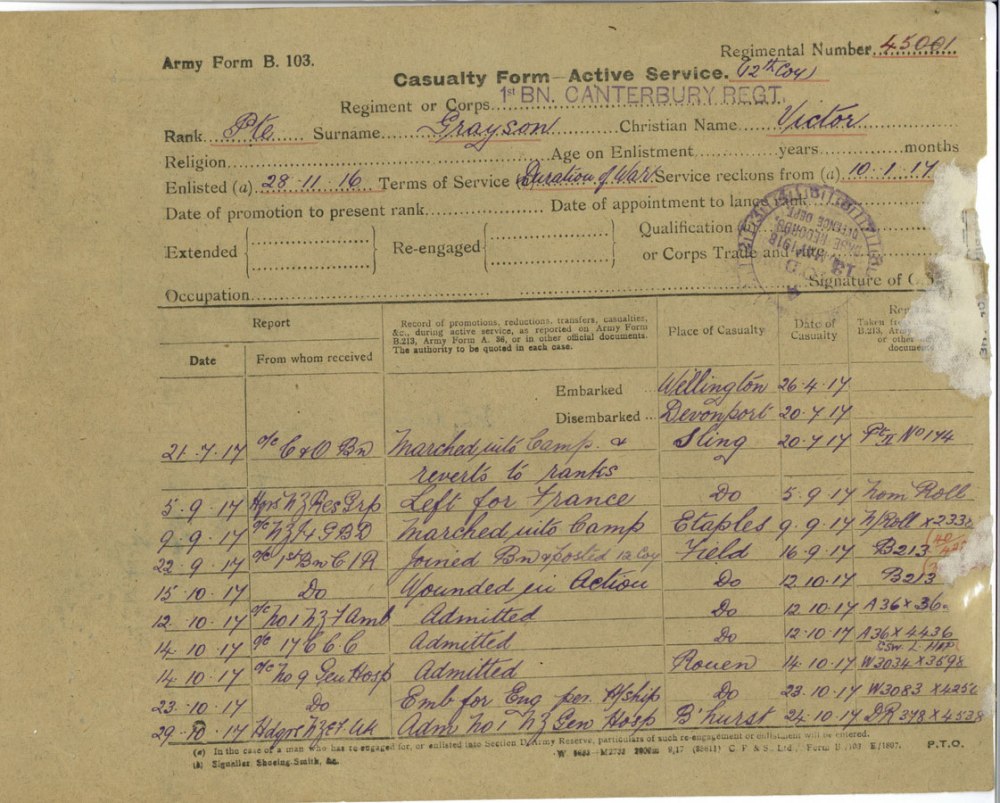

In November 1916 former Colne Valley Socialist MP and would-be revolutionary Victor Grayson enlisted with the 1st Battalion Canterbury Infantry Regiment in New Zealand. On September 9th the following year, he and his regiment arrived at Etaples Camp just as riots were taking place by New Zealand and Scottish Troops. What part if any did Grayson play in the mutiny and what was Grayson and his Manchester associate Adela Pankhurst doing in New Zealand in the first place?

One of the most curious details to emerge from a fresh look at the Etaples Mutiny of September 1917 is that notorious Socialist firebrand Victor Grayson arrived at the camp on the very day the riots kicked off. Grayson, who famously disappeared for good in 1920, had enlisted with the 1st Battalion Canterbury Infantry Regiment during a prolonged stay in New Zealand in November 1916. After basic training at Bulford Camp in Wiltshire his unit marched into the Etaples Reinforcement Camp on Sunday September 9th. It gets a glancing mention in David Clark’s biography, ‘Victor Grayson: The Man and the Mystery’ but it has never been explored in any significant detail. In fact for the most part, it’s been completely overlooked by historians on all sides of the political divide.

For mystery lovers though, the question is not: did Victor Grayson play a part in the Etaples Mutiny? The question is whether or not Special Branch, spurred on by the appointment of ‘Bolshevikfinder General’, Joseph Ball to Head of B Division at Mi5, and in light of statements previously made by Grayson in support of troop rebellion, suspected that Grayson had played a part. And if Sir Basil Thomson and Special Branch were poised to act on those suspicions, did fear of impending arrest on charges of espionage or sedition relating to this and other episodes, contribute to Grayson’s decision to vanish?

Whilst accounts differ as to the exact nature of the riots at Etaples and the politics and resentments from which they sprang, mutineer and later Communist, James Cullen is adamant that a ‘small council of action’ led by Communist agitators within the troops assumed control of the mutiny as it entered its second phase.1 What is all the more intriguing is that it was these same Anzac units that Grayson was among that led the initial assault on the ‘Red Caps’, when Arthur ‘Jock’ Healy and a dozen or so men of the New Zealand Field Artillery rushed the police cordon on the bridges preventing re-entry from the local town. The men were subsequently apprehended and beaten as ‘deserters’ by the overzealous training camp ‘Red Caps’ (WO 95/4027/5).

By 5.00pm on Sunday September 9th, a sizeable crowd had gathered around the police guardroom. One of the New Zealand Sergeants came forward and demanded the release of Gunner Healy. Members of Healy’s family insist that the beating during his arrest was fairly ‘trivial’ by Etaples standards, and that scores of other soldiers had endured the same humiliating routine, quietly, if a little grudgingly. But this time, the response was very different.

As a result of a warning by a corporal in the 27th Base Infantry Depot that the New Zealanders intended raiding the police hut, Gunner Healy had already been released by the time the mob had arrived, and the Sergeant was shown an empty cell. In spite of the foresight shown by the guards the mood of the crowd turned increasingly hostile; trouble was clearly being sought at all costs and more aggressive attempts were being made to rush the police guardroom. According to the Base Camp diary, the crowds in the vicinity of Three Arch Bridge and the Police Hut by early evening were some ‘3,000 – 4,000 strong’ (WO 95/4027/5).

As part of an effort to get to the bottom of the disturbances and stave-off further dangers, a special Board of Enquiry was set-up on the Tuesday to ‘collect evidence as to occurrences’ on the 9th. And inevitably, among the senior ranks, suspicion began to fall on agent provocateurs. In the eyes of military top brass, this wasn’t a spontaneous grassroots uprising, but an organized anti-war protest backed by German money.

In an entry dated September 12th Field Marshal General Haig notes in his diary that “men with revolutionary ideas” from “new drafts” had carried “red flags and refused to obey orders.” Much the same thing was repeated in a letter published in Sylvia Pankhurst’s revolutionary newspaper, Workers Dreadnought that November:

“We are being fed like whippets … It is something hellish. The men out here are fed up with the whole bloody lot … About four weeks ago about 10,000 men had a big racket in Etaples, and they cleared the place from one end to the other, and when the General asked what was wrong, they said they wanted the war stopped. That was never in the papers.” — Workers Dreadnought, November 3rd 1917 from an unsigned letter dated September 30th 1917

The incident set in motion a violent chain of events that saw a “seething mass of infuriated Kiwis” break the ‘Canary’ cordons and rampage through the town. In the words of R.H Mottram the men here swarmed ‘in motion like an ant-hill, in sound like a hive of bees’. By 7.30pm many of the Police had fled into Etaples itself. In his diary, General Thomson notes that a crowd of about 1,000 men had tried to break into the Savigne Cafe where several Police were in hiding. A private in the 4th Gordon Highlanders told the Aberdeen Press and Journal that at least one Red Cap had sought refuge in a hut down by the railway cutting, only to be forced to find sanctuary elsewhere after being stoned from above by a gang of angry Jocks. The ‘demeanor of the crowd was so threatening’ that practically all of the Camp Police had ‘disappeared’. They were simply ‘unable to cope’ (WO 95/4027/5).

In 1927, ex-serviceman James Cullen, one of the few men charged and sentenced as a result of the mutiny, told the Glasgow Weekly Herald that the ‘Bolshevists’ among the troops had keenly aware of the incendiary atmosphere. After the first of the disturbances, large bodies of men had broken through the piquets into town where they had held ‘noisy meetings’. As a result of the meetings, a small council of action was set-up with the ringleaders ‘giving their directions by under-channels’.

One man among the small council of action described by Cullen was New Zealand gunner, Arthur Weber Todman. Todman, a headstrong Union leader back in his hometown of Wanganui, had been enlisted into the same Canterbury Regiment as Grayson, and like Grayson had found himself in the thick of the action in the Anzac Reinforcement Camp on the day of the mutiny. In an interview with Bill Allison for his book, The Monocled Mutineer, Todman describes how this small council of action had held a meeting in a camp canteen the morning of Monday the 10th. The men wanted the Military Police withdrawn immediately or they would torch the Red Cap compound. As the wooden building sat adjacent to the ammunition dump, it was decided that if Thomson failed to comply then the Canterbury troops would do a ‘two in one job’ and ‘burn the bastards out and blow up the dump at the same time’. (MM, p.94).

