Blending into the background and creating a mask is all part of the tradecraft of being a spy, and whether it’s the endless whirring rumours at Gatsby’s parties, the private investigations into his business affairs carried out by his love rival Tom Buchannan, or the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg staring out with haunting intensity from a giant billboard in the novel’s hellhole, the Valley of Ashes, a dark and paranoid atmosphere of surveillance prevails over much of The Great Gatsby. The scene’s impact was so memorable and so intense that it would go on to inspire the dust jacket that Scott’s publishers Scribner’s prepared for the first edition of the novel in 1925. What had caught Scribners’ imaginations was the author’s image of Dr T. J. Eckleburg — the ‘old wag of an oculist’ whose eternal, persistent gaze penetrates the whole, unworthy heart of America. But what was the meaning and the symbolism behind it? Where did the author get his inspiration?

The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic – their retinas are one yard high. They look out of no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a non-existent nose. Evidently some wild wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sank down himself into eternal blindness, or forgot them and moved away. But his eyes, dimmed a little by many paintless days, under sun and rain, brood on over the solemn dumping ground.

The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chapter II

The eyes make their first appearance in the second chapter of the novel when Daisy’s husband, Tom Buchanan takes Nick to meet his mistress. It’s an awkward moment and Nick finds himself shrinking away from his friend to observe the view.

The real life location for the Valley of Ashes was Flushing Meadows, Corona Park, half way between Great Neck and New York, a bleak, desolate wasteland where the poor, wretched underclass of the Borough of Queens would bore out a Morlock-like existence of thankless toil for a meagre few dollars. These were the extremities of New York City and the extremities of the city was where its wealthy city officials had the cool, hard wisdom to cache all the dross of its greedy machinations. It was on the outskirts of a city that they slurried-away all the things that its Old Money patrons preferred to bury at the back of their minds. Everybody knew about the kind of things that went into making the city machine run smoothly and successfully, but you didn’t always want to look at them. It was here that you found the city’s fairgrounds and amusement parks, its asylums and its prisons. It was also where the entire city of New York would dump and then ritually burn its colossal turnover of refuse. The villages and slums around Flushing Meadows were quite literally a Valley of Ashes. A syndicate of corrupt officials had intended using the ashes produced by the fires to soak up the wetlands around Corona Park to create a thriving, commercial port. The garbage itself rolled in on a daily basis as freight on the Long Island Railroad or on trucks being run by the Brooklyn Ash Company. Cars passing through to New York from Great Neck and Sands Point would have to stop their car at a turnpike before being allowed to cross the bridge that spanned its rank, slow-moving river.

As Scott lived on the east side of the river he would have been obliged to make the crossing several times a week driving to and from Manhattan. Scott knew a thing or two about advertising. After being demobbed from the army in 1919 the author had worked as a copywriter at an agency run by Barron Collier in Manhattan. Scott had no misconceptions about the industry. Shortly before his death in 1940 the author would write that like the movies and the brokerage business, the whole thing was a “racket”. It was “simply a means of making dubious promises to a credulous public.” But if he had learned anything during his short spell in the business it was the power that its images had over people. He understood exactly what kind of impact that a giant billboard advertisement would have at this location. It was the perfect trap for the city’s consumers. The cars that clumped here, bumper-to-bumper, crawled along at a sluggish pace, and every so often these weary commuters through hell would be forced to stop as the bridge went up and the ferries passed. The driver, probably daydreaming of better things, would have very little option but to look up from behind the wheel and observe his bleak surroundings. The billboard would be something to occupy their thoughts, stimulate their imaginations or perhaps even shield them of the reality of the wasteland around them. Scott was on the lookout for something powerful, something iconic.

The 28 year-old author had been struggling for the best part of two years to come up with something that could even come close to satisfying the immense expectations the world had for his third novel. But now he had “enormous power building within him”. In April 1924 Scott wrote to his editor, Max Perkins telling him that he could look forward to the “sustained imagination of a sincere yet radiant world.” Something powerful was taking shape. Rising high above the rubble and the colossal soot mountains around him, the author conceived of a ghostly billboard advertisement put there by some unscrupulous Long Island optician with a fairly dark sense of humour. The irony wouldn’t have escaped any readers who knew the area. When the fires burned at their most intense the smoke would have made it difficult to see beyond twenty yards, the mountains of ash, some 80 feet high, only obscuring things still further. Had it really existed, the image of Dr Eckleburg would have been a sight for sore eyes indeed.

