russian state, having someone as resourceful and adaptable as Jabotinsky directing the scope and texture of the Zionist movement from within the Russian capital and having its scholarly agent Dr Shapiro maintain a tight grip of the Palestine coffers back in Odessa would have provided a strange but practical contingency move from the Palestine Society. However, it wouldn’t have been without stiff opposition from the more powerful Socialist Democrats, Jewish Bund and Constitutional Democratic Party who were still pushing the ‘assimilationist’ agenda. As far as these groups were concerned, the Jewish national identity could be just as fully realised and expressed in Russia. There would be no need for a mass exodus to Palestine. When the Sixth Zionist Congress finally took place in August, the Ugandan Scheme suffered a resounding defeat.

For any reader struggling to keep track of all the various cast members, it may be worth recalling that the President of the Palestine Society — the Tsar’s uncle, the Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich — was the very man who had not only expelled 20,000 Jews from Moscow in the very first week of his work of Governor, but also the man who had personally backed the very experimental legal unions that were rolled-out by Zubatov that had Father Gapon and Dr Shaevich as leaders. Just eight days before Gapon led his fateful march on the Winter Palace, the Grand Duke was forced to resign his governorship after thirteen years of service, unable to conceal his fury over the large number of concessions the Tsar was making in his efforts to maintain civil order. It was the belief of the Grand Duke that the strongman tactics that Russia now required were collapsing as a result of weak and inconsistent leadership. We can only speculate if the shock resignation of the Grand Duke Sergei had any bearing on the decision taken by his older brother, the Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich to open fire on Gapon and the demonstrators in the absence of the Tsar. Whether it had any bearing or not, within weeks of the event the Grand Duke Sergei, President of Suvorin’s Palestine Society was murdered by the Warsaw-born Socialist Revolutionary, Ivan Kalyayev. [36]

The Chosen People

One of the more curious episodes to take place during this period was when audiences in London had the rare opportunity of seeing Evgeny Chirikov’s three-act play, ‘The Chosen People’ making its British debut at the Royal Avenue Theatre in Charing Cross, London. [37] The viewing came just 24 hours before Gapon embarked on his disastrous, bloody march on the Winter Palace. The play, originally entitled ‘The Jews’ took a lively and dramatic look at the lives and struggles of an ardent Zionist and a young assimilated liberal living in Russia’s notorious Pale Settlement and was unique for having been produced by Alexei Suvorin’s Literary and Artistic Society Theatre on the Fontanka River Embankment in St Petersburg. Within days, however, the performance had been banned. By an extraordinary coincidence, the man who had persuaded Suvorin to take the play on tour was Gapon’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ saviour, Maxim Gorky, who, by all accounts, had conceived of the idea originally. According to the Boston Post, Gorky is alleged to have told Orleneff to “take this play and carry it to the extreme ends of the world; it is our tribute to the innocent race suffering in our country.” [38] The play’s writer, Evgeny Chirikov’s had become acquainted with Gorky in the author’s hometown of Nizhny Novgorod after being expelled with Lenin from the University of Kazan in 1887. With the cooperation and support of the Central Committee of the RSDLP, the pair had ploughed their efforts and resources into launching The Znanie Publishing Company in St Petersburg, specialising in Socialist and preferably atheist books and pamphlets. Despite his clear reservations about religion, the press would describe Chirikov as an “ardent student of Zionism.” [39] As it was Znanie that published Jabotinsky’s poem Poor Charlotte, it may be surmised that Jabotinsky had some input into the play’s conception and that he may even have advised its writer on some of its Zionist content.

On the day of its debut performance, London’s Pall Mall Gazette gave a tantalising preview, with every effort being made to provide some much needed context. The play’s writers and producers Evgeny Chirikov and Pavel Nikolaevich Orlenev were Russian Orthodox Christians. Whether by error or prank on behalf of the performers the newspaper described the show’s stage manager, Dr Nicholas Orlov as a Russian Jew born in Gapon’s hometown of Poltava. Orlov, however, was none other than the show’s producer Pavel Orlenev using his more commonly known stage name in Russia. The exact reasons for the deception — or error — remain unknown.