Shortly after these meetings a ‘seditious’ leaflet had fallen into Cullen’s hands, bluntly asking the troops ‘to ground arms and stop the war’. ‘Let them fight their own bloody war’ it bayed. Resentments, which had been brewing for the best part of 12 months, were now at ‘fever pitch’. ‘All it wanted’, Cullen explains, ‘was a spark to cause a first rate explosion.’ 2 That spark came ‘when a corporal in the military police stationed at Etaples shot a Gordon Highlander.’ Cullen goes on to describe the event as being ‘the signal for a general outbreak by extremists’ (Glasgow Weekly Herald, February 1927).

The man shot was William.B Wood of the 4th Gordon Highlanders (No.240120), born in Pitsligo, Aberdeenshire to parents John and Rebecca Wood. He was shot in the head and died shortly after admission to hospital. A French woman standing in the Rue de Huguet was also hit by a bullet. The man doing all the shooting was Private Harry Reeve (No.204122), recently seconded to the Camp Police from the 10th Middlesex Regiment, and a champion boxer of the early 19th Century (WO 95/4027/5). His manager was Dan Sullivan, small-time boxing promoter and bookmaker deeply embroiled in the murky East End underworld, and working at this time for Bella and Dick Burge at The Ring at Blackfriars.

In the chaos that ensued, it appears that Reeve had snatched a gun from one of the New Zealanders, firing randomly above the heads of the crowd as the ‘seething mass’ of furious Anzacs taunted and jeered the Police who had dared to remain by the huts.

The shooting of Corporal Wood had become the flashpoint for rebellion.

It’s a curious story to say the least, and made all the more curious still when you learn that Harry’s uncle, Charles Reeve featured in the hysterical émigré cortège that swarmed around the infamous Whitechapel murders. The first murder had taken place with yards of the family’s home at 5 Thomas Street and as a direct response, Charles and the political firebrand, George Lusk had formed the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee from the activists and social champions that made up the International Working Men’s Educational Club. At the time of the murders the club was still on Berner Street, a favoured haunt among Whitechapel’s surly Russian exiles, and which in subsequent years at least, was more than casually frequented by the militant associates of a young Victor Grayson. At this time, however, it had the more lurid reputation for being the place where the third Ripper victim, Elizabeth Stride had been found. Club steward, Louis Diemschutz had driven his cart into the yard shortly after 1.00am on September the 30th and found the poor woman with blood still pouring from her neck. As Jonathan Moses rather blithely sums up in his essay, The Texture of Politics: London’s Anarchist Clubs, 1884 – 1914 the club consequently became subject of intrigue for a popular press ‘clamouring to connect lurid violence on the continent with the more prosaic realities of Britain’s domestic life’. The census of 1881 shows the Grayson family living at 10 Sydney Street in Poplar, just a twenty-minute walk away.

Over the course of four days, some 400 military foot and mounted police arrived to restore order, and reinforcements were drafted in from the Honourable Artillery Company and the unflinching Machine Gun Corps. As the largest troop transit camp in Northern France the threat to discipline was immense. Hundreds of men within the New Zealand and Scottish units were charged with military offences, dozens of men were charged with mutiny, and one man, Jesse Short, was executed. Many others received sentences of up to 10 years imprisonment. Just as in Petrograd, it was the Police that were the target of aggressions. The Officers, like those in Russia, were treated respectfully. Accounts of the Base Camp ‘faroany’ being hunted down the steep embankments and fleeing down to the River Canche are eerily reminiscent of the scenes played out in Palace Square:

We found the riotous crowd in a street near the bridge trying to break into a house where some military, police were believed to be sheltering. A plucky Scotch colonel forced his way to the doorway and spoke to the men, promising that the guilty policeman should be punished — Manchester Guardian, February 1930

When viewed against the fast moving changes emerging in Russia as a result of the February Revolution, the disturbances at Etaples (and among Russian troops at La Courtine, led by Jean Baltais and Klavdia Vavilov) make for very unsettling reading, and inevitably, certain questions arise. The first of these is likely to be obvious to anyone who has heard of Grayson, and one that almost certainly went through the heads of Military Intelligence in the immediate aftermath of the mutiny: did Victor Grayson — generally regarded as one of the best mob orators in Europe — have any foreknowledge of the riots and if he didn’t, what part, if any, did he play in the disturbances?

In the first of his series of four articles for the Glasgow Weekly Herald in the mid-1920s, mutineer James Cullen described how the paid-Communist agitator had to know “the psychology of the mob mind” and was taught ‘how to inflame his speeches with the catchwords and phraseology calculated to appeal to the down and out.’ And if anyone should know it was Cullen. In 1905 Cullen had been among the casualties of a British Collier ship when a mutiny broke out on the ‘Nikolif’ built Russian battleship, the Kniaz Potemkin in Odessa harbour. The mutineers, who had already murdered several of its officers by throwing them overboard, seized 2000 tons of coal before scuttling their own ship in shallow waters. Cullen was one of several young British ship workers who had fled the ordeal as rebellion spread across the port, and spent the following six months in Russia. 3 It was only the intervention of the British Foreign office that got him out (FO 369/37/58, Kew).

If there is one thing that could be said without any uncertainty at all it was this; no one knew the psychology of the ‘mob mind’ better than Victor Grayson.

Just a few weeks prior to the riots Private John King, a soldier in Grayson’s Canterbury Regiment, had been executed by the firing squad for desertion. Absenteeism was nothing new and was usually met with nothing more serious than a week confined to barracks, but frequent and sustained desertion was something else, and the response, more often than not, was swift and brutal. There was also a parallel saga taking shape at home. Just a few months prior to Grayson enlisting, several of his Socialist associates in New Zealand, including Yorkshire ex-pat Mark Briggs and Archibald Baxter, made the headlines for refusing their conscription orders into New Zealand’s Expeditionary Force. Bundled into their regiments regardless, the treatment of the men was barbaric and carried out in full view of the troops.

Back in New Zealand, Briggs had been a senior figure within the Industrial Union of Workers at the Manawatu Flaxmill. Since 1911 the Union had become increasingly radical, supporting their affiliation with the ‘Red’ Federation of Labour – also known as the ‘Red Feds’. Adela Pankhurst, who campaigned tirelessly on Grayson’s behalf in the Colne Valley by-election of 1907, paid a visit to Briggs and the Manawatu Flaxmill in July 1916. It was just a few months after this meeting that Briggs and his associates refused their mobilization orders. By March 1917 and irrespective of their objections, Briggs and his men were escorted to barracks by force. What part Pankhurst played in their decision to refuse conscription isn’t known, but it is curious to think that such a close associate of Grayson’s had been among these men at such a critical stage in their lives.

It is also curious that Adela and her sister Sylvia Pankhurst had already come to the attention of Etaples Camp detective, Edwin T. Woodhall, who discusses his encounter with the women (and his encounter with Percy Toplis in the deserter camps around Etaples) in his 1929 book, Detective and Secret Service Days. His superior at Special Branch, Basil Thomson had also discovered that Adela and Sylvia Pankhurst had set up the People’s Russian Information Bureau on funds supplied by the Bolsheviks (Queer People, Basil Thomson p.293). And her clandestine activities weren’t confined to the First World War either. In June 1941, just one week after Germany had invaded the Soviet Union, police had searched her house and confiscated a substantial volume of Japanese propaganda. Pankhurst had planned to distribute the material at meetings organised by the pro-fascist, Australia First Movement, as part of group’s ongoing offensive at the 1942 by-elections. In spite of being hastily ejected by the party for suspected espionage, Adela and twenty other members of the AFM were deemed too great a threat to National Security. In March 1942, they were arrested, charged and interned under Section 13 of the National Security Act. On March 30th, 1942, the Evening Post ran the headline, ‘Alleged Spy Ring’, sensationally lifting the lid on ‘seized documents’ plotting the ‘assassination of prominent people.’ (Australia’s Evening Post, Volume CXXXIII Issue 75).

It was a curious set of circumstances indeed, and made all the more curious by other developments.