The area that Nick and Tom arrive at in the novel is described as a “ghastly creek” covered by an “impenetrable cloud” of smoke. [1] These were the city’s wetlands. The things that weren’t being eaten by the rats were consumed by the shape-shifting swarms of mosquitoes that rippled around the creeks. The area, conceived by the author as the invisible, dividing line between the tradition and wealth of Long Island and the decadence of New York, was “one fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills.” Dickens had his Dust Heaps, T.S. Eliot had his Wasteland and Fitzgerald had his Valley of Ashes.

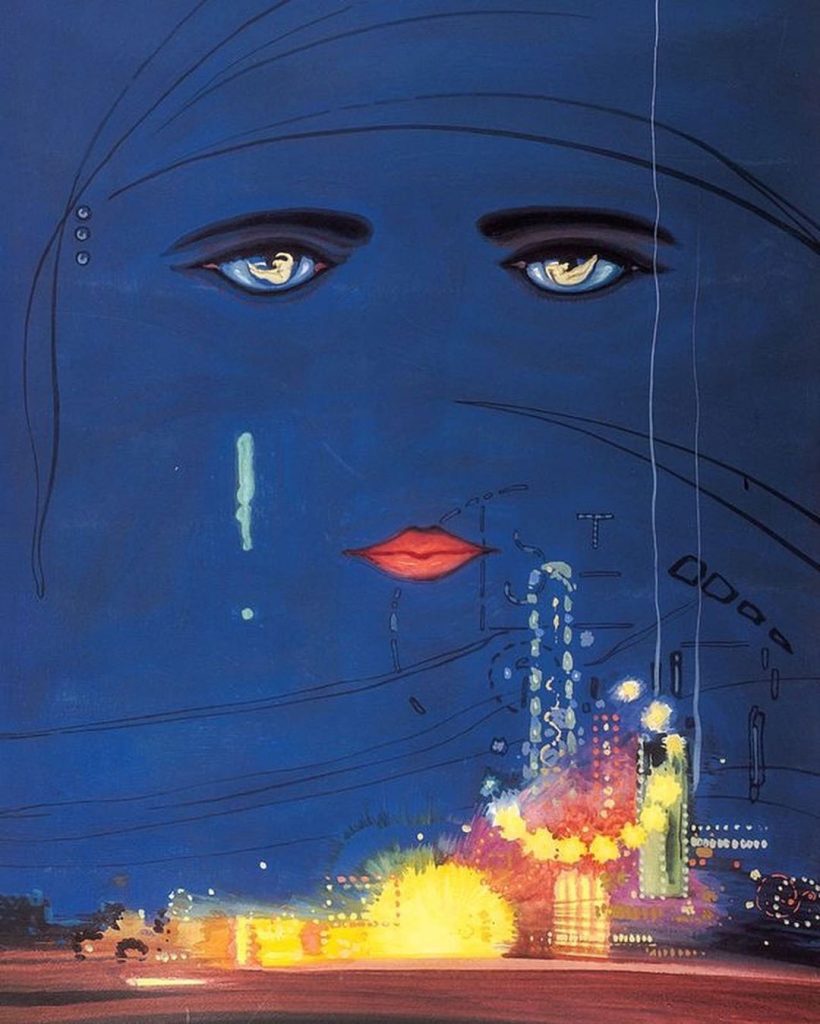

Scott had originally intended calling the novel, Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires but his publisher, Charles Scribner had not been especially keen on the idea. Nevertheless they put their reservations aside and commissioned an artist to produce some ideas for the novel’s dust-jacket — only with one or two adjustments. The detritus of wealth imagery described in the novel by Scott may have worked brilliantly at a poetic and moral level, but the publisher had been quick to realise that it would have been a total commercial disaster if they had featured it on the cover. A story about the depravity of excessive wealth may have been relevant to the times but at a visual level at least, it wasn’t the key to selling the novel. A shot of the ash heaps and the smoke would have been miserable and unappealing. In preference they turned to the magical, more ethereal qualities of the book, taking Scott’s original image and giving it a fresh and sexier twist. Instead of Dr T.J. Eckleburg looking out over the Valley of Ashes, they had Daisy Fay’s enormous two blue celestial eyes staring out above a dazzling Coney Island skyline. [2] This way everybody would be happy. The curiosity of the reader would be aroused, the booksellers could display it on their shelves and promotional stands with confidence and Scott would have something in his hands that justified all his hard-earned Modernist credentials. Even someone with little or no familiarity with artistic movements of the period couldn’t fail to be struck by the novel’s design. It was progressive and cutting-edge, the kind of thing that audiences at the time might be swooning over in the galleries and exhibitions showing the work of the avant-garde artists on the continent. It was a deeply hypnotic image, part-gorgeous, part-grotesque, full of questions and few firm answers.