Some six months earlier, a student production of the same play had been produced by S. An-sky, the Jewish author and playwright who had co-authored Gapon’s pamphlet pleading with Russian workers to take a more positive stand against the increase in anti-Semitic violence that was now spiralling out of control in Russia. In that production An-sky had taken the role of the old man, Leyzer and a young Christian student called Nikolai Blinov had played the gentile Berezin who is killed defending Jews in the pogrom that ends the play. Sadly, in all too tragic a case of life imitating art, the 24 year old actor who played him was killed in a real-life massacre some eleven months later in his hometown of Zhytomyr. As in the play, he died defending Jews. [40]

Receptions of Orlenev’s play in England were generally positive, although Edward Algernon Baughan of the London Daily News opined that it may have been little more than a pamphlet in disguise. His own view was that it was not until “the clockmaker, his daughter and her lover are massacred by the anti-Jewish crowd” that the intense suffering of its people was more communicated with any significant passion. The last point Baughan made was a shocking reminder of the sheer weight of racism that dominated discussion, and it was reeled-off in the cruellest, most casual but sadly, not the most uncommon of terms. He started by first apologising for his lack of sympathy, before going on to say that even if the play did provide a true picture of the Jews in Russia then it was not very difficult to understand why they were being persecuted. They were, he lamented, an “out-worn race” that either wrapped itself up in “philosophical indifference” or all too often gave way to “frenetic and hysterical outbursts of visionary enthusiasm.” [41] As the vanguard of Liberal Britain it was hard to fathom the severity of the review from such a customarily supportive newspaper as the Daily News. Just three years later Baughan would write a stellar biography of Ukrainian-born composer and activist, and Nationalist politician, Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Claims that Paderewski was anti-Semitic had been rife for years. In America, the threats to his life were such that he had been allocated a Police escort. It was being claimed that he had given in excess of $20,000 in campaign money to Roman Dmowski to help finance the viciously anti-Semitic newspaper, Dwa Groshe, the organ for Poland’s rightist National Democratic Party. [42]

Rumours aside, there was certainly no denying Paderewski’s resistance to the British proposal of National and Minority Rights for the Jews in Poland when serving as the country’s Prime Minister at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Here he faced awkward and pugnacious challenges from David Lloyd George. The Brits had been pushing for Poland to accept, among other things, a plea for Yiddish to be taught as a Second language in Polish schools. Paderewski had responded by saying that he would not sign the Peace Treaty until all the various provisions for minority rights had been downgraded or removed. He was backed up, surprisingly enough, by Arthur Balfour, the man who just two years previously had been the chief advocate for the establishment of a ‘Jewish Home’ in Palestine. One thing was becoming clear: the arguments in favour of a building a Jewish National identity within the cultural and economic framework of their adopted country had never been so firmly rejected. In order to flourish, Zionism — at least within the terms defined by the likes of Balfour — depended on the prejudices and ethnic restrictions imposed on Jews by their host nations. Too much autonomy in other parts of the world undermined the very pretext on which the return to Palestine was being built. The crucible that would help forge a New Jerusalem would need the hot, molten fury of the oppressed Jewish masses to fully take shape. The balm of tolerance and understanding certainly couldn’t be allowed to cool it.

Curiously, Paderewski had found himself occupying a position, and facing similar claims of ethnic violence and disqualification as Jabotinsky’s Ukrainian ally Symon Petliura. However, Paderewski was able to sidesteps accusations put to him by America’s Herbert Hoover that any Jews who may have been massacred in Poland were massacred not because of religion or race but because they were suspected of Bolshevism. [43] Having been nominated by the British to represent Poland at the Paris Conference it was hard not to be cynical and view his — and Symon Petliura’s — rough, uncompromising tactics as somehow expediting Churchill and Balfour’s plans for a Jewish Nation in Palestine. But in all fairness, it is a view that fails to take into account the parallel demands of Polish and Ukrainian separatism that both men were facing. A very small window of opportunity had been presented and it was necessary to adapt. The focus of their own fight was for the independence and national determination of Poland and the Ukraine. Conceding no small amount of autonomy to minorities, however browbeaten and demoralized, would have been counter-productive. Like Russia, every attempt was being made to unite a complex, divided people. Nations within nation did little to help the cause, and Britain knew this. Getting what the Empire wanted was just a matter of balancing statecraft with stagecraft.

Perhaps Baughan’s cheap and deeply insulting comments were intended to provide the necessary stimulus for lively debate or perhaps they were simply the shameful manifestation of Western hubris; it’s sometimes very difficult to know for sure during this tense ‘awakening’ period. After a short season in London, the play proceeded to America — its original destination. [44] Today it ranks as the very first time that a Russian dramatic actor was to perform in the US.