In July and August 1917 Adela’s mother, the celebrated Suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst and Colne Valley-cum-Manchester activist, Jessie Kenney, were part of a small delegation of Labour and Suffrage supporters dispatched to Russia to meet provisional leader, Alexander Kerensky. Pankhurst Senior had been thrilled to see the overthrow of the oppressive Tsarist regime that February, but like many had viewed the Provisional Government as vulnerable. It was a largely self-funded mission, driven by the needs of publicity and marred by excessive hubris. Pankhurst had rushed across determined to help the women of Russia organize themselves and teach them how best to use the vote. That it had been the peasant women of Russia of who had got the revolution off the ground, seems to have escaped the attention of Pankhurst, and her efforts went largely ignored. The women workers of Petrograd, desperate and hungry from months of rising food prices, had organized a protest in the Nevsky Prospect demanding an increase in rations for soldiers’ families. And the response it drew from Police was as violent as it was unprecedented. By the evening of February 23rd support for the working women drew in crowds of 90,000. Women’s Day 1917 changed the lives of Russians forever.

In October 1917, just as attempts were being made to restore order at Etaples, New Zealand objector, Mark Briggs was taken from Bulford Camp in Wiltshire to the camp in Etaples and sentenced immediately to Field Punishment 1: the ‘crucifixion’.

Was Briggs part of a two-pronged Trojan plot to cause division within the ranks of the New Zealanders? Did this account for both Adele Pankhurst and Victor Grayson arriving in New Zealand within weeks of each other, just as they had arrived within months of each other in Australia in 1915? It’s unlikely, but not impossible.

Speculation about collusion may have been overlooked as a result of Grayson’s fanatical pro-war behaviour, which was seemingly at odds with Pankhurst’s equally belligerent activity in the opposing Women’s Peace Movement. But whilst I am no expert on the vagaries of revolutionary thinking during this period, Grayson’s position and intentions may not be as straightforward as many might think.

The Lesser of Two Evils

There’s been a tendency among some writers and historians to frame Grayson’s jingoistic pro-War stance inside a treacherous and mercenary shift to populism and Conservatism; this is despite the fact that several prominent revolutionary leaders in Russia also backed the war including Alexander Kerensky (a member of the ‘Trudovik’ faction within the Socialist Revolutionary Party who played a key role in Russia’s February Revolution), Irakli Tsereteli and Georgi Plekhanov, generally considered to be the founder of Russian Marxism and one-time Lenin supporter. Even on return to Russia, Bolshevik leader, Joseph Stalin sided initially with the Reformists. To understand this, you have to remember that at the beginning of the war, Germany had set out to seize significant parts of the Russian Empire. The Septemberprogramm as it became known, had been prepared by the German chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg and it is clear that territorial expansion had been Germany’s primary motive for war (huge territories in Western Russia had already been taken, including Congress-Poland, Lithuania and parts of Courland and western Volhynia). Revolutionaries like Kerensky and Plekhanov observed that successful revolution and change was less likely under Imperial Germany and they needed to push back its not inconsiderable eastern advance. To safeguard their own revolutionary interests, a significant proportion of Menshevik (‘majority’) faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party backed a military response to the ‘Prussianism’ of the Junker — Germany’s ruling military class. The remaining Bolshevik (‘minority’) faction withheld their support for the war on the basis that it was rooted in Imperialist Capitalism. The long and short of it? Opinion on the issue of war among Socialist and Labour supporters was as divided in Russia as it was in Britain.

The message to me at least seems simple: there is absolutely no reason to assume that Grayson’s pro-war belligerence is an indication he was losing interest in Revolution, quite the opposite; the pugnacious Social Chauvinism observed by Grayson and British Socialist, Henry Hyndman is likely to have been based on the preservation of a Revolutionary ideal, and not the rejection of one.

Revolutionaries like Plekhanov believed that German victory could be disastrous for the world’s proletariat. Siding with the bourgeoisie on the issue of defence was simply the lesser of two evils. Grayson might have had another reason for backing conscription; in Russia conscription and desertion among the country’s ‘peasant army’ had undermined the country’s war effort on several fronts, making the conditions ripe for revolution. There were food shortages in the towns due to the diminished labour force in the countryside (skilled and non-skilled men were in the army), and military transport and provisions congested the railway networks. These factors led to a rise in food prices which meant growing hardship for the workers, and inevitably this led to strikes. It may come as no surprise to learn that in the autumn of 1916 Grayson was reassuring his Socialist comrades in New Zealand that conscription, whilst unfavourable, would at least train men in the use of munitions and prepare them for the revolution that would almost certainly follow the war. Just weeks before, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin had similarly written that ‘an oppressed class which does not strive to learn to use arms, to acquire arms, only deserves to be treated like slaves’. If men were to be given a gun, they must ‘take it and learn the military art properly’ so they could fight the bourgeoisie of their own country (The Military Programme of the Proletarian Revolution: II, September 1916). Men, Lenin went on, must ‘set to work to organize, organize, organize’. Grayson expressed much the same sentiment in a speech he made to the Wellington Social Democratic Party that same September:

The men who have reaped the experiences of the trenches would come back trained to use guns and bayonets, and to act unitedly, and they would never again be satisfied with the old life of unemployment and want and hardship. They would make demands upon their governments … and knowing the value of organization they would be in a position to enforce their demands — Victor Grayson speaking to the Wellington Social Democratic Party, Maoriland Worker, Volume 7, Issue 293, 27 September 1916

It was not an isolated statement by any means. In September 1907, Victor Grayson had dangled a similar revolutionary carrot in Wigan. In a monologue that drew as much in the way of gasps as it did applause, Grayson told the crowd of Independent Labour Party members gathered at the Co-op Assembly Hall on Dorning Street, that he was looking forward to the time when the ordinary British soldier would ’emulate his brother of the National Guard of France, and when asked to turn his rifle on the people who are fighting for their rights’, would turn his rifle ‘in the other direction’. Grayson had no gripe with the Soldier. He was just another ‘poor wage slave who does his work for a shilling a day’. The ‘propaganda work’ that he and his comrades and carried out in the armed forces, Grayson continued, was ‘making Socialists there by the dozen’. Grayson had made no bones about the fact that when the ‘parlimentary game’ had been exhausted they would need ‘something unconstitutional to agitate the ponderous brains’ of British bureaucracy.

Grayson makes one thing abundantly clear: as far as the present war was concerned he was patriotic, but like his comrades Plekhanov and Tsereteli in Russia he felt the workers movement would have more opportunity to flourish under the allies than under ‘Prusso-German’ rule. Flooding the ranks with a readymade Socialist division would simply accelerate the process of any post-war coup d’etat.

In the words of one Tracy Chapman, Vic was still talkin’ ’bout a revolution. As he told the Wellington Social Democratic Party just one week previously: the workers had ‘the means and remedy in their own hands – organisation’. Whatever they did they must ‘organise, organise, organise.’ (Labour and the War, Evening Post, Volume XCII, Issue 70, 20 September 1916). His words were unususally prescient. Just months after making this speech, the mutinies that swept through the ranks of Russia’s Volynski and Pavlovski regiments played a decisive role its February Revolution, when significant numbers of the troops not only refused to fire on the rioting crowds, but turned their rifles instead on Police.

Several years before, in October 1909 Grayson had addressed 8,000 social democrats who had gathered in Trafalgar Square and made a ‘violent speech’ denouncing the execution of Catalan anarchist, Francesc Ferrer. According to the press, Grayson ‘advocated a life for a life’ before declaring that even if ‘the heads of every King in Europe were torn from their trunks tomorrow it would not pay half the price of Ferrer’s life’. (Star, Issue 9676, 19 October 1909). Attending that same demonstration was Naomi Ploschansky, James Dick and Fred Bower, a ‘Liverpool agitator comrade’ from Grayson’s early days in Liverpool.

Under the direction and inspiration of Ferrer, Dick and Bower had helped set up the Anarchist Communist Sunday School in Liverpool. Ploschansky set-up a sister school on Jubilee Street in the Whitechapel district of London (a venue used by Lenin, Trotsky and the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party just a few years previously). In 1909, just 12 months after its conception, the Liverpool school was moved to Beaumont Street in Toxteth, just minutes around the corner from Grayson’s mother on Northbrook Street. Ploschansky and his father returned to Russia in 1917 in time for the October Revolution.