In years to come it would be clear to everybody that the author of the book and the artist who painted the picture had both been influenced in their creations by the surrealist ‘dream world’ approach of symbolists and surrealists like Odilon Redon, Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso, Man Ray and Max Ernst. Scott and his wife Zelda had been introduced to the Surrealist movement by Gerald and Sara Murphy, two artist friends of Scott who the couple had visited in Paris. The pair would prove to have a substantial impact on Gatsby. Writing to the author, Marya Mannes just months after the book came out, Fitzgerald thanked her for the kind words she had to say about the novel and the excitement she had shown for New York. But in Scott’s estimation America was “the story of the moon that never rose”. It gave promise that “something was always about to happen” but never did. Scott reminded Marya of a visit they’d paid to their mutual friends in France, Gerald and Sara Murphy: “Nor does the ‘minute itself’ ever come to life either, the minute not of unrest and hope but of a glowing peace—such as when the moon rose that night on Gerald and Sara’s garden.” The moment of hope and change was always at hand, but it never came to pass. It was like the old “defunct clock” on Nick Carraway’s mantel that had stopped ticking.

Among the paintings of the period, there is probably few that convey the same haunting quality of Daisy’s ‘celestial eyes’ as Odilon Redon’s charcoal-drawn ‘Eyes in the Forest’ which featured among a selection of paintings and drawings showcased at exhibitions in New York in the 1919-1924 period. The image, dating back to 1885, shows a pair of glowing, disembodied eyes above a dark, enchanted forest — perhaps that moment of “glowing peace” that Scott had glimpsed in Murphy’s garden. In terms of how far we’ve come with the avant-garde it may seem a bit of a cliché to us now, but in Scott and Zelda’s day the image would have been nothing less than profound: “above the grey land and spasms of bleak dust … the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg … they stare out of no face, but instead from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles over a non-existent nose.” The eyes are penetrating the darkness of the valley, probing deep into its soul.

Dr R.A Esslinger

So where did Scott Fitzgerald get his initial idea for the eyes of Dr T.J. Eckleburg? If he had borrowed the idea from actual billboards of this period then its not immediately obvious from a review of advertisements that were appearing in New York and Long Island newspapers in the mid-1920s.* There are plenty of other illustrations in the ads: a pair of spectacles, spectacle frames, your classic ‘Eye of Providence’ motifs, tiny men and women holding preposterously large spectacles, the occasional pince nez, the odd monocle. In one less than tactful advertisement there is a picture of a child wearing glasses. Above it a caption reads: “Most backward children have poor eyesight. How about your child?” Few if any of the ads matched the image described in the novel. The best matches for the image that we see in the novel tend to be among trade-signs of the period, the ones that literally appeared above the premises and which consisted, more often than not, of a pair of unusually large spectacles dangling from a wall bracket above the shop with huge painted eyes staring out of them. [3] One man who had a sign just like this was the respected Long Island Optometrist, Dr Reinhold August Esslinger, previously in charge of one of the oldest and best known jewellery establishments in Saarbrucken, Germany before emigrating in 1902. Once he and his family had made themselves comfortable in New York, the 25 year-old Doctor set up his first practice in Flushing, Queens County, the location of the Valley of Ashes. [4]