A Wandering Soul

1000 miles away in Saint Petersburg, Vladmir Jabotinsky was stepping up his campaign against the assimilationists and the Jewish Bund. His mind had been made up: Russia was not like France or Germany. There was no place here for the “Katsaps of the Mosaic faith” — a derogatory term he would use to mock the Jewish members of the Constitutional Democrat Party (the Kadets) and their instinctive urge to downgrade the unique interests and needs of the Jews in favour of more generic libertarian principles. From Jabotinsky’s point of view, Russia was a multi-nation state and their specific national needs were not being recognised, let alone being offered solutions. The very idea of a Jewish Nationality was rejected among most Jewish and Christian liberals. Being a Jew was one’s religion, nothing more. Slowly over the course of 1906 Jabotinsky found himself at war with the “National Assimilators.”

Gapon’s new best friend, the Socialist Revolutionary, Shloyme An-sky had found himself at a similar crossroads. Within weeks of the ‘Bloody Sunday’ revolution of January 1905, An-sky and the priest Father Gapon would sit down in London to co-write their appeal on behalf of the Jews to the Russian workers, the writer had become increasingly conscious of a split that had been developing along the ethnic fault-lines of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. Increasingly anxious about the escalation in violent pogroms, An-sky wrote to one of his oldest and dearest friends, Chaim Zhitlovsky. Chaim would be the man who Jabotinsky would enlist to join Gapon’s assassin, Pinchas Rutenberg on his tour of the United States in support of a Jewish Legion in 1915. It was during the course of this trip that the pair had founded the American Jewish Congress — again at Jabotinsky’s bidding. Two years later it would be Zhitlovsky who would also put up the $26,000 bail money for Lithuanian-American anarchist Emma Goldman. At the time that An-sky contacted him about his party concerns, however, Chaim was on a fund-raising tour of the US with the 60-year old ‘Grandmother of the Revolution’ and Socialist Revolutionary leader, Catherine ‘Babushka’ Breshkovsky. As Gabriella Safran explains in her 2008 biography, Wandering Soul, An-sky wished to quiz the veteran Zionist about an idea that was taking shape in his mind. Although he would have dearly wished to preserve his commitment to the broader aims of class-based Revolution, the urgency of the Jewish situation was so intense that he felt increasingly obliged to plough a significant fraction of his time and energy into resolving the issues of Jewish self-defence and furthering the interests of a broad-based Jewish Nationalism. To this end, An-sky had formed a multilateral committee featuring two Zionists, one Bundist and two Socialist Revolutionaries. [45]

Although it’s more generally assumed that Rutenberg converted to Zionism only after the murder of Gapon whilst exiled in Italy, there are some indications that he had been active in the movement during his formative years in Romny and Potlava. The preface he was to write for his 1914 pamphlet, “The National Revival of the Jewish People” — written under the watchful eye of Jabotinsky in Italy — certainly gives that impression. The fact that his passion for Zionism should even take place in Italy is just as intriguing. It was here in the late 1800s and early 1900 that Jabotinsky received his education and formed the first of his Socialist contacts. According to his 1936 autobiography, it was Italy that shaped his own response to Zionism and to all the various notions of nationality, state and society that informed the remainder of his political and ideological life. [46] In Rome he had been a student at the Sapienza University reading Roman law, Procedure, History and Philosophy and Political Economy, but failed to graduate. In addition to Russian, Yiddish and Hebrew, he spoke fluent Italian, eventually becoming Rome correspondent for Odesskiy Listok. At the university he was tutored in History and Philosophy by Marxist scholar and philosopher Antonio Labriola who would subsequently have an enormous influence on Bolshevism and one Leon Trotsky. Jabotinsky’s friend and biographer Joseph Schechtman attributed his Zionist monism to Labriola’s monistic approach. Under the scholar’s direction, Jabotinsky developed a firm conviction that major changes in national history were brought about by the triumph of individuals and free determination — the glorious deeds of men of will and action. It was in this that he had most in common with Maxim Gorky: “I belong to those who believe that there is an irreconcilable and steadily growing contradiction between the interest of the employer and the worker; that the only possible and inevitable solution of this contradiction is the socialization of the means of production; that the natural instrument of this upheaval is the industrial proletariat; and that the way to this upheaval is class struggle.” [47] In Rome the stories of revolutionary nationalist Garibaldi “enriched and deepened” his “superficial Zionism.” [48]