Bower is an interesting character. Born in Boston but raised in Liverpool, the colourful ‘anarcho-syndicalist’ claims he campaigned on Grayson’s behalf in the final week of the Colne Valley by-election of 1907. In his 1936 autobiography, Rolling Stonemason, Bower describes meeting his “old towny” and having many “happy chats” that week. He also claims he was the first to inform the Pankhursts of Victor’s astonishing triumph at the polls. A red handkerchief was waved from an upstairs window in a house in Slaithwaite. It was the signal that they had won. Bower dashed around the corner to the four Pankhurst women who were waiting in a nearby car. According to Bower, the Pankhursts had “worked like Trojans” for the candidate for the full duration of the campaign. “It was a great day”, writes Bower, “and the hills resounded with the Red Flag”.

Bower was to meet Adela Pankhurst again when he visited Sydney shortly after the war. It was through Pankhurst that he was introduced to Bolshevik Consul, Peter Simonoff — Trotsky and Lenin’s newly appointed representative in Australia. Between 1918 and 1919 Simonoff had been observed entering the house of Ronald Graham Gordon, a member of several local patriot groups but later arrested as a German spy. Gordon, who claimed to have been born in Inverness in 1879, had been in the employment of Carl Frederick Muller, executed some years earlier for spying in Britain. It’s an extraordinary tale in itself, featuring deceptions as implausible as a secret printing press hidden inside an old piano, and mysterious war-time errands for Lord Kitchener. Gordon was deported to Germany but reappears in England in the mid-1930s teaching German to officers at Special Branch. In 1940 he was detained at Her Majesty’s Pleasure under Defence Regulation 18b under ‘hostile associations” and possible affiliation with Oswald Mosely’s British Union of Fascists. He was released in 1944 (see records HO 283/39 and also HO 45/25734 of the National Archives).

Fred Bower also claims to have been present at the murder of Australian MP, Percy Brookfield in March 1921. An old friend of Grayson and Bower’s days in Liverpool, Brookfield had become a confidant and friend of Consul Simonoff. Although Official Police Reports cite no political motivation behind the murder, Bower claims the killer, Russian émigré, Koorman Tomayoff had pictures of Lenin, Trotsky and Brookfield in his room. Simonoff subsequently married a New Zealander. In 1914 Bower told British reporters that he and not Tom Mann wrote the infamous, ‘Don’t Shoot: An Open Letter To British Soldiers’ pamphlet encouraging British troops to mutiny. Mann had been jailed in 1912 but released after seven weeks of public pressure. When Mann left for South Africa both Bower and Grayson were with him at the station when his train left Waterloo for the boat train to Southampton. According to Mann’s memoirs, there is some indication that Victor Grayson was very nearly arrested alongside Tom Mann (Tom Mann’s Memoirs, MacGibbon & Kee, 1967)

The Trafalgar demonstration wasn’t the only time Grayson showed he was prepared to endorse the use of violence either. Shortly after his election to Parliament he told striking dock workers in Belfast that if they were attacked by soldiers or police they had every right to fight back using any means possible, including ‘broken bottles’. His old Labour associate from Liverpool, Jim Larkin, now leader of the Belfast Dockers Union, had managed to persuade 600 of the 1000-strong Royal Irish Constabulary to mutiny in support of the workers. Like Glasgow’s John Maclean, the revolutionary Socialist subsequently appointed by Bolshevik Consul in Scotland, Grayson had been invited to Belfast to witness first-hand the challenges faced by the striking workers. On his arrival in Belfast on August 8th, Larkin accompanied Grayson around streets ‘possessed by military’ looking for a few ‘bones to split’. Grayson told the Sheffield Daily Telegraph that at every street corner a ‘gang of them with fixed bayonets’ waited eagerly for the signal to charge.’ He had gone to some of the poorest areas of the city and saw the ‘wretched people huddled together’. Later in the evening Grayson addressed a meeting of carters and dockers, and laid down a challenge; either the military withdrew or the workers would be forced to ‘do their duty’ and respond. And according to the Londonderry Sentinel he ‘did not care how soon one side or the other made a start’.

A few days later on August 11th, within hours of Grayson of declaring that if the workers ‘had not the shrapnel to shoot, they had broken bottles to throw’, those same British troops shot dead two of the rioters and injured scores of others as the panicking authorities imposed in a state of martial law.

If Grayson could incite striking workers to sedition he’d have no trouble in inciting troops if the situation arose and the booze took its usual unruly hold of his judgement.4

But could replicating the social conditions in which revolution took root in Russia engender the same kind of change in Britain? I’m not so sure. Equipping men with guns and training them in combat may have changed the shape and scale of organized crime in the UK and US dramatically (especially when paired with prohibition), but there was little hope of it ever transforming your average milkman into a dangerous revolutionary. And if Victor Grayson thought it would, then his one-bottle-of-whisky-a-day drinking habit had clearly got the better of him.

If spite of Lenin’s opinion that the working class people of Great Britain were to ignorant and too disorganized for revolution, Special Branch took a more cautious view. In his 1922 book, Queer People, Sir Basil Thomson writes:

Bolshevism has been described as an infectious disease rather than a political creed a disease which spreads like a cancer, eating away the tissue of society until the whole mass disintegrates and falls into corruption … I noticed the same symptoms in a young policeman who was shouting, ‘Let’s have a revolution !’ during the police strike.

Thomson is only too aware of what a surfeit of ‘Bolshevik oratory’ and ‘bad alcohol’ can lead to, and it’s worth noting that on Grayson’s return from Etaples in January 1918, Thomson is believed to have tasked Maudy Gregory, an associate of Grayson, to keep a watchful eye on his movements. Victor Grayson, according to Thomson, was a ‘dangerous Communist revolutionary’ who would, before too long, either link up ‘with the Sinn Feiners or the Reds’.

Disturbances among New Zealand troops carried on well into 1920, when many of the men still at Bulford (known to New Zealand Army as the Anzac Camp and unofficially as ‘Sling’) felt they should be going home. 14 of the New Zealand conscientious objectors, including Mark Briggs and Archibald Baxter, had been housed at this camp and in 1919 significant numbers of the 4,600 of the New Zealand troops still awaiting demobilization at Sling Camp rioted. That so-called ‘Monocled Mutineer’, Percy Toplis turned up at the camp that same year could only ever only add to the intrigue, and the myths.

Grayson, Bottomley & A Mutiny That Never Was

Personally I’m not committing myself to any one theory. Some writers claim that Victor Grayson was working for British Intelligence and others that he was working for the Soviets or the Irish Secret Service. He may well have been working for all three of them but as long as police and security records on Grayson remain closed we are unlikely to know either way. He was a deeply secretive man and remained a mystery to many of his friends even in his own lifetime. That Grayson disappears within a month of Toplis being ambushed and killed in Penrith in 1920 grabbed my attention certainly, but it’s not proof they ever met, or that Toplis took part in the mutiny. That said, one of the most frequent visitors to Grayson’s house in the months before he vanished was Horatio Bottomley. And therein lies another tale.

Bottomley was the editor of John Bull and highly regarded as ‘Soldiers’ Friend’ and Bottomley, for what it’s worth, was in Etaples when the rioting broke out (he had campaigned for better conditions for troops throughout the war). John Fairley and Bill Allision, authors of The Monocled Mutineer go one further than this. They allege that Bottomley negotiated with camp officials on behalf of the troops when demands for camp improvements were served to Brigadier Thomson. It is a claim backed up by Etaples witness, A.B Newland Senior who says that Bottomley ‘took an active part in persuading the men to return to duty’. Whether he was given “complete control of the situation”, as some early rumours allege, isn’t known. The writers also allege the demands for camp improvements were served by Toplis himself. The diary of General Haig shows that Bottomley was in Etaples at the time and he had dinner with him on the 12th September to discuss the morale of the troops. Just 12 months after Grayson disappeared Bottomley was charged with War Bond fraud, spent 10 years in prison and died a penniless man in London 5.

On March 6th 1922, just two days before Bottomley was brought to Bow Street Police Court and charged, a letter by A.B Newland was printed in New Zealand’s Otago Daily Times. As a volunteer with the Church Army, Newland had witnessed the mutiny first-hand and asked why Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Stewart of the 1st Canterbury Infantry Regiment had failed to mention the mutiny in his official history of the New Zealand War effort that had been published that same year. The author of the letter even claimed to have a copy of the execution orders for Jesse Short, an event that was not confirmed officially by the MOD until the 1980s [ read letter ]. As it turns out, the author of the official history, Hugh Stewart, was Grayson’s commanding officer and had spent the years immediately prior to the war in Russia. [1] Newland’s claims were corroborated in a separate account in the Manchester Guardian dated February 1930. The Guardian article starts with an incendiary quote from war poet, R.H Mottram, whose book Three Personal Records of War had been published just weeks before:

The culmination of this period was that occurrence, chiefly disgraceful to writers about the war who appear to be in conspiracy to conceal it, the Mutiny at Etaples. All countries engaged in the war had periods of widespread mutiny, a fact which should be noticed and recorded, not hushed up … With the British it occurred … over some rumoured disagreement with the police. I never knew the truth and perhaps no one knows it — The Mutiny at Etaples: An Incident of 1917 Fighting Soldiers and Red Caps, Manchester Guardian, February 13 1930.