In 1907 the Switzerland-born Esslinger would move his clinic to Hicksville, just outside of Huntington Station in Oyster Bay. This would place him around fifteen miles east of Scott and Zelda’s 6 Gateway Drive address in Great Neck. A description of the over-sized spectacles might read uncannily like the image of T.J. Eckleburg in the novel: “the eyes are blue and gigantic … they look out of no face from pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a non-existent nose.” The eyes in R.A. Esslinger’s metre-long, zinc and cast iron trade-sign were blue, the spectacles were yellow and they looked out over a non-existent nose. [5] As antique dealer Dirk Soulis explained to me, “Optometrist signs of this basic design, some with variations, but essentially iron frames of this size with sheet iron inserts, sometimes with a banner below, were very common. Some were completely different, but most were originally gilded like this, rather than being yellow. They were essential to attracting or informing potential customers as cities grew due to the low literacy rate and the number of immigrants who couldn’t read English. A figural trade sign like an outsized pocket watch, or giant boot, a large, hollow top hat or even a tooth with roots were used to inform about goods and services.” Trade-sign or no trade-sign, its effect must have been positively surreal and few would be able to deny the freakishly absurdist impact that the image may have had on a creative mind like Scott’s. The surrealism of the image had been tapped at source. It was already working at a figurative level. As practical as it was, your common-or-garden optometrist trade-sign was like something you brought back from an acid trip.

Esslinger’s profile in a Long Island Who’s Who of the period describes him as a maker of watches from a nation that was famous for its watches. The Doctor had trained in Switzerland, Germany and New York, first as watchmaker and then later as an optician. His practice in Hicksville was said to be known all over Long Island and as a repairer of clocks and watches Dr Esslinger enjoyed the patronage and support of many wealthy Gold Coast families. He was also a prominent and respected charter member of the Hempstead Masonic Club. As a novel that is so preoccupied with the passing of time it seems all the more fitting that the good Doctor who may have inspired the famous image was a skilled and diligent fixer of clocks.

If Dr R.A. Esslinger’s zinc and cast-iron trade-sign or one very much like it had been the original inspiration for Scott’s Dr T.J. Eckleburg, then what the author had done with it had been nothing short of alchemy: Scott had taken the most ordinary of business hardware and packed it with instinctive, powerful symbolism. Cugat’s illustration then took it to a whole new surrealist level. Even if his eyes had needed testing, one thing that certainly wasn’t in question was Scott’s poetic vision. It was the perfect collaboration: Fitzgerald was seeing things like an artist and Cugat was thinking like a poet. Scott had taken something very mundane and commonplace and given it a haunting, otherworldly magic. But this is what you get with writers, they take things that exist in one world and transport them to another, extending their meaning and giving them new dimensions. The issue of immigration and movement is never far away in the novel. Nobody is entirely sure where Gatsby is from. Some think he is German, others an East European Jew. He lives in a fluid world of ideas and impressions, and all ideas are like migrants in some respects. They tend to move around a little bit. Scott had found himself acting as passport officer at the border between the visible and invisible worlds, processing all the things that shuttled between this world and the next, between the literal and metaphorical, the commonplace and the profound, the world of East Egg, the world of West Egg and that twilight world in between.

A trawl through the newspaper archives of the period raises another question: by 1924 the more common name for an optician was not Oculist but Optometrist. If you were to key-in the word optometrist into a search of the digital archives of newspapers in America between 1909 and 1924, more than 30,000 ‘hits’ will be returned in the New York State alone. Search for optician and you’ll get 16,000 matches. Key-in oculist and you’ll get just 23. The popularity of the word Oculist had hit its peak in the mid-1800s (1800 matches between 1842 and 1856). By 1924 the word was practically antiquarian. Had Scott been anxious to preserve the more arcane and mystical aspects of the science? Early 20th century mystics like Gurdjieff had always considered ophthalmology a way of bridging the relationship between the inner world of consciousness and the outer world of phenomena. In the 18th Century there had even been a Highly Enlightened Society of Oculists founded in Germany by Friedrich August von Veltheim which was rumoured to have featured secret initiation rites. The eyes were the window to the soul — even the Egyptian and Sumerian artists recognised that. The word Oculist carried a certain weight. Scott’s excellent grasp of semiotics and etymology suggests it was possible, at least. As a former copywriter he understood the power of words as signs. Words were things that could develop many layers. They acted as hooks and served as triggers. Words had futures, they had pasts.