It was to Italy that Rutenberg fled after Gapon’s assassination, and it was in Italy that he went to stay with Maxim Gorky, whose apartment in Znamenskaya Square had provided sanctuary to Gapon and Rutenberg in the immediate aftermath of the march and where they had plotted their escape to Europe. By 1914 all three of the men — Jabotinsky, Rutenberg and Gorky — were hunkered down safely in Italy. Contrary to the claims that Rutenberg had committed his life to Zionism only after the murder of Gapon, was it possible that he had been among the Socialist Revolutionaries split between their commitment to class-based revolution and the more urgent needs of Jewish Nationalism? Had it been contacts that Jabotinsky had established some several years before in Rome that now provided the firm bedrock of support the author and Gapon’s assassin were able to draw on in Italy for the next few years?

In another curious twist, it transpires that the Balfour Declaration of November 1917 that paved the way for the State of Israel was given its full legal mandate by the League of Nations at Sanremo in Southern Italy — just six miles east of the house that Gapon visited during his stay in Bordighera in December and January 1906. The venue chosen for the conference was the Villa Devachan, built by Bordighera-born engineer and Casino-owner, Pietro Agosti and at that time owned by Turin commander and businessman Edoardo Mercegaglia. The name Devachan had been given to it by its previous owner, John Savile, the 5th Earl of Mexborough. A practising Buddhist, the phrase had been derived from the Tibetan ‘bde-wa-ca’, state of consciousness in Theosophy in which the Ego finds is said to find itself in a condition of illusory bliss after death before reincarnating. As a host for the rebirth of a Jewish nation, the villa couldn’t have been more suitable. The man who built it was Pietro Agosti who had also been responsible for building Sanremo’s Russian Orthodox Church, Christ the Savior, designed by Russian architect Alexey Shchusev, famous for also having designed Lenin’s Mausoleum in Moscow. The likelihood of a trade link between Agosti and the civil-engineer Rutenberg seems plausible, given the eight years that he spent in Italy working on large-scale engineering projects.

Maxim Gorky and Jabotinsky would collaborate for many years to come. When Gorky eventually found favour with Lenin and the Soviet Government after the Second Revolution in October 1917, it was the author that Jabotinsky turned to secure the release of his mentor and literary icon, Hayim Bialik, whose publishing house in Odessa had been seized by the Cheka and its Zionist operations shut down. Gorky also intervened when Rutenberg, now serving as Deputy Governor of St Petersburg under Prime Minister Kerensky, had been imprisoned by the incoming Bolsheviks in November 1918. Rifling through the archives at Gorky Institute in the late 1980s, Soviet historian, Mikhail Agursky stumbled upon a dozen letters from Gorky to Jabotinsky during the period 1903 to 1927. In one historically significant letter dated August 21, 1915 Jabotinsky tells Gorky of his plans to a launch a Jewish Legion in Britain. There was little doubting the respect and admiration that both men had for each other, Gorky once famously lamenting that Zionism and the Jewish people had robbed Russia of a literary giant. [49] The relationship between Gorky and Rutenberg was just as enduring. At the same time that the reformed revolutionary, Vladimir Burtsev had rekindled his own correspondence with Rutenberg, now head of the National Council (Vaad Leumi), in Eretz Israel, Gorky got in touch with him, eager to learn his response to ‘Na Krovi (The Place of Murder), an entirely fresh account of Gapon’s death from the perspective of former Socialist revolutionary, dramatist and editor Sergej Dmitrievic Mstislavskij. As leader of the Combat Worker’s Union and a fellow at Gorky’s Literature institute at the time of the murderous incident, many believed Mstislavskij had been slyly putting himself forward as a member of the team of assassins working under the direction of Rutenberg at the summer house in Oserki. Rutenberg’s reply to Gorky was less than enthusiastic; as far as he was concerned there was nothing else to tell. Mstislavskij’s novelised version of the story was deemed “Not worthy. And not interesting.” Interestingly the pair would also exchange letters on the subject of Italian-Russian cultural ties, making rumours of work for the Italian government from his island hideout on Capri an intriguing possibility (as a member of the Central Powers with Germany and Austria-Hungary, it’s not as implausible as it sounds, given their shared hostility to Tsarist Russia and Jabotinsky and Rutenberg dramatic shift of loyalties to the English at the time that those of Italy shifted to Britain too). When he learned of the death of Gorky in 1936, Rutenberg sent a telegram to his relatives: “With the greatest respect and sadness, I keep my memory of my great teacher and dear friend. Please accept my condolences.” [50]