On the surface of things. it all looks a little suspicious; Etaples Camp Commander, General Thomson is removed from the base just a few weeks after the mutiny and is retired shortly after the armistice, suspected Mutineer, Percy Francis Toplis is gunned down in June 1920, Grayson disappears in September 1920 and Etaples ‘champion’, Horatio Bottomley is jailed little more than a year or so later. In the words of R.H Mottram the world did seem united ‘in a conspiracy to conceal it’. And the mysteries didn’t end there.

In 1970 journalist and former Naval Intelligence Officer, Donald McCormick unveiled a new witness in the Grayson mystery. The man was painter and naturalist, George Flemwell. On a rare visit to London from his new base in Switzerland, Flemwell claims to have seen his old friend, Victor Grayson on a motorized canoe on the Thames, some three days after his disappearance. According to Flemwell, Grayson was on his way to Ditton Island, a pedestrianized community at the centre of the river. Flemwell claims the boat had landed alongside a jetty belonging to Vanity Fair, a wonderfully decadent riverside bungalow owned by honours tout and bagman, Maundy Gregory. But this wasn’t the last time that Flemwell would appear in a McCormick mystery.

In his 1979 book, The British Connection: Russia’s Manipulation of British Individuals and Institutions, published under McCormick’s pseudonym, Richard Deacon, the same George Flemwell appears in a coded diary alleged to have been written by Arthur Cecil Pigou, suspected ‘Master Spy’ in the mysterious Cambridge Spy Ring. The quote from the diary reads: “Established communications with Piatnitsky via George Flemwell in Switzerland: this is permanent link by Verlet in Geneva.” Osip Piatnitsky was one of the Russian revolutionaries who attended the 5th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in London alongside Stalin and Lenin. Some 12-months after these talks were held, the venue that hosted the congress came under the supervision Reverend F.R Swan, one of the most trusted and committed campaigners in Grayson’s 1907 Colne Valley by-election.

The other loose-end relates to Grayson’s former commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Stewart of the 2nd Battalion Canterbury Regiment. Between the years 1908 and 1910, the Aberdeenshire-born Stewart had found himself lecturing in Russia. His association with Professor Tadeusz Stefan Zieliński at the University of St. Petersburg had stirred within him a craving to explore provincial Russia. Stewart, who had obtained at first in Classics at Cambridge in 1907, later described how every Englishman who went into Russia ‘felt the fascination of the country’. He saw them as the ‘Athenians of the modern world’ who possessed a ‘spiritual temperament’ totally at odds with the ‘deadness of modern Germany’.

During the ‘roughness of an unknown journey’ across its sprawling peasant wilderness, Stewart had discovered that the ‘poor, backward, ill-educated drunken’ stereotype was nothing more than a myth; Russia ‘had a soul’. Over the course of his immense travels he came to learn its language and its customs. His book recording his journey, ‘Provincial Russia’ was published in 1909 by A & C Black. His co-author, Sunday Times correspondent, George Dobson was subsequently arrested by the Cheka (Soviet secret police) on suspicion of spying for the British. The fact that Stewart enrolled at Cambridge University during the initial phase of ‘Fourth Man’ Pigou’s 60-year tenure there, may be little more than a coincidence, but the passion that both men shared for the Cambridge Mountaineering Society, the Swiss Alps and economics during those critical interwar years, makes it a tantalising proposition all the same. According to his biographer, Ernest Weekley, Stewart had remained in contact with the friends he’d made in Russia right up until his death, and one of his closest was Lydia Paschkoff, intrepid explorer, ardent feminist and confidant of Russian-German aristocrat, Madame Helena Blavatsky, suspected by the British in India of being a deeply resourceful, and dangerously charismatic spy.6

In 1934, on a roundtrip back from New Zealand, the 50 year old Stewart fell ill and died. He had set-off from Auckland on the cruise ship, the R.M.S Akaroa on September 14th and had fallen ill some three days later. An anonymous letter passed to the press from a fellow passenger had claimed his initial illness had not been serious. Reports of the time go on to describe Stewart as a man of ‘splendid physique’ who had left New Zealand ‘in apparently in the best of health’. The ship and its passengers had arrived at Pitcairn Island — home to the most famous mutiny of all, the Mutiny on the Bounty — when things took a turn for the worse. Within 10 days of being confined to his cabin Stewart was dead. Why he was buried at sea and not on Pitcairn Island is anyone’s guess, but needless to say it’s another deeply frustrating puzzle in an ever frustrating mystery.

What Became of Victor Grayson: The Irish Theory

What happened to Victor Grayson? Among the handful of plausible theories that have been put forward over the years, there could be a strong case for arguing that Grayson never made it out of Liverpool during that last week of September 1920, despite the best efforts of former Intelligence man, Donald McCormick to shuttle him back to London, and the combined creativity of Cocks, Hunter and Beckett to resurrect him mind, body and spirit-measure, during some post-meeting pub crawl in Maidstone in 1924. As far as the Police (and his mother) were concerned Grayson was last seen addressing a meeting in Liverpool in the last days of September 1920. He was scheduled to pay a visit to Hull but there is no indication that he ever arrived there. Victor’s brother William told the Daily Herald in March 1927 that he “left the hotel in which he was staying and never returned for his clothes”. An insurance policy on his life remain unclaimed.

And that’s as much as we know for sure.

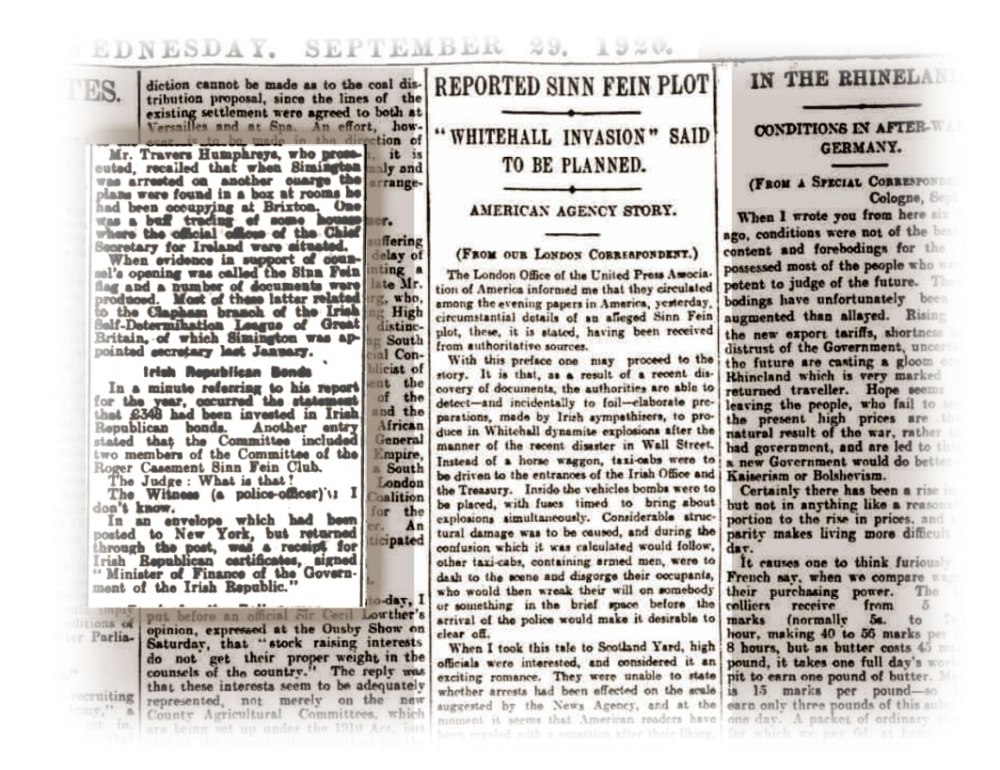

But it’s here that the story takes on an additional twist. On the very day that Grayson disappeared, another curious story reached Britain from New York. The story centred around a major terror attack that was due to take place on British soil. The target was Whitehall, and it was being hatched by a British-based group loyal to Sinn Fein. The London Office of the United Press Association of America began circulating a story that the discovery of documents by US & UK Intelligence had resulted in the detection and the foiling of preparations to detonate explosives at the entrances of the Irish Office and the Treasury in London. After the explosions it was anticipated that armed men would burst from stolen taxi-cabs parked in the neighbouring streets and attack at random the passersby thrashing around in the ensuing panic. It was already believed that munitions and incendiary devices had been secreted by Sinn Fein in London and that attacks involving ‘well known individuals’ were taking shape (Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer 29 September 1920).