Art imitating art

As Scott completed his final drafts in Rome, Scribner carried on communicating with the Spanish-Cuban artist, Francis Cugat in New York. Excited by some early ideas for the dust cover shown to him by his editor Max Perkins, Scott added a few lines to his unfinished novel. The words had been specially prepared to support Cugat’s otherworldy image of Daisy: “Unlike Gatsby and Tom Buchanan, I had no girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs.” [6] He’d done what many critics might regard as a first in literature: he had taken the idea for the novel’s artwork and written it in to the book. The line comes just as Nick and Jordan are heading out of New York along 59th Street as the they make their way along the south side of Central Park, past Carnegie Hall and The Plaza Hotel and onto Queensboro Bridge. Completing the final drafts of his novel in France in August 1924, Scott wrote urgently to his publisher, “For Christ sake don’t give anyone that jacket you’re saving for me. I’ve written it into the book!”

Not everybody was impressed by the cover. Ernest Hemingway, a friend of the author, thought it “garish”, full of “violence” and “bad taste”. Writing in A Moveable Feast of the time that Scott brought over a copy of the novel, Hemingway teased him that it “looked like the book jacket for a book of bad science fiction.”

Look a little more closely at Cugat’s illustration and it is just about possible to make out the figure of a male and female nude reclining in the irises of Daisy’s eyes and some kind of solar flare exploding on the fairground scene below. “He dispensed starlight to casual moths,” says Nick as he mulls over the idea that Gatsby had bought his mock-Gothic mansion for the sole purpose of wooing Daisy. Fitzgerald makes quite a big deal about light in Gatsby. Gatsby is the Long Island Sun King. His parties are bathed in electric light. On one occasion his friend remarks that his mansion is lit up like the World’s Fair. Barely a page goes by without a skyful of stars twinkling or a full moon shining. A green light blinks at the end of Daisy’s dock, mesmerising Gatsby. Perhaps the starburst effects that Cugat had crafted for the book’s cover were the diffraction spikes of a star as it pulsed away in the night sky enticing moths. The Priest says something similar in Scott’s short-story Absolution, the intended preface to the Gatsby novel, as he sets out to beguile a boy with images of the fairground: “I heard of one light they had in Paris or somewhere that was as big as a star … Did you ever see an amusement park … its a thing like a fair, only much more glittering. Go to one at night and stand a little way off from it in a dark place— under the trees. You’ll see a big wheel made of lights turning in the air … it will just hang there in the night sky like a coloured balloon, like a big yellow lantern on a pole.”

(Princeton University Library for the Graphic Arts collection)

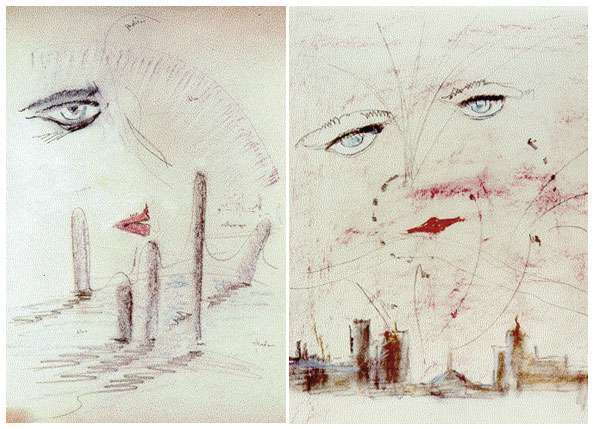

Hemingway was quite right; the picture that we have on the final cover conveys not only a sense of beauty, it also conveys danger. In one of the preliminary sketches produced by Cugat, the scene included the Long Island Railroad that had featured so prominently in Joseph G. Robin’s fall from grace and the transportation of the Corona Park refuse. [7] There is a sense of misery or melancholy running through each of the ideas, not least the final painting. A tear stutters from the eye of the girl. The lips are warning-light red. The diffuse and fractured nature of the light of the fairground scene below it adds an uneasy sense of movement and uncertainty — as if something is about to happen. Scott had taken a trade-sign he had probably seen a hundred times before, reimagined it as a giant billboard advertisement and then woven it into the novel as an ominous if slightly ambiguous metaphor. Cugat had then amplified its spectral qualities and made it a thing of menacing beauty.