In a report dated August 30th, the Philadelphia Inquirer recalled the part played by Rutenberg in the 1905 revolution under the alias, Martin Ivanovitch. By July 1917 Rutenberg was back in Russia and taking a leading role in Kerensky’s government as Deputy Governor and Commander of the St Petersburg Home Guard. [51] It’s difficult to say for sure what his intention was at this stage. Just a year or so previously the former revolutionary had published a pamphlet in Yiddish under the pen name Pinchas Ben Ami in which he reiterated his conviction that even if a revolution in Russia was successful and the workers triumphed, anti-Semiticism would remain and the Jewish people would have no other option but to return to the Land of Israel “in which the epic and romantic nature of the Jewish people are bound.” To all intents and purposes, it was Palestine or nothing. Either way, whatever his feelings about the revolution of February 1917, it certainly didn’t scream commitment to Kerensky’s liberation plans for the Jews of Russia.

At the height of the war in 1915, Jabotinsky dispatched Rutenberg on a mission to America to initialise the formation of a Jewish Legion and a Jewish Congress. Seven years later in 1922, Rutenberg had settled in British Mandate Palestine. Here, with the support and backing of Winston Churchill, Herbert Samuel and Lord Reading he would commence work on a hydro-electric power grid designed to substantially improve Jewish prospects in the region. Gapon’s traitorous assassin would become a hero overnight.

Main Image: Vintage Antique pocket watch on the background of old books

Andrei Armiagov (Shutterstock, CS-0D9A8-5F56)

[1] Rebel and Statesman: The Vladimir Jabotinsky Story, Joseph B. Schectman, Thomas Yoseloff Inc, 1956, p. 75

[2] ‘The City of Slaughter’, H.N. Bialik, Complete Poetic Works of Hayyim Nahman Bialik, Israel Efros, ed. (New York, 1948): 129-43 (Vol. I)

[3] Zionism and the Fin de Siecle, Michael Stanislawski, University of California Press, 2001, p.160

[4] ‘The Jihad’, Staunton Spectator and Vindicator 17 December 1909, p.7

[5] Rebel and Statesman: The Vladimir Jabotinsky Story, Joseph B. Schectman, Thomas Yoseloff Inc, 1956, p. 67

[6] Maxim Gorky’s ‘Pogrom’, Amelia Glaser, Shofar, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Summer 2019), Purdue University Press, pp. 166-190

[7] Russia and the Jews, The Shield, Maxim Gorky, Leonid Andreyev and Fyodor Sologub, Alfred A. Knopf, 1917

[8] Maxim Gorky, Maccabean, April 1902, ii, 21

[9] Selbstemanzipation (Auto-emancipation). The notion was based on a pamphlet written by David Pinsker in 1882. Pinsker believed that Jews would never be treated with respect until they had a state of their own.

[10] Gentile Reception of Herzlian Zionism, a reconsideration *, Jewish History 16: 187-211, 2002, Alan Leveson, Cleveland College

[11] ‘Maxim Gorki und Tolstoi ueber Kischenew’, Die Welt, 29 May 1903

[12] Philadelphia Jewish Exponent, December 12, 1902, p.6/ The Jewish Voice, January 16, 1903, p.8

[13] Gentile Reception of Herzlian Zionism, a reconsideration *, Jewish History 16: 187-211, 2002, Alan Leveson, Cleveland College

[14] ‘Russian Move Against Zionism’, New York Times, August 7, 1903, p.3

[15] Rebel and Statesman: The Vladimir Jabotinsky Story, Joseph B. Schectman, Thomas Yoseloff Inc, 1956, p.92

[16] ‘Who is Gapon’s Killer?’, Peterburgskaya Gazeta, No. 202, July 27, 1906

[17] Vladimir Jabotinsky’s Story of My Life, Jabotinsky, Vladimir, Wayne State University Press, 2015, p.83

[18] Boston Daily Globe, March 19, 1905, p.5

[19] The American Israelite, July 4, 1907, p.8

[20] New York Times, December 4, 1905, p.2

[21] ibid

[22] Washington Post, January 21, 1906, p.18

[23] The New York Herald, March 24, 1906, p.9

[24] M. Gorky to Vladimir Botsyanovsky, 18 November 1900, Nizhny Novgorod