According to the press, hundreds of people were rumoured to be involved and several arrests had been made.

Whilst Scotland Yard were quick to dismiss it as an ‘exciting romance’, within weeks of the story being leaked, Michael O’ Kelly Simington, a clerk at the Office of Works, was tried for wrongfully retaining plans contrary to the Official Secrets Act. A search of his home in Brixton had uncovered rifles and hordes of pamphlets and letters poised for immediate distribution. As Secretary of the Clapham Branch of the Irish Self Determination League it is believed that Simington had been plotting an attack on the offices of Hamar Greenwood, at this time Chief Secretary for Ireland. The clerk had been arrested on September 26th, just days before the story of the Whitehall attack hit the press, and little more than 48 hours before Grayson disappeared. Inspector Percy Hallet of Scotland Yard found a book in Simington’s possession containing a list of the London branches of the Irish Self Determination League, a receipt signed by the Minister of Ireland’s Revolutionary Republic plus a statement that the plotters included at least two members of the Roger Casement Sinn Fein Club.

Casement was a man full of secrets and contradictions: poet, humanitarian, diplomat, revolutionary and tragically for him at least, a suspected homosexual. Crucial to his conviction — both as a homosexual and a traitor — were the so-called Casement Diaries. Just as MPs in the House of Commons were being presented with a petition demanding clemency for Casement, extracts from these diaries were widely circulated amongst the press and along the corridors and chambers at Whitehall. The explicit references to sodomy served to weaken support for Casement during the last critical moments of his appeal, and it was the timely revelation of these diaries that Victor Grayson is said to have been investigating in the weeks and months before he vanished. Grayson believed the diaries to be a forgery. And it was Maundy Gregory, the man tasked with watching Grayson, who Grayson suspected of having forged them.

One does not like to speak ill of the dead, but the truth about (Casement) ought to be published so that the Irish should not regard him as a martyr. The present writer has seen extracts from his diary, and nothing so filthy, so pornographic, so infinitely disgusting as what Casement set down in black and white can be imagined … I am writing thus strongly because I am aware of the tremendous efforts made to get Casement off — ‘Club Window Goissip’, Sheffield Evening Telegraph 05 August 1916

We have already seen that that shortly after Grayson’s return to England from Passchendaele, Sir Basil Thomson, the Director of Special Intelligence at Scotland Yard, and the man now widely credited with ‘discovering’ the Casement diaries, told Gregory, a known intelligence gatherer, that Victor Grayson was a “dangerous Communist revolutionary” who would either link up with “the Sinn Feiners or the Reds”. It was an unusual statement to make given the years of political inactivity that now characterized the wounded Grayson, but amongst biographers and mystery writers it is now commonly believed that Gregory agreed to keep an eye on him.

That the Whitehall Plot should coincide with Grayson’s disappearance and that it should be organized, at least in part, by members of the London-based Roger Casement Sinn Fein Club adds a compelling new line of enquiry.

Simington and the Irish Self Determination League had two main offices outside London: one in Manchester under the auspices of Thomas Faughan in Whalley Range, and one in Liverpool by Patrick J. Kelly. The context, geographically at least, couldn’t have been more apt: Liverpool was the hometown of Victor Grayson and Manchester, the mother of his political invention. Both cities fared badly in the immediate aftermath of the so-called Whitehall plot. Liverpool endured the worst of it with “18 simultaneous fires” breaking out across the city in one blistering night of carnage alone (Western Daily Press, 29th November 1920). Simington had been arrested on September 26th and by October 21st 1920 he was being sentenced to 15-months hard labour. But the story didn’t end there. Within days of Simington’s conviction documents were being leaked to the London Evening Standard citing evidence of an alleged plot to burn England to the ground by vengeful Sinn Feiners. Details of a “campaign of outrage and incendiarism” leapt as sensationally as the flames themselves from the various newstands across Britain. Warehouses throughout Liverpool, Bootle and Manchester were sought and routinely torched, with tins of petrol or paraffin found outside the warehouse doors. In one episode a youth was shot by an assailant making a getaway and in another a bolt-cutter was used on a Policeman (Western Times, November 30th 1920). Naturally, the press stories possessed all the fast and furious extravagance of your class crime caper, with tales of ‘long-running gun battles’ between arsonists and police. Those who stood trial included Neil Kerr, aged 57, Henry Peter Coyle, aged 25, Matthew Fowler, aged 28, Patrick MacPartlin aged 30, James McCaughhey, aged 32, Sheila Brown, aged 30 and Kathleen Brown, aged 24 (Birmingham Daily Gazette 08 February 1921). The two sisters arrested were teachers and organized the Liverpool branch of the Roger Casement Sinn Fein Club on Bridge Road, in Seaforth, just south of the city. They weren’t the only well-educated and self-possessed women in the group. In 1918, 34-year old teacher Roisin ni Chillin (Maria Rosina Killen in the press) moved from Manchester to London where she became secretary of the Casement Club in Brixton, earning £340 a year working at the Fairclough Street in Whitechapel (Letters from Roisin ni Chillin to John O’Brien July 1920, Feb 1921). In October 1923 Killen’s relationship with ex-British soldier and trainee teacher, Reginald Dunne, convicted of the murder of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson in London the previous year, was investigated by Police. His accomplice was Joe O’ Sullivan, Michael Simington’s co-worker at the Ministry of Labour (Sheffield Daily Telegraph 19 July 1922). At the time of his death Wilson had been serving as Special Adviser to the Intelligence Department at Scotland Yard and there was a suggestion that a warning had been given. Despite a thorough investigation, all charges against Dunn’s Casement Club friend, Maria Rosina Killen were dropped.

Simington and the Club weren’t the only ones causing concern for Britain at this time. Running parallel to this saga was a threat with more far-reaching consequences. Just two months prior to the arrest of Simington, Scotland Yard and the Secret Service had learned that Patrick McCartan of the as yet unrecognised Irish Republic had made clandestine trips in Moscow to negotiate a treaty between the Soviets and the Dáil Éireann. The trip had been made during the latter half of May and by September 1920, possible collusion between the Bolsheviks in Russia and ‘Feiners’ in the Irish Republic was looking more plausible by the day.

Irish Justice Minister, Denis Henry hastily prepared a government white paper on the threat that such a treaty would pose to Britain. The white paper featured a copy of a memorandum signed by the Irish Republic’s Minister of Propaganda, Desmond FitzGerald (see: Intercourse Between Bolshevism and Sinn Fein, Parliamentary Papers, Session 1921, Vol. XXIX, p.489). Russia was the only country in the world at this time that had formally recognized the Irish Republic. More significantly for Victor, it was his old Liverpool and Belfast comrade, Jim Larkin who presented the most imminent danger.

In September 1920, the indomitable Belfast strike leader was serving time in a New York prison for acts of ‘criminal anarchy’ but it was feared that Larkin’s extensive militant network may have played a role in one of the dealiest peacetime attacks on American soil. The Wall Street Bombing was carried out on September 16th 1920., just twelve days before Grayson went missing. A horse-drawn wagon had been parked across the road from the headquarters of the JP Morgan bank, and at noon over 100 lbs of dynamite and 500 lbs of iron tore through the air. There were close to 50 fatalities, hundreds of injuries and more than two million pounds worth of damage had been inflicted on neighbouring buildings. During his time in the US the Irish Labour Leader had joined the Socialist Party of America. He was subsequently expelled from the party for contact with the Soviets. His arrest on November 9th 1919, had coincided with raids on the New York headquarters of the Russian Soviet (Leeds Mercury 10 November 1919).

The day prior to the Wall Street bombing, Larkin had made an appeal through the Larkin Defence Committee demanding the release of Terence MacSwiney, at this time on hunger strike in Brixton Prison (Daily Herald 15 September 1920). His New York-based brother Peter MacSwiney was closely aligned with the Roger Casement Sinn Fein Club and it’s interesting to note that Casement’s sister Agnes, an associate of the Club’s founder Arthur Griffith, was also living in New York at this time. The fate of MacSwiney had been the trigger for Simington’s Whitehall Plot in the first place and MacSwiney’s eventual death a month or so later, 74 days after he had started his hunger strike, was ostensibly the motive behind the decision to torch the North. MacSwiney died on October 25th, and by November 29th, Liverpool was burning.