The Twilight Zone

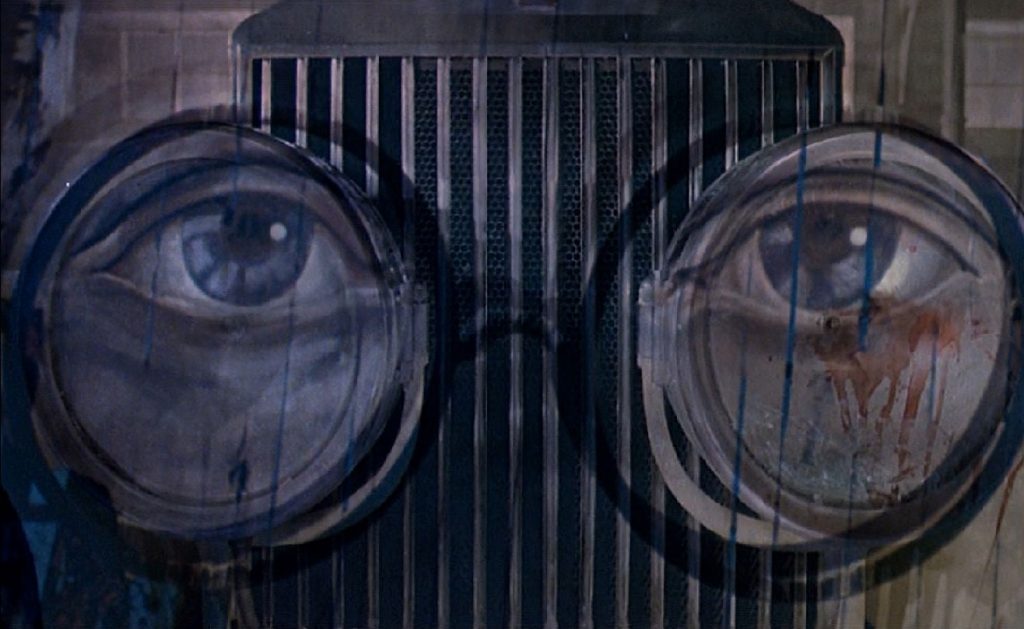

If Jack Clayton’s beautifully macabre 1974 movie adaptation of the novel is memorable for anything, it’s for the way it handles the eyes of Dr Eckleburg. Anybody who has ever watched an episode of the Twilight Zone, Outer Limits or even the X-Files will know exactly what I mean. The way Clayton had trained his camera on the eyes of Dr Eckleburg and panned out slowly to reveal the Valley of Ashes has all the signature notes of your classic supernatural chiller. But it’s not something that Clayton had added, it is already there in the novel. Across the road from the persistent stare of the billboard are three buildings: a garage, a boarded-up shop and an all-night American diner — the Holy Trinity among tropes of the horror and sci-fi genre.

The story itself plays-out like a modern ghost story. It’s the story of a man haunted by his past. What comes back to kill Jay Gatsby at the end of the novel is his former life as plain old James Gatz and there are clues to be found everywhere. The young Jimmy Gatz is “haunted at night by the most grotesque and fantastic conceits”. The future crash-victim Myrtle walks through her husband to embrace Tom “as if he were a ghost”. The crawling line of “grey ash grey” in the Valley of Ashes recalls the shuffling, catatonic march of the “crumbling” undead, men who are missing half their souls. Nick walks up Fifth Avenue and feels “a haunting loneliness”. After Gatsby death “the East is haunted” for Nick. At one point Nick even thinks he can hear the music and the laughter of past parties “faint and incessant” from the garden. He thinks he sees a phantom car. And then of course there is the picture the author paints of the “girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs” as Nick drives along 59th Street.

When Scott’s former mentor Shane Leslie shared his feelings about the book with the author in July 1925, he explained how it had brought back “dead months and dead people” to him. The old world of Long Island that he had known some ten years earlier had come back to haunt him like an “Arabian Night mixed with a Subway Sound”. There were ghosts to be heard in the “bleating” foghorns on the ocean and from the ephemeral flow of guests at its riotous house parties, the ‘floating’ men and women of Great Neck and Port Washington who arrived not as heroes but as “locusts and fireflies”. In essence it’s the story of a large empty house whose ghosts reassemble at night to eerily replay the best and worst parts of their lives, the story of past vibrations leaking into the present. We are left with a strong impression that there are strange and invisible forces at work. When stripped down to its bare bones, The Great Gatsby is the story of two men who haunt themselves. Nick because he walks through life like the living dead and Gatsby because of the boy that he left behind.