Having already united large sections of the Irish Labour Movement and the Irish Volunteers of the 1916 Easter rebellion, nervous Conservatives believed that Larkin’s role in preparing the groundwork for the Soviet-Irish alliance was already quite substantial. They also feared that as a consequence of this success, Larkin would be the natural go-to candidate for the Soviets, who continued to have their doubts that any one leader in Ireland could unite the various revolutionary factions. That July, The Daily Mail had been even more contentious and wrote that Larkin’s “Irish Labour movement” and the Revolutionary Labour Movement “had assumed greater and greater control over the Sinn Fein insurrection.”

Whether or not Grayson had a hand in any of this, or whether he was even aware of Larkin’s plans isn’t known. Several of his closest friends, including Robert Blatchford, said Victor had taken a keen interest in Irish politics since returning from the war and was actively pursuing the Casement story. It was a statement that was supported by the IRA’s Frank Ryan in 1936.

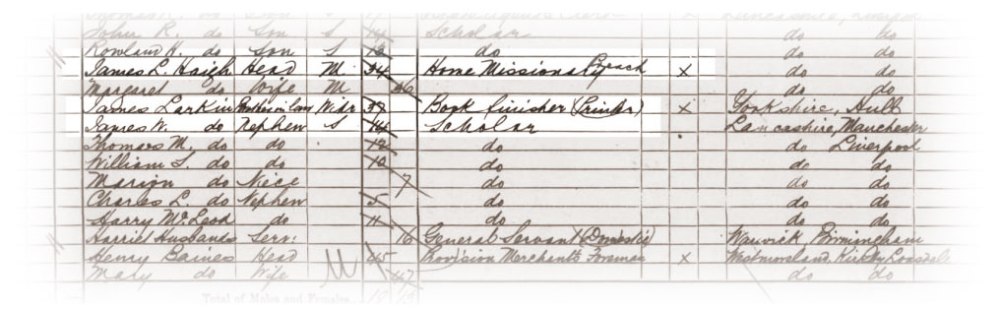

Had Grayson’s interest in Casement brought him into contact with Simington and the Roger Casement Sinn Fein Club operating in Brixton? Was it blind panic that made him bolt? Had he shared any intelligence regarding the alleged plot with Police and had this put him in an impossible and potentially perilous situation? We may never know. What we do know is that Grayson’s purported Irish sympathies can be traced all the way back to his early days in Liverpool when Grayson and his mentor, Reverend James Lockhart Haigh were assisting in the various Christian Missions on the notorious Scotland Road.

For the streets around Vauxhall and ‘Scottie Road’ the arrival of over 300,000 Irish Migrants during the late 19th Century had contributed to privation of almost biblical proportions. Many of the refugees had fused en-masse around the streets surrounding the docks, and the Missions managed by Reverend Haigh provided ballast for the poor and the needy. Haigh’s experience of Scotland Road played no small part in his debut novel, ‘Sir Galahad of the Slums’ (1907). Described by the New Age journal as a “thoughtful and suggestive experiment in Sociological fiction” there was nothing really new here. The discreet ideological connection between Knights of the Holy Grail and Marxism had been formed by Marx himself in his 1853 article, The Knight of Noble Consciousness before being belligerently re-imagined as a design for life by Comrade Lenin and as battle-plan by Stalin and Kudenko. The Bolsheviks had seen themselves as a secret military-religious order in the mould of the Templar and the Knights of the Round Table, with Lenin re-cast as the Grail Knight of the much-sought Soviet Union. In his novel, Haigh’s hero is called Vernon. His real-world counterpart was called Victor. And arguably his greatest success in life was in enrolling Victor at the Home Missionary College in Manchester, a test of character that Sir Grayson passed with ease.

Was it just a coincidence that the Reverend’s book was reviewed in Christian Socialist journal, New Age on the very day that Haigh’s flesh and blood protégé, Victor Grayson — much heralded people’s champion and devoted servitor — had his name put forward as candidate for the Colne Valley by-election? In little more than 12-months Grayson would come to be editor of New Age, so it’s reasonable to assume that the journal played a fairly priveleged role in forging his future and maintaining his initial fanbase.

In literary tradition, Galahad was the illegitimate son of Lancelot and Elaine of Corbenic and renowned for his gallantry and purity, a Knight chosen by God himself to seek the grail. Taking obvious cues from the myth, a succession of hacks and fantasists have re-cast Albert Victor Grayson as the illegitimate son and heir of the noble (and swaggeringly militaristic) Spencer-Churchill dynasty invited to sit at the Whitehall table: a rough diamond mined from the most hallowed of grounds, a nobleman by birth, but by trade, just your average fella. Many of the same myths had been built around Stalin, the classic changeling. In fairytales of this nature it always came down to just one thing: the fightback of the disinherited, the return of the repressed. It was as true of Robin Hood as it was of Moses. And if the dubious mythology of his birth didn’t swing it, the entire pitch was spelled out in his name, Victor: one who triumphs, one who defeats.

Even for those as righteously egalitarian as James Lockhart Haigh and his followers, it seems they had a hard time believing that something as powerful and precious as Grayson could ever spring from some backwater tenement in Liverpool. Base metal was base metal, gold was gold.

The story of the grail had gained fresh energy among followers of Frederick Furnivall, celebrated Christian Socialist and co-founder of the London Working Men’s College. And in contrast to what you might expect, the early Christian Socialists were not advocating democracy here but ‘community’. It was about hierarchy, not equality. Government, like holiness, emanated from the top down and true reform had to be conceived, and then enforced by an elite representing the will of the people. It is little wonder the myth resonated so deeply with the young Bolsheviks who’d sought sanctuary and deliverance in the mission halls of London’s East End during their twenty years in exile.

One of the most curious facts to emerge from my look at the life of Haigh is that between 1881 and 1907, another man by the name of James Larkin was living with Haigh and his wife Margaret at his home at 49 Mere Lane in Everton, West Derby. The man was a 37-year old book finisher. He was also the brother of Margaret. Lodging with Larkin was his 14-year son, also called James, and the boy remained in Haigh’s care until 1905 or so, several years after the death of his father. It seems inconceivable that this is the same James Larkin that Grayson befriended in Liverpool, but an Irish relation perhaps? Haigh’s mother Margaret Lockhart was from Ireland, so its certainly plausible. The age of the boy tallies with ‘Big’ Jim Larkin but this boy takes up his profession as a Nautical Engineer, not a docker or dock foreman.

It’s not the only occasion in which there is a sliver of Irish intrigue. Labour member Seymour Cocks insists he saw Grayson in Maidstone where Victor divulged his post-War activities in the Irish Secret Service. Cocks also says that Grayson handed him a Belfast address, an address that he subsequently misplaced. The strangest story by far though, comes courtesy of a woman in Leeds in August 1947. Selena Ethel Kennally of Bridle Path Square in Cross Gates told the Yorkshire Post that she was convinced the man she married as John Wilson in 1928, and who died at a Sheffield Hospital the following year was none other than Victor Grayson. Mrs Kennally said that when she first met Grayson he was working as a journalist at a newspaper but had left his job after one week of marriage. She maintained he had no identity papers and no luggage with the exception of one suitcase. According to the woman, a few days before he died ‘John’ was calling for someone called ‘Ruth’. Doctors also claimed the during his last few hours alive, the man had been repeating the name ‘Grayson’. Intriguingly, among his few possessions was Irish Republican Belt with the name “Grayson” stamped on it (Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer 16 August 1947). Armed with this information I did another a trawl of the archives. And whilst it did throw up a Selena Ethel Kennally living with her husband John (a former Police Inspector) at Cross Gates in 1939, a marriage between a John Wilson and Selena Kennally in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1928 has so far managed to elude me.

What follows in the timeline below, is a fairly informal attempt showing Victor Grayson’s political rise and development alongside the revolutionary drama unfolding in Russia, and as seen through the eyes of the Secret Service, the MiS and Special Branch, whose response to subversive behaviour, both in the trenches and at home, was often nothing short of hysterical. In fact there may be an argument for saying that the seeds of the first ‘Red Scare’ in Britain were planted during and not after the war and are concomitant with anti-German hysteria, especially in view of Vladimir Lenin’s trans-Germany transit back to Russia in time for the October Revolution. The fact that the Bolsheviks’ return to Russia had been signed-off and financed at the highest level by German Chancellor von Bethmann-Hollweg himself — and without the complete understanding of the Kaiser — could only have added to the paranoia and confusion. The infamous Scisson Documents released shortly after the mutiny in 1918 took concerns to a whole new level. The 68-page collection of ‘secret documents’ obtained by Edgar Scisson alleged that Trotsky, Lenin, and the other Bolshevik revolutionaries were agents of the German government. Fakes the documents may have been, but in some Conservative quarters at least, there was certainly no shortage of faith in them.