I think many people would agree that Scott does little to conceal the novel’s Gothic influences. When the garage-owner Wilson sets out to exact his revenge on the handsome bootlegger he is looking up at Dr Eckleburg’s eyes. They seem to be impelling him to commit murder. “You can fool me but you can’t fool God. God sees everything,” he had told his wife as he forces her to look upon the billboard sign outside their window. The eyes have come back to judge the living and the dead. “Nothing in all creation is hidden from God. Everything is naked and exposed before his eyes”, its reads in Hebrews 4:13. Not one of us is sinless. It’s a book in which the past, present and future collide in one gorgeous and violent spectacle of absolution; like Charles Dicken’s Christmas Carol only with Nick stepping in for all three ghosts. The tragedy, as it is in Dicken’s story, is not that anyone dies in the end, it’s that the novel’s title character — and perhaps even all of the characters — had never truly lived. They are like those gorgeous copper jelly moulds that we see in Gatsby’s kitchen. There is nothing behind the eyes. They are shells of people. The trailer for the original Famous Players-Lasky movie of 1926 had eyes splashed all over the captions between scenes: “Come and see it ALL!” they implore over the disembodied eyes of a woman. It too understood the significance of the eyes in the novel.

Publicist Bruce Bahrenburg’s fascinating account of the filming of Clayton’s Great Gatsby suggests the director was keen to convey the idea that the Valley of Ashes had a certain kind of primitive or visceral power. To Clayton’s mind at least, the Valley marked a place of dangerous passage like a dark, mysterious cave that one might stumble across as a child. What the director was doing, like Cugat before him, was amplifying certain qualities that were already present in Scott’s book. Just take another look at the movie’s eerie intro. For the first five minutes of Clayton’s film the camera roams through an empty palatial mansion at twilight. There is the thin and rather spectral sound of a distant piano playing and people talking but as the camera moves around it soon becomes obvious that there is not a soul in the house or in the garden. These are the ghosts of a joy that have long since passed. Clothes are laid out on the bed, hairbrushes are laid-out for use and there’s an old scrapbook of newspaper cuttings left open on a bedroom table. As the eerie, echoey laughter subsides, a gramophone starts playing a melancholy tune: “Gone is the romance that was so divine. ’tis broken and cannot be mended. You must go your way, And I must go mine. But now that our love dreams have ended.” ‘What will they do when their love dreams have ended?’, asks the crooner. The answer seems rather obvious: that’s when the nightmares begin.

In his youth Scott and his father had been big fans of Edgar Allen Poe whose 1843 yarn, the Tell Tale Heart tells the story of a man compelled to commit cold-blooded murder as a result of his manic obsession with the “pale blue vulture eye” of an old man: “I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye forever”. A lover of the strange and the mysterious, Scott had found himself producing the Twilight Zone some 35 years ahead of Rod Sterling.

When Wilson looks up at the giant billboard with a mixture of fear and awe, he imagines it to be the all-seeing eyes of God. Others over the years have equated it with the intrusive paranoia of the American Protective League or New York’s Watch and Ward Societies, censoring books and uncovering vice. Whatever its true significance, Scott’s editor was delighted with the finished result: “In the eyes of Dr Eckleburg various readers will see different significances; but their presence gives a superb touch to the whole thing: great, unblinking eyes, expressionless, looking down on the whole human scene. ” [8] Scott’s publishers were right: everybody would have their own idea about what these eyes meant but it is images like these, supported as they are by a flurry of furtive whispers about Gatsby’s shady, ambiguous past that made the novel more than mysterious, it made it magnificent.

Special thanks to Dirk Soulis of Soulis Auctions for information on the Esslinger Trade Sign

* Some scholars believe that Scott had been inspired by the novel’s dust-jacket that Scribner had prepared some months ahead of its publication. The evidence for this is thin on the ground. In their defence, Scott does say he had seen the art-work and written it into the novel, but this is more likely to be a reference to the ‘girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs’ who he mentions at the end of Chapter IV. On August 25 1924 Scott writes to his editor Max Perkins, telling him the new novel will be finished next week. He then adds a series of REs. One of these reads: “For Christs sake don’t give anyone that jacket you’re saving for me. I’ve written it the book.” Scott next writes to Max on October 27 1924 say that he is sending (“under separate cover”) a copy of his third novel “The Great Gatsby”. Max writes back in a letter dated November 18 saying he has read it and that the novel is “a wonder”. On November 20th Max writes again saying that his image of Dr T.J. Eckleburg is a “superb touch” that will fascinate readers. This is the first time that Scribners have seen the first full draft of the completed novel.