Timeline & related articles

The timeline is not an exhaustive account by any means and is clearly too narrow in scope for any serious analysis, but it’s hoped that it might provoke discussion at the very least. Or, as is more likely, further discussion may take Victor’s lead and simply vanish.

Grayson Timeline and Biography:

https://pixelsurgery.wordpress.com/2018/10/18/grayson-timeline/

1 The British Lion, 20, July 1927.

2 This is no idle use of the word ‘spark’. It’s probably a reference to the pharse “Из искры возгорится пламя” (“From a spark a fire will flare up”) which became the motto of the revolutionary paper, Iskra, and for many years printed in London. The line was dedicated to revolutionary martyrs, the Decembrists in prison. The martyrs, incidentally, were composed of military personnel. Were the riots staged as a tribute to previous revolutions and intended to register at a symbolic as much as practical level?

3 Glasgow shipbuilders, John Brown Shipbuilding, John Elder & Company,Beardmore, Maxim and Vickers Ltd were among a handful of British companies awarded contracts at the Black Sea Shipyard as part of a deal with the Imperial Russian Navy. Several were to provide technical assistance in the Nikolayev shipyard that Cullen mentions in his report. In his article for the Glasgow Weekly Herald Cullen mispells Nikolayev, ‘Nikolif’.

4 Grayson responded to criticism of his ‘bottle speech’ by saying that bottles had been thrown at troops before he made his remarks in Huddersfield on August 4th. In fairness, it’s a grey area and Victor subsequently admitted that he had lost no shortage of sleep over both the ambiguity of his phrasing and the timing of his remark (his remarks had been made on Sunday August 11th and that night Belfast’s striking dockers had fought back with broken bottles, but bottles had also been thrown the previous evening). As a result of the violence two unarmed Catholic supporters of the dockers (Charles Mullan and Margaret Lennon) were shot dead. Grayson’s subsequent lecture of ‘The Destiny of the Mob’ scheduled to be held at the Corn Exchange was duly refused. One of his last words on the subject was this: “there was never a strike were people were killed by broken bottles, but in Belfast, strike people were killed by bayonet and shot. People did not ask questions about the bayonet and shot.” (Gloucester Citizen 07 December 1907).

5 Curiously, Labour’s John Beckett, who claims his father lost substantial sums of money in an earlier scheme by Bottomley, says he was one of the few people who saw Victor Grayson alive shortly before he disappeared. The latter claim was made by John’s son Francis Beckett (co-author of Blair Inc) in his 2016 book, A Fascist in the Family (Routledge). In 1939 John Beckett was interned under Defence Regulation 18b for his pro-Nazi activities as part of the British Union of Fascists.

6 Lydia was also a very good friend of intrepid Swiss explorer, Isabelle Eberhardt who embarked on her own legendary fight against the empire. Isabelle’s mother, Nathalie Moerder was a Russian aristocrat and her father, Alexandre Trophimowsky was a renowned Bakunin anarchist. In addition to being an explorer, Lydia also worked as a correspondent for French newspaper, Le Figaro in St. Petersburg. Lydia married Nikolai Mikhailovitch Paschkoff, son of respected General Vasily Paschkoff, a close friend of Tsar, Alexander II. The Paschkoff family held mineral and agricultural estates later purchased by Manchester MP, Alexander Brogden and his company, The Russia Copper Company. The Paschkoff family became enormously popular among Russian peasants and were major proponents of Russian Evangelism, which subsequently became known as Paschkovism. The movement spread and links were developed with the Baptists and nonconformity groups in Britain. After the assassination of Alexander II in 1881 many Paschovite leaders were exiled in Siberia as subversives. Paschkoff’s nephew was Vladimir Chertkov, a close friend of Leo Tolstoy, who briefly sought exile at Tuckton House in Bournemouth, England. Grayson’s father in law, John Webster Nightingale, a prominent nonconformity figure himself, also lived in Bournemouth during this period. The progress of Russia had been seen as incompatible with Tsarist rule among Socialists and Capitalists alike. Social agitation began to embrace not just the revolutionary but the Conservative. Chertkov’s Tuckton House became a key location in the development of Soviet espionage networks in post-October 1917 Britain. According to historian, David Burke, visitors to the house included Peter Kropotkin, Gertrude Stedman and Jacob Peters who later became a high ranking member of Lenin’s ‘Cheka’ (security forces). Stedman’s daughter, Melita Norwood would go on to become one of the most successful Soviet agents in Britain and reported to be even more highly valued than the Cambridge Five. Manchester University’s David Briggs claims that his grandfather, Charles Lionel Briggs introduced Grayson to Chertkov (Tchertkoff) at Tuckton House were he became a tutor and mentor to Chertkov’s son, Dima. In one of his wartime letters, Briggs says of his friendship with Grayson, “We had great times together at Tuckton” (A Quiet Lion and his Battlemaid, David Briggs)

Main Sources

Victor Grayson, The Man Behind The Mystery, David Clark, 2016

Lines of communication. Etaples Base: Commandant diary WO 95/4027/5

The New Zealand Division, Otago Daily Times, Issue 18496, 6 March 1922

BBC Radio 4 – Punt PI, Series 7, The Case of the MP Who Vanished

Armageddon or Calvary: The Conscientious Objectors of New Zealand and “The Process of Their Conversion”, XV, Mark Briggs.

Echo of the War (Mutiny in Etaples), Evening Post, Volume CIX, Issue 85, 10 April 1930

Mutiny at Etaples, Lake Wakatip Mail, Issue 3948, 20 May 1930

Workers Dreadnought, 3 November 1917, letter mailed to editor, Sylvia Pankhurst

NZDF Personnel Archives

Maoriland Worker, 1909-1918

Poverty Bay Herald

The Coming Revolution – New Zealand Times, Volume XLI, Issue 9461, 22 September 1916

Londonderry Sentinel, 08 August 1907

Belfast Newsletter, 12th August 1907.

Rolling Stonemason: An Autiobiography of Fred Bower, Fred Bower, Jonathan Cape, 1936

Manawatu Times, Volume XL, Issue 13556, 21 November

New Zealand Star, Issue 12284, 5 April 1918

Evening Post, Volume XCII, Issue 70, 20 September 1916

Otago Daily Times, Issue 17319, 20 May 1918

Greymouth Evening Star, 20 May 1918

The Bottomley Case, New Zealand Herald, Volume LIX, Issue 18048, 24 March 1922

Fascist in the Family (Routledge Studies in Fascism and the Far Right), Francis Beckett, 2016

Ashburton Guardian, Volume XXXVI, Issue 8542, 31 August 1916

Ashburton Guardian, Volume XXXIII, Issue 8813, 9 March 1914

Hastings Standard, Volume IV, Issue 415, 22 July 1915

Feilding Star, Volume XIII, Issue 3138, 11 January 1917

Non-Conformist Births And Baptisms

Press, Volume LXIV, Issue 19329, 6 June 1928

World War I Almanac, David R. Woodward

Northern Advocate, 14 July 1928

Patriotic Labour in the Era of the Great War, David Swift, 2014

Industrial Peace Union of the British Empire, Adela Pankhurst Walsh, Pallamana Press (Australia)

Mutiny at Etaples, Julian Putkowski, Shot at Dawn website

Douglas Haig: Diaries and Letters 1914-1918, Gary Sheffield, John Bourne

Stalin and Lenin’s forgotten London hangouts, Daily Telegraph, Hugh Morris

Conspirator: Lenin in Exile, Helen Rappaport

Lenin in London: Memorial Places, trans. Jane Sayer

William J. Fishman, East End Jewish Radicals, 1875-1914

The untold story of the man who started the Great War mutiny, Arthur Whelan

Hugh Stewart (1884-1934): Some Memories of His Friends and Colleagues, Ernest Weekley

Churchill’s Secret Enemy, Jonathan Pile

The Spanish Farm Trilogy 1914-1918, R. H. Mottram

Petrograd 1917, Caught in the Revolution: Helen Rappaport, 2016