However, Max Perkins is writing to Scott as early as April 16 1924 about the novel’s title The Great Gatsby and suggesting the possibility of getting some cover-art underway in preparation. On April 10 Scott had told Max that he had had to discard a lot of what he’d written “last summer”. The gist of the correspondence suggests that Max had the “vaguest knowledge” of the book (April 16). It is worth acknowledging that none of Cugat’s sketches of the Valley of Ashes feature a giant billboard sign with the eyes of Dr Eckleburg and there is no indication that Scott has seen any of these sketches until August 25. This would leave Scott just six or seven weeks to conceive of Dr Eckleburg and write him into the first complete draft of the novel that he sends to Max on October 27. What is more interesting perhaps, is the fact that Cugat uses the scene of the fairground, the Ferris Wheel and glimmering light referred to in the novel’s intended preface, Absolution (which featured in his first drafts but was then ditched from the final novel). Scott adapted the preface for a short-story which he published in the Mercury in June 1924. On June 5 1924 Max writes to Scott telling him he had read the story: “Read your story in the Mercury and it seemed to me very good indeed, and also different from what you had done before — it showed a more steady and complete mastery, it seemed to me.” Scott writes back to Max on June 18th 1924: “I’m glad you liked Absolution. As you know it was to have been the prologue of the novel but it interfered with the neatness of the plan.” The phrase “as you know” leaves us in little doubt that Max was at least partially aware of the novel’s content in its early stages and could have passed this on to Cugat as part of his briefing (in manuscript copy of the novel the reader encounters Dr Eckleburg and the Valley of Ashes for the first time as Nick and Gatsby make their way into New York to meet Wolfshiem. The second version with Tom also appears in the manuscript).

In all fairness, I think Cugat was working from a verbal outline of the novel at stage when it featured both the orginal preface and the novel’s heroine, Daisy Buchanan.

Endnotes

[1] The Great Gatsby, p.26

[2] Dear Scott/Dear Max; the Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, ed. Kuehl & Bryer, Scribner’s, 1971, p.76

[3] See: https://www.rawlingsopticians.co.uk/about-history.php

[4] The Boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, counties of Nassau and Suffolk, Long Island, New York, 1609-1924, Henry Isham Hazelton, Lewis historical Pub. Co. Inc, p.280

[5] https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/9790259_c-1920-hicksville-new-york-optometrist-trade-sign; https://www.soulisauctions.com/archive-2011; ‘R.A. Esslinger Registered Optometrist’, Hicksville, The Long-Islander, August 27, 1920, p.8. Trade signs like these were reasonably common in both Britain and America at the turn of the century. His son was service manager at the Curtiss-Wright Aerodrome in Rockland. In August 1925 Esslinger’s aviator son, Reinhold Jnr. hit the headlines when he and his plane buzzed the pleasure-seekers of Coney Island in his Curtiss-made biplane. The plane ended up in the water but the pilot emerged unscathed.

[6] The Great Gatsby, p.78

[7] The 30-year old Cugat had trained at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. Cugat had been working on the 1922 Metro Pictures film, Fascination starring Mae Murray. It was his job to make it absolutely authentic its portrayal of Spanish settings. Joseph G. Robin was the skyrocket millionaire who may have provided the inspiration for Gatsby’s parties and munificence.

[8] Dear Scott/Dear Max; the Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, ed. Kuehl & Bryer, Scribner’s, 1971, pp.82-83

Other sources

The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, ed. Andrew Turnbull, Scribner, 1963, p.507

‘Absolution’, The Collected Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Penguin, 1986, pp.398-408

Filming The Great Gatsby, Bruce Bahrenburg, Berkley Publishing Corporation, 1974

Dr T.J. Eckleburg, Meaning and Symbolism

© Written and researched by Alan Sargeant, 